Introduction

Although it may seem obvious, “America” is very difficult to define—geographically, culturally, and historically. The notion of American art is similarly hard to define. Certainly, “American-ness” is something that needs to be discussed and arrived at rather than delivered as something fixed. Even so, it is possible to ask meaningful questions and to speak clearly about the history and appearance of American artworks. [The items highlighted here are limited to the continental United States, but many of the ideas discussed can be applied to an expanded definition of the Americas—i.e., the entire North American continent]

“Visual Culture” is a relatively new field that investigates not just works of “fine art” (paintings, sculptures, etc.), but also popular and ephemeral visual artifacts of all kinds, such as posters, stamps, t-shirts, currency, comic books and more. Visual Culture believes these objects to be just as important as traditional artworks in describing and reflecting a broad range of cultures and histories. Artifacts from American visual culture are not just seen in museums; collections like the Newberry’s house important primary documents that reflect the scope, history, and issues related to art produced in this country. At the Newberry visitors can also see a wealth of prints, maps, photographs, paintings, and sculptures on the walls and in its exhibitions. Encountering real objects—whether paintings, postcards, and even books—is important in fully understanding them.

American art has always had a vital and interested relationship with world art. American art borrows the look and subjects of the art of other nations, especially those in Western Europe. For instance, Southwestern and Mexican art was inspired by Spanish religious art; colonial portraits from New England resemble those by English court painters; American modernist artworks were inspired by avant-garde French and German art. This kind of appropriation is not uncommon, especially in such a relatively young country like America. Until about the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were no museums, no art schools, and no professional artists. In the next century, these conditions were rectified, but American artists were still enthralled by European and Asian art. On the other hand, more popular forms of creative expression such as quilting, carving, pottery, furniture, and all kinds of self-taught art have always flourished. They too intimately reflect this country’s unique experience and inherent diversity of ethnic background, class distinctions, and cultural expression.

During much of the history of this country, the government has funded the arts in only minor and sporadic ways (e.g., purchasing artworks to decorate government buildings). At other times, however, as during the Great [worldwide] Depression of the 1930s, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration directly supported artists across the country in programs like the Federal Art Project/Works Progress Administration. Artists were paid a monthly stipend for producing paintings, sculptures, murals, posters, and prints. In times of war, the government—like most governments around the world—enlists the arts for propaganda messaging and morale boosting. In the middle of the twentieth century, government entities like the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) supported competitive art projects. However, these came under attack by conservative politicians during the so-called “Culture Wars” of the 1980s. Today, artists also look toward city, county, and state monies to sponsor artistic projects (e.g., neighborhood mural projects). Still, most American artists have trouble finding any governmental aid for their work. The question of which public art represents American values is often contested, even more so in the twenty-first century. Sculptures of Christopher Columbus and of Civil War leaders, for instance, have recently inspired impassioned protests as Americans reconsider the kinds of histories they represent.

Essential Questions:

- Besides oil paintings and sculptures of what does American art consist?

- How have Native Americans been treated in American art?

- How does a painted portrait function? What is the transaction like between artist and sitter?

- What kinds of images, and in what form, have been produced for the public?

- What subjects have artists taken up in times of war?

- How have galleries and exhibitions exposed Americans to modern art? How would you characterize that art?

- How can publications reflect American art?

Imagery of Indigenous Peoples: The First Americans

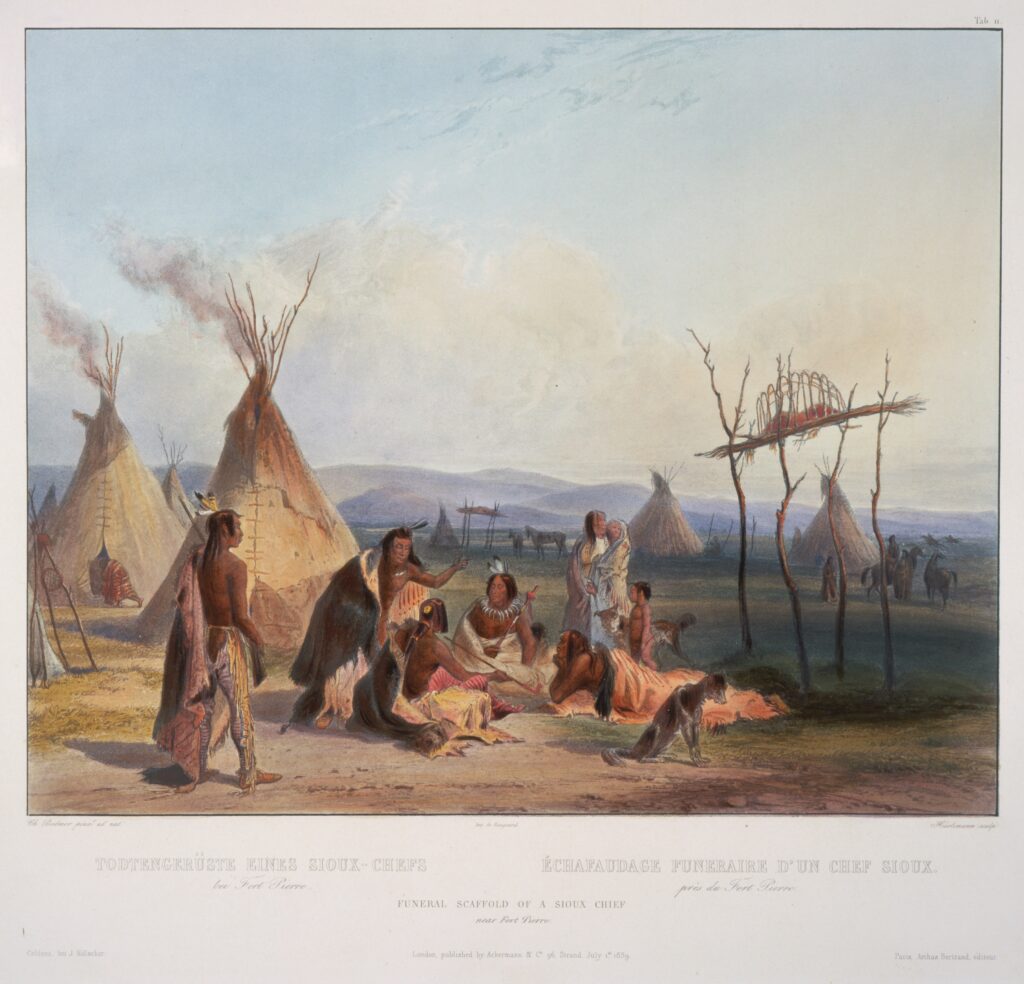

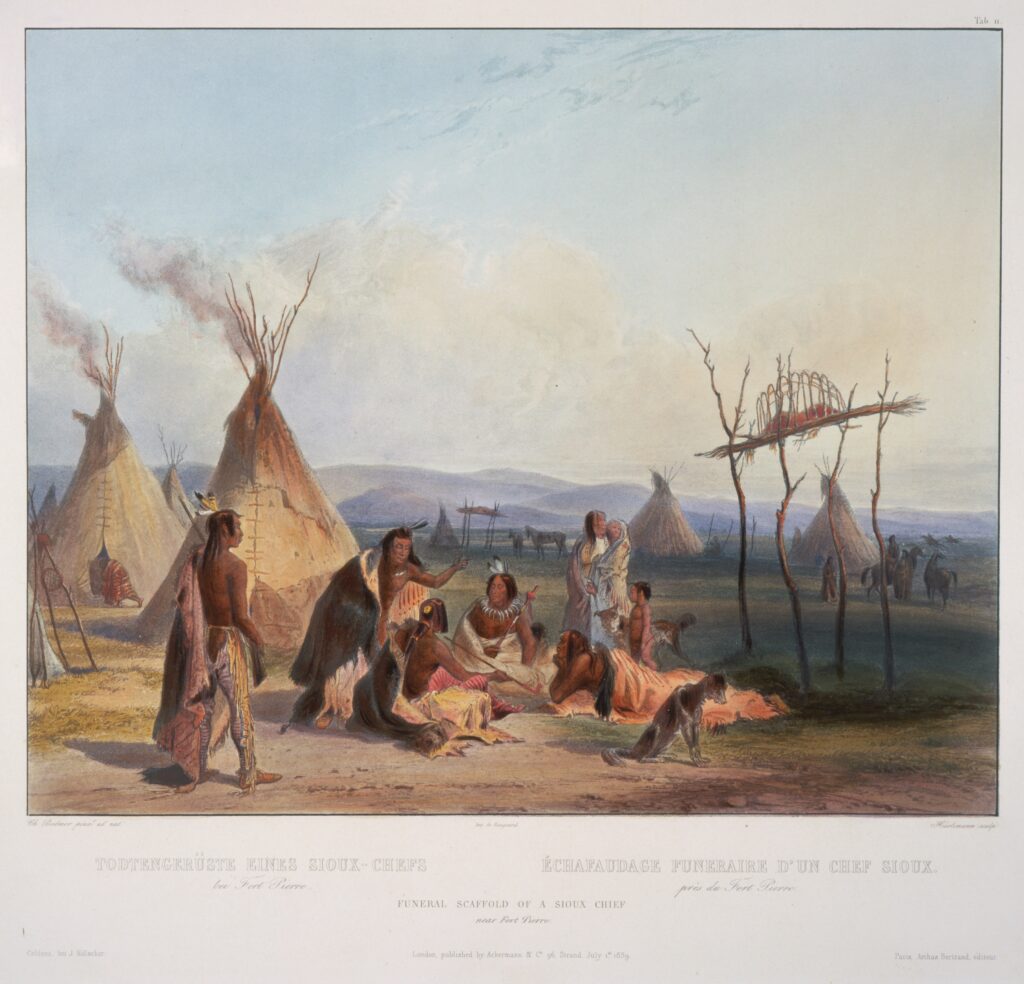

Before the age of photography, artists were called on to provide images of new geographical, cultural, and scientific discoveries. Commissioned by a European prince, the Swiss-born Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) made pictures recording his travels in North America. The hand-colored engraving illustrated here is based on a sketch the artist drew during an 1834 journey along the Missouri River, in South Dakota. As part of their funeral practices, the Sioux and other Plains tribes made scaffolds to support the corpse of a tribe member. Bodmer’s images of Native Americans are an early—and for the most part accurate and sympathetic—source of information about indigenous peoples and their cultures. Other American artists who painted Native Americans include George Catlin (1796-1872), who depicted the Plains tribes, and later, Henry Farny (1847-1916) and Walter Ufer (1876-1936), who captured the peoples of the Southwest.

The first images of indigenous peoples in American art reflect a desire to record visual information. Later images, made when they were more disempowered and being moved to reservations, tended to show them more reverentially and with a desire to beautify. For instance, in the 1890s, the painter Elbridge A. Burbank was commissioned by his wealthy uncle, Edward F. Ayer—a Chicago business man who collected books and items related to indigenous cultures—to make portraits of Native Americans. Burbank spent two decades traveling throughout the American West, creating portraits of members of more than a hundred tribes. His Portrait of Gi-aum-e Hon-o-me-tah shows a young Kiowa woman in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Burbank’s pictures are notable for both their realistic and their humane qualities. He wished viewers to see the real person behind the different costumes and settings. This is atypical and admirable since many American artists often relied on stereotypes when making pictures of people of color. To view additional collections with artwork depicting American Indians, visit Art of Conflict: Portraying American Indians, 1850-1900 and Indians in the Archives.

Questions to Consider:

- How are the Native Americans treated in the artworks seen here?

- What are the differences in the way Native Americans are depicted between the pictures by Bodmer and Burbank?

- Which details in each do you think would be interesting to people looking at them at the time they were made? Which details are interesting to you? Why?

Nineteenth-Century Portraiture: George P. A. Healy

Many of the artworks produced in America, particularly before 1900, were portraits, and many of the most renowned artists in this country have been portraitists. Portraits were expensive, and having one was a symbol of one’s status. It has been said that Americans have always been obsessed with pictures of themselves. This is especially true of photographs, which have been predominately of people. This self-picturing continues today in our fascination with camera “selfies,” and in the many social media platforms for instantly posting photographs.

George P. A. Healy (1813-1894) was one of the first professional painters in Chicago; by the 1870s he had become one of the most important portraitists in the country. Renowned politicians, celebrities, church figures, and wealthy people all “commissioned” (ordered from him) and “sat” (posed) for his pictures. Like all successful portraitists, Healy produced images that made his sitters look dignified and attractive. After all, the patron buying the picture can rightfully demand that they be portrayed in any way they choose. Here, Baroness De Pierre and her daughter are shown as particularly pretty and feminine in their elegant clothes and graceful poses. The Baroness was a family friend of the artist; she married a French nobleman, lived in Paris, and was a member of the royal court.

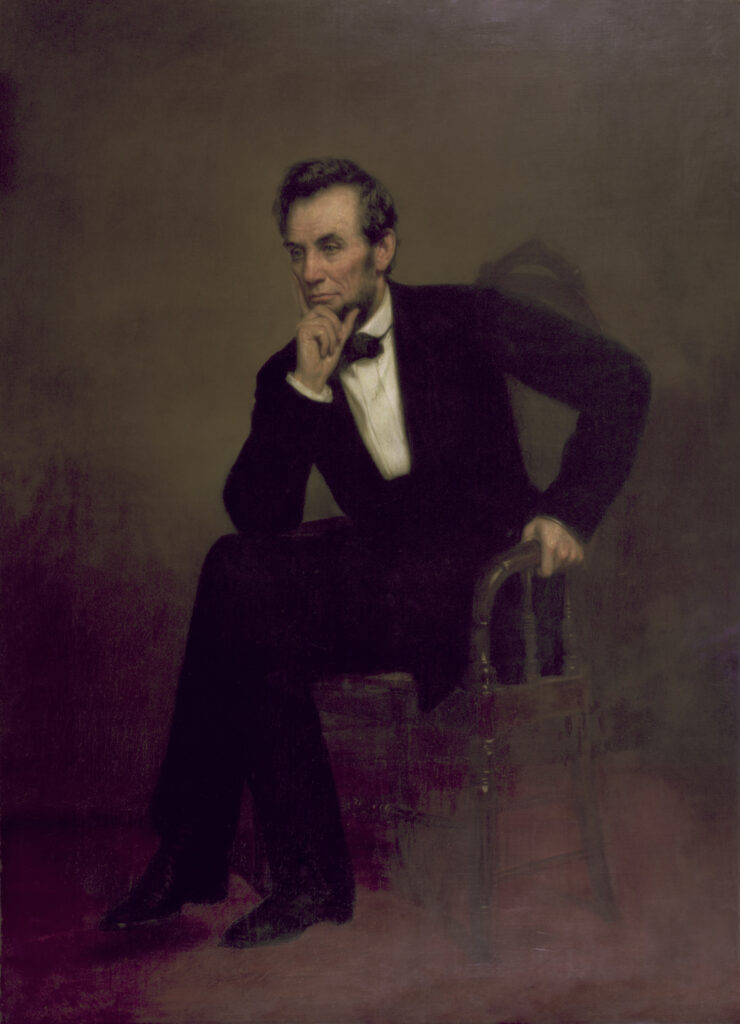

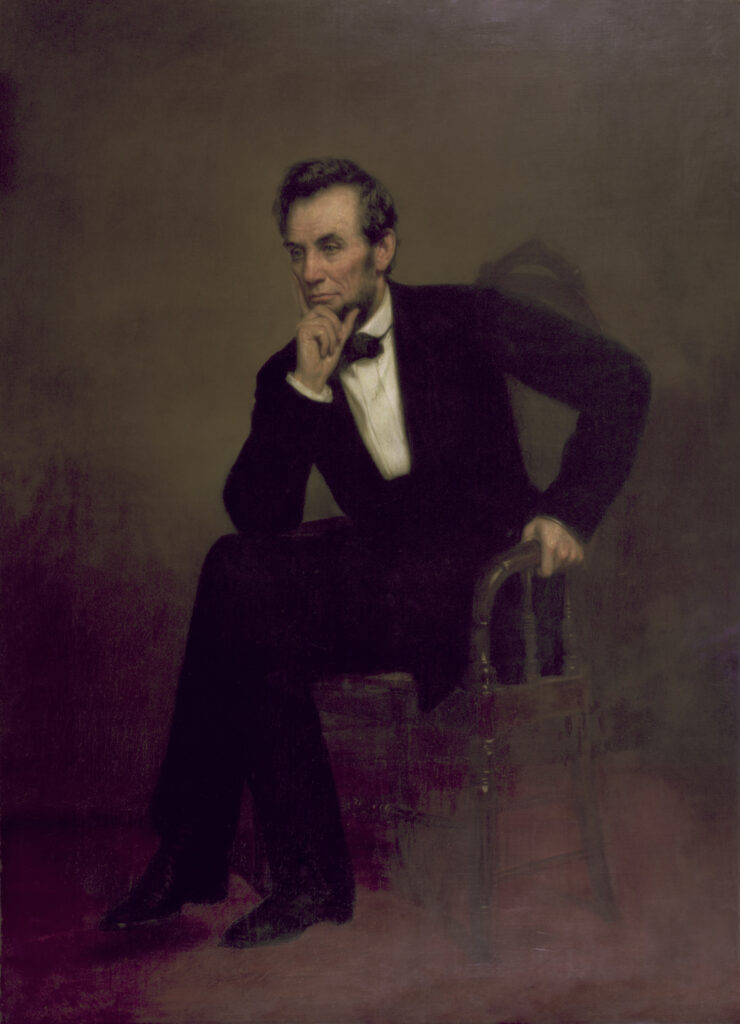

It has been said that Americans, as citizens of a relatively young country, are quick to document and memorialize its heroes. Indeed, much American art celebrates the leaders and heroes of this nation’s history. This was especially true of Lincoln, who was assassinated just at the end of the Civil War; he was the first American President to be murdered in office. Accordingly, there was a great demand for artworks and monuments of all types devoted to him. As the first American president to be extensively photographed, artists used photos to accurately model their imagery of him. Sculptures of the 16th President are the most conspicuous, such as the colossal Daniel Chester French seated Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial (1920) or Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Lincoln: The Man (1887) in Chicago’s Lincoln Park.

To make this portrait of Lincoln, Healy copied him from his own painting entitled The Peacemakers of the same year. [Viewers from the defeated Confederate states might have disagreed with that title!] The Peacemakers shows Generals Ulysses S. Grant—the Newberry also owns an 1868 Healy portrait of him alone, taken from The Peacemakers, as well—William Tecumseh Sherman, and Admiral David D. Porter discussing the end of the Civil War aboard the steamship River Queen. It currently hangs in the White House. People remembered that Lincoln frequently assumed this pose; he was a superb listener. Healy made three other copies of this painting, reminding us that professional artists in the nineteenth century frequently produced copies from their own works in order to satisfy demand for their art.

The Newberry Library owns many of Healy’s portraits, and they can be seen today hanging throughout the building. His portrait of Lincoln, and nearly all of his many portraits in the Newberry were given to the library by Healy himself. Artists frequently take an active role in placing their artworks in public venues where they can be appreciated and cared for.

Questions to Consider:

- What was it like to be a portrait painter in the nineteenth-century?

- How has Healy expressed the social class and personalities of his sitters in Madame de Pierre and Her Daughter?

- Do you agree that Americans are especially interested in making artworks and monuments to their leaders?

Popular Art: Imagery for the People

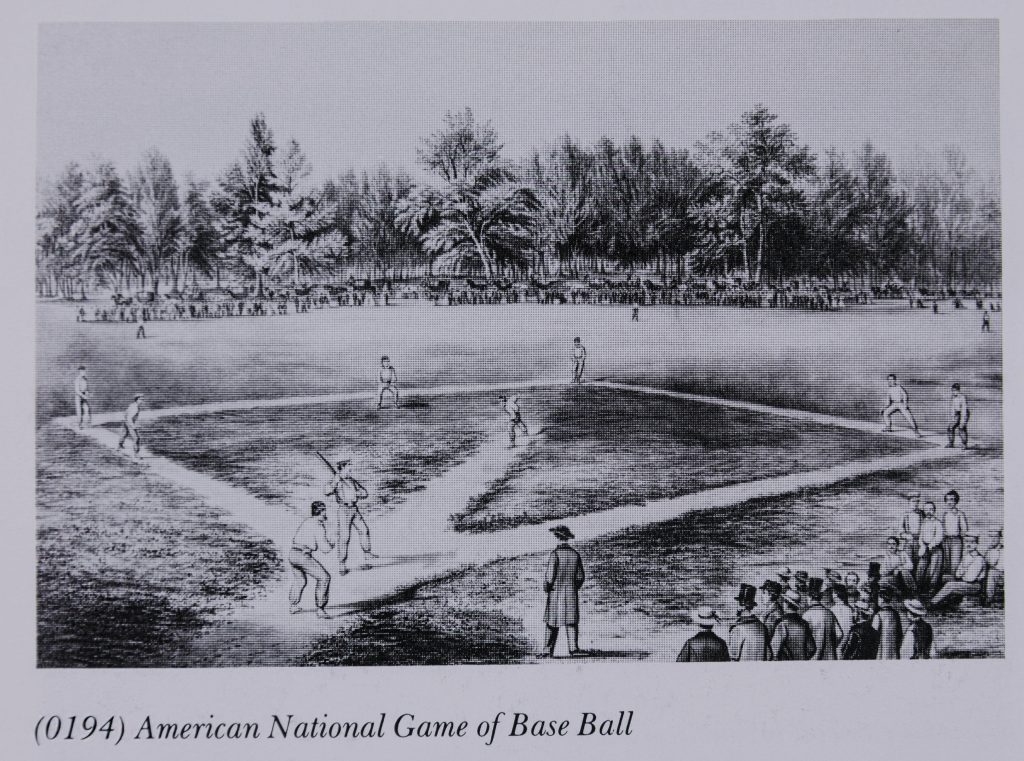

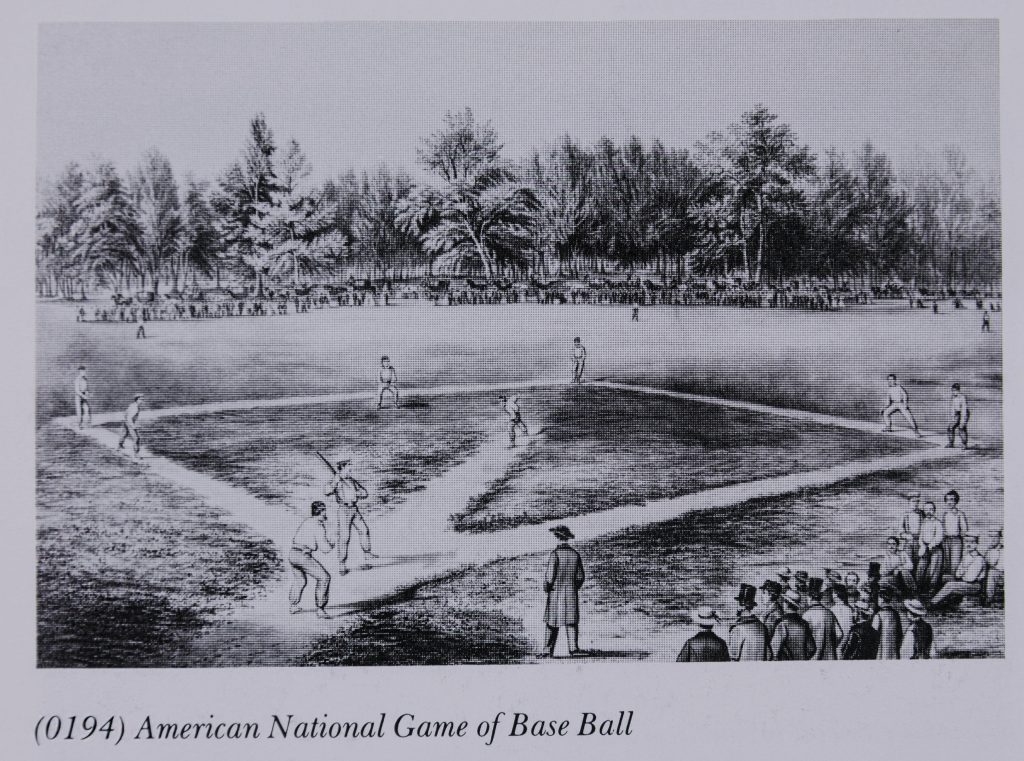

In the middle of the nineteenth-century, lithography was a relatively new, efficient medium to reproduce prints for a mass audience. Making one involved drawing with a grease crayon on a polished limestone. Lithographs could be printed in books and magazines, and could be framed and hung. New York partners Nathaniel Currier (1813-1888) and James Ives (1824-1895) hired artists to make pictures of American landscapes and cities, famous events, political subjects, animals, and scenes of everyday life. They were then hand colored, often by young women who worked at tables, and who each colored a certain part of the image. Currier and Ives prints were cheap and extremely popular; nearly every home had one on display. Together they make up a vivid picture of nineteenth-century America, and how audiences saw their world. A catalogue raisonné is a book that includes all known artworks by a certain artist (or in this case, a partnership). The Currier and Ives print shown here is entitled “The American national game of base ball” (c. 1866). Although it grew out of older games involving batting and running, baseball was a relatively new game at the time this picture was made.

Sometimes an artwork is so well loved it acquires an enormous popularity, and is reproduced to satisfy the demand for it. Jules Breton’s painting Song of the Lark depicts a farm girl who pauses on her way to work to listen to a beautiful bird song. It was consistently voted the favorite painting in the Art Institute for decades. Viewers were moved by the humble subject—it inspired Midwestern author Willa Cather’s novel of the same name–and were dazzled by the striking realism of the painting. Even though the subject and landscape are French, Chicagoans from many different social classes identified with it. Because they were produced in great numbers and were mailed, postcards are regarded as important components of American visual culture. They enable people to share their experience of a piece. Postcards also extend the exposure of a single, unique artwork that resides in a museum.

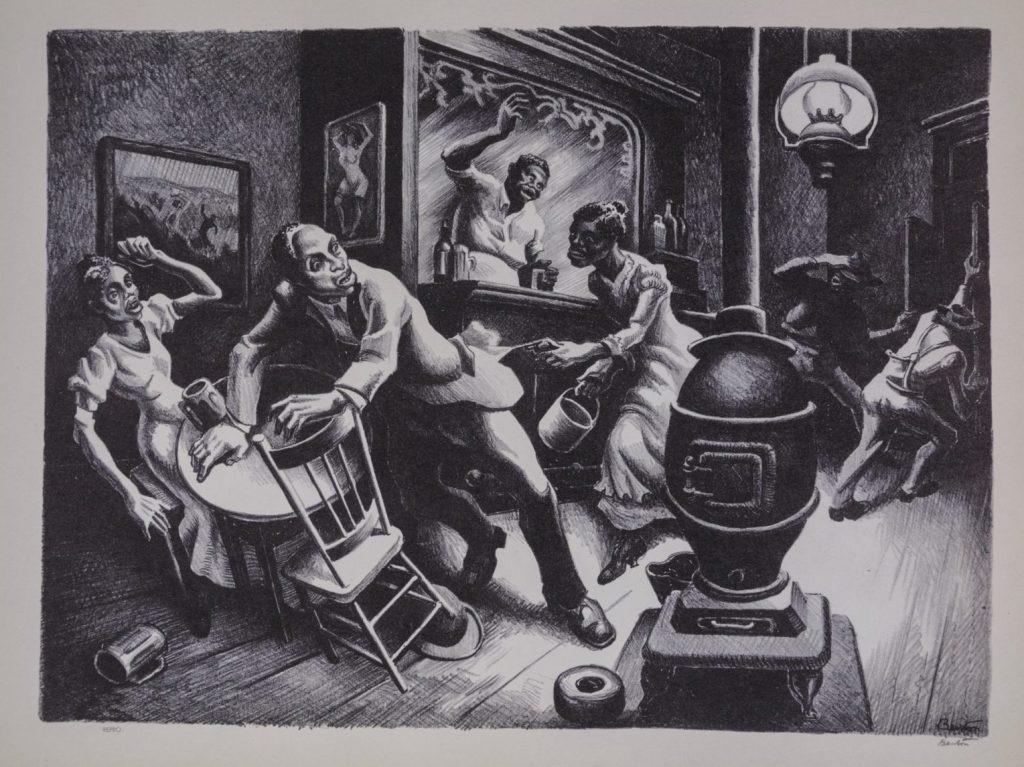

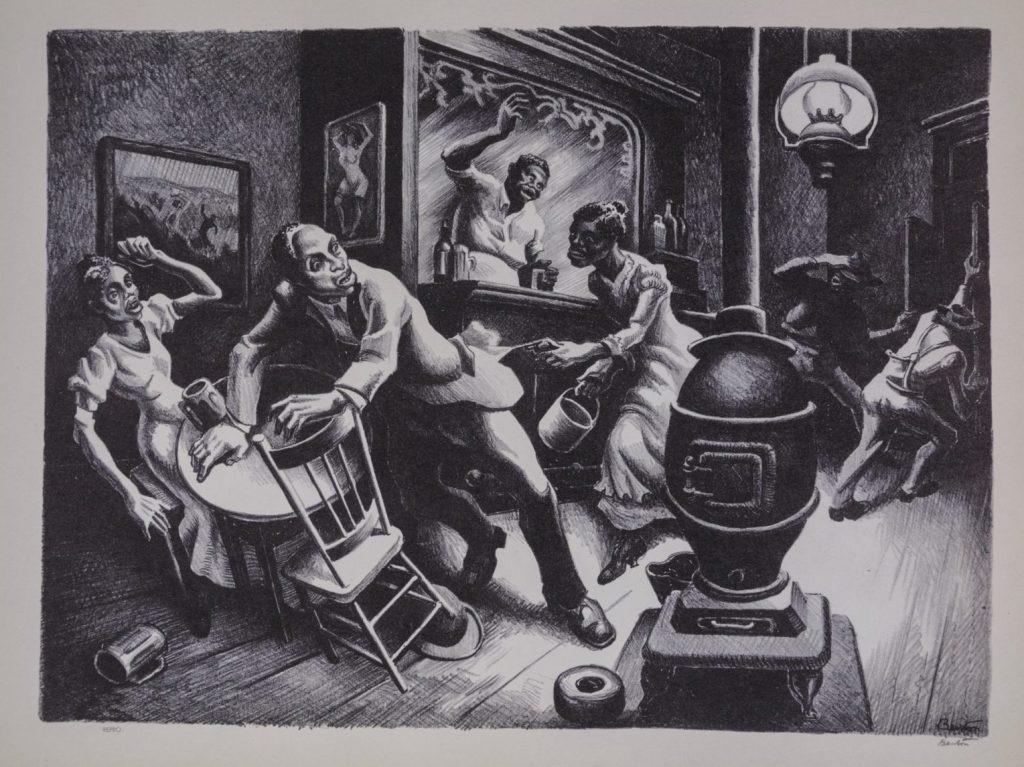

Not just artists, but audiences—including critics and journalists—are important in determining which American art is celebrated and which is not. Thomas Craven was a powerful, conservative art critic in the 1930s; he championed artists like Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry as “Regionalists.” These artists depicted the landscape and lore of the Midwest, which had not often been visualized in art. Like Craven, Benton was interested in finding specifically “American” subjects. His lithograph, I Got a Gal on Sourwood Mountain shows a country dance; the picture’s title is taken from a popular song of the time. Benton adopted a simple and rustic style that resembled unsophisticated American “folk art” and which avoided the look of European and/or modern art.

Questions to Consider:

- Are there any equivalents today of Currier and Ives prints—any images, in any medium, that reflect popular culture and everyday life?

- Why do you think Breton’s painting Song of the Lark was so popular?

- Why were the “Regionalists” called so?

Expressing Conflict: War and American Art

American art has responded in varying degrees to the nation’s wars. Some images have explicitly visualized the conflict, while others have been less direct in their references. Artists have been employed by the government to make patriotic imagery, while others work more privately, expressing their own views about the conduct, consequences, and meaning of the war. In this American art has not been so different than that of other western, developed countries. But distinct from autocratic governments and dictatorships, the American government has never outlawed any particular style or subject. Overall, American art provides the record of a creative response to the history-defining struggles this nation has endured.

Frederic Church made Our Banner in the Sky in the opening year of the wrenching American Civil War (1861-1865), a conflict about the future of slavery. The artist projects the northern flag of the Republic onto the twilight sky, the banner composed wholly of natural elements—stars, clouds and a blasted tree that serves as a pole. This fantasy suggests that nature itself favors the success of the northern cause. The desire to see national destiny reflected in the outdoor world, it should be noted, is a very common tendency among viewers from any country. Church (1826-1900) was a painter linked to the early nineteenth-century Hudson River School, the first group of artists to depict specifically American landscapes. Having bought the copyright to Church’s painting, a New York publishing firm reproduced it as a lithograph, which became very popular. In an intriguing blending of media, the artist has painted over one of these to make the one we see here.

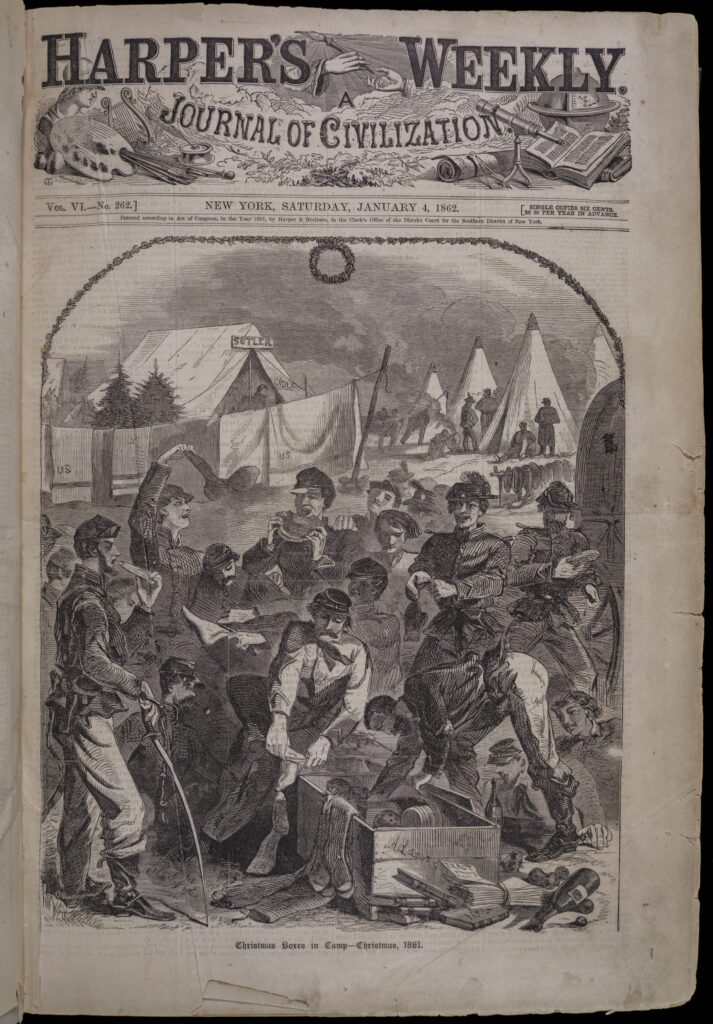

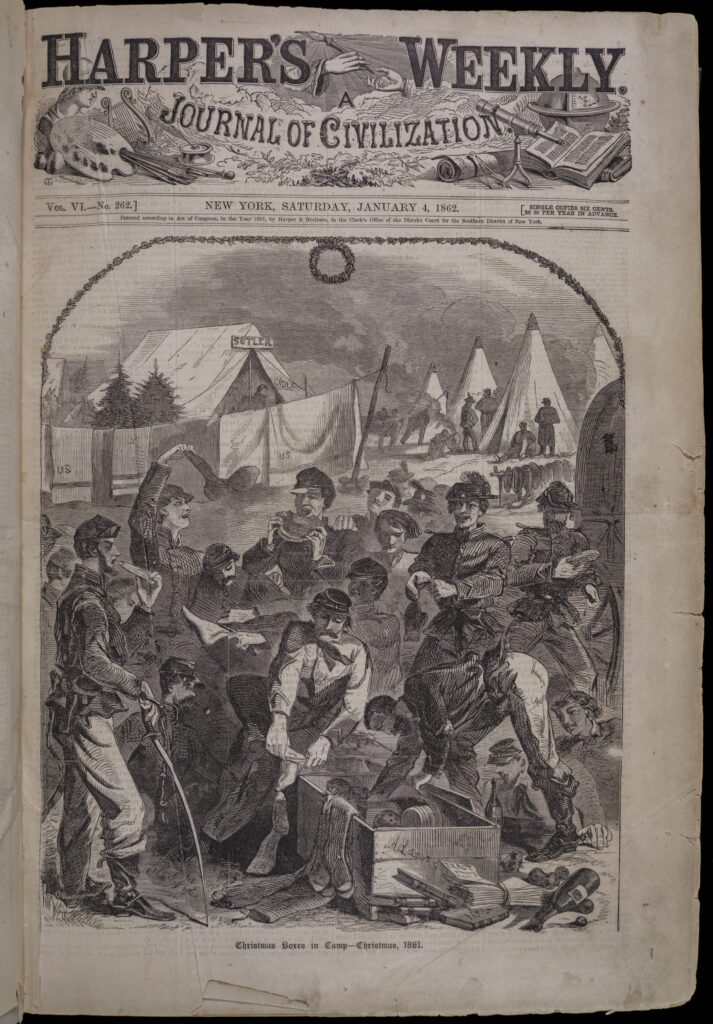

During American wars, artists have sometimes been sponsored by publications. They were asked to gather (visual) information, almost like modern-day journalists. Winslow Homer (1836-1910), an illustrator from Boston, was sent to the front to cover the northern Army and to send back drawings. These would then be turned into wood engravings and printed on the magazine’s pages. Embedded with the army, Homer captured daily life in the camp, something that would have greatly interested readers with family members serving. Christmas Boxes in Camp… shows soldiers receiving holiday gifts—essentials like socks and food—from home. In the decades after the Civil War, Homer became one of the most renowned painters in America.

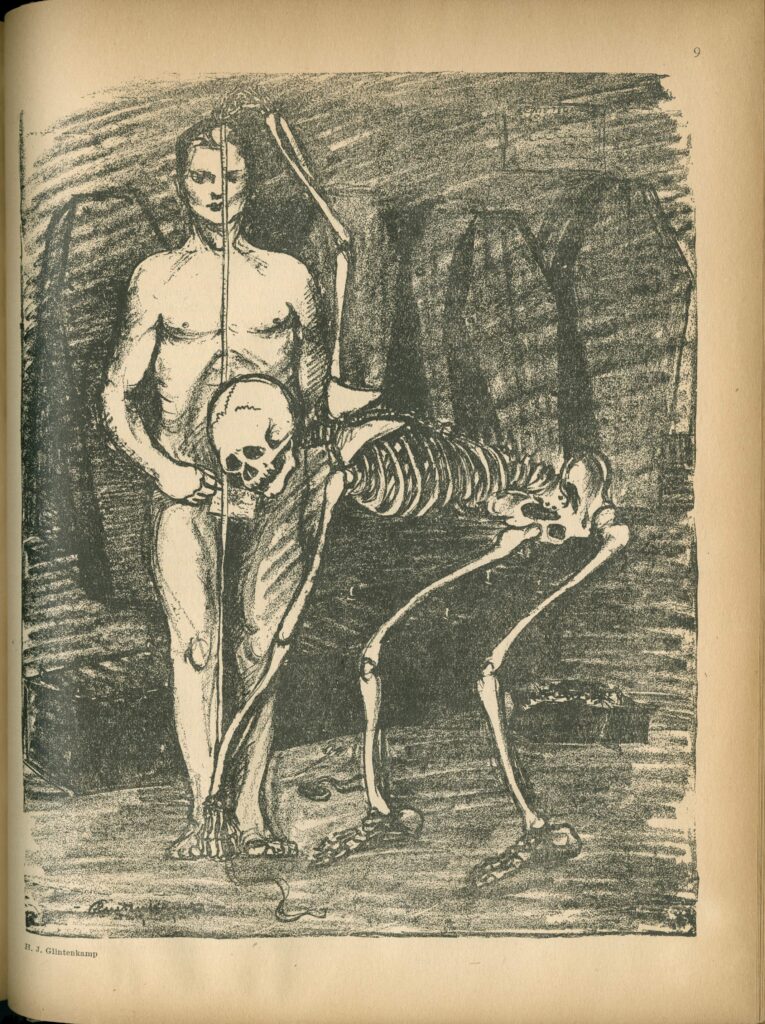

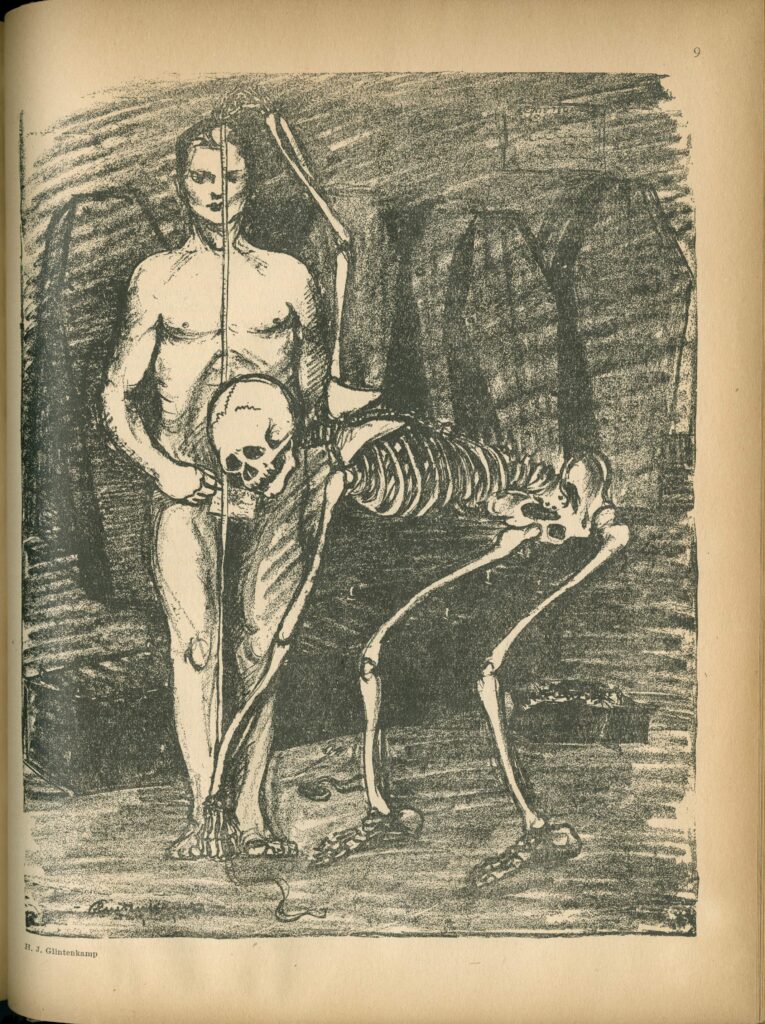

Not all artists have made such positive images during periods of conflict. Some have critiqued policies and practices in visual terms. Glintenkamp’s “Physically Fit,” for instance, suggests that American World War I troops had little chance of survival and were being unnecessarily sacrificed. The first global war, WWI was particularly brutal in terms of new kinds of weapons (poison gas, machine guns, tanks, etc.) and for the enormous casualty numbers. This image recalls the bitingly satirical drawings of George Grosz, a German artist who frequently attacked the military establishment in this same period.

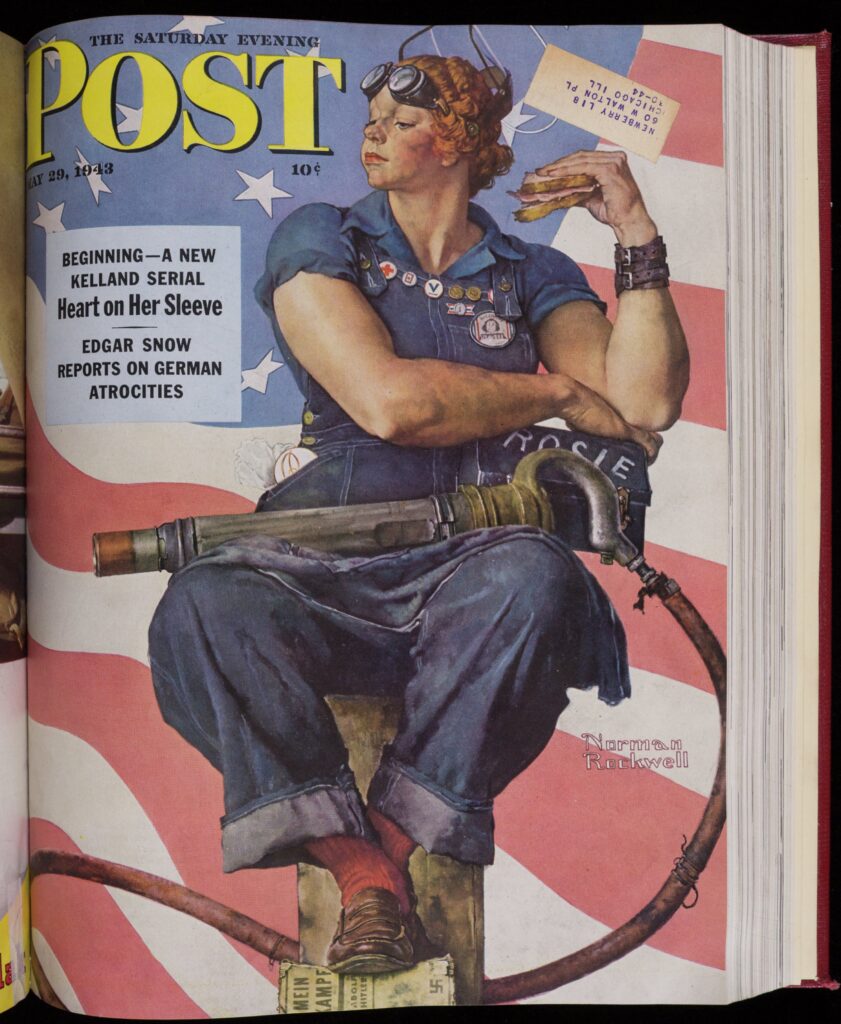

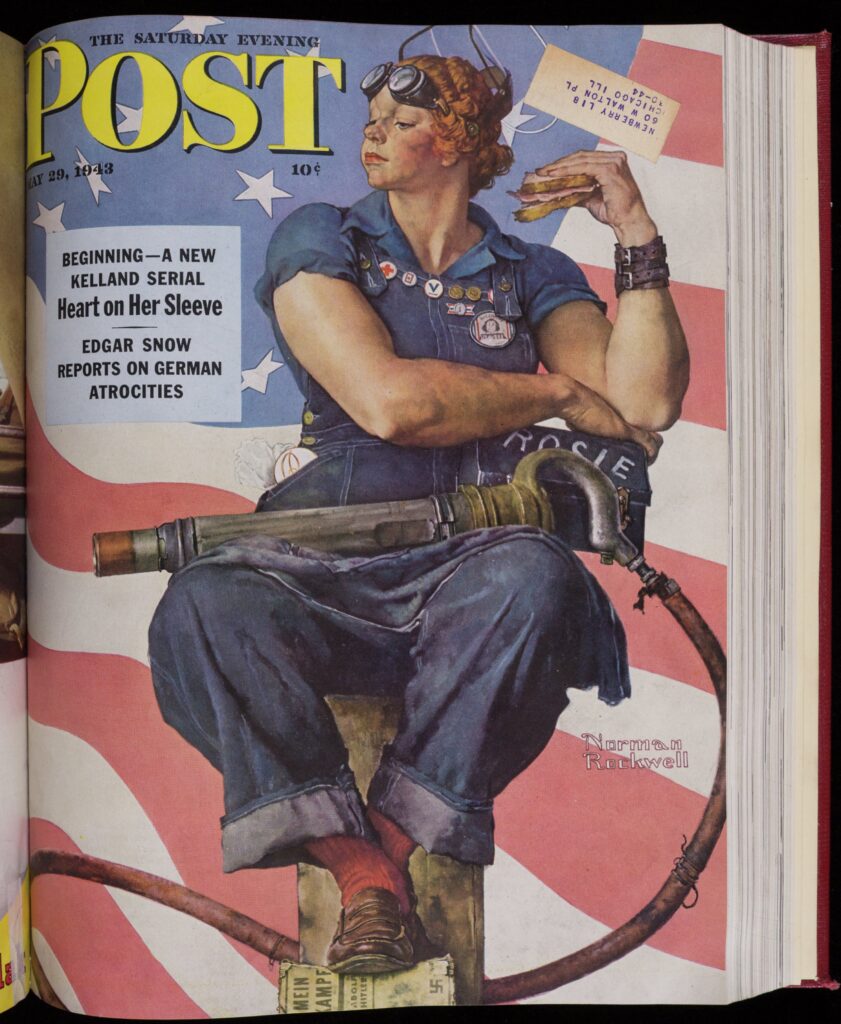

Of course, it was not just men who fought America’s wars; women also contributed in major ways. During World War II women went to work in factories, replacing the men serving in the military. Illustrator-artists like Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) visualized this new kind of workingwoman, now an indispensable member of the war effort on the “home front.” The home front was the war effort performed by the civilian population not directly engaged in fighting the enemy. Activities included the sale of war bonds, scrap and salvage drives, home gardens, rationing, and war-related manufacturing. Here Rockwell depicts Rosie the Riveter as strong (note her massive arms) but relatable (note her penny loafers) as she cradles her rivet gun in her lap and eats her lunch. She resembles Michelangelo’s famous Renaissance painting of the prophet Isaiah on the Sistine Ceiling, in Rome. Artists often borrow from famous art for their own work, adapting it to meet their own needs.

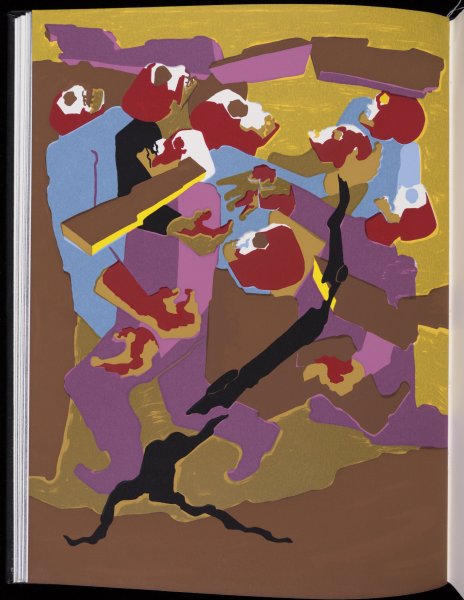

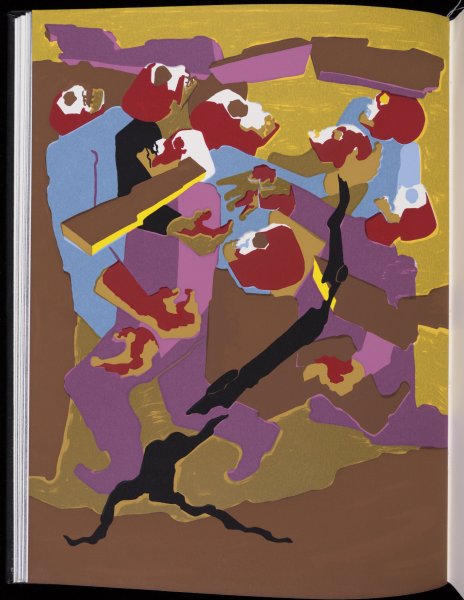

Sometimes original art is made specifically to be reproduced in a book. Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) a renowned twentieth-century, African American artist provided the screen prints for Hersey’s famous book about the destruction of the Japanese city of Hiroshima at the end of World War II (August 6, 1945). His style is jagged and abstract, befitting the horrors of the dropping of a nuclear bomb on a civilian, urban population. Artists tasked with illustrating a book face many challenges (e.g., which content to provide pictures for, in what style, in what medium, and so forth). The result in this case is a book of grim information enlivened by powerful artistic interpretations.

Questions to Consider:

- In Our Banner in the Sky, what makes up the flag one sees in the sky?

- What is the equivalent today of having an artist be on the front lines of battle to make pictures?

- In Glintenkamp’s picture what kinds of symbolism do you see?

- If you were an artist criticizing an aspect of America’s involvement in war, what style would you use to do so (realistic, abstract, etc.)?

Twentieth-Century American Art and Art History

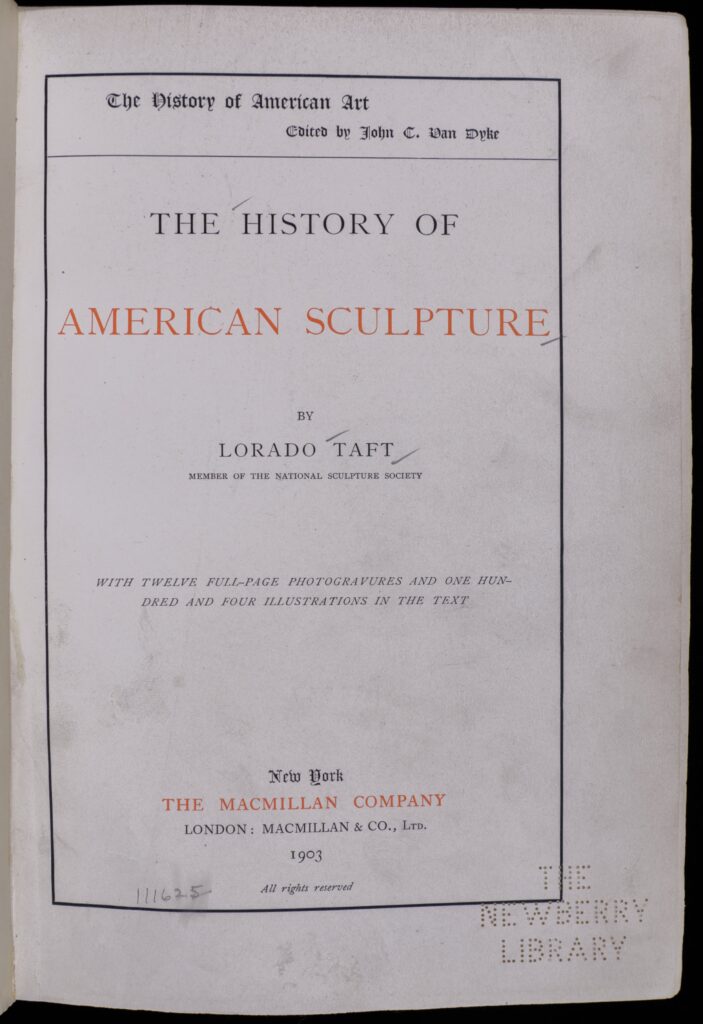

Lorado Taft (1860-1936) was perhaps the most renowned and important artist Chicago has ever produced. He was a professor of sculpture at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and at the University of Chicago; his Midway Studios still exist in Hyde Park. Taft was an integral part of the civic and professional art scene in this city in the period between the World’s Columbian Exposition and the 1930s. His ambitious sculptures and fountains are found throughout the city, and are an important aspect of the City Beautiful Movement in Chicago. Taft’s own work, like that of nearly every sculptor trained at the end of the nineteenth century, is figural, that is, it is comprised of the human body. His most well known Chicago works are the massive Fountain of Time (1922), situated at the end of the Midway Plaisance in Hyde Park, and the Fountain of the Great Lakes (1913), in the south courtyard of the Art Institute of Chicago. Taft was also an expert historian of sculpture, having personally known many of the American sculptors he wrote about. His comprehensive, profusely illustrated History of American Sculpture (1903), endured for more than six decades as the premier scholarly text on the topic.

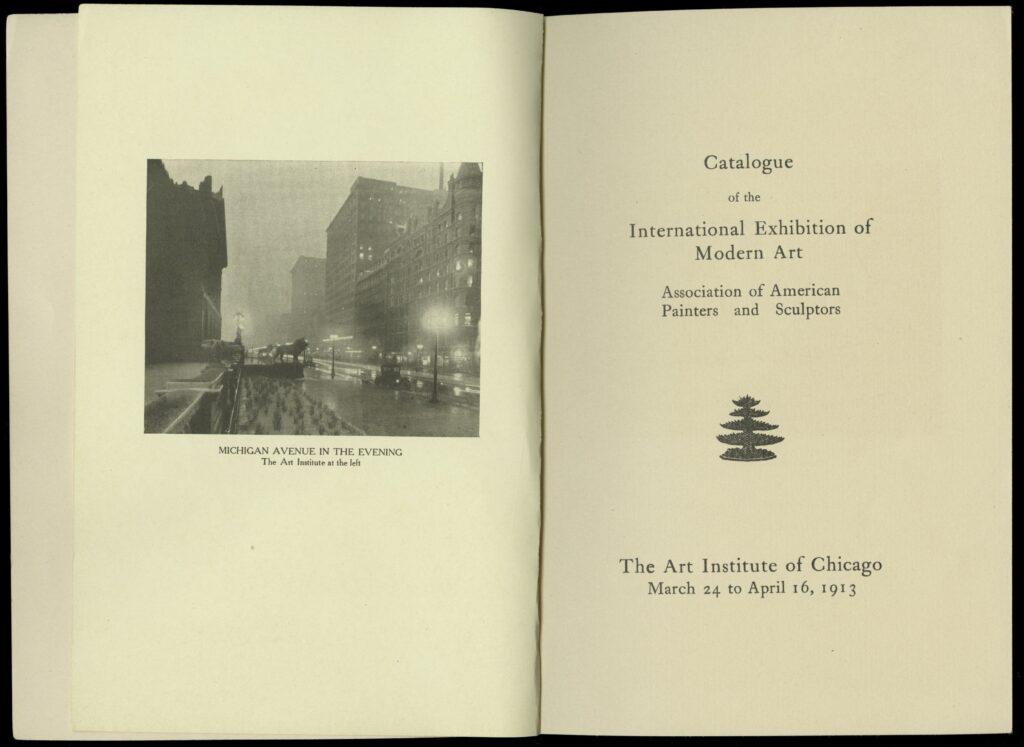

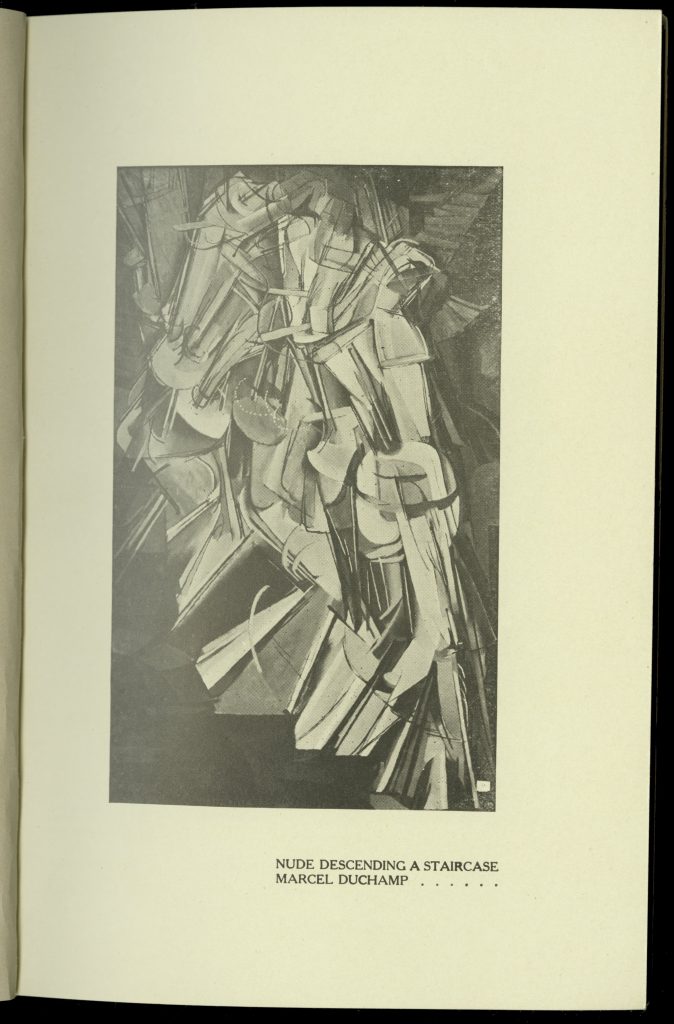

The story of American art also includes art exhibitions that changed the course of art history. The documents that accompany those events take on an importance of their own, such as catalogues like the one for the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art. Known popularly as the “Armory Show,” this exhibition introduced stunned American audiences to European modern art. Artist-organizers had gone to Europe to collect the artwork of modern artists; their hope was to make people more aware of recent trends in art. After opening in New York, the exhibition was then shown at the Art Institute of Chicago for more than a month before moving on to Boston. It included a vast array of European artworks, from the middle of the nineteenth century through those by the new French Cubists. It drew record crowds, and was heavily covered in the press. Many viewers came to scoff at the most recent art, especially Marcel Duchamp’s now-famous Nude Descending a Staircase, #2 (1912). Art students from the School of the Art Institute protested artists such as Henri Matisse on the museum’s steps. Although the Armory Show confused many people, others were dazzled and inspired by it. It is an example of how, in America, there are efforts to expose audiences to recent artistic developments. It also demonstrates how polarized have been the artistic tastes of Americans.

Selection: Art Institute of Chicago, Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Modern Art (1913).

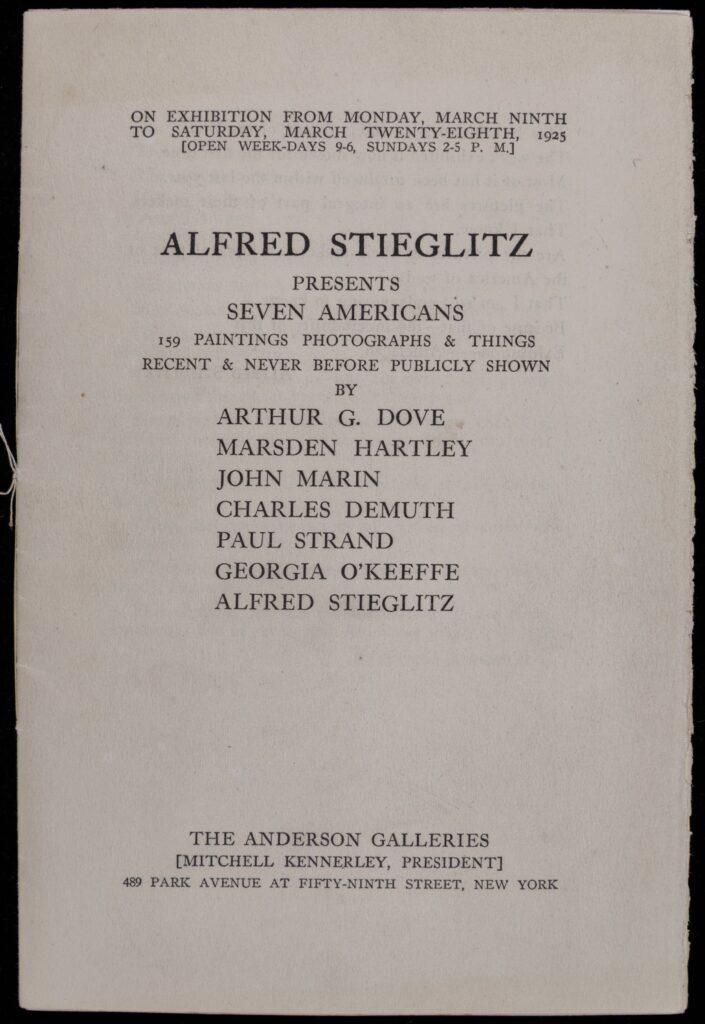

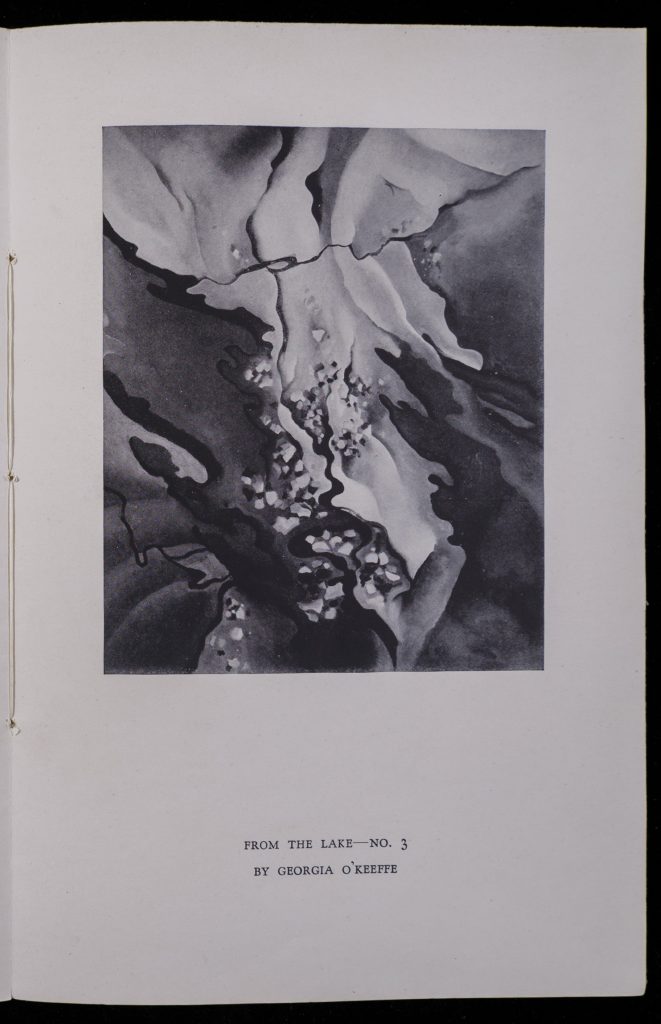

In the history of American art there sometimes appear charismatic, committed supporters who advance causes and create opportunities for artists. In the early years of the twentieth century Alfred Stieglitz was a crusading photographer who fought to have the medium recognized as a legitimate art. This was at a time when taking photographs was becoming very easy and very popular. Stieglitz was also a New York gallery owner who promoted the work of progressive artists who he felt had arrived at a new and specifically American type of art. Indeed, private art galleries in this country’s major cities have been important in showcasing new art. Many of the photographers and painters Stieglitz first supported in his Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession (or simply, “291,” its address on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue), are today regarded as important avant-garde artists. Several are featured in this exhibition, including Arthur B. Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Georgia O’Keeffe–-one of the most renowned American artists of all. Exhibition catalogues like this helped advertise the work of contemporary artists. They now serve to document the event, and in this case, Stieglitz’s efforts.

Selection: Alfred Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans: 159 Paintings Photographs & Things Recent and Never Before Publicly Shown (1925).

Questions to Consider:

- How is Taft important to Chicago? To the history of sculpture in America?

- In what ways did Stieglitz promote photography and art in America?

Art in/as Publication

“American art” does not simply mean the totality of paintings and sculptures made in this country. People have experienced art and the ideas and activities associated with it in many forms. By the twentieth century, books, magazines, and publications of all kinds made significant space for the arts. Nearly every item in this essay fits into this category. Examining them for the way they functioned as texts produced in certain communities (publishing house, art gallery, etc.) adds to our understanding of how they were understood. For instance, Harper’s Weekly, discussed above was the most widely read and influential magazine in America during the Civil War. Its combination of illustrations, news, and general interest content made it popular with male and female readers alike. The editors hired artists like Winslow Homer to produce pictures for it. Similarly, Norman Rockwell made paintings for many of the cover illustrations of the Saturday Evening Post, it being one of the most popular magazines of the mid-twentieth century. The Masses, too, where Glintenkamp’s anti-war images appeared, was a socialist magazine and featured the socially conscious work of important American artists, such as John Sloan (1871-1951). The Masses was published from 1911 until 1917, when the government brought charges against it for attempting to obstruct the draft (“Physically Fit” was a prime example). As we have seen here, other printed matter such as picture books of American artworks, catalogues raisonnés, exhibition catalogues, and illustrated histories of art should also be taken into account in any examination of how Americans have engaged art. Many of these publications have become renowned as aesthetic objects in their own right. Taft’s History of American Sculpture (1903), for instance, besides being the first comprehensive treatment of this subject, also functions as a veritable art gallery of American statues. Thomas Craven’s Treasury of American Prints was a picture book that could be found in middle-class living rooms and professional offices across the country. Books about art had a wide audience, and were a lucrative publishing category. Sometimes, however, books were closer to outright artworks.

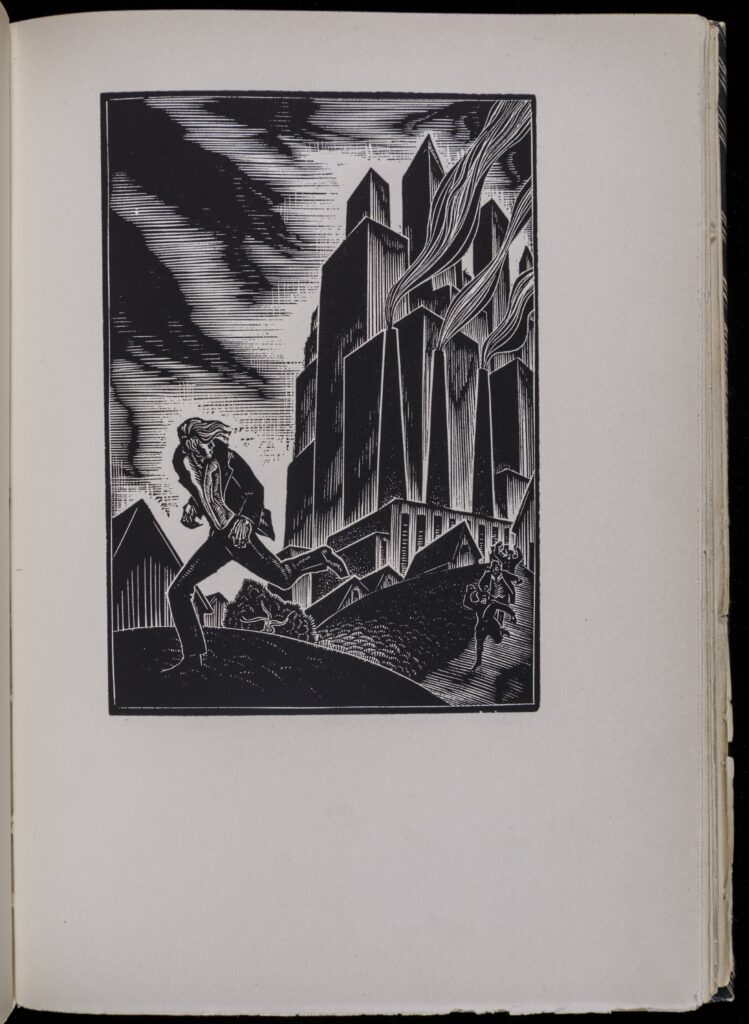

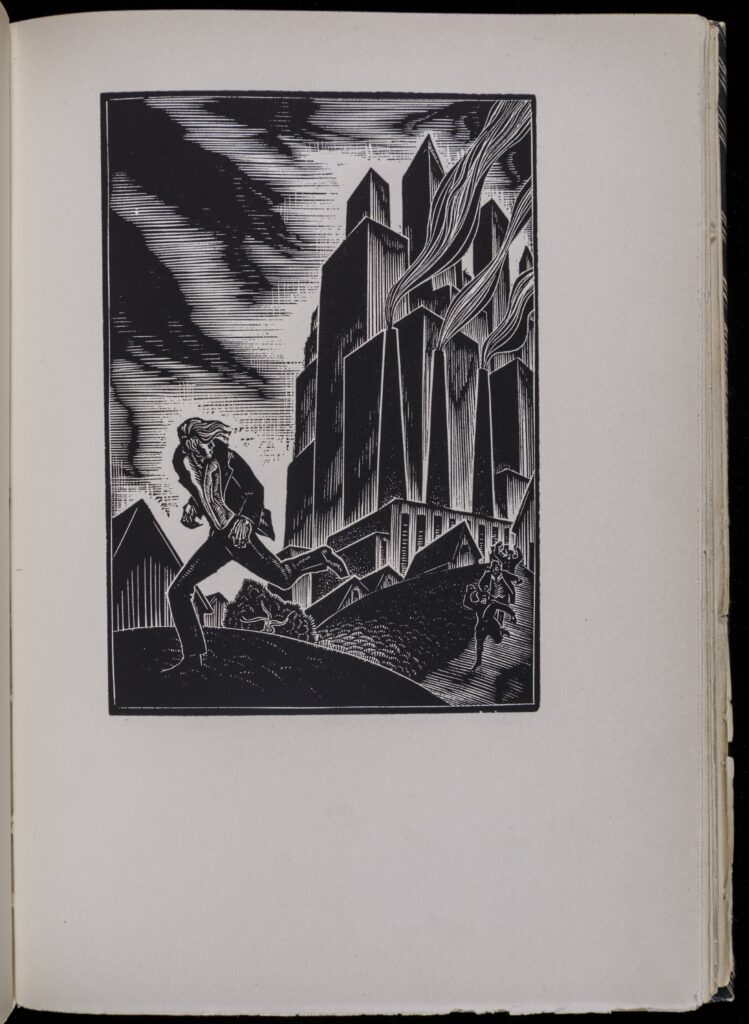

Lynd Ward was one of the pioneers of the graphic novel: a narrative of images without text, sometimes called a “wordless novel.” Gods’ Man was the first of its kind in America, though European artists like Frans Masereel and Otto Nückel had inspired artists everywhere with their own examples. Ward’s one hundred and thirty nine expressionistic, black-and-white woodcuts in God’s Man tell the story of an artist who sells his soul in return for magical creative abilities. Because there was no text to read, graphic novels could be enjoyed by everyone; the same is true of silent films in the early twentieth century. Graphic novels experienced a resurgence in America in the late twentieth century—as in the case of Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991) or Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen (1986)—and they continue to grow in popularity.

Questions to Consider:

- What could you learn by looking at books and publications about American art?

- What is the plot of Lynd Ward’s pioneering God’s Man?

- Have you ever “read” a graphic novel? Which one(s)? How would you describe the experience?

Further Reading

Frances Pohl, Framing America: A Social History of American Art (2012)

Erika Doss, American Art of the Twentieth-Twenty-First Centuries (2017)

David Bjelajec, American Art: A Cultural History (2000)

Wayne Craven, American Art: History and Culture (2002)

Sharon F. Patton, African-American Art (1998)

Wendy Greenhouse, “The Collection of Portraits by George Peter Alexander Healy in the Newberry Library,” 1999, Newberry Library, Chicago.