Introduction

How did the Civil War transform the daily lives of people who lived hundreds of miles from the front lines? Most of the battles of the Civil War occurred either in border states or south of the Mason-Dixon line. As a result, civilians in border states and in the South encountered the Union and Confederate Armies themselves and witnessed the military conflict firsthand. Civilians in the North and West may not have had such direct experience of battle, yet many nevertheless found their daily lives transformed. Families sent soldiers and nurses to the southern battlefields. Northern women and men worked to provide the Union troops with necessities and comforts—clothes, bandages, ammunition, food. They mourned the dead—more than 360,000 men from the North alone—and they received the surviving veterans, many severely wounded, who made their way back home.

In the North, popular illustrations, along with photographs and paintings, made up a rich visual culture related to the war.

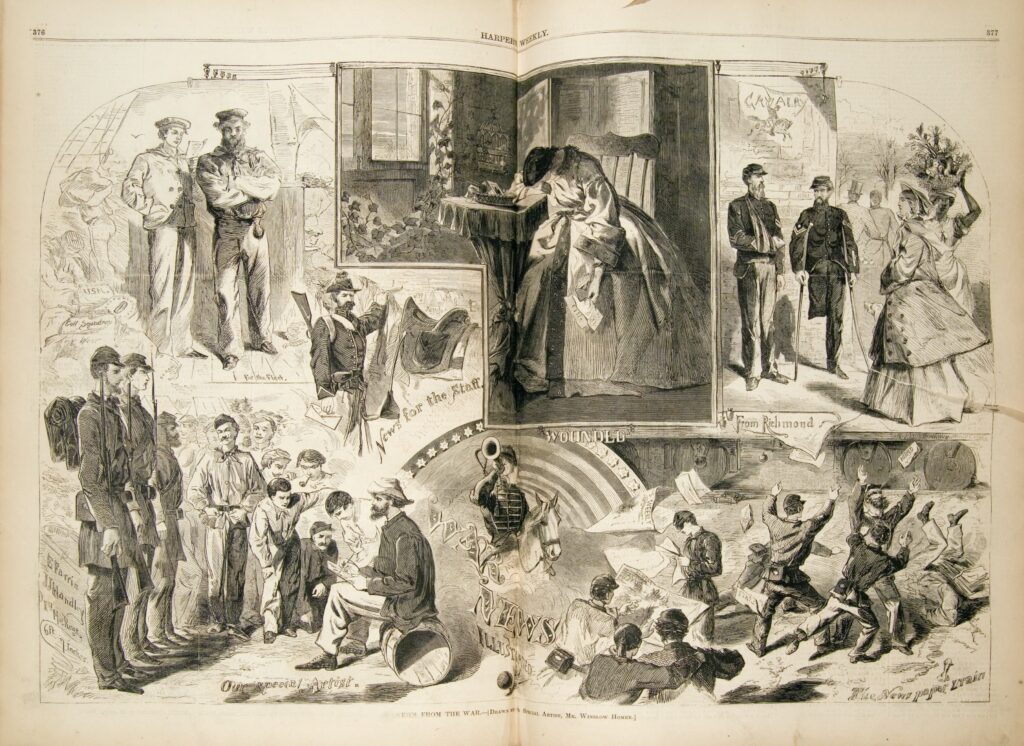

Beyond the demands of the war effort, Northerners experienced the Civil War from a distance in historically unprecedented ways. Historian Adam Goodheart notes that changes in printing practices meant that, for the first time, “Americans did not simply read the news—they saw the news.” This had not been the case for previous generations. People who lived during the American Revolution had to wait weeks or even months for news of the war, which arrived by word of mouth or in the cramped columns of local newspapers. But by the mid-nineteenth century, the North had a flourishing periodical press that not only delivered news faster, it illustrated the news in pictures. Weekly periodicals, such as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly, began printing large, woodcut illustrations in the years just before the Civil War and had circulations in the hundreds of thousands. The papers hired artists, such as Winslow Homer, to travel near the front lines and portray soldiers’ experiences on the battlefields and in Union military camps.

Periodical illustrations made up one part of a rich visual culture related to the war that developed in the North in the 1860s. The period is often referred to as the coming of age of photography. Photographs could not yet be effectively reproduced in large numbers, yet they had a profound cultural influence through the portrait studios that thrived in towns and cities throughout the North. Photographers such as Matthew Brady exhibited their works in galleries, introducing Northern audiences to devastating images of corpse-strewn battlefields. While some artists embraced the new standard of realism set by photography, others developed a strong, symbolic language to spur patriotic feeling. Both respected painters, such as Frederic Edwin Church, and popular illustrators, whose work appeared on sheet music and stationery, invested images of the U.S. flag with a new significance.

The following collection of documents brings together a wide range of images from sources both popular and highbrow in order to explore how visual culture shaped the meaning and experience of the Civil War home front. This digital collection is based on the 2013 Newberry Library and Terra Foundation for American Art exhibition Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North, curated by Peter John Brownlee and Daniel Greene.

Essential Questions

- What was the visual culture of the Civil War North? Which subjects related to the war did artists and publishers portray for audiences away from the front?

- How did artists use various media—painting, photography, printing—to convey the national experience of the war? What were the relationships between popular and elite forms of media?

- How did images shape the meaning of the war for people at home and the meaning of the home during wartime?

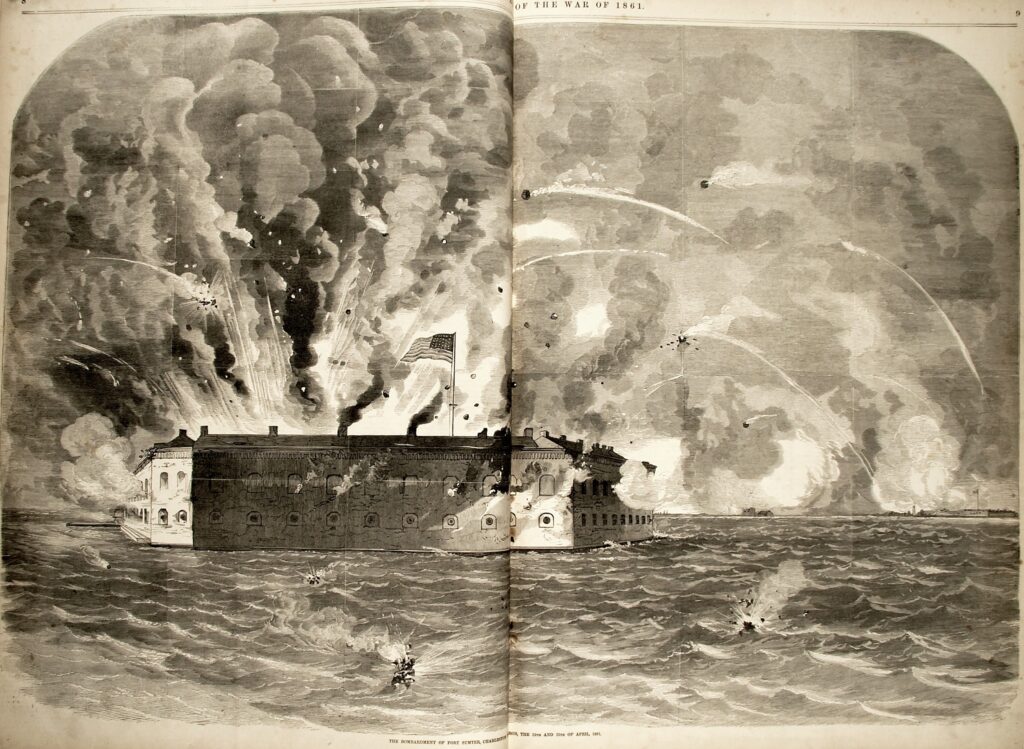

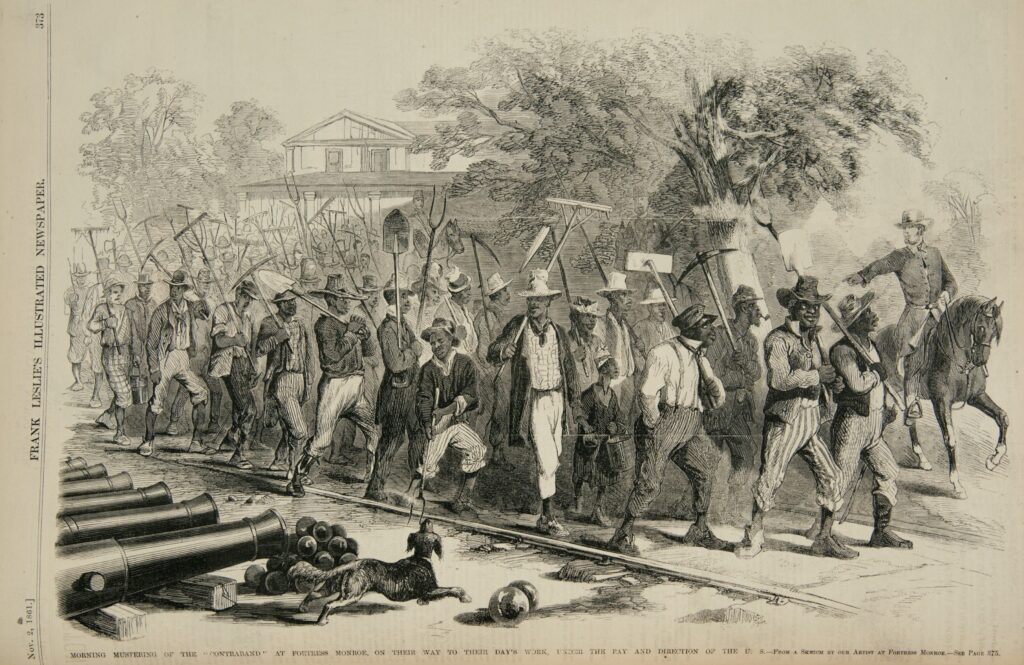

The War Illustrated

The illustrations in this section are drawn from the popular, New York–based weeklies Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly and suggest some of the ways these publications pictured the war for their readers. The first portrays the bombardment of Fort Sumter and was originally published on April 20, 1861, less than a week after the event itself. This spectacular representation of the outbreak of war contrasts with the seemingly mundane illustration that follows of the “Morning Mustering of the ‘Contraband’ at Fortress Monroe.” The term contraband refers to former slaves who had escaped into the protection of Union forces. If mustering normally suggests the routine activity of soldiers, in this case, it evokes radical social change—the prospect of freeing slaves more than a year before the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. (For more information, see “Contrabands Coming into Camp in Consequence of the Proclamation” in the collection Lincoln, the North, and the Question of Emancipation.)

“News from the War” presents a series of vignettes that depict the importance of wartime communication both to soldiers at war and to their families at home. The artist, Winslow Homer, went on to become one of the most-celebrated American painters of the nineteenth century. But he began as a commercial printmaker and, in October 1861, had been hired by Harper’s Weekly to serve as an artist-correspondent in Virginia.

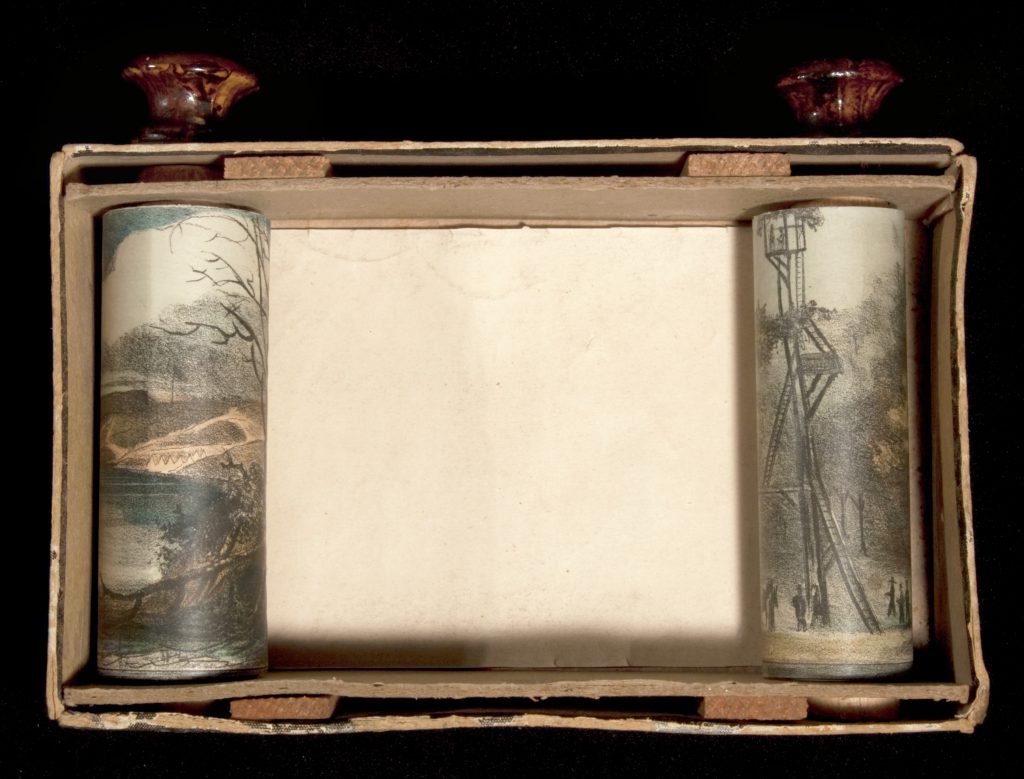

The final image below is of the Myriopticon, a miniature panorama produced by toy manufacturer Milton Bradley shortly after the war ended. The Myriopticon was a shoe-box-sized theater. It presented the history of the “Rebellion” on a scroll of 22 hand-colored illustrations copied from Harper’s and mounted on spindles in a cardboard box. A presenter could turn a crank to move the scroll from scene to scene, while reading from an accompanying script. The toy was so popular in some areas that neighbors would gather in the owner’s house to watch the show over and over. One child begged Bradley to sell more of the devices, so “as to make it less crowded in our parlor.”

Selection: The Myriopticon (1866)

Questions to Consider

- Describe the illustration “The Bombardment of Fort Sumter.” What details did the artist include in the scene? Would you describe the image as realist, in the manner of today’s newspaper photographs, or symbolic? Use evidence from the illustration to support your interpretation.

- How does the artist portray the gathering of “contraband” at Fort Monroe? In what ways do the men resemble soldiers and in what ways are they visibly different from soldiers? How do they relate to other figures in the scene such as the Union Army officer and the dog? Would you describe the “contraband” as dignified or comic?

- Compare the “Bombardment” and “Mustering” illustrations as representations of the war. Keeping the newspaper’s northern audience in mind, what does each image say about the larger significance or meaning of the war?

- Examine the scenes in Homer’s “News from the War.” What is happening in each scene? What does the illustration suggest about the role of periodicals, such as Harper’s, as well as private letters in wartime culture?

- Why do you think the Myriopticon appealed to consumers after the Civil War? What kind of historical narrative does it offer?

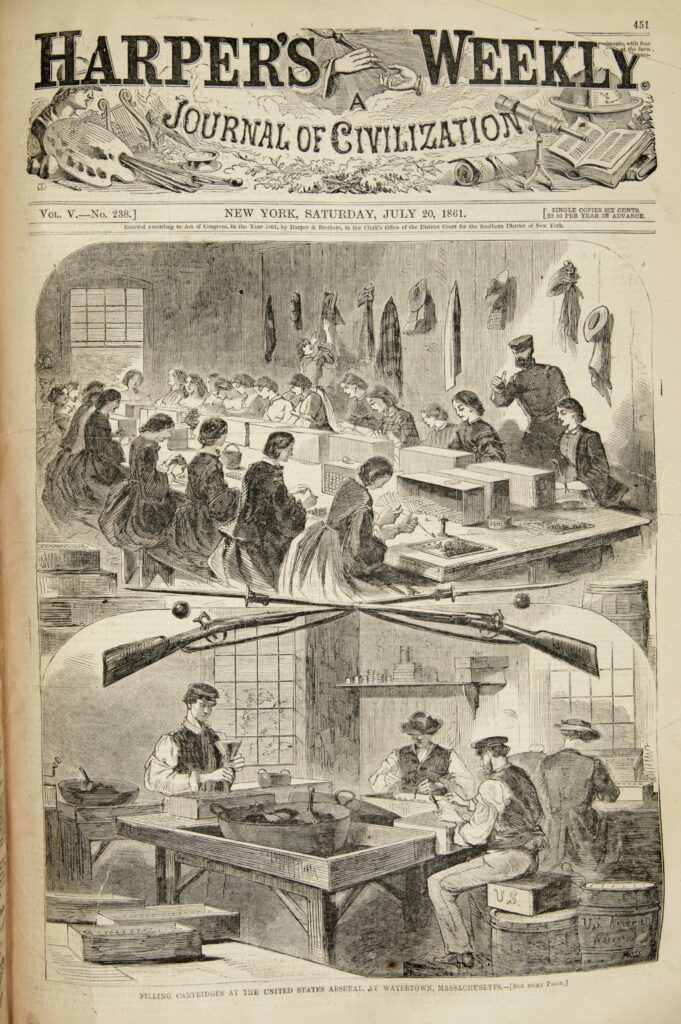

The Home at War

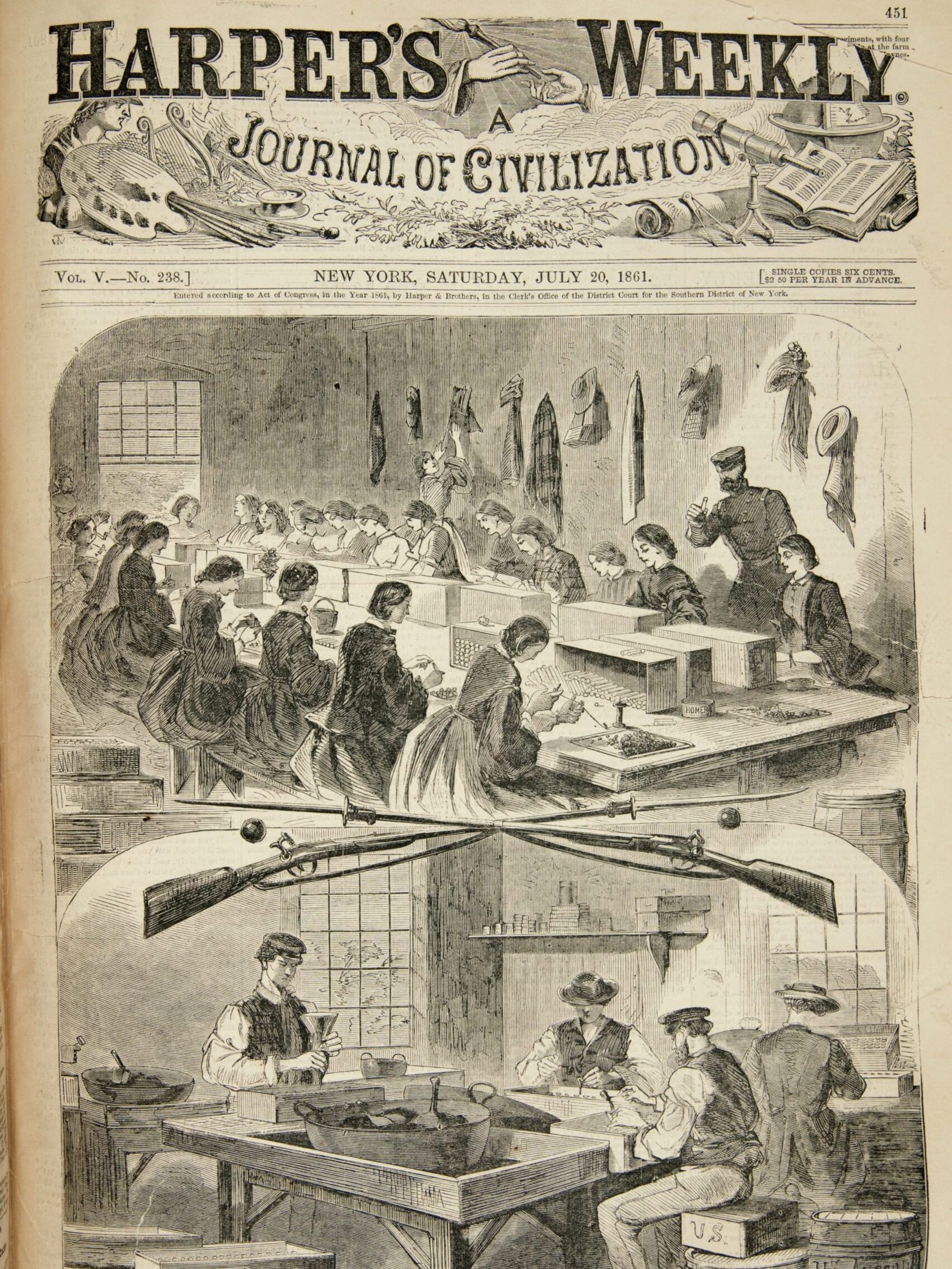

These two works by Winslow Homer suggest—directly and indirectly—some of the ways that the war changed the lives of civilians in the North. The 1861 cover of Harper’s shows men, on the bottom half of the page, filling paper cartridges with gunpowder. Women, on the top half, insert the bullets. The work was dangerous; in spaces full of live ammunition, the smallest spark could trigger a catastrophic explosion. Women in the North had worked in factories for decades, but the war greatly increased the necessity and the opportunity for women to take on wage labor outside the home. Homer’s 1864 painting On Guard portrays a boy watching over his family’s fields in his father’s absence, evoking changes to children’s lives as a result of the war.

Questions to Consider

- Describe the women and men at work in the Watertown arsenal. How does the illustration portray this aspect of the war effort? What does it suggest about the ways that women’s and men’s lives were changed by the war?

- Examine Homer’s painting On Guard and particularly the boy’s posture and expression. In what ways does Homer compare the boy to a soldier? How has the war transformed the home, according to this work?

The Iconography of Patriotism

The sources in this section are all quite different and provide a sense of the popularity of images of the U.S. flag in the Civil War North. Renowned landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church created Our Banner in the Sky in response to the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. The painting, on one level, exemplifies the allegorical and abstract approach to the war taken by members of the Hudson River school, at the time America’s most prominent fine arts movement. However, as the images that follow suggest, Church’s painting was one of many representations of the flag produced in the North during the war. Indeed, a New York publishing firm bought the copyright to Church’s painting, reproduced it as a lithograph, and sold numerous copies.

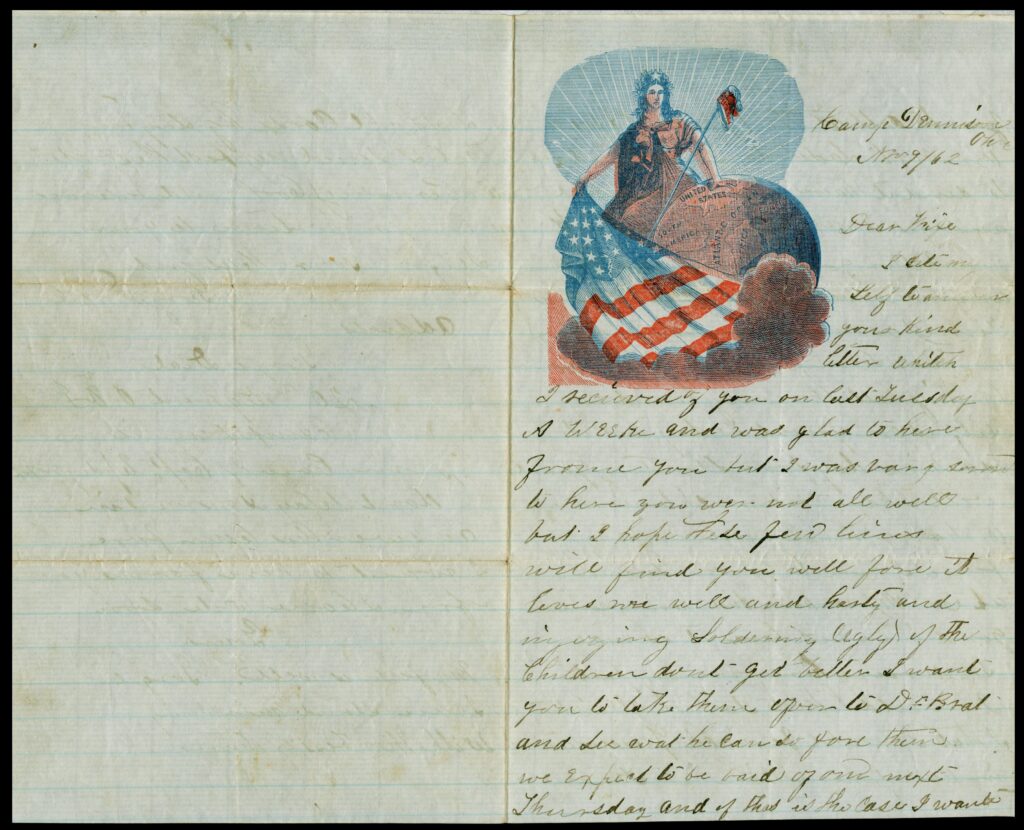

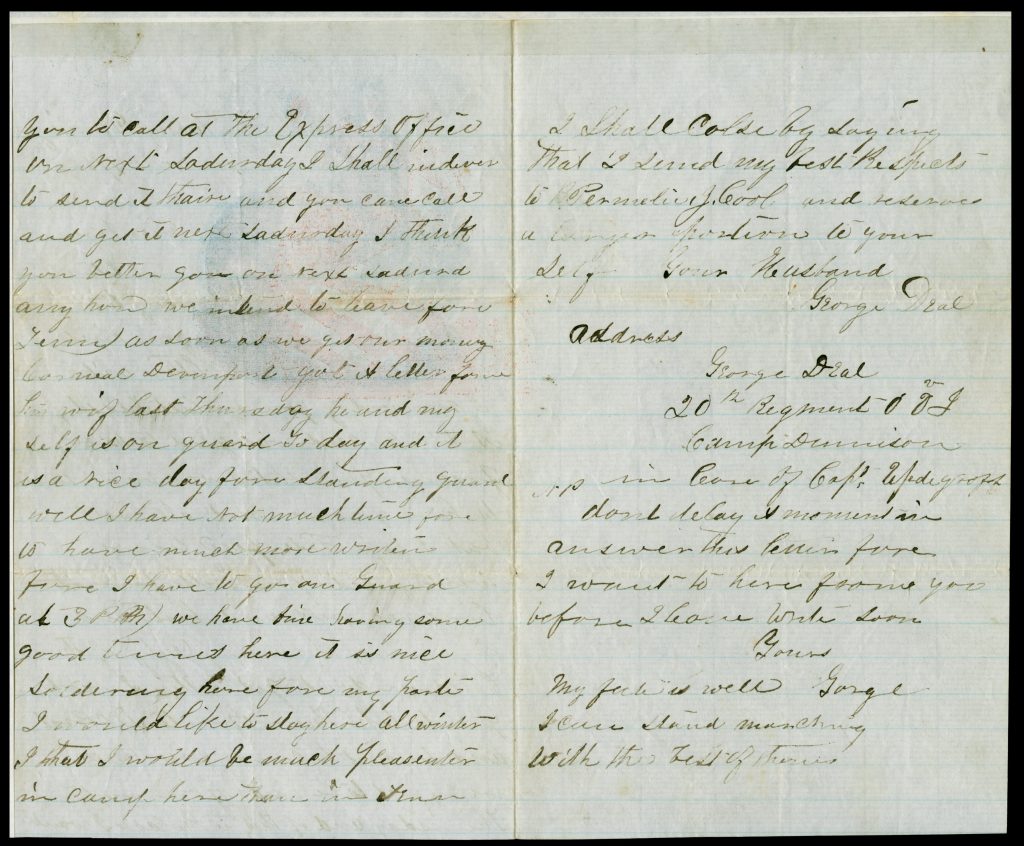

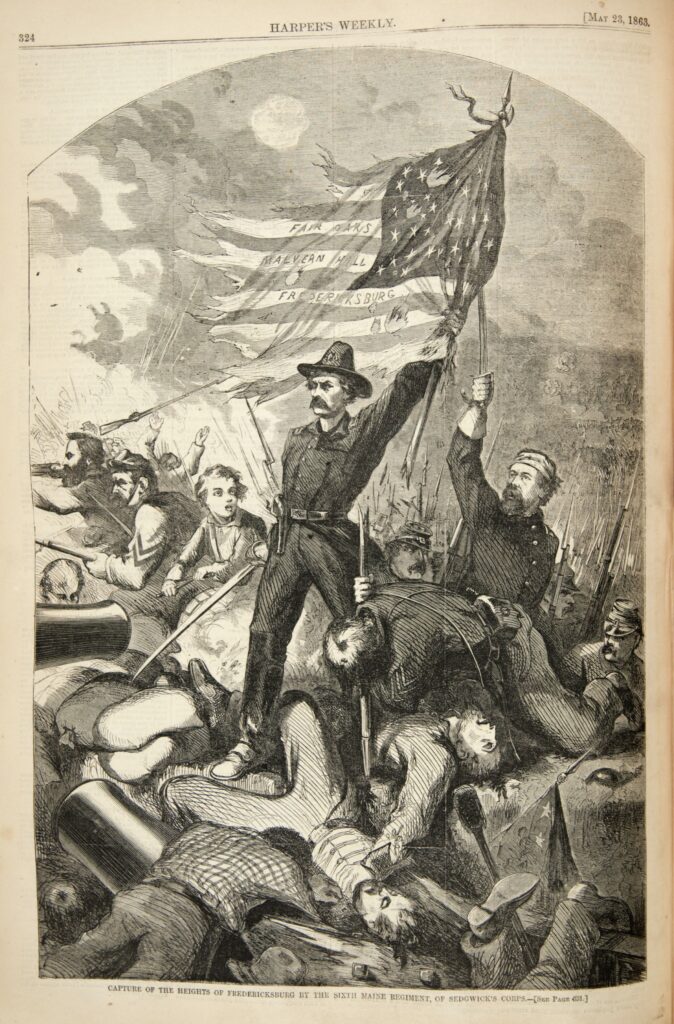

In this context, Church’s work does not seem entirely different from the mass-produced flag images in this section. “Capture of the Heights of Fredericksburg” was one of many illustrations to feature a tattered U.S. flag waving triumphantly over the scene of a battle. In a time before recorded music, sheet music, such as The Bonnie Flag, was another popular source for the ubiquitous icon. Finally, the flag appears in a more intimate context: the stationery on which a Union soldier, George Deal, wrote to his wife, Sarah. His photographic portrait appears later in this collection.

Selection: George Deal to Sarah Deal (November 9, 1862)

Questions to Consider

- Describe what you see in Church’s painting, Our Banner in the Sky. What is the scene that Church portrays? Why do you think he formed this national symbol out of a representation of nature? How would the meaning of the painting change if the Stars and Stripes appeared on a manmade flag and flagstaff?

- How does Church’s painting respond to the attack on Fort Sumter? What feelings does the painting evoke now or might it have evoked in viewers at the time?

- Examine the Harper’s representation of the capture of Fredericksburg, Virginia, a town that the Union had lost six months earlier in a crushing defeat. Would you describe this illustration as a realistic or symbolic representation of the battle? Why? What is the place of the flag within the image’s composition, or arrangement of figures? What message do you think this image conveyed to its audience in the North?

- Consider the illustrations on the cover of The Bonnie Flag and the letter from George Deal. What does the image of the flag convey in each of these contexts? Why do you think flags were so ubiquitous in the North during the war years?

War Photography

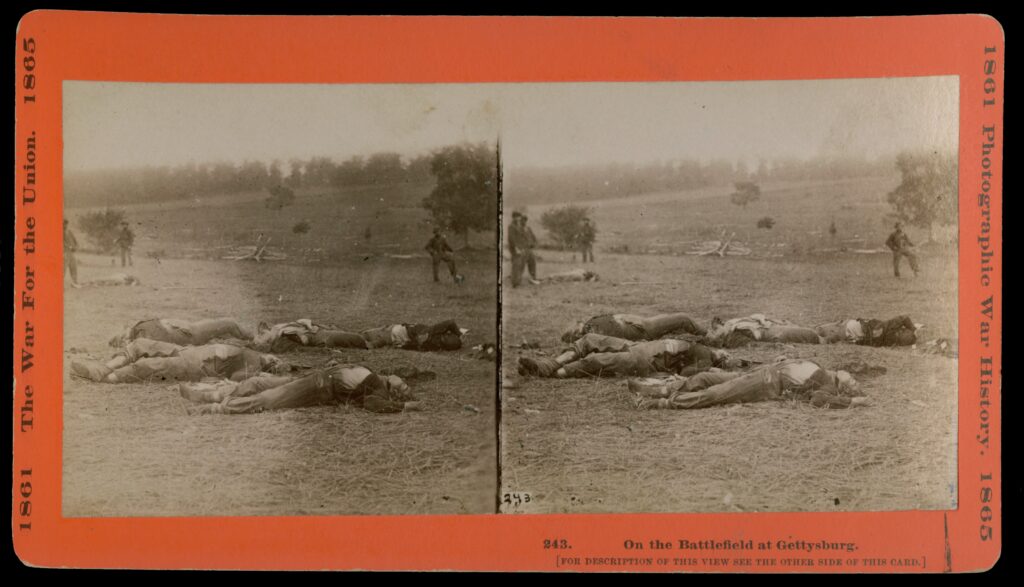

In the 1860s, photography was still a challenging medium, especially for reportage: the equipment was heavy and bulky, subjects had to be perfectly still when the camera’s shutter snapped, and processing images required mixing dangerous chemicals by hand. Yet photographers such as Matthew Brady and Timothy O’Sullivan ventured into the field to make the Civil War the first war to be extensively documented through photographs. The stark realism of corpse-strewn fields shown in photographs such as the one below seemed to many viewers to capture the particular brutality of this war. Although photographs were still too difficult to reproduce to be used in mass circulation newspapers or magazines, people found innovative ways to exploit the medium’s realism. The stereograph shown below presents two copies of the same photograph, slightly offset, which creates the effect of a three-dimensional image when seen through a handheld viewer. It portrays the aftermath of fighting in Gettysburg in 1863, one of the bloodiest battles of the war and the site of a major Union victory.

The war spurred the development of a thriving photographic portrait industry in cities and towns throughout the North. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers had portraits made as mementos for those they left behind. This photograph portrays Private George Deal whose letter to his wife, Sarah, appears in the preceding section. The negative was printed backwards; the U.S. on Deal’s uniform appears in reverse. Deal was killed at the Battle of Atlanta in 1864.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the stereograph of the Gettysburg battlefield. What does this image convey about the war and the lives and deaths of soldiers who fought? How does it compare to the illustrations of the war that appeared in magazines?

- Describe George Deal’s dress and posture in this portrait. What does the image tell you about how Deal wanted to be remembered? How does this image compare to pictures that people share with friends and family today?

Coming Home

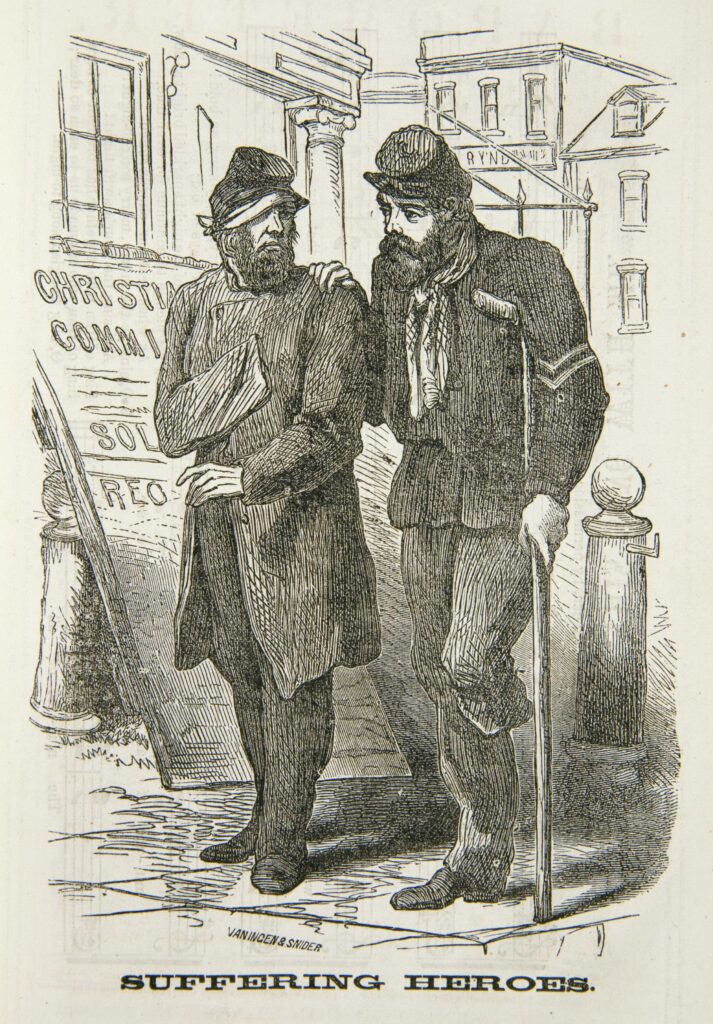

After the war’s end, many women and children at home adjusted either to the loss or to the return of their husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers with serious wounds or trauma. Soldiers returned home missing legs or arms or eyes. Depictions of the end of the war celebrated soldiers’ homecomings, but often did so in a way that communicated profound loss, evoking the soldiers who would not return home or the permanent scars of those who did. The images in this section appeared in popular periodicals during and just after the war’s final months.

Questions to Consider

- What do these images suggest about the reintegration of veterans into civilian life? Will they be embraced or honored by those who stayed home? How do the two figures in each image relate to each other?

- Examine Homer’s “Our Watering Places.” Does the image suggest changes in gender roles as a result of the war? How does it do so?

Images of the War

These images are examples of illustrations and photographs that captured scenes of the war, depicting violent battles, the mundane, and various other aspects of soldiers’ experiences.

The Homefront and Coming Home

These illustrations speak to the ways that the war changed the everyday lives of civilians in the North and depict how, after the war’s end, many women and children at home had to cope with the loss of loved ones or the return of their sons, fathers, husbands, and brothers with significant physical and psychological wounds.

Patriotic Iconography

These images offer a glimpse into the mass production and popularity of patriotic illustrations with representations of the U.S. flag in the North during the Civil War.

Further Reading

Brownlee, Peter John and Daniel Greene, curators. Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North. Exhibition co-organized by the Newberry Library and the Terra Foundation for American Art. 2013.

Burns, Sarah and Daniel Greene. “The Home at War, the War at Home: The Visual Culture of the Northern Home Front” in Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). 1–11.

Burns, Sarah and Daniel Greene. “The Toys of War.” New York Times (February 27, 2014).

Goodheart, Adam. “Foreward: Picturing War” in Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). xv-xx.

Gugliotta, Guy. “New Estimate Raises Civil War Death Toll.” New York Times (April 2, 2012).

Terra Foundation for American Art. The Civil War in Art: Teaching and Learning through Chicago Collections. 2012.