Introduction

For generations, Abraham Lincoln has been known as “the Great Emancipator.” His Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, effectively declared the freedom of enslaved people in most places within the Confederacy.

Lincoln abhorred slavery throughout his life. But that did not mean he always believed it was possible to abolish slavery, nor that Black people and white people were entitled to all the same rights. When Lincoln became president and the Civil War began, Lincoln had no plans to end slavery in states where it already existed. Rather, his stated goals were to stop white southerners from spreading slavery into new locales and to reunite the nation. In the fall of 1862, however, Lincoln reached the conclusion that to strengthen the U.S. war effort, he needed to use his power as president to attack slavery.

Lincoln was not unique among white Northerners in shifting his views on the relationship of slavery to the war, nor in the complex distinctions he drew on matters of slavery and race. Today, we may have trouble grasping how Lincoln could believe slavery could continue in the states where it was already entrenched while also opposing its expansion into Western territories, or how he could recognize slavery as unjust and immoral while also refusing to embrace full racial equality. Yet many white northerners shared his views.

The free states were home to a strong anti-slavery movement, and the older northern states had abolished slavery in the decades following the American Revolution. But many white northerners who opposed slavery were also quite racist. In several northern cities during the Civil War, white people formed mobs and rioted against Black people and their neighborhoods. Some feared that the end of slavery would bring an influx of African Americans to the North, flooding the labor market with new workers and thereby driving down wages, or radically reconfiguring the social and political landscape. In July 1863, six months after the Emancipation Proclamation, working-class white people in New York City rioted for five days. They voiced anger about the wartime draft and fear of job competition from slaves freed by the Proclamation. Over the course of the week, the rioters lynched eleven Black men, burned an orphanage for Black children, looted and destroyed numerous Black-owned businesses, and forced hundreds of African Americans out of the city. Many white Northerners were horrified by the events and rushed in to aid victims. The riots in New York suggest the complexity—and instability—of race relations in the free states during the war, as well as some white Northerners’ fears about the abolition of slavery. The following collection of documents explores the meanings of slavery and emancipation in the North around the time of the Civil War and develops the context for Lincoln’s own evolving positions.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- What arguments against slavery did Lincoln and others put forward? When did they make arguments on moral and philosophical grounds, such as ideas of justice and human equality? When did they make arguments on other grounds, such as economic policy or military strategy?

- What distinctions did Lincoln and other white Northerners draw between ending the institution of slavery and achieving racial equality?

- How did the goal of saving the Union expand to include ending the institution of slavery?

- What feelings and concerns did writers and artists—both white and African American—express about the consequences of emancipation? How did published images of escaped slaves reveal the varying beliefs that Northerners held about slavery and emancipation?

Mapping Slavery and Freedom

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 effectively overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by allowing U.S. citizens of Kansas and Nebraska Territories to vote on whether to permit slavery. (Citizens could vote only if they were white and male.) In authorizing slavery in a region from which it had previously been barred, the act angered many Northerners. Stephen A. Douglas, a Democratic senator from Illinois, promoted the Kansas-Nebraska Act as necessary for encouraging settlement and economic development in the region. He also argued that allowing voters to decide whether to allow slavery was an essentially democratic solution that followed the principle of popular sovereignty. Lincoln offered a powerful rebuttal to those claims in a speech delivered in Peoria, Illinois, in October 1854. He insisted that it was one thing to tolerate slavery where it already existed but quite another to allow it to advance into new territories, even if voters desired it. He said, “I particularly object to the new position which the avowed principle of this Nebraska law gives to slavery in the body politic. I object to it because it assumes that there CAN BE MORAL RIGHT in the enslaving of one man by another…The argument of ‘Necessity’ was the only argument [the founding fathers] ever admitted in favor of slavery.”

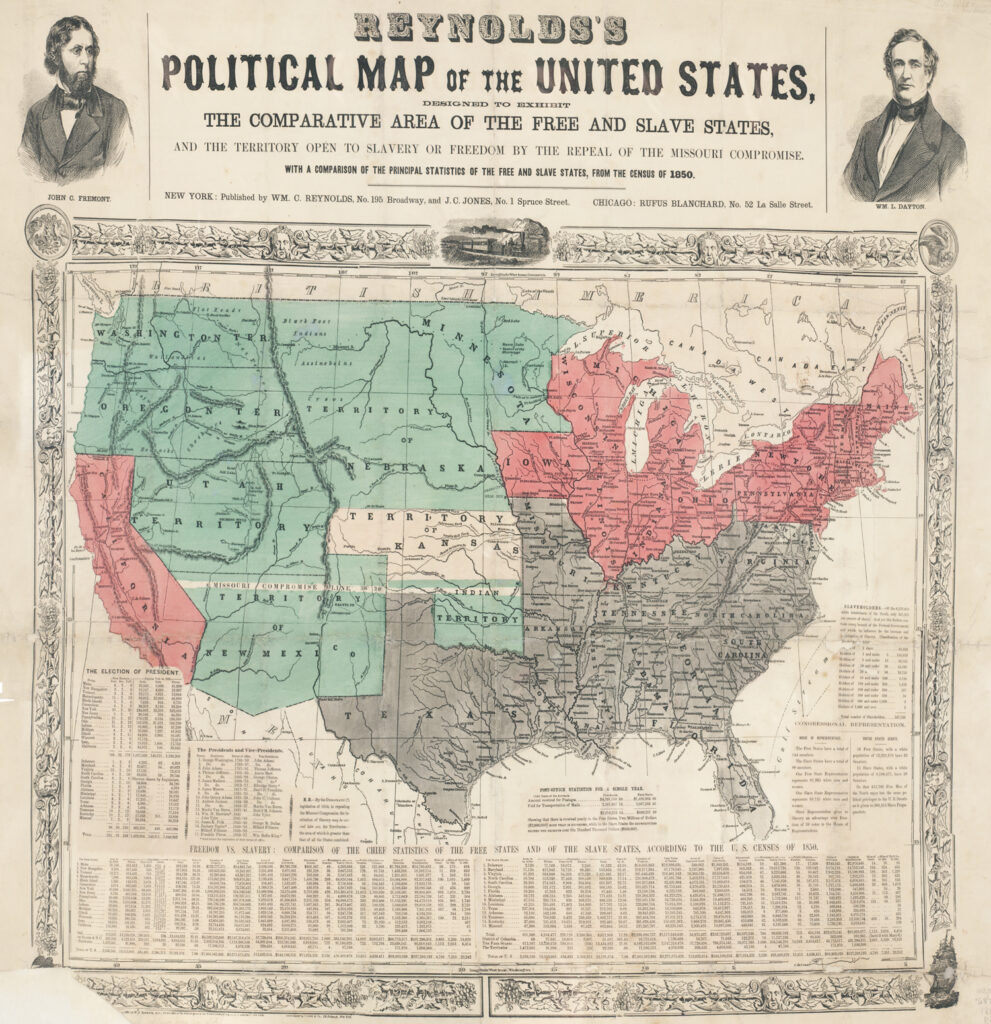

The following map was published two years later, during the presidential campaign of 1856. This election pitted Democrat James Buchanan against John Frémont of the recently formed Republican Party and against former president Millard Fillmore, who ran for the American Party, or the Know-Nothings. (Fremont ultimately carried eleven northern states but lost the election to Buchanan.) The map’s creator, William C. Reynolds, supported the Republican Party, and the map vividly illustrates the party’s condemnation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

The main part of the map portrays the United States, including the western territories, colored according to slave, free, and “open to slavery” status. The lower portion of the map provides statistical comparisons of existing slave and free states based on the 1850 census, the 1852 presidential election results, congressional representation, and the number of slaves held by owners. Some of these statistics may appear puzzling or surprising to modern readers. For example, the map informs the reader that, in free states, the U.S. Post Office operated at a profit of about two million dollars a year, while in the slave states, the post office operated at a loss of about half a million dollars per year. It also suggests that white citizens of slave states enjoyed disproportionate representation in Congress due to factors such as the Constitution’s three-fifths clause and the free states’ much higher white population density: “one Free State Representative represents 91,935 white men and women. One Slave State Representative represents 68,725 white men and women.” While slave and free states had roughly the same number of U.S. senators, the senators from free states represented a voting population approximately twice as large as those from slave states.

Questions to Consider:

- Examine the map’s graphic representation of the United States. How might this visual presentation have encouraged opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act?

- What kind of information appears in the statistics at the bottom of the map? Why do you think Reynolds included this information? What does it demonstrate about the economies of slave and free states? How do the statistics support arguments against the extension of slavery?

Lincoln’s Evolving Arguments on Emancipation

In these two letters, Lincoln explained the reasoning behind the Emancipation Proclamation, which went into effect on January 1, 1863. The Proclamation declared that “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” It also authorized formerly enslaved people to serve in the United States army. The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves only in states that were in rebellion and where, as a result, Lincoln could wield power as commander in chief of U.S. military forces. By contrast, in the four slave states that remained in the Union, Lincoln lacked such military authority and had to defer to Congress and state legislatures. One month before the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln proposed that Congress adopt a plan of gradual, compensated emancipation, designed to eliminate slavery throughout the United States. His proposal did not become law. Through the passage of various state laws and, ultimately, the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, slavery became illegal throughout the nation by the end of 1865.

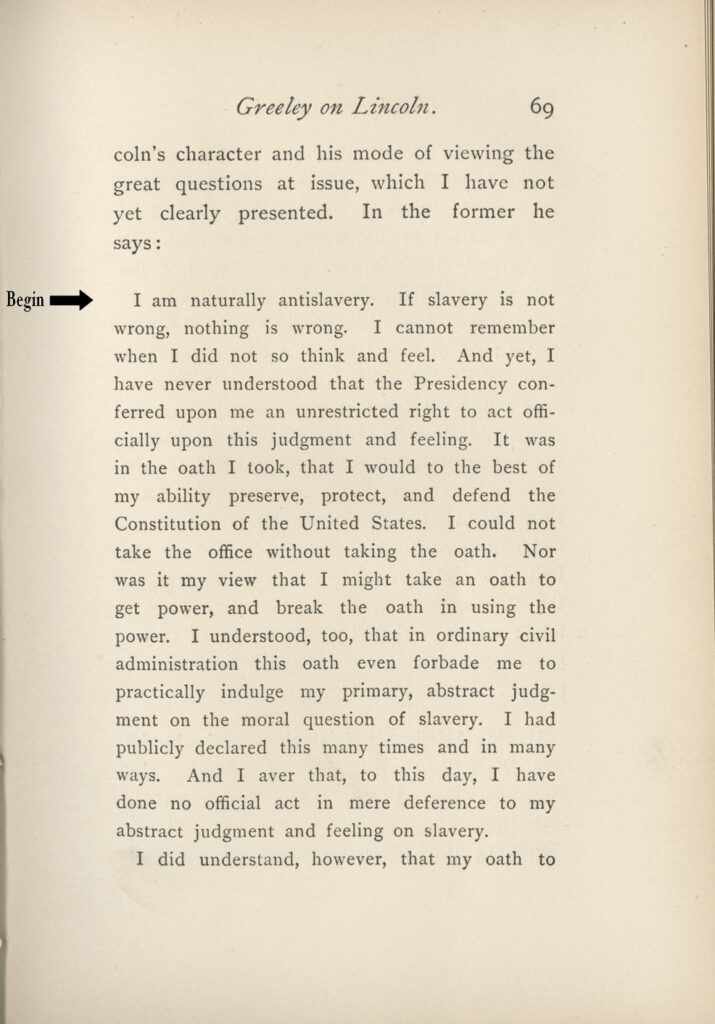

Selection: Abraham Lincoln to Albert Hodges, in Greeley on Lincoln, 69-70 (April 4 1864).

Lincoln wrote the first letter included here in response to a request from supporters that he speak at a rally in his hometown of Springfield, Illinois, on September 3, 1863. Unable to attend the rally, he asked his longtime friend, James C. Conkling, to read the letter on his behalf. This letter was also sent to the New York State Union Convention, which was held at the same time. Lincoln wrote the second letter on April 4, 1864, at the request of Albert Hodges, a Kentucky newspaper editor. In that letter, Lincoln restated thoughts he had voiced in a conversation with Hodges and two prominent Kentucky politicians. The letter illuminates Lincoln’s changing position on the question of emancipation.

Questions to Consider:

- What arguments did Lincoln make for his authority to issue the Emancipation Proclamation? How would the Emancipation Proclamation contribute to the goal of saving the Union?

- How did Lincoln present the Emancipation Proclamation as serving a military purpose? Why do you think he felt compelled to make this argument? Did that rationale for the Emancipation Proclamation support or conflict with the document’s moral significance?

- What distinctions did Lincoln draw between his personal position on slavery and the position that he took as the president of the United States? Why did he make that distinction? What did he see as his primary obligation as president?

- What did Lincoln mean when he used the metaphor of amputating a limb to save a life? Why do you think he chose a metaphor of the body to represent the nation?

The Fugitive

Enslaved people had always wanted to be free, and before the Civil War, some managed to escape slavery and flee to the free states. Freedom seekers who reached the North became especially potent political and cultural figures after the Compromise of 1850, a collection of legislation that included a federal law designed to help slaveowners claim people who escaped to free jurisdictions. That law, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, required all Americans to assist in the capture of fugitives or face fines and imprisonment. It permitted officials to remove alleged fugitive slaves to the slave states without hearing their claims to freedom. The new law made all Black people living in the free states vulnerable to kidnaping. Many white Northerners felt that it made them fully—and newly—complicit in the institution of slavery. Representations of freedom seekers played a crucial role in abolitionist literature, whether autobiography, such as Frederick Douglass’ Narrative, or fiction, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

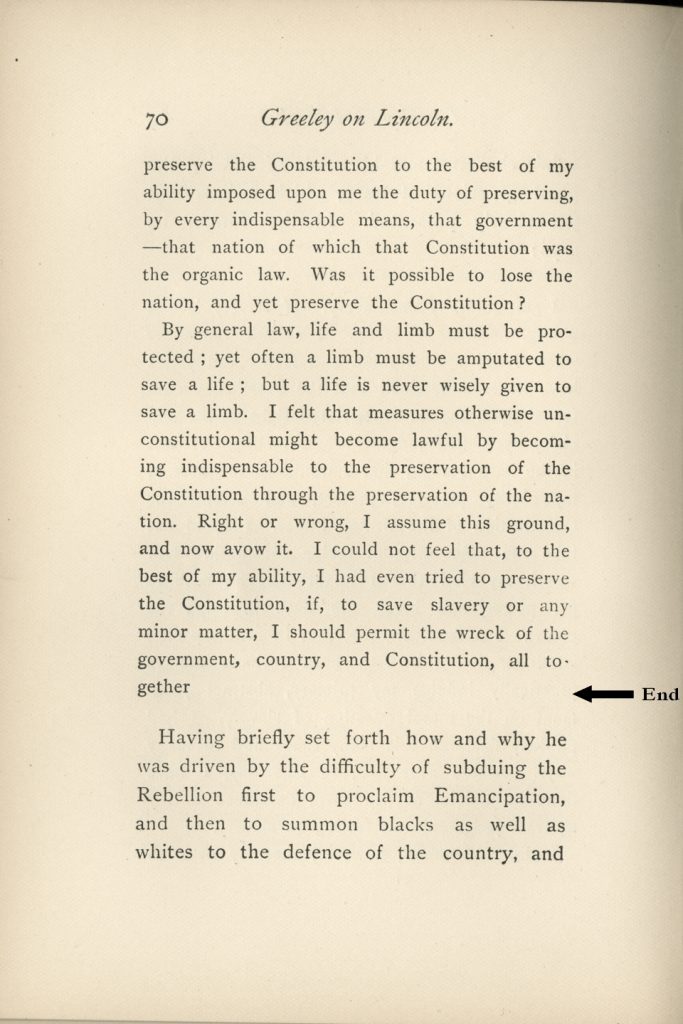

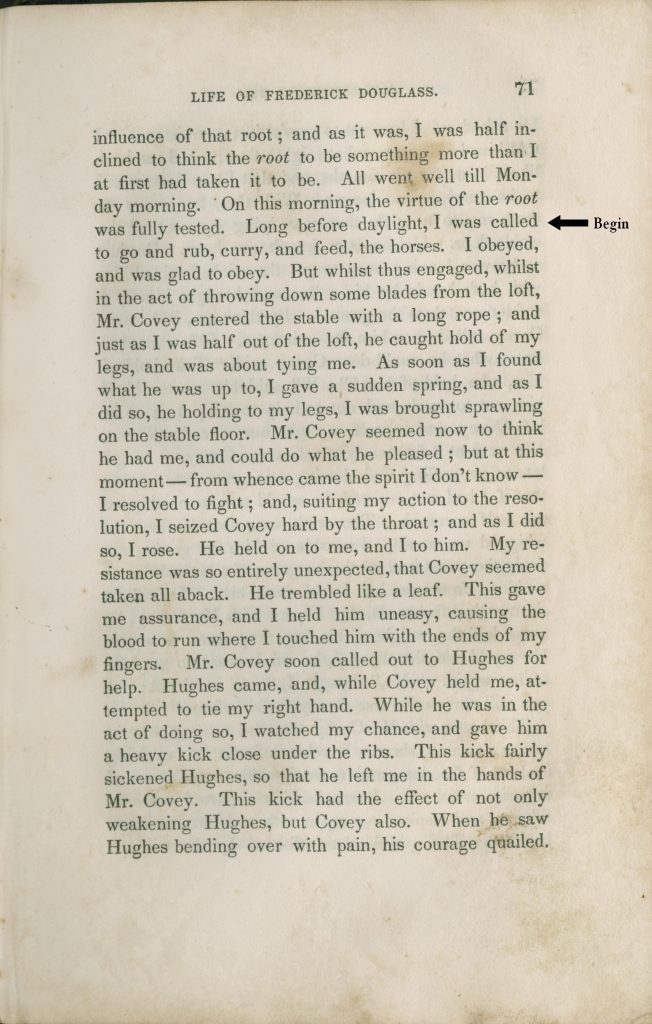

Selection: Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, title page and frontispiece, 71-73 (1845).

Questions to Consider:

- Frederick Douglass introduced this account of his “battle with Mr. Covey,” the plantation overseer, by telling the reader, “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.” Why did Douglass present slavery and manhood as mutually exclusive? In what sense did this physical confrontation transform Douglass from a slave into a man?

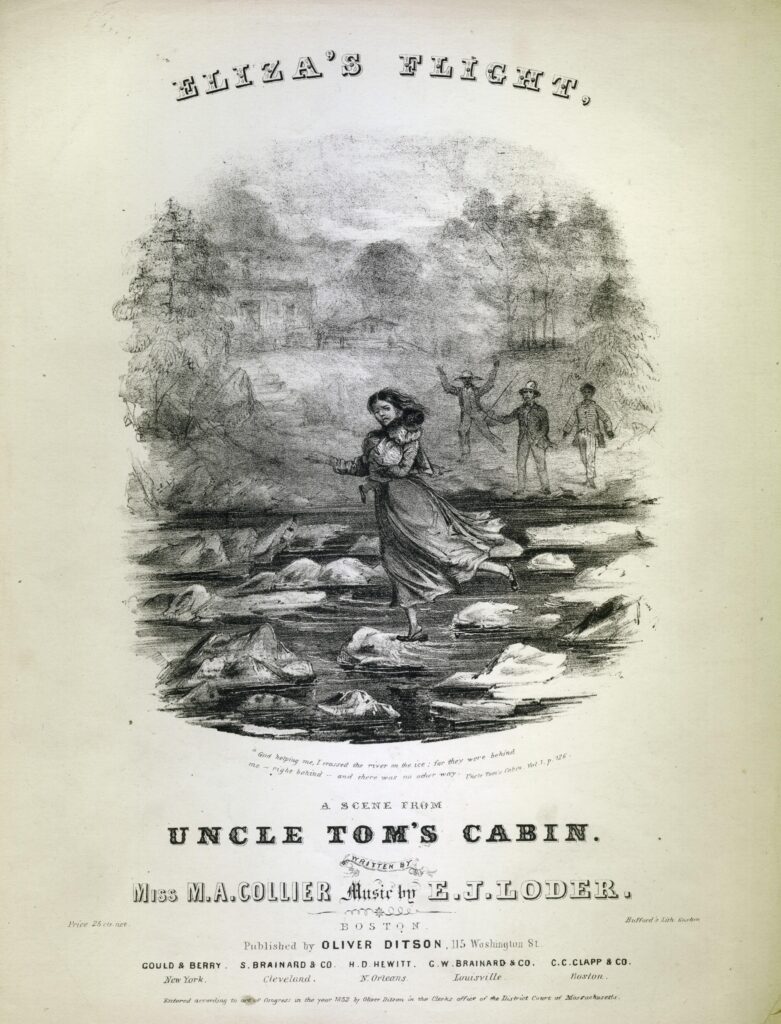

- Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, inspired artists and musicians throughout the North to create works based on the novel’s characters. In this famous scene, the enslaved woman Eliza leaps across the ice floes on the Ohio River, clutching her small son. The slave trader Haley and his assistants look on in anger and helplessness, unwilling to attempt to cross the river themselves. How was this scene designed to elicit readers’ sympathy for the abolitionist cause?

- Compare the representations of resistance and freedom in this passage from Douglass’ autobiography and the scene from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. What meanings of freedom represented in these works? How do they present enslaved people as heroes?

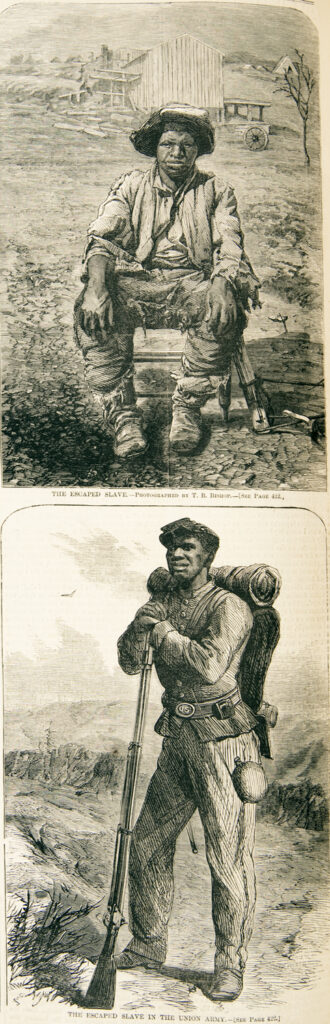

- Examine the two engravings of “The Escaped Slave” that appeared in Harper’s Weekly magazine. he man had fled from Montgomery, Alabama, to enlist in the United States Army. Compare the man’s clothing, expression, and posture in the two images. How had his appearance changed?

- William Still was a prominent abolitionist and participant in the Underground Railroad, the network of secret routes and safe houses that helped slaves escape to the North and Canada. After the Civil War, Still collected and published a book containing stories and illustrations of people’s efforts in the Underground Railroad. One of these stories concerns Henry Box Brown, who escaped slavery by packing himself into a crate and mailing himself from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Why is this illustration titled “The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown”? What are the possible meanings of the word resurrection in this context?

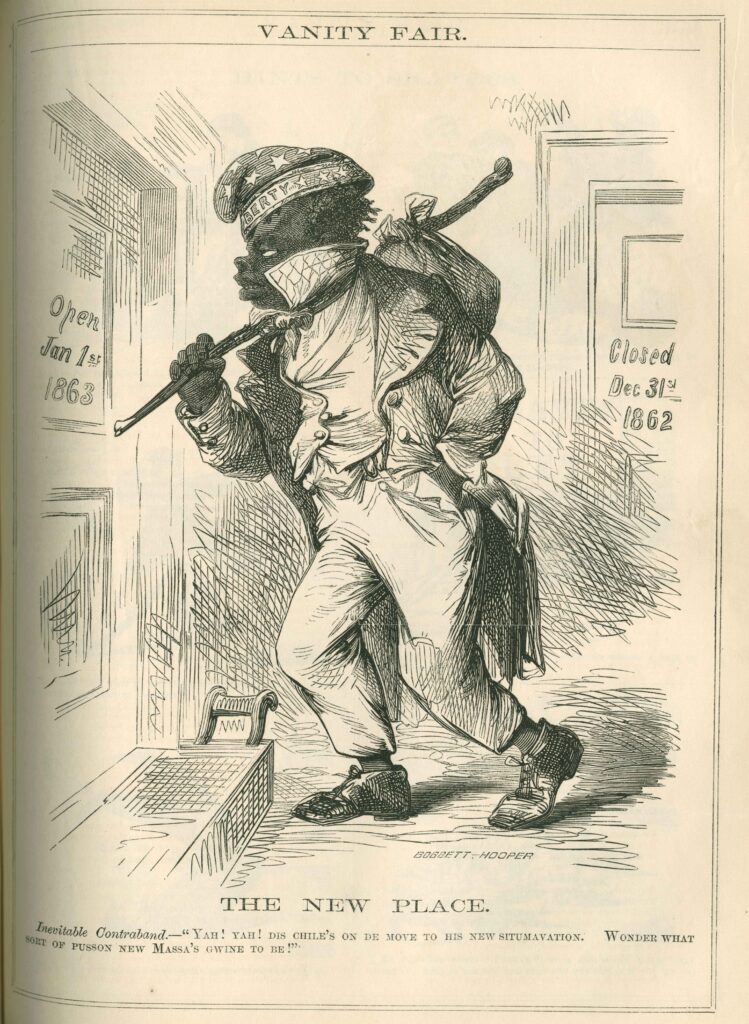

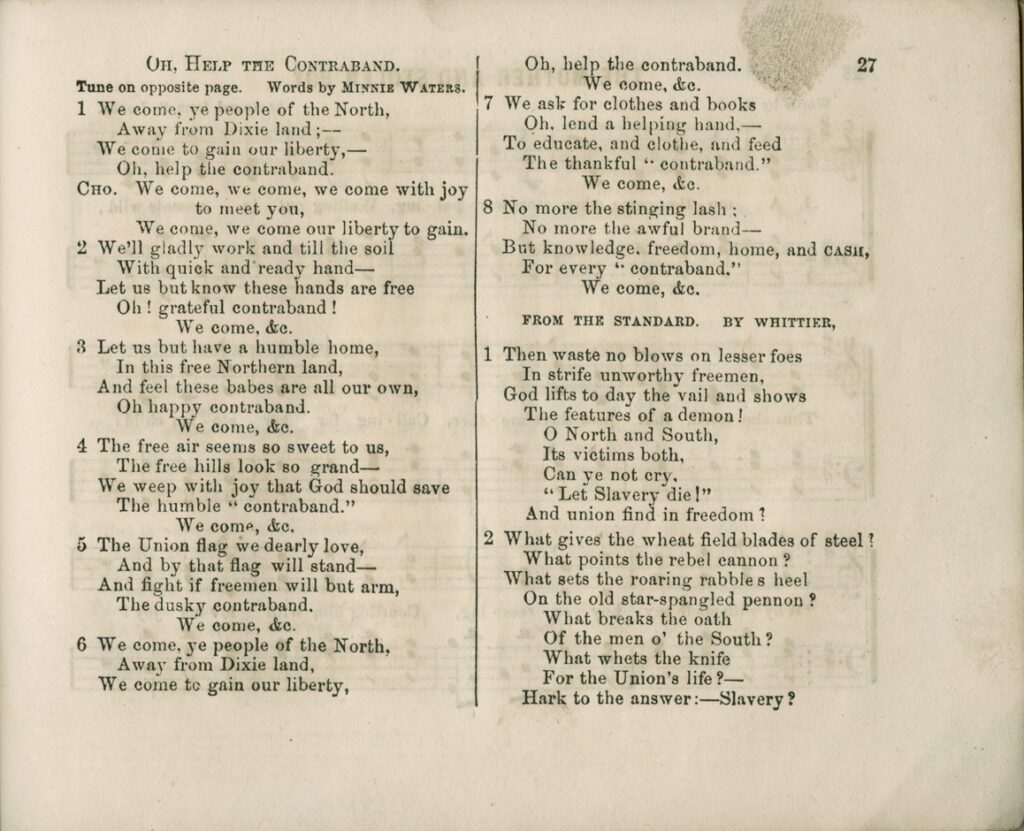

The Contraband

As historian Kate Masur explains, Northerners began to use the term contraband to refer to escaped slaves within weeks of the start of the Civil War. Three enslaved men approached the U.S. general Benjamin F. Butler at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, in May 1861. Their owner, a Confederate officer, soon demanded that the U.S. soldiers allow him to take the men back into slavery. Butler was not sure what to do. Lincoln had recently said his administration had no intention “to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists.” But Butler had no desire to give the Confederate colonel what he wanted. So Butler invented a policy on the spot. He declared the men “contraband of war,” meaning that they were “property destined for use in the enemy’s war effort,” and could therefore be held by U.S. troops. Butler’s contraband policy was soon superseded by a federal law authorizing U.S. soldiers to refuse to cooperate with Confederate sympathizers seeking to recapture freedom seekers. Yet, Masur writes, “as a name for fleeing slaves, ‘contraband’ had significance…beyond anything Butler could have predicted… The term jumped immediately into popular culture” and was widely used in Northern publications until the end of the war. Masur argues that the term’s popularity illuminates “the transitional status of the people to whom it referred. They were neither property with a clear owner (as in slavery) nor free people, but something in between.” Representations of escaped slaves as contraband were at least as likely to play on white Northerners’ fears of the consequences of emancipation as they were to celebrate abolition.

Questions to Consider:

- The song “Oh, Help the Contraband” was published by antislavery activists. According to its lyrics, what do the contraband desire from the “people of the North”? What did liberty mean to the contraband? How did the song try to reassure people in the North that former slaves would indeed become good citizens?

- Examine the engraving “The New Place” and its caption, which appeared in the New York humor magazine Vanity Fair days before the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. How did this illustration portray the newly freed slave? Describe the man’s dress, posture, and facial expression. Why did the caption describe this “contraband” as “inevitable”? What does the man’s speculation about a “new massa” suggest about his readiness for freedom and citizenship?

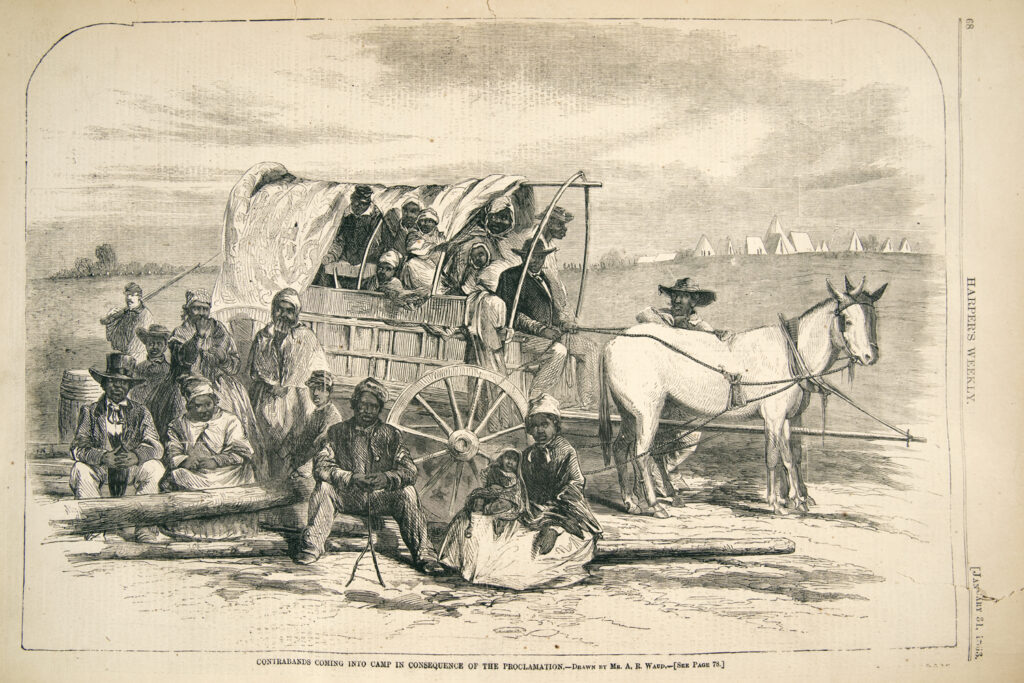

- Describe people’s appearances in the two Harper’s engravings below that portray freedom seekers joining U.S. troops. What are their ages and genders? How are they dressed? What emotions do their postures and faces convey? What do the images suggest about the condition of slavery, the process of escape, or the potential for freed people to become full citizens?

- Compare the images and texts portraying the “contraband” to those grouped under the heading “The Fugitive.” In what ways are the documents similar and in what ways are they different?

Selection: Engravings from Harper’s Weekly showing escaped slaves: “Contrabands Coming into Camp in Consequence of the Proclamation (January 31, 1863) and “The Effects of the Proclamation” (February 21, 1863).

Post-Emancipation

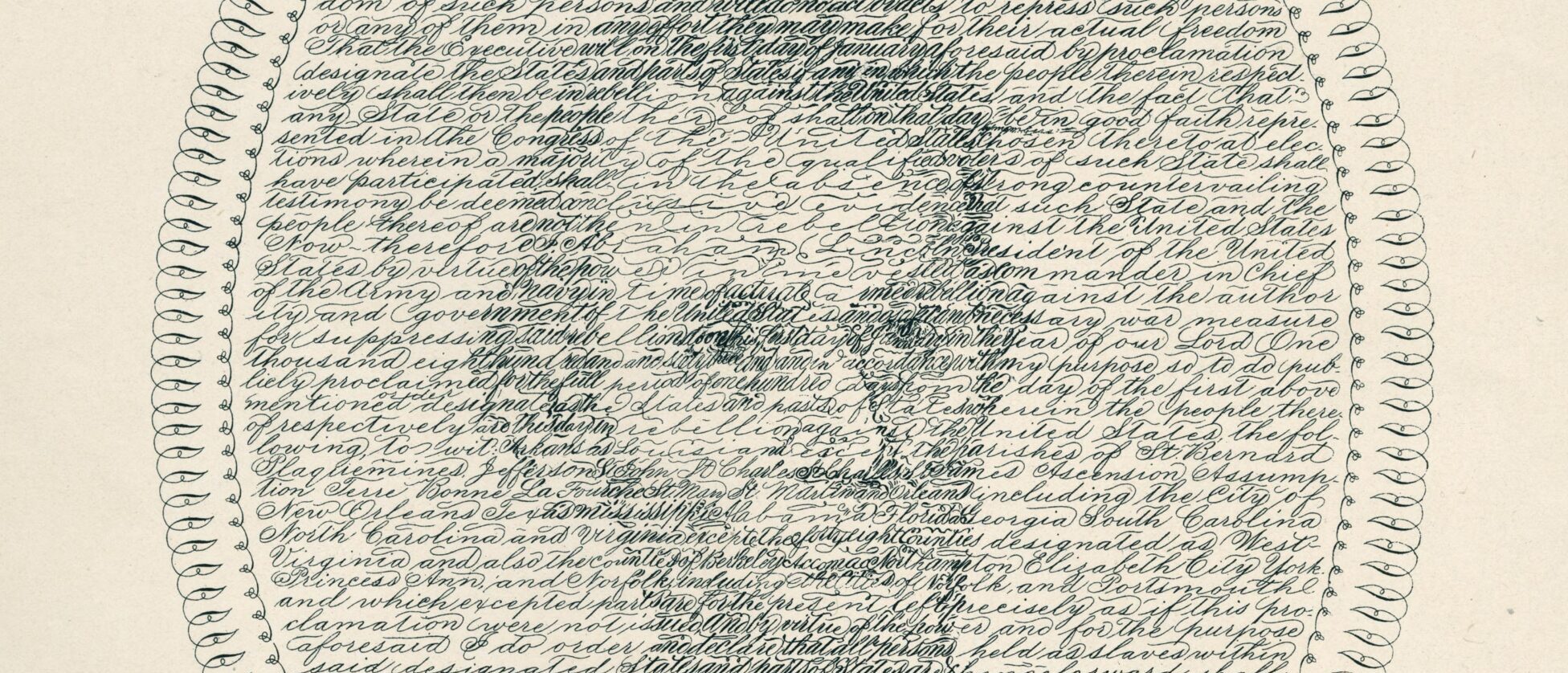

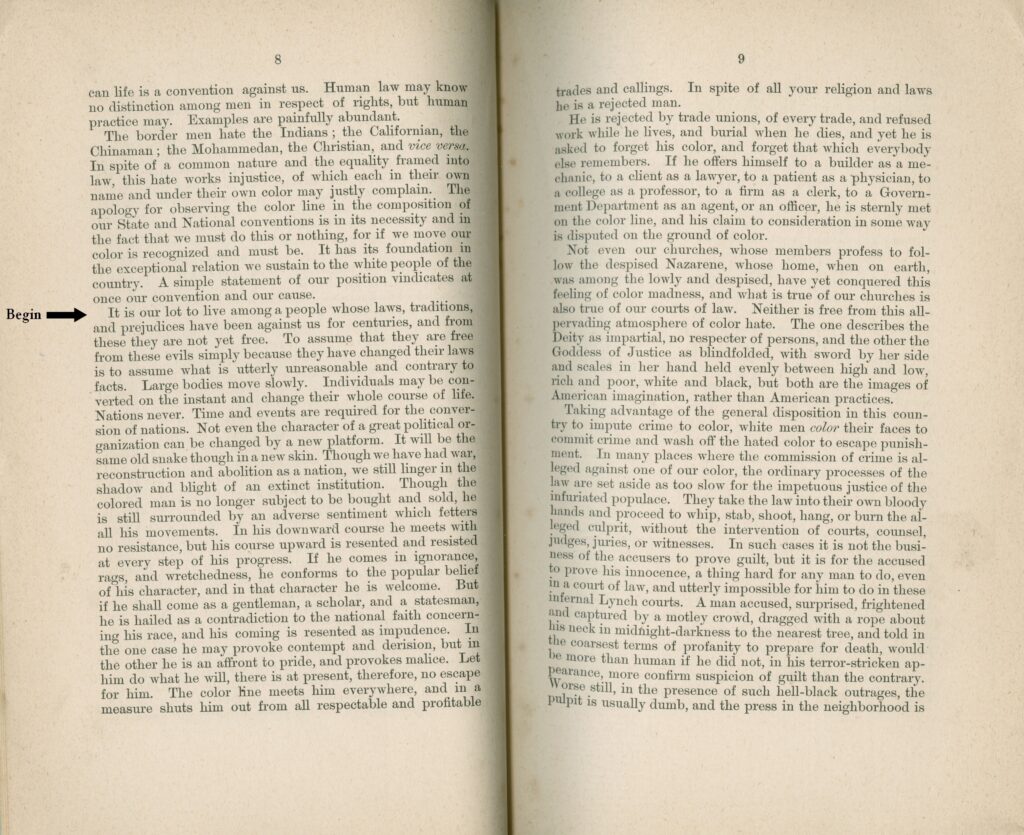

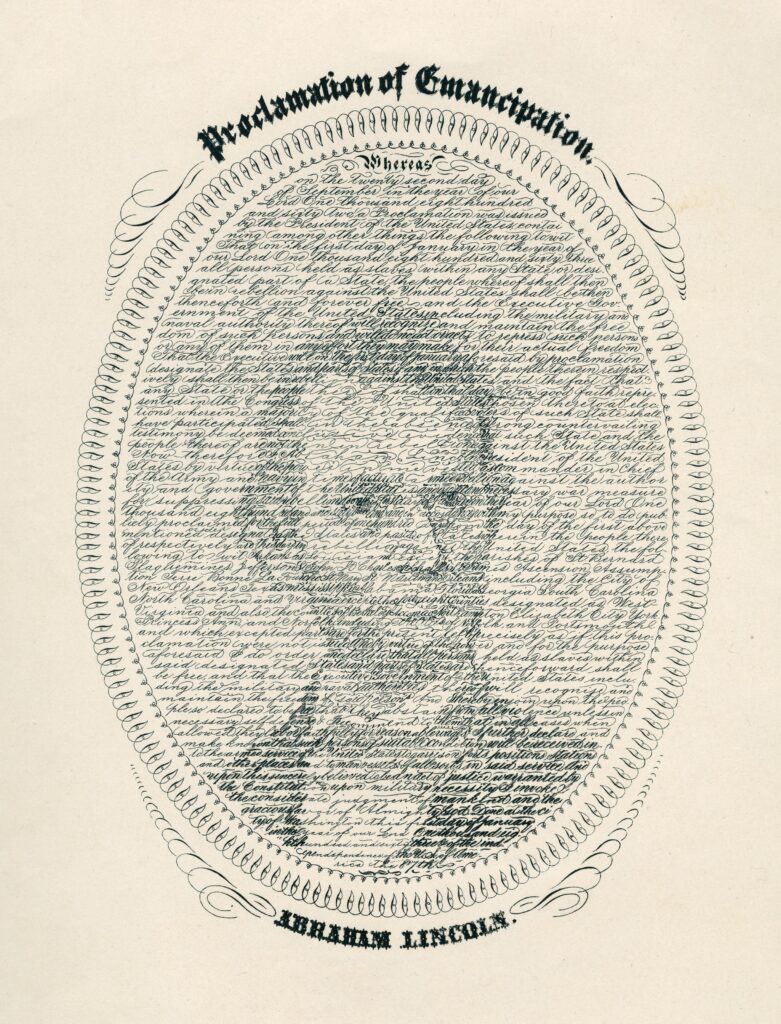

The documents in this section approach the legacy of the Emancipation Proclamation from two different directions: first, in relation to Lincoln’s reputation and, second, in relation to the status and experiences of African Americans during Reconstruction. The portrait of Lincoln was created by W. H. Pratt in 1867, two years after Lincoln’s assassination and the end of the Civil War. The words of the Emancipation Proclamation are written in calligraphy across the page to form a drawing of Lincoln’s face. The second document, an excerpt of an 1883 speech by Frederick Douglass, addressed the nation’s continuing failure to fulfill its commitment to African American freedom and citizenship. Douglass had escaped slavery in 1838 and became a prominent writer and orator for abolition, women’s suffrage, and racial justice.

Selection: Frederick Douglass, Speech in Louisville, KY, in Three Addresses on the Relations Subsisting between the White and Colored People of the United States, 8-10 (1883)

Questions to Consider:

- How did Pratt’s portrait of Lincoln commemorate the president? What does the portrait suggest about the status of the Emancipation Proclamation among all of Lincoln’s actions?

- What do you think Douglass meant by the phrase “the color line”? What social, economic, and political conditions did African Americans face in the 1880s, according to Douglass? How did Douglass’ concerns about the condition of African Americans following emancipation compare to the concerns of white Northerners expressed elsewhere in this document collection?

Slavery and the Emancipation Proclamation

The map below portrays Lincoln and the Republican Party’s opposition to the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act for allowing slavery to advance into new territories, while the letters by Lincoln included below–both written after the Emancipation Proclamation and less than a year apart–capture his evolving position on the question of emancipation.

Representations of Freedom Seekers

Documents like these ones below–which range from the autobiographical account of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass and an illustration inspired by the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin to sheet music and an array of magazine publications–depict various representations of freedom seekers, which played a crucial role in abolitionist literature.

Post-Emancipation

These documents, an 1867 portrait of Lincoln after his death and an 1883 speech by Frederick Douglass, speak to the legacies of the Emancipation Proclamation in shaping the memory of Lincoln and the experiences of African Americans during Reconstruction.

Further Reading

Leslie M. Harris. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863. 2003.

Library of Congress. With Malice Toward None: The Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Exhibition [online exhibit]. http://myloc.gov/Exhibitions/lincoln/Pages/Default.aspx.

Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln, Slavery, and the Civil War. Edited by Michael P. Johnson. 2011.

Kate Masur. “‘A Rare Phenomenon of Philological Vegetation’: The Word ‘Contraband’ and the Meanings of Emancipation in the United States.” Journal of American History (March 2007): 1050–1084.

Newberry Library and Chicago History Museum. Lincoln at 200 [online exhibit]. http://publications.newberry.org/lincoln.

Terra Foundation for American Art. The Civil War in Art: Teaching and Learning through Chicago Collections. www.civilwarinart.org.