Curriculum Connections: Abolitionism, African American History, Chinese Exclusion Act, Native American and Indigenous History, US Civics, Westward Expansion, World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893

Materials – Available for Download in the Downloads Tab:

- A copy of the “Perspectives on the United States” lesson

- Copies of the excerpts used in the lesson

- Student worksheet for this lesson

You and your students are going to read excerpts from Frederick Douglass’s famed Fourth of July speech and from the less well-known book The Red Man’s Greeting (originally The Red Man’s Rebuke), written by Simon Pokagon of the Pottawattamie people.

Process

This lesson is for a teacher-controlled class. It is primarily a compare-and-contrast exercise, looking at texts by two people who were left out of the promise of the United States. Each excerpt could also be taught individually.

Possible questions to spark students’ initial investigations are listed after each excerpt. Then there is a list of potential compare-and-contrast questions. If necessary, explain how to read attributions and use the background material at the end of this lesson to provide more context. If you would like your students to work with the source independently or in small groups, you can download a worksheet in the Student Worksheet tab or copies of the excerpts in the Downloads tab.

Display or distribute the excerpts. If possible, have students read the excerpts and write down their questions and ideas without providing them any information about the authors or the context. Then, engage students in an examination of the texts through their questions and the potential questions suggested here.

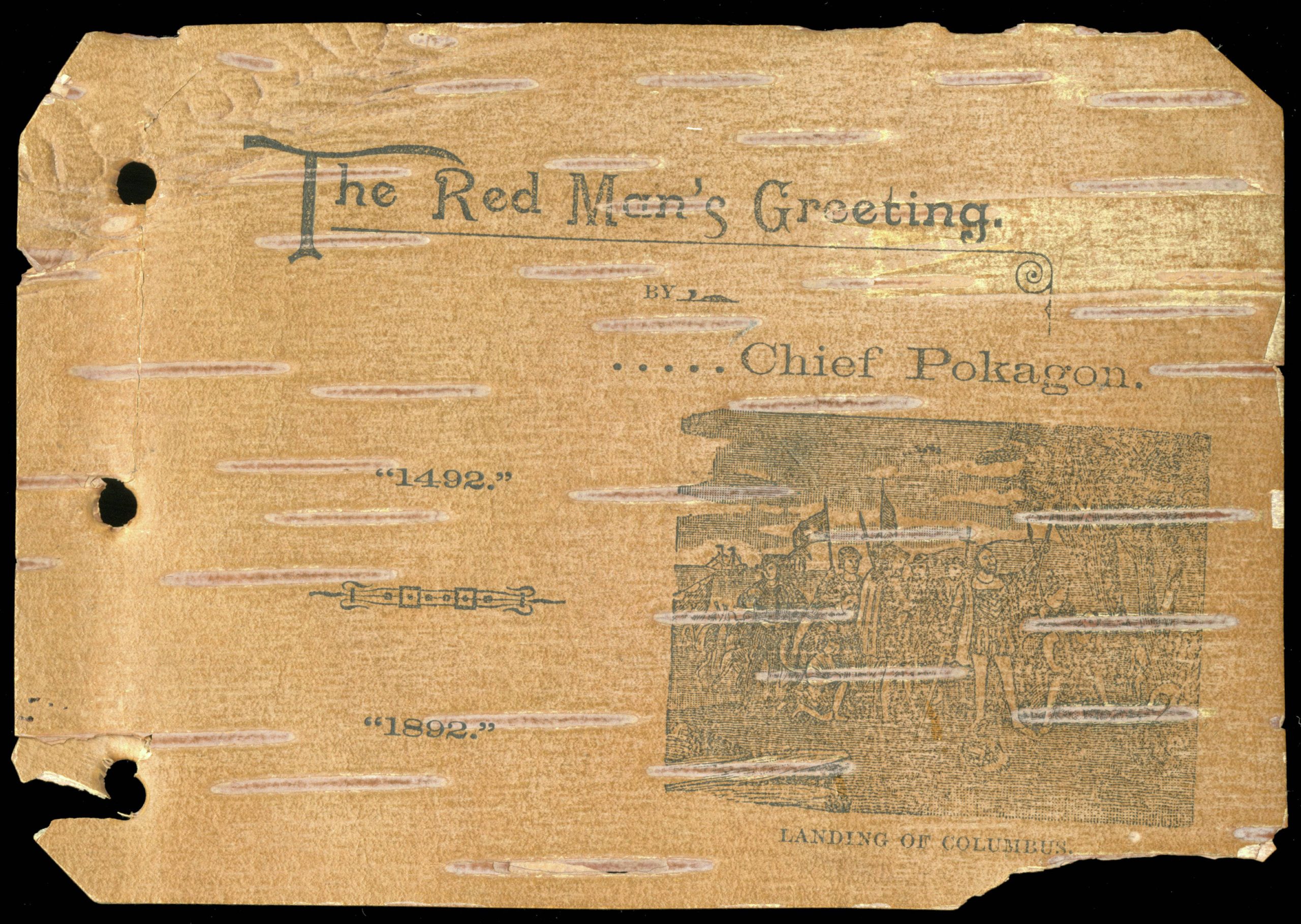

Source 1: Excerpt from The Red Man’s Greeting, 1492-1892

In behalf of my people, the American Indians, I hereby declare to you, the pale-faced race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in this Chicago city, the wonder of the World.

No; sooner would we hold high joy-day over the graves of our departed fathers, than to celebrate our own funeral, the discovery of America. And while you who are strangers, and you who live here, bring the offerings of the handiwork of your own lands, and your hearts in admiration rejoice over the beauty and grandeur of this young republic, and you say, “Behold the wonders wrought by our children in this foreign land,” do not forget that this success has been at the sacrifice of our homes and a once happy race. . . .

But alas! the pale-faces came by chance to our shores, many times very needy and hungry. We nursed and fed them, — fed the ravens that were soon to pluck out our eyes, and the eyes of our children ; for no sooner had the news reached the Old World that a new continent had been found, peopled with another race . . . then, locust-like, they swarmed on all our coasts and, like the carrion crows in spring, that in circles wheel and clamor long and loud, and will not cease until they find and feast upon the dead, so these strangers from the East long circuits made, and turkey-like they gobbled in our ears, “Give us gold, give us gold ; ” “Where find you gold ? Where find you gold ? ”

We gave for promises and “gewgaws” all the gold we had, and showed them where to dig for more ; to repay us, they robbed our homes of fathers, mothers, sons, and daughters; some were forced across the sea for slaves in Spain, while multitudes were dragged into the mines to dig for gold, and held in slavery there until who escaped not, died under the lash of the cruel task-master. . . . Our hearts were crushed by such base ingratitude ; and, as the United States has now decreed, “No Chinaman shall land upon our shores,” so we then felt that no such barbarians as they, should land on ours.

Chief Simon Pokagon, The Red Man’s Greeting, 1492–1892, by Chief Simon Pokagon, 1-3. (images 7, 10, 11 on Digital Newberry)

Potential Questions

- Who wrote this excerpt? Who was it written for? Why was it written? When was it written? How do you know?

- From this excerpt, can you tell what type of source it’s from (e.g., book, article, speech, diary, interview, etc.)? Where might you find out more about the source of this excerpt?

- What can you determine about the author of this text? How did you come to that conclusion?

- What do you not know about the author? What questions do you have about him?

- What information does your background knowledge of Columbus’s journeys, the settlement of the Americas, and the American Indian experience give you about the author and this excerpt?

- What does this excerpt have to do with the Chinese Exclusion Act? How do you know?

- Does anything in this excerpt surprise you?

- What questions does this excerpt raise? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Source 2: Excerpt from “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us? . . . I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. — The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day? . . . Fellow-citizens; above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them . . .

O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. . . . What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour. Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Potential Questions

- What type of text is this excerpt from (e.g., book, article, speech, diary, interview, etc.)? How might that have influenced how it was written? Who was the audience for it?

- Who is the author? Have you heard of him before? Do you have any questions about him? How does your knowledge about him help you understand or think about this excerpt?

- What can you determine about when this speech was written based on the information in this excerpt?

- How does your background knowledge of slavery in the United States affect your understanding of this excerpt?

- Does anything in this excerpt surprise you?

- What questions does this excerpt raise? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Potential Questions to Compare and Contrast the Excerpts

- What are the different perspectives each author brings to their texts?

- The authors of these texts wrote them to commemorate a specific occasion. How do those occasions relate to what they write or speak about?

- What are the authors’ experiences of the United States? How are they different and how are they similar?

- Does reading excerpts from both these texts rather than just one of them influence your thinking? If so, in what ways? If not, why not?

- How do each of these texts challenge the idea of the United States?

- Are the authors’ critiques of the United States fair or not? Why or why not?

- Has the United States addressed the inequities that the two excerpts discuss? If yes, in what ways?

Advanced Close Reading Questions

- What stands out about the word choices made by each author? What words or phrases were particularly effective? What words or phrases were less effective?

- What rhetorical devices or emotional language do the authors’ use?

- Imagine hearing these excerpts delivered by the speakers. What are the rhythms of the language? How do those rhythms affect the message of each?

- Do you think one author is more effective than the other? If so, why? If not, why are both authors equally effective?

Background

The word pale-face (or paleface) first came into use as a term for white people in North America around 1823. It has been used by both white people writing stereotypical American Indian speech and by American Indians as a derogatory term.

The word gewgaw, meaning a gaudy trinket, bauble, or ornament of little value, has been in use since at least the sixteenth century.

Frederick Douglass (c. 1818–1895) successfully self-emancipated and became a famous abolitionist, women’s rights advocate, newspaper publisher, and lecturer. In 1852, the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester, New York, where he had made his home, asked him to give a speech at their 4th of July celebration. The celebration actually took place on July 5 because July 4 fell on a Sunday that year and secular celebrations were not held on the Sabbath. Douglass’s speech is one of history’s greatest.

Chief Simon Pokagon (1830–1899) of the Potawatomi people was nationally known in his day. He visited President Abraham Lincoln at the White House twice while trying to get payment for the lands ceded in the 1833 Treaty of Chicago. By the 1890s, he was claiming land on Chicago’s lakefront. Over time, Pokagon lost the support of many others in his band. Pokagon wrote extensively on American Indian issues throughout his life. He was a guest of honor and gave a speech at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893.

Much of Pokagon’s writing was published on birchbark, including the book excerpted here, The Red Man’s Rebuke (later renamed The Red Man’s Greeting). He explains this choice in the frontispiece: “My object in publishing the ‘Red Man’s Greeting’ on the bark of the white birch tree, is out of loyalty to my own people, and gratitude to the Great Spirit, who in his wisdom provided for our use for untold generations, this most remarkable tree with manifold bark, used by us instead of paper, being of greater value to us as it could not be injured by sun or water.” Pokagon is also studied today for his environmental writing, which will be explored in future Newberry classroom material.

Extension Activities

Have students read the National Woman Suffrage Association’s “Declaration of the Rights of Women,” distributed by Susan B. Anthony on July 4, 1876, in Philadelphia, and compare and contrast this declaration with the two speeches in this lesson.

Additional Resources

- The full text of The Red Man’s Greeting.

- The full text of “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

- Collection Essay “Lincoln, the North, and the Question of Emancipation.”

Words to Know

attribution | the line after a quote or excerpt which names the author, title, or date of the work being excerpted

Sources in this lesson come from the Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection and the Collection Essay “Lincoln, the North, and the Question of Emancipation.”

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the “Perspectives on the United States” lesson

- Copies of the excerpts used in the lesson

- Student worksheet for this lesson

Related Newberry Resources

A custom curriculum hosted by the Newberry and centered on Chicago as a Native Place.

Created in alignment with Illinois State Standards and to support the HB1633 mandate to teach Native history.