This collection contains contributions by Alexandra Thomas and Suzanne Karr Schmidt.

Introduction

With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people turned to historical plagues to understand the present crisis. In the United States, Google searches for “the Black Death” and “Spanish flu” spiked in March 2020. In the same month, sales of plague fiction (such as Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, and Albert Camus’ The Plague) surged. Notably, with the exception of the Spanish flu and Camus’ novel, all of these points of reference derive from the medieval and early modern periods.

Outbreaks of disease were a part of life in premodern communities. In London, for example, the Black Death of 1347-48 likely killed between 25% and 40% of the wealthiest residents. (Mortality was probably much higher amongst the poor.) In the following centuries, the plague did not simply disappear, but recurred frequently. In the late 1400s and early 1500s alone, London experienced plague outbreaks in 1479, 1498-1501, 1504, 1513, 1518 and 1521, interspersed with bouts of the so-called “sweating sickness” in 1485, 1508, 1517, 1528 and 1551. The early seventeenth century brought little relief: in 1603, one in five Londoners was killed by the plague in the space of three months. While the plague began to subside in London, as in Europe on the whole, in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, other diseases came to the fore; smallpox, for example, caused 10% of all deaths in the city by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

As in the twenty-first century, people, goods, and animals travelled along many vectors in the premodern world, and they brought disease with them. Infected rats on grain ships carried the bubonic plague across the Black Sea and into Italy in the mid-1300s. Two centuries later, the Spanish invasion carried smallpox to the Americas. Yet if disease travelled, so, too, did medical knowledge. Sixteenth-century Europeans believed both syphilis and its alleged cure, guaiacum to have originated in the New World. Smallpox inoculation, which paved the way for modern-day vaccination, was introduced to England in the eighteenth century after aristocrat Mary Wortley Montagu observed the procedure being performed in the Ottoman Empire.

In this collection, we will likewise traverse the globe as we explore a few of the many ways disease shaped life in the medieval and early modern eras. Section 1, “Medicine,” examines how people understood and sought to treat disease at various times and places in the premodern world. Section 2, “Economics, Governance, and Warfare,” considers the relationship of disease to society and politics. Section 3, “Religion,” investigates how people sought solace and deliverance in faith during times of plague. Finally, section 4, “Art and Literature,” reveals how epidemics inspired the production of literary and artistic works and even fostered the growth of new genres. Across these various themes, times, and places, we’ll seek to answer the overarching question: What can we learn from premodern plagues?

Some entries here have been adapted from videos in the “Learning from Premodern Plagues” series.

Guiding Questions:

- How did people understand and treat diseases in the premodern world?

- How did disease shape various facets of premodern life, including religion, economics, governance, and culture?

- How did disease move from one part of the world to another? How does studying disease enrich our knowledge of the various ways that goods and people travelled in the premodern world?

- What can we learn about how and how not to navigate pandemics in our contemporary world by studying premodern plagues?

Medicine

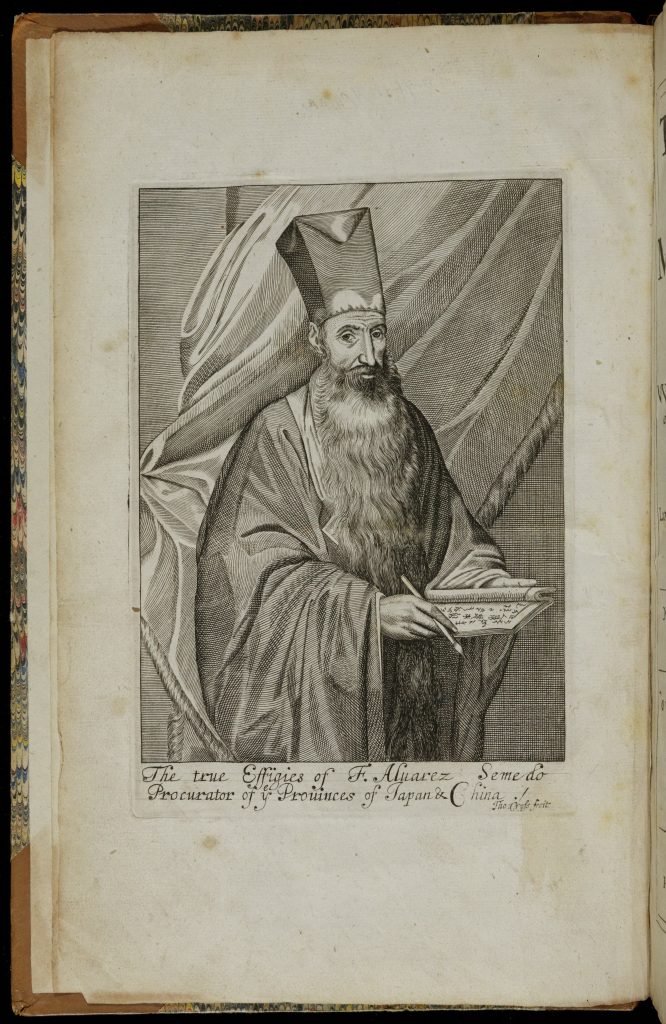

Álvaro Semedo, The History of that Great and Renowned Monarchy of China, Frontispiece, 55-58 (1655).

This excerpt from The History of that Great and Renowned Monarchy of China, a travel account penned by Portuguese Jesuit Álvaro Semedo, yields insights into seventeenth-century Chinese medical practices and Jesuit missionaries’ interest in them. Semedo arrived in Macau, then a Portuguese base, in 1613, and traveled around various parts of China, including Nanjing, Canton, Hangzhou, and Jiangxi, until 1637, when he returned to Europe before embarking on a second trip to China in 1644. During his interval in Europe, Semedo, like many Jesuit missionaries, compiled a detailed account of China and its culture, which was published in the early 1640s and translated into English in 1655.

Semedo focuses on two aspects of Chinese medicine: pulse diagnosis and pharmacology. Pulse palpation was the central diagnostic technique in classical Chinese medicine. Doctors evaluated the patient’s heartbeat on a number of criteria (including, but not limited to, its speed), and sought to thus assess a person’s qi, or psycho-physical essence. Contrary to Semedo’s account, physicians might also examine the patient’s physical condition through other means and ask for information about the symptoms and phases of the illness. The pulse diagnosis informed the doctor’s therapeutic decisions, and Semedo presents herbal medicines as the chief remedy. Chinese physicians employed a wide repertoire of medications, many unknown to Europeans. The production of Chinese pharmacological texts increased substantially during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, at the same time that the publication of “herbals” (books describing plants and their medicinal uses) flourished in Europe. The Jesuits collected these Chinese books and often described medicinal plants in their accounts. Elsewhere in his History, for instance, Semedo discusses camphor and rhubarb, and he appears to have been the first European observer to mention the root ginseng.

Marsilio Ficino, Il consiglio di M. Marsilio Ficino fiorentino contro la pestilentia [Marsilio Ficino of Florence’s Advice Against the Plague], Title page, folio 3r (1556).

Marsilio Ficino was a fifteenth-century humanist, philosopher, and priest. He wrote Il consiglio di M. Marsilio Ficino fiorentino contro la pestilentia (Marsilio Ficino of Florence’s Advice Against the Plague) in the vernacular Tuscan (Italian) so that “every Tuscan person” might use the book to medicate themselves against the plague.

Ficino asserts that the “poisonous vapors” of the disease are “inimical,” or hostile, “to the vital spirit,” and one must diligently defend against them through many different methods. Chapter V discusses how people should change their behavior to protect themselves. They must refrain “from things that inflame [the body] and open much” (that is, open the pores, the humors, etc.) by avoiding “great heat outside, the sun, fire” and warm clothing. They should not eat too much salt; however, “cold, dry, sour, bitter, and/or acidic/vinegary” fruits and herbs (and other foods classified as such) are safe. Chapter VI addresses medical means of combating plague. Ficino offers recipes for various remedies and lists beneficial herbs. He also attributes the plague to astrological causes: “the universal plague [is] caused by a fatal conjunction of the Planets, very terrible and frightening, and long.” Finally, he cautions the reader that “the pestilent poison” spreads most quickly at dawn, dusk, noon, and midnight, and that it “reigns in the spring, more in the summer, more in the autumn.” He attributes these temporal variations to solar and seasonal effects on the air.

Entry by Alexandra Thomas.

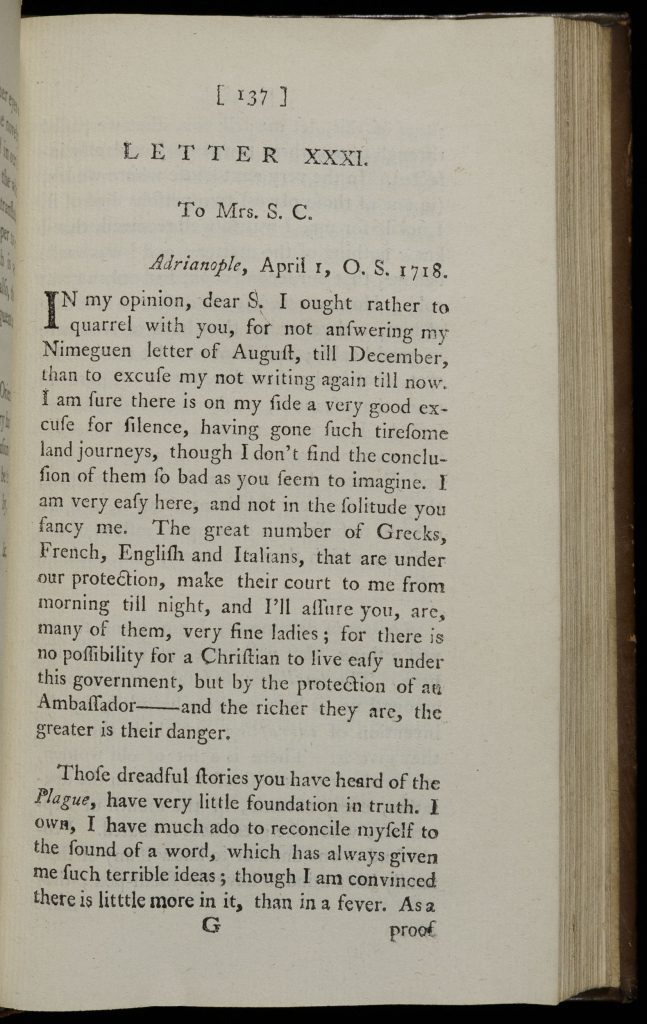

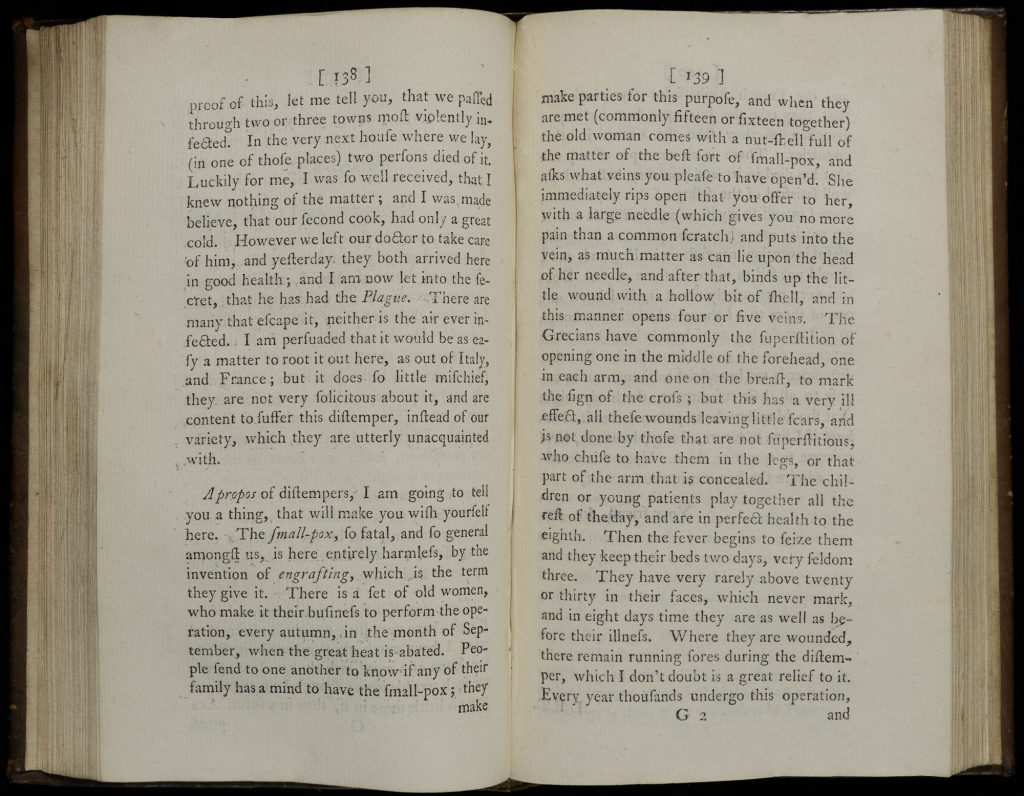

Mary Wortley Montagu, Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M—y W—y M—e, Title page, 137-140 (1763).

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762) was an English aristocrat and prolific letter-writer who promoted the adoption of smallpox inoculation in England. When her husband was appointed as the ambassador to Turkey in 1716, the couple traveled to Constantinople. During the journey, Lady Mary observed the process of “engrafting,” or inoculation. Through this procedure, individuals were exposed to a small amount of infectious matter from a smallpox patient, causing them to develop a mild form of the disease to which they would then be immune after recovering. Convinced of the practice’s safety and effectiveness, Lady Mary had her own children inoculated and advocated for the adoption of the practice in England after she returned home, sparking a virulent debate on the subject. Though inoculation fluctuated in popularity throughout the eighteenth-century, it paved the way for Edward Jenner’s invention of vaccination in 1796. Consequently, whereas smallpox killed an estimated seven percent of all children in seventeenth-century England, the disease has since been eradicated worldwide.

Adapted from a video by Stephanie Reitzig.

Discussion Questions:

- Compare and contrast how early modern Chinese medicine (as described by Semedo) and European medicine (as exemplified by Ficino) conceptualized disease. You might consider questions like: What causes illness? How does disease spread? What can we do to treat or prevent it?

- Both Montagu’s and Semedo’s texts are travel accounts, meaning that their authors describe medical practices witnessed abroad to audiences in their native countries. How does each author seemed to have learned about these medical practices? What details about Chinese/Ottoman medical care do they offer, and how do they depict these aspects of medical practice—as positive/negative/neutral, effective/ineffective, safe/dangerous, strange/familiar, or something else?

- Many people in eighteenth-century England were skeptical of inoculation when it was first introduced, despite the fact that inoculation had long been used to prevent smallpox in the Ottoman Empire. Similarly, some people today have expressed hesitation about the COVID-19 vaccine, even though scientific evidence shows that the vaccine is safe and effective. Explore this website about the COVID-19 vaccine from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compare and contrast how the website seeks to persuade its readers of the safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine with the way that Montagu attempts to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of inoculation to her correspondent. What types of evidence do they draw upon? What kind of language do they use to talk about COVID-19/smallpox and about vaccination/inoculation?

Economics, Governance, and Warfare

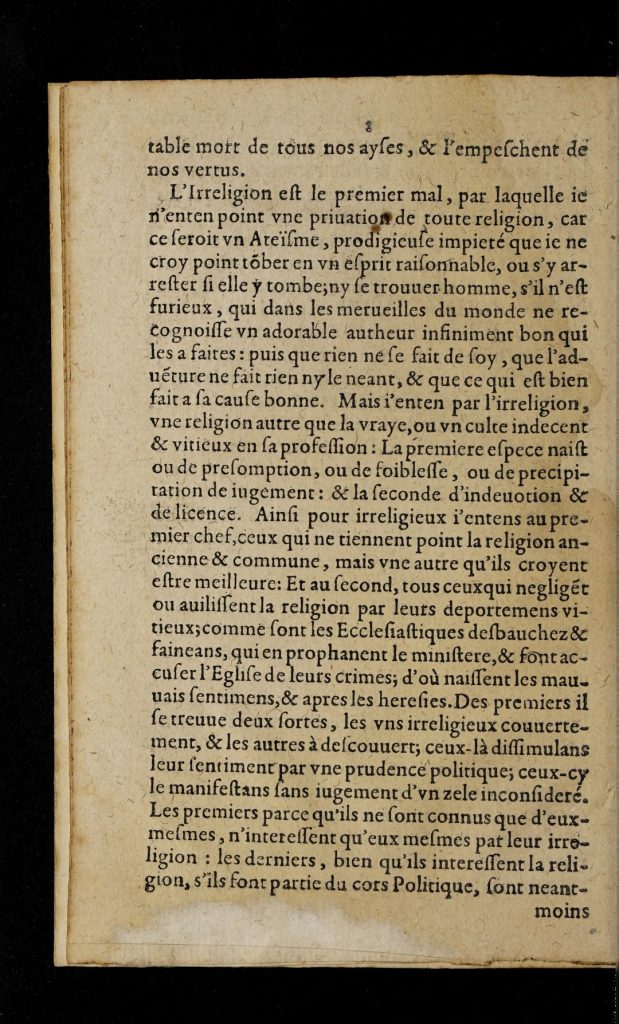

Pierre de Mouilhet, Discours politique au roy [Political Discourse to the King], title page, “Avx Lectevrs,” 3-8 (1618).

This pamphlet, the Discours politique au roy (Political Discourse to the King), was written by Pierre de Mouilhet and published in Paris in 1618. European medicine from antiquity through the early modern period held that the body was composed of four humors and corresponding elements (blood/air; bile/fire; melancholy/earth; and phlegm/water). Mouilhet asserts that a kingdom is similarly composed of these humors, which he associates with the nobility, the church, the people, and justice, respectively. Just as a body is susceptible to disease when its humors are out of balance, he argues, so too is a kingdom weakened when these segments of society are imbalanced. He further attributes the spread of illness to miasma (bad air released from decaying bodies), rejecting the idea that “pestilence” is caused by the movement of the stars. Mouilhet calls for King Louis XIII to institute a variety of measures, financed with public funds, to prevent the transmission of illness, such as ensuring that the dead are promptly and deeply buried, and that graves and other burial places are not opened while the bodies inside are rotting. The continued need in Europe to respond to outbreaks of plague and other diseases from the fourteenth century onward led to the development of what we know today as public health agencies and government oversight over disease prevention and management.

Adapted from a video by Elisa Jones.

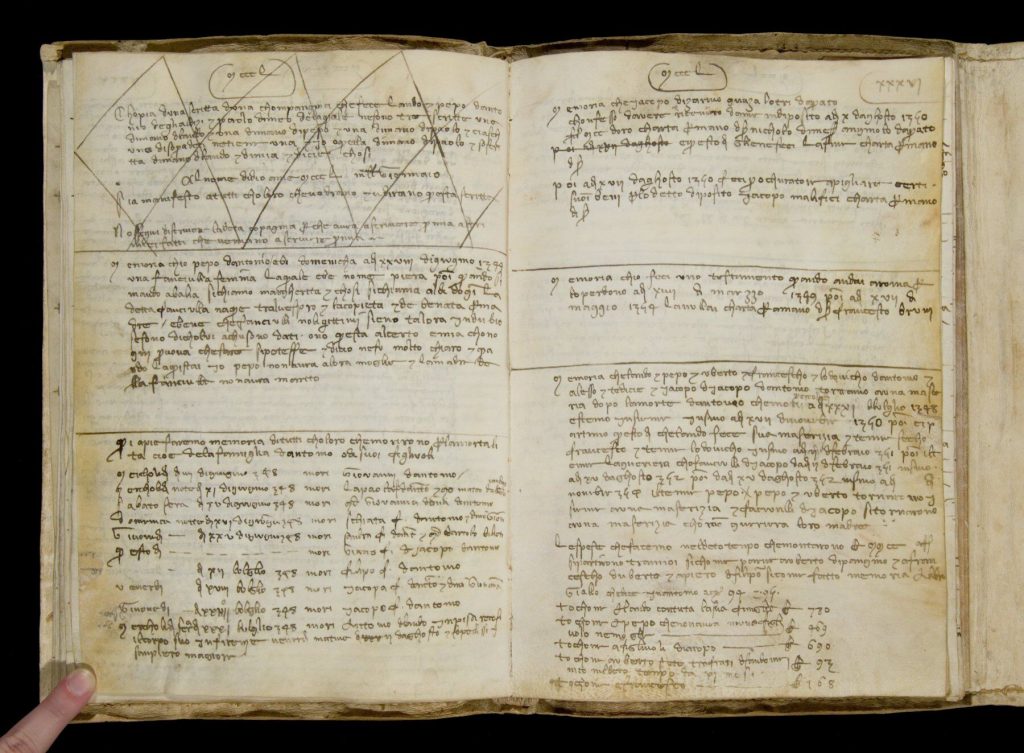

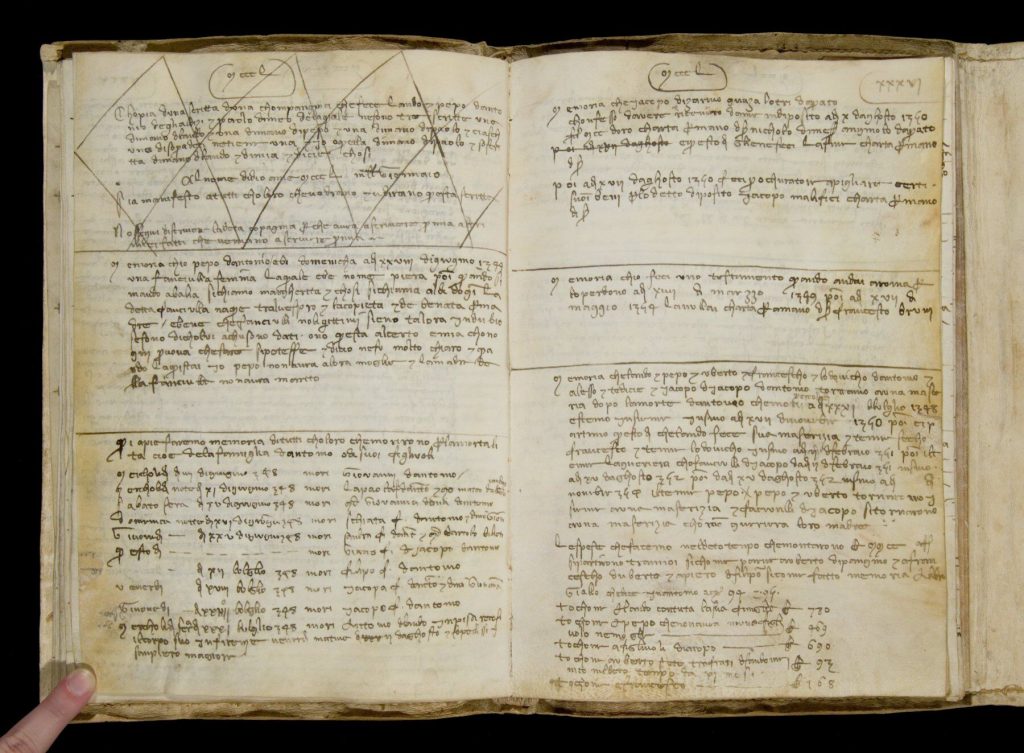

Pepo degli Albizzi, Secret Ledger and Memorial Book, xxxvi (1340-1380).

This memorial book, written by Pepo degli Albizzi in Florence between 1340 and 1380, reveals the many and various impacts of the Black Death on people’s lives. Part ledger, part diary, the book contains records of Pepo’s business affairs and important personal events, as well as Pepo’s memories of the 1348 outbreak of bubonic plague. The origins of the Black Death can be traced back to the early thirteenth century, but it peaked in Europe between 1347 and 1351, killing between 40% and 75% of Europe’s population. In Florence, the pandemic peaked in summer 1348. Pepo recorded a list of family members who died from the disease in his book: between June and July 1348, Pepo lost half of his immediate family, including his father, stepmother, nephew, and seven of his thirteen siblings. The pandemic also had long-lasting effects on Pepo’s family business, as the Albizzi were wealthy and powerful wool merchants in medieval Florence. Prior to the plague, Pepo’s father, Antonio, ran the business, which experienced its highest revenues in 1347. After Antonio’s death, Pepo and his surviving brothers took over the business, which never again reached its pre-pandemic level of success.

Adapted from a video by Isabella Magni.

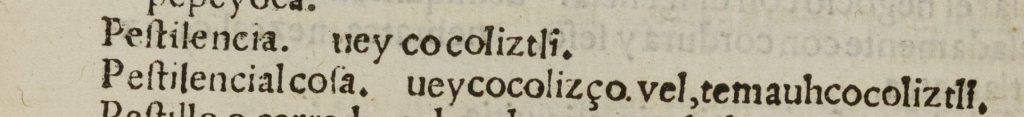

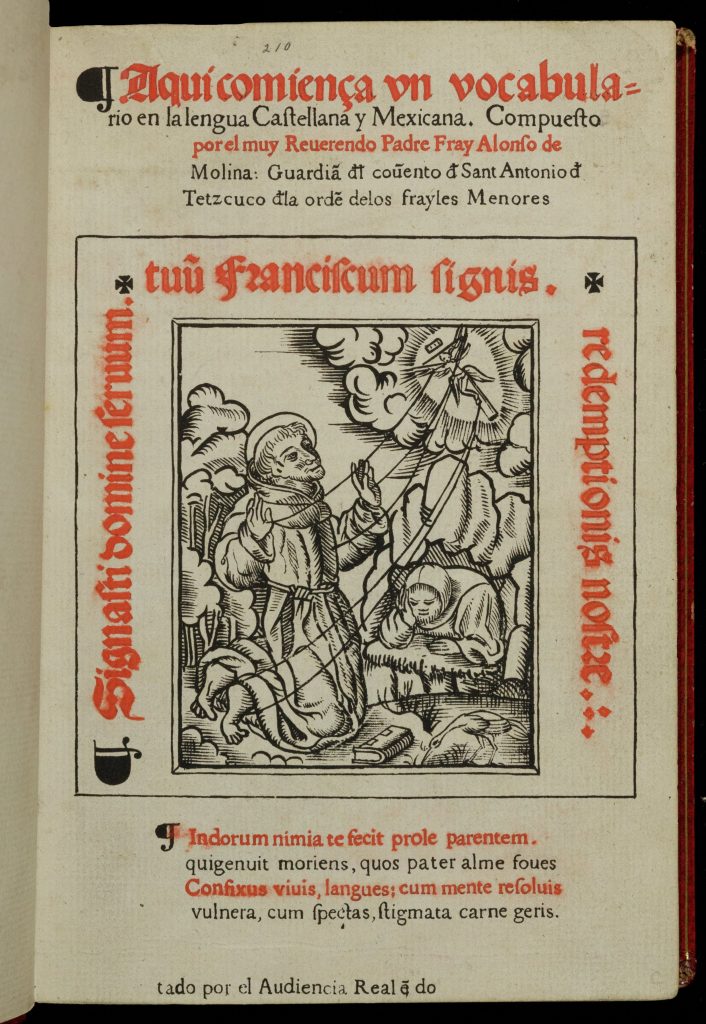

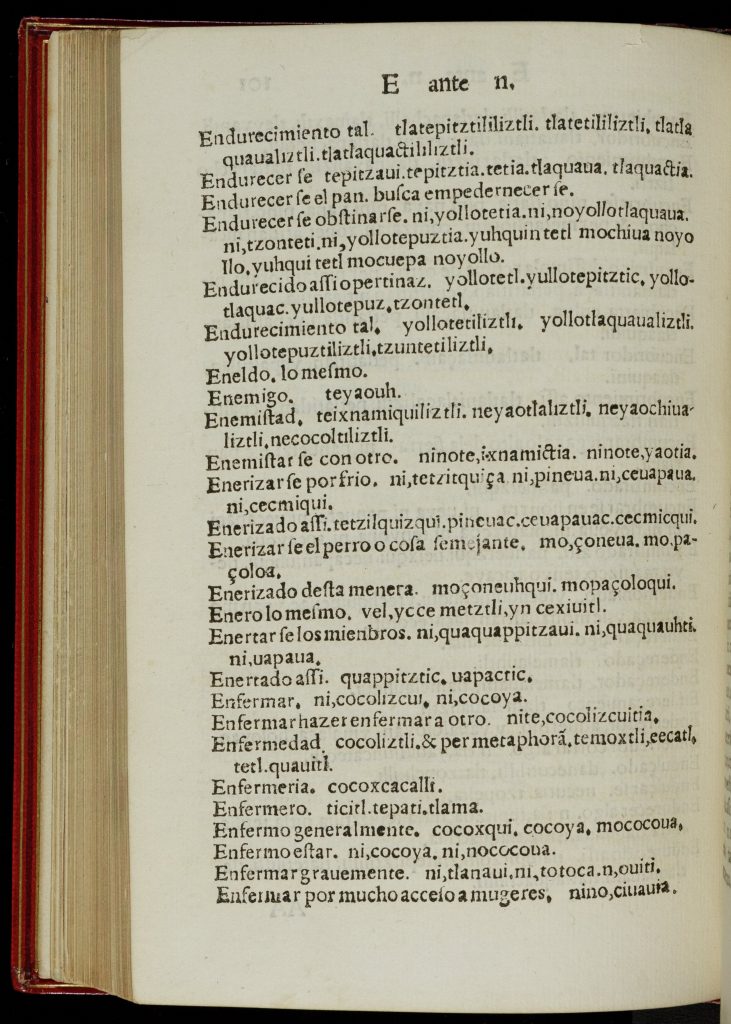

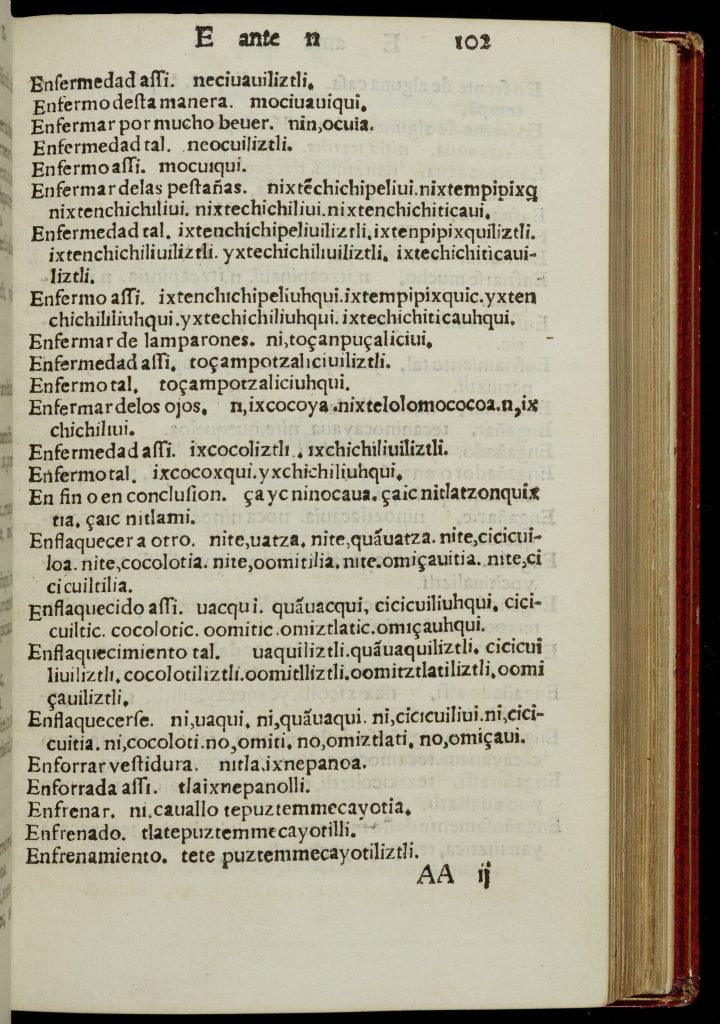

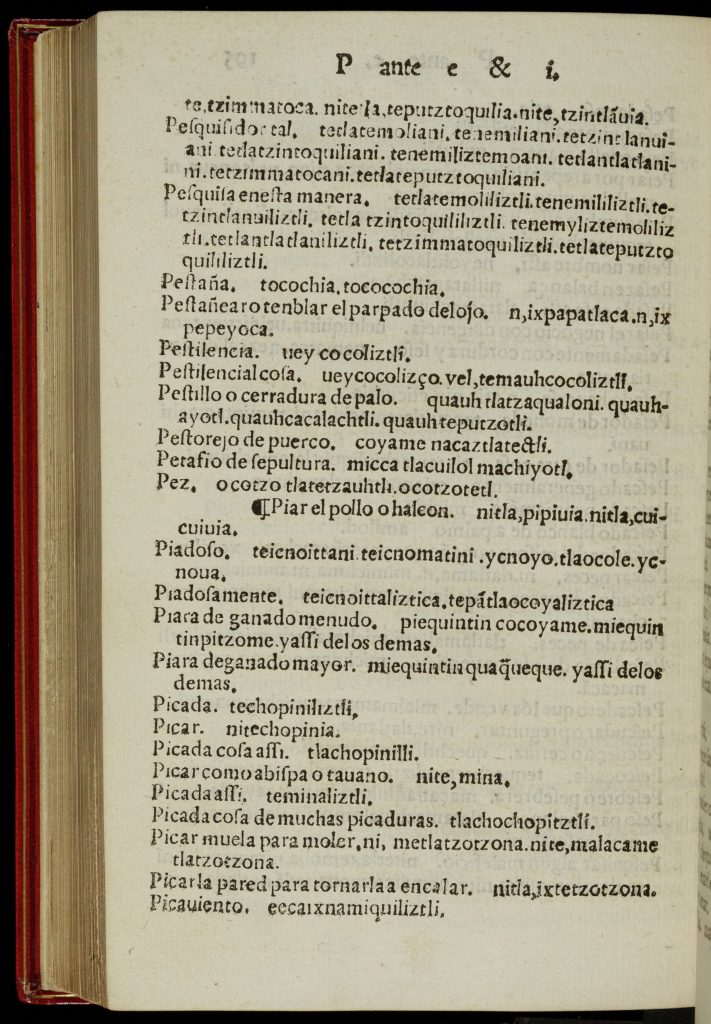

Alonso de Molina, Aqui comiença un vocabulario en la lengua Castellana y Mexicana [Here Begins a Vocabulary in the Spanish and Mexican Languages], Title page, 101v-102r, 195v (1555).

In the sixteenth century, the invading Spanish brought smallpox to the Indigenous societies of the Americas. By the mid-1520s, the disease had spread throughout much of the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America, and had even reached the Inca empire in South America. Smallpox, however, was only one of many epidemics that swept through the Americas in the sixteenth century. In 1576, for instance, the Valley of Mexico was ravaged by an epidemic known by its Nahuatl name huey cocoliztli (“the great pestilence”), possibly what we now understand as hemorrhagic fever. Chroniclers mentioned the epidemic’s unequal effects, relating that Black and Indigenous people died in far greater numbers than the Spanish did. The cumulative impact of these multiple diseases was so great that, by the end of the 1500s, the Indigenous population of the Valley of Mexico may have been only 10% of what it was prior to the Spanish invasion.

The number of entries pertinent to sickness—such as “enfermedad”/“ni,cocolizcui” (illness) and “pestilencia”/“uey cocoliztli” (pestilence)—in Alonso de Molina’s 1555 Spanish-to-Nahuatl dictionary attest to the prevalence of disease in sixteenth-century Mexico. Molina, a Franciscan priest and grammarian, was born in Spain, but arrived in Mexico as a child. He grew up playing with Nahuatl-speaking children in Tenochtitlan and became a fluent speaker of the language. Aqui comiença un vocabulario en la lengua Castellana y Mexicana (Here Begins a Vocabulary in the Spanish and Mexican Languages) was the first dictionary printed in the Americas, and was compiled with the assistance of Hernando de Ribas, a Nahua intellectual from Texcoco. These and other dictionaries and grammar books created by the friars were designed to aid in the conversion of the Indigenous population to Christianity.

Adapted from a video by Claudia Brittenham and a collections presentation by Analú María López.

Discussion Questions:

- How does Mouilhet’s understanding of illness (its causes, how it spreads, and its effect on society) shape his conceptualization of the kingdom of France and how it should be governed?

- Though their texts take different forms, both Molina and Semedo (see Section 1) were missionizing figures who sought to convert people to Christianity. What is/are their purpose(s) in writing? Why do you think they include sections related to health and medicine?

- Imagine that three historians consult Pepo’s ledger. One is studying the impact of the plague on Florence’s economy; another is interested in family life in fourteenth-century Italy; and the last wants to estimate the overall mortality rate from the Black Death in Florence in the summer of 1348. What could each of these scholars learn from Pepo’s diary? What kinds of questions might they have which couldn’t be answered by Pepo’s diary?

Religion

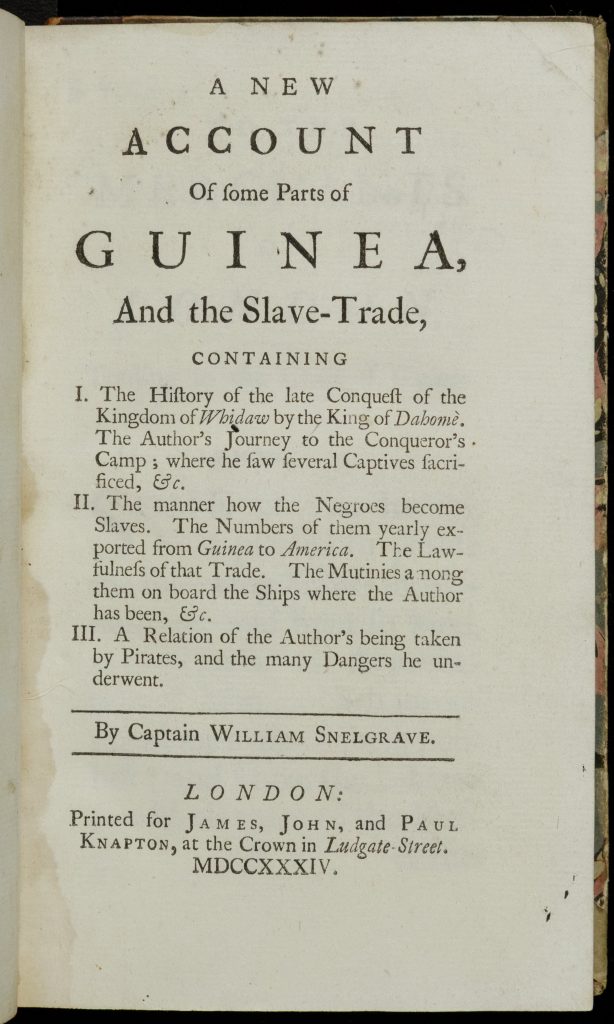

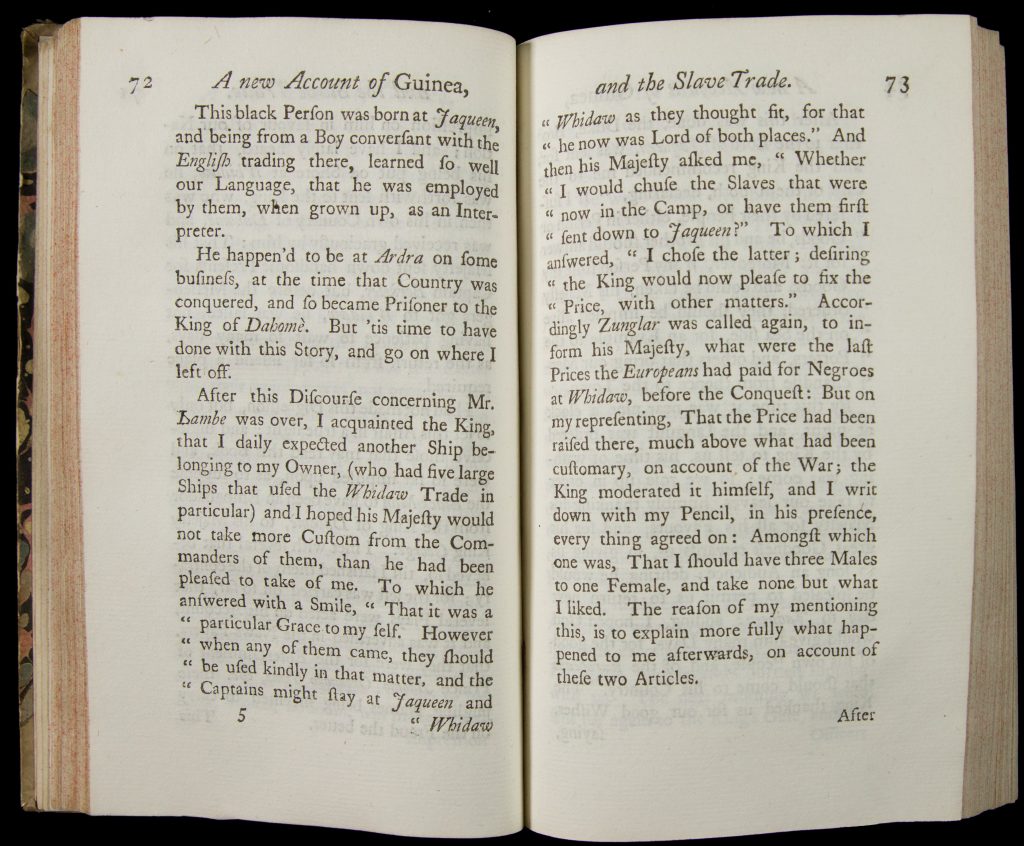

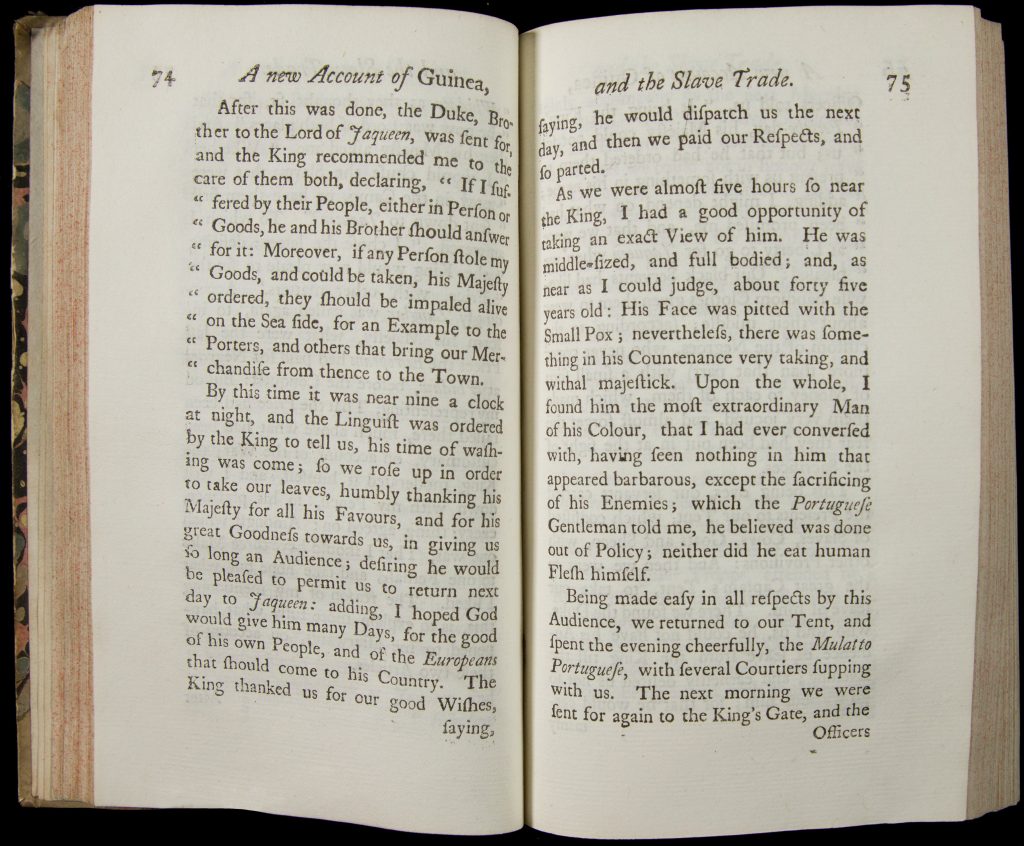

William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, and the Slave-Trade, Title page, 72-75 (1734).

Religious practice, political power, and disease intersected in early eighteenth-century Dahomey, then the most powerful kingdom in West Africa. Dahomean spirituality centered around voduns, or deities, and was mostly localized until the 1720s, when King Agaja began to centralize religious practice. In doing so, Agaja sought to strengthen his authority and weaken the political power of religious cults, particularly that of Sakpata. Originally the vodun of the earth, Sakpata was associated with smallpox by the first quarter of the eighteenth century, when a series of epidemics began to ravage Dahomey. Infected individuals turned to Sakpata priests, seen as the only ones able to intervene with the disease. As their adherents surged, the political and economic power of the Sakpata priests increased dramatically, threatening the monarchy’s authority. Kings also feared the priests’ ability to control the disease itself, and their anxieties appeared confirmed after several rulers died of smallpox. Agaja, unable to kill the priests for fear of inciting their followers to rebellion and angering the vodun, decided instead to sell the Sakpata priests into the Atlantic slave trade. Enslaved people who survived the horrific Middle Passage brought the disease, but also their religious beliefs, to Brazil, where they forged new Afro-Brazilian spiritual traditions.

These developments underpin the experiences described in William Snelgrave’s 1734 A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, and the Slave Trade. By 1734, Snelgrave had been a slave trader for over thirty years, and in this passage he recounts his negotiations with king Agaja, whose face “was pitted with the Small Pox,” and from whom he would purchase some 600 slaves. It is important to note that Snelgrave’s New Account was written with the express purpose of justifying the Atlantic slave trade.

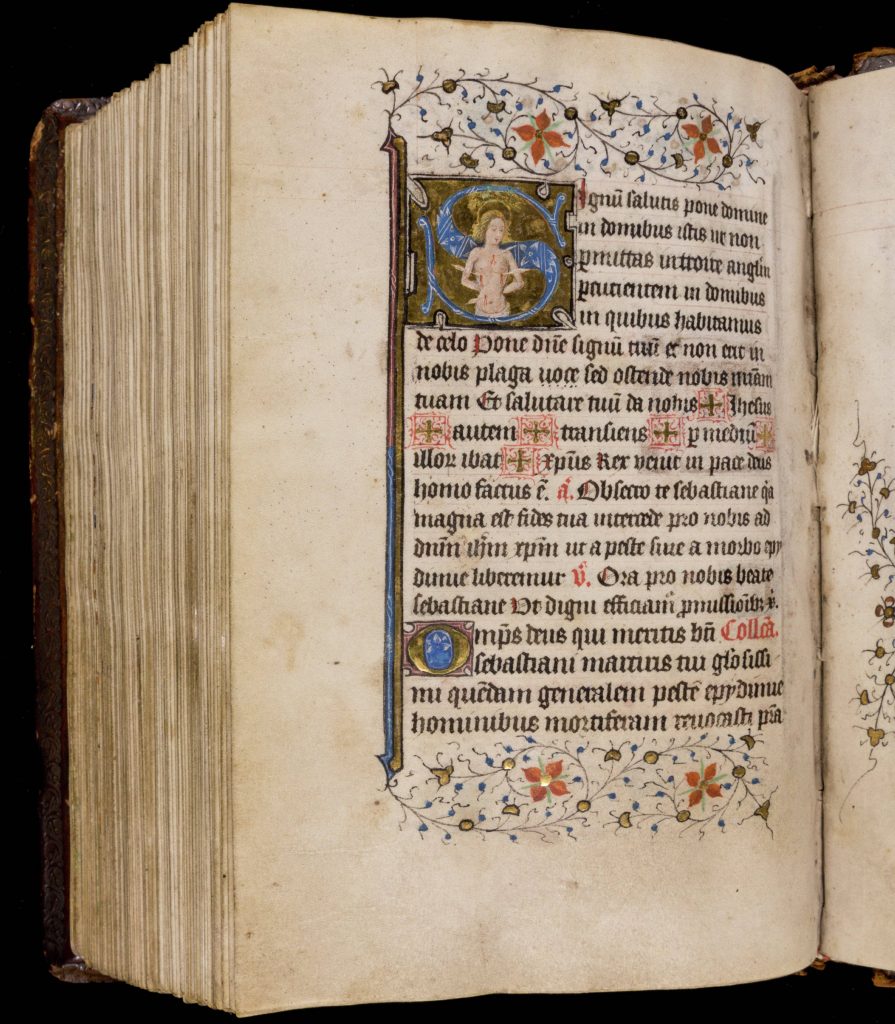

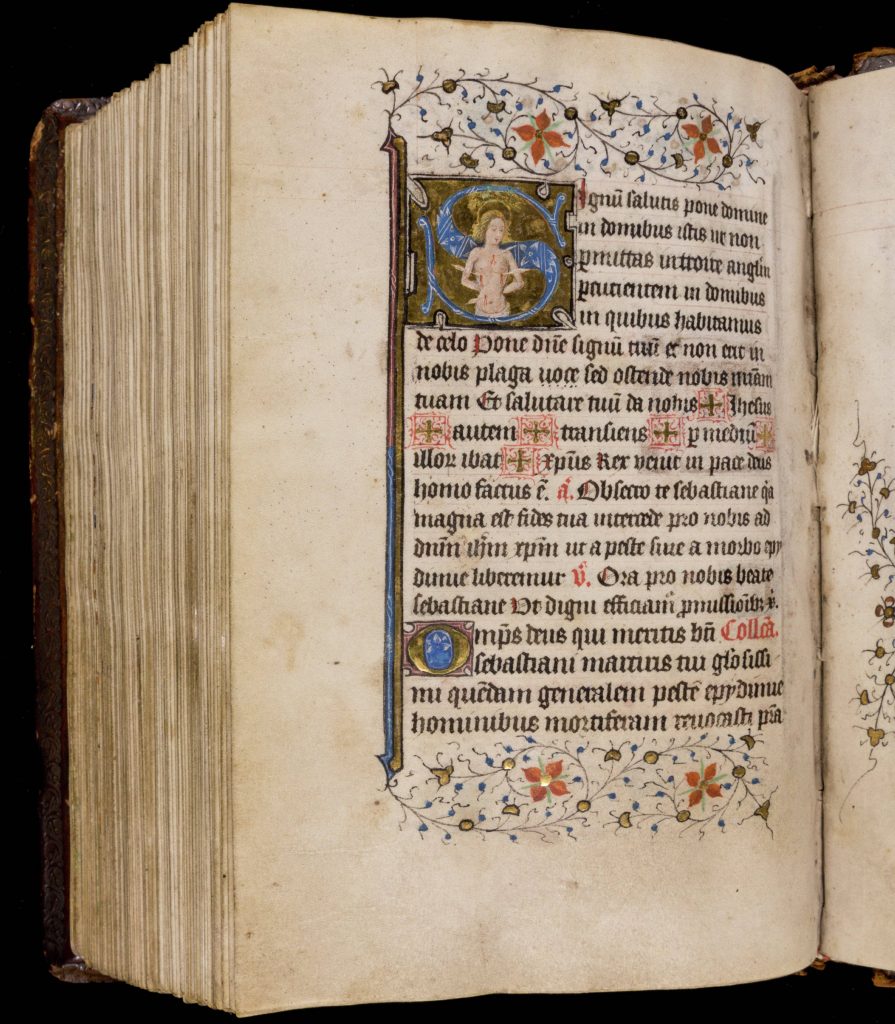

Prayerbook of Margaret of Croy (c. 1450).

St. Sebastian is the patron saint of the plague, and his frequent appearances in late medieval art, music, and religious culture speaks to the influence of the Black Death on devotional life. Supposedly born in Gaul in the third century, Sebastian was a Roman soldier who converted to Christianity and encouraged others to do the same. When Emperor Diocletian ordered that Sebastian be executed by arrows, Sebastian survived. Because arrows were a common metaphor for pestilence, and because the black buboes (enlarged lymph nodes) of the bubonic plague somewhat resembled arrow wounds, Sebastian became a common intercessory saint for individuals facing a plague outbreak. This prayerbook, created c. 1450 for Burgundian noblewoman Margaret of Croy, includes several suffrages of the saints—that is, prayers which asked specific saints to intercede with God on an individual’s behalf. By praying to St. Sebastian during outbreaks of disease, medieval people hoped he might absorb the pestilential arrows and help them bear the epidemic with fortitude. The inclusion of St. Sebastian in Margaret’s prayerbook indicates that he would have had a special resonance for her during this time, which is unsurprising given that the plague frequently recurred after its initial outbreak in the mid-fourteenth century.

Adapted from a video by Sarah Wilson.

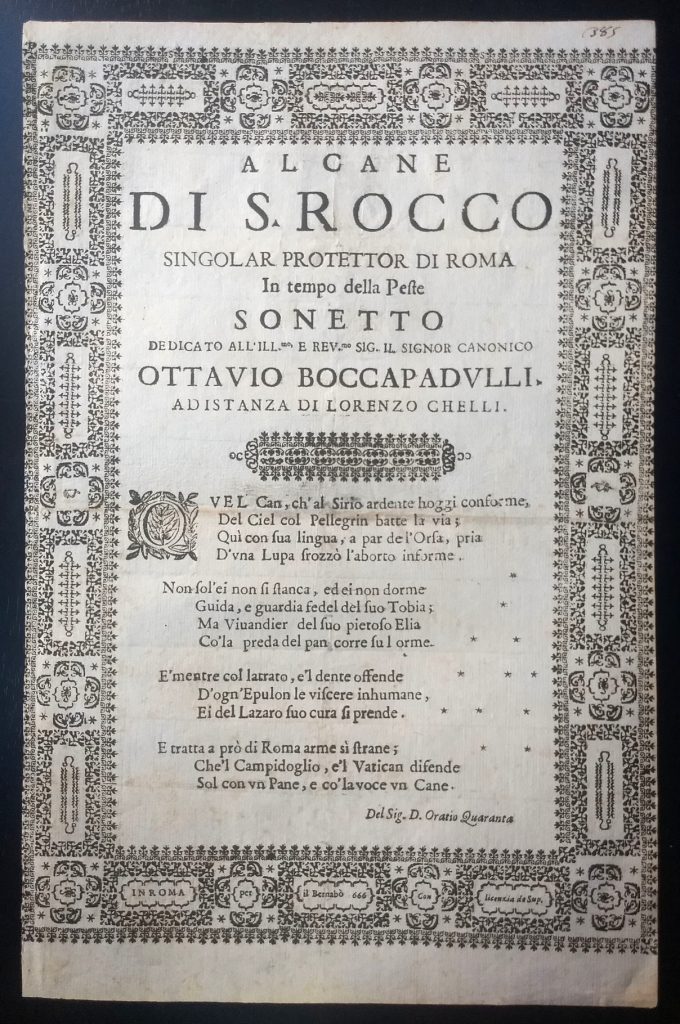

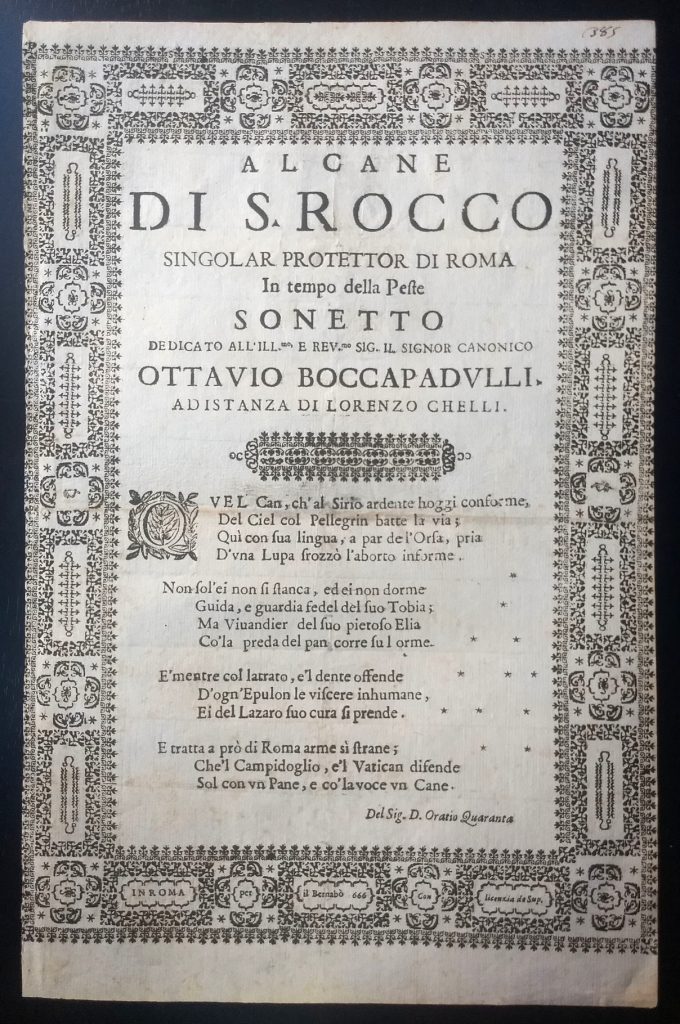

Orazio Quaranta, Al cane di S. Rocco (1666).

St. Roch, who lived c. 1348-1379, is the patron saint of dogs, pilgrims, and plague victims and usually bears the attribute of a sore on his thigh. The sonnet on this 1666 Roman broadside, however, is entitled not in Roch’s honor, but his dog’s. After Roch contracted the plague from tending the sick, a friendly dog nourished him with bread, and healed his wounds by licking them. By saving Roch, the dog in turn saved the other plague victims for whom Roch later cared. For seventeenth-century Romans, thanking the dog for his help in (presumably) warding off the plague when it threatened nearby cities was an indirect way of thanking St. Roch and God. This sonnet expresses civic gratitude that dangerous outbreaks, like those in London in 1665-66, have not afflicted Rome, crediting “his [Roch’s] bread and his voice” for saving the Vatican. The broadside was printed on one side for pasting onto public walls. It is included in an album of ephemeral Italian devotional printings, broadsides which would similarly have been used as posters to announce special feasts and to thank their patron saints.

Entry by Suzanne Karr Schmidt, George Amos Poole III Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts. Orazio Quaranta, To the Dog of Saint Roch (Al cane di S. Rocco). Rome: Stamperia Bernabò, 1666. Acquired with support from the Roger W. Weiss and Howard Mayer Brown Fund.

Companion video by Suzanne Karr Schmidt.

Discussion Questions:

- The case of eighteenth-century Dahomey highlights how disease, religion, and monarchical power could intersect. This is not the first time, however, that we have seen this combination: Mouilhet (see Section 2) begins his Discours with a flowery paragraph describing the favor God has bestowed on Louis XIII. Why do you think he does this, and what does it tell us about how important religion was to Louis XIII? How does this compare or contrast to the way religion affected the power of the Dahomean kings? How might an outbreak of disease affect the relationship of both kings to religion?

- Both the prayerbook of Margaret of Croy and the Roman broadsheets show that premodern Christians turned to the saints in times of plague. However, these objects look very different. How were these two objects made? Which would have taken more time and money to produce? What evidence would you use to back up your thinking? Once finished, were they used and/or displayed in public or in private? How do we know? What does this tell us about the similarities and differences in Christian responses to plague across centuries and class boundaries?

- Today, how has COVID-19 affected faith and devotional life?

Art & Literature

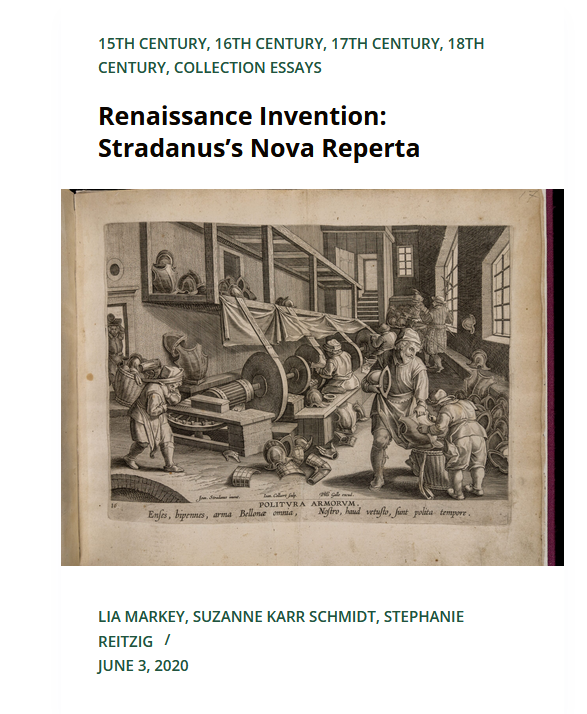

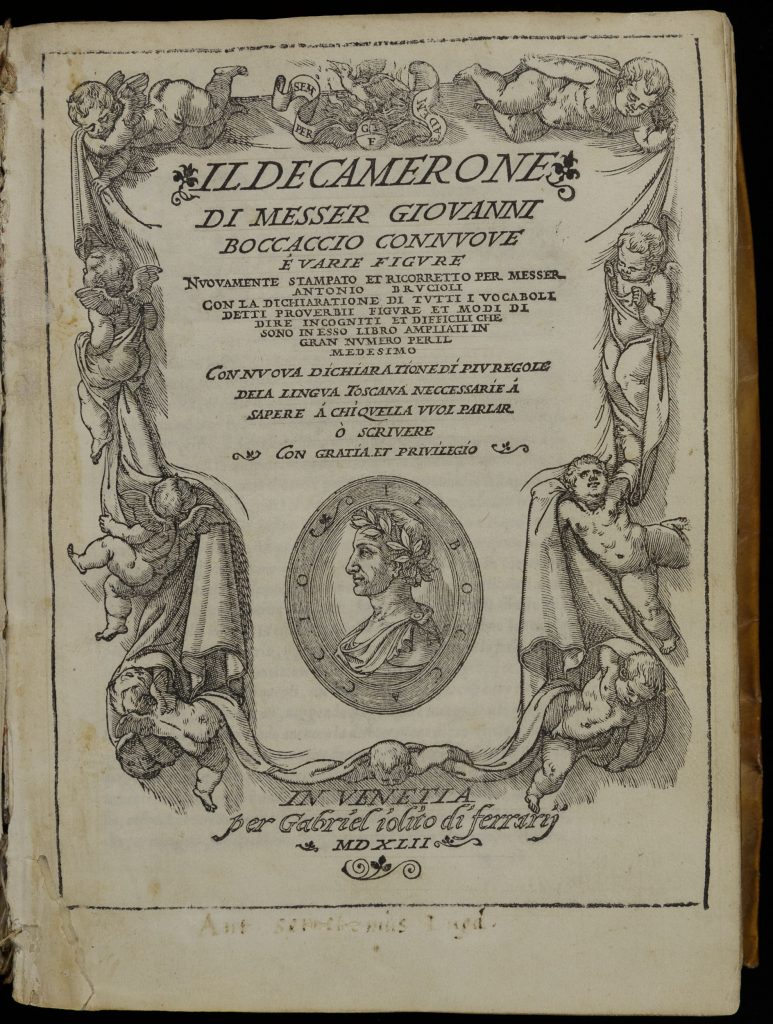

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron, Title page, Chapter 1, Chapter 3, Chapter 7, Chapter 8, (1542).

Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron is a collection of one hundred tales, likely written sometime between 1349 and 1351/52. The Black Death of 1348 functions as a frame narrative for these stories. Boccaccio describes how a group of ten young noble men and women escape the plague-ridden city of Florence by fleeing to the countryside, where they entertain themselves by telling tales. Every day for ten days, a new member of the group is appointed king or queen and dictates a guiding theme for the ten stories to be shared that day. Each chapter of this 1542 edition opens with an illustration depicting one of the day’s stories. The book also contains a decorative frontispiece with a stylized portrait of Boccaccio. Boccaccio himself may not actually have been in Florence when the plague broke out, and his opening account of the plague draws many of its elements from Paulus Diaconus’ eighth-century History of the Lombards. However, his father was the Florentine minister of supply and was tasked with organizing relief during the pandemic, so Boccaccio may have obtained some details of the disaster from him.

An English translation can be found in HathiTrust.

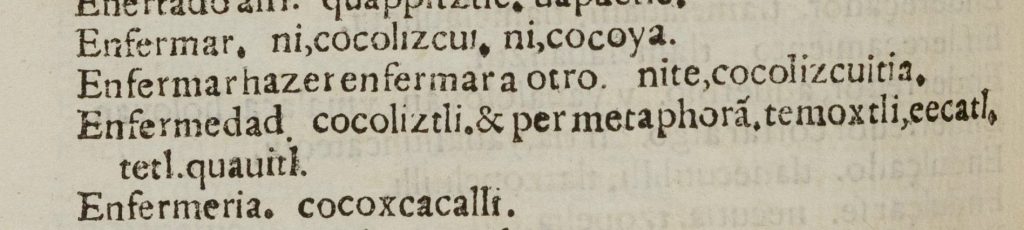

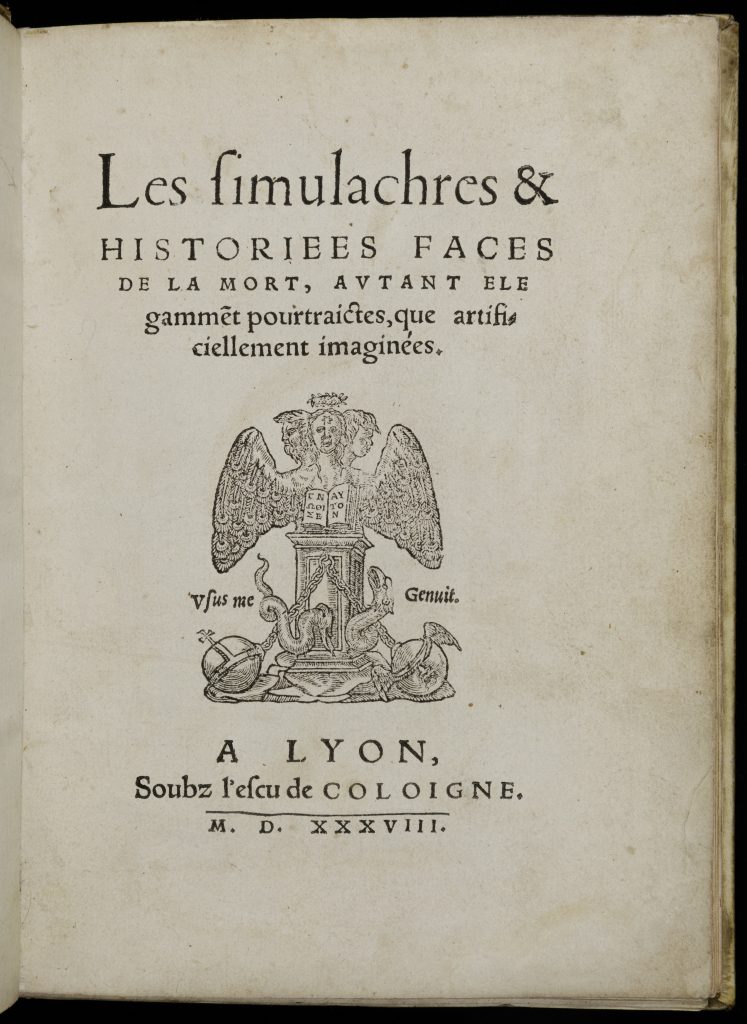

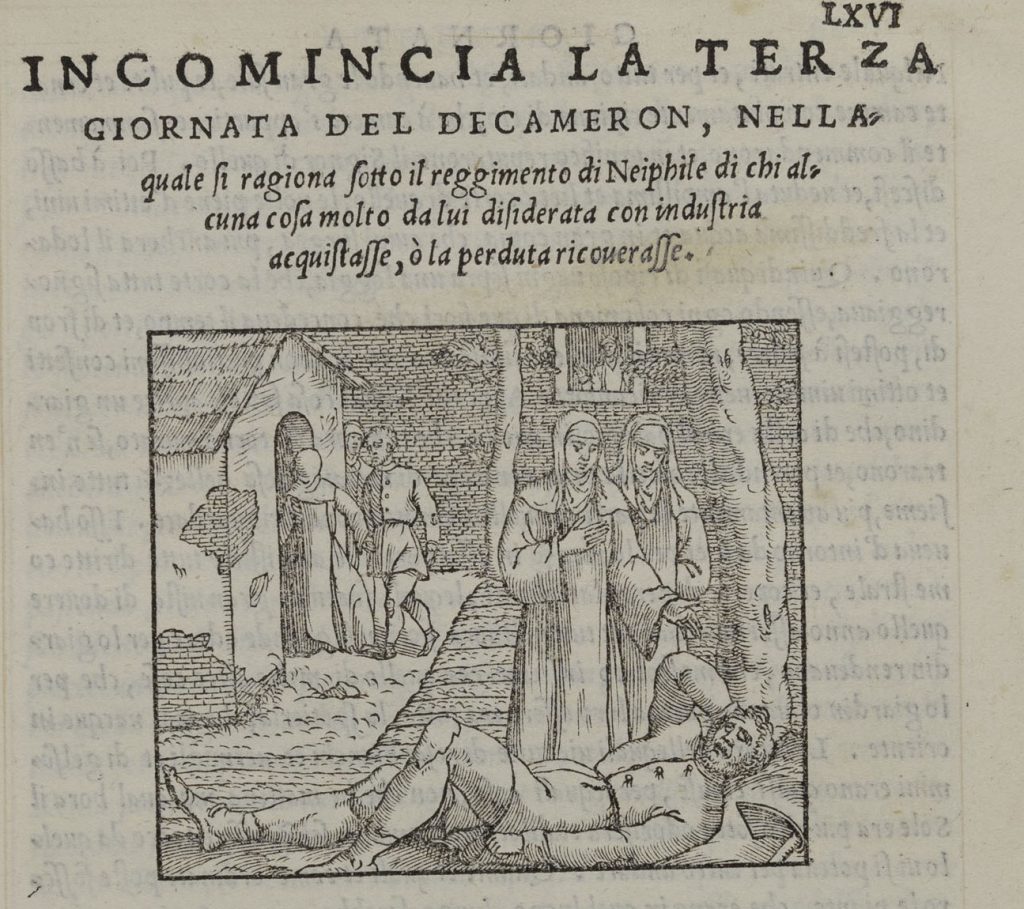

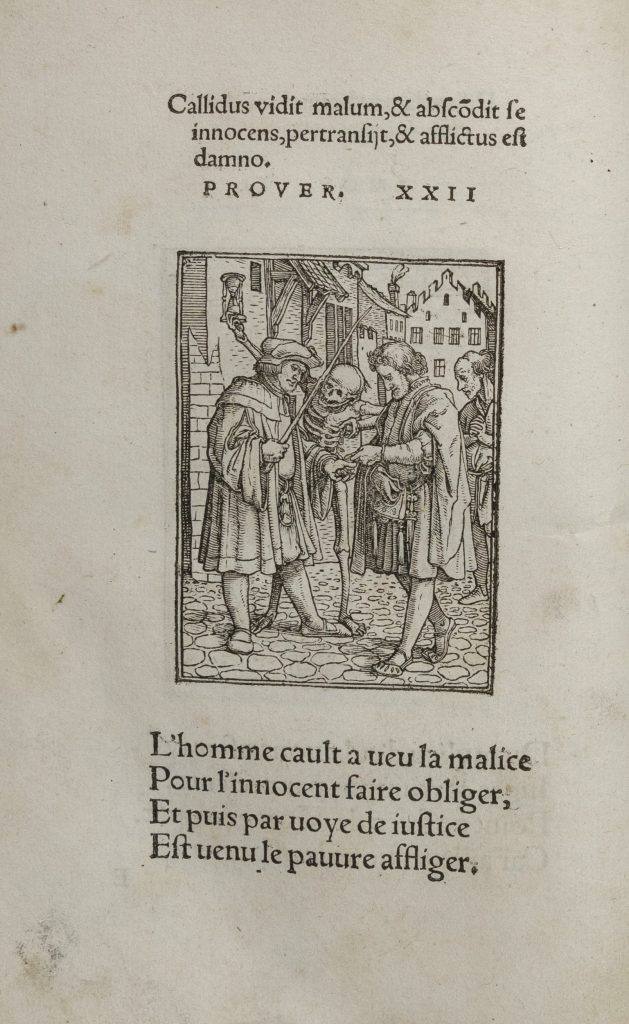

Hans Holbein, Simulachres & historiees faces de la morts [Simulacra and Illustrated Faces of Death], Title page, proverbs 21-22 (1538).

The images of the Simulachres & historiees faces de la morts (Simulacra and Illustrated Faces of Death, better known as the “Dance of Death”) yield insight into mortality, religion, and society in early modern Europe. Holbein’s woodcuts, designed c. 1524-26 and first printed in 1538, draw upon the so-called “dance of death,” a medieval and early modern literary and visual genre which emphasized the inevitability and universality of death. Dance of death texts and images, whether separate or combined, appeared in manuscripts, in print, and in large-scale wall paintings, the latter often in cloisters or cemeteries. For instance, Holbein’s version was likely influenced by one such scene on the cemetery wall of the Predigerkirche in Basel, which may have been painted after the plague of 1439. As with traditional dance of death imagery, Holbein’s portraits depict Death as a gleeful skeleton who menaces individuals regardless of their ages and social standings. This depiction of death as the great equalizer has led some to suggest that the genre arose out of the Black Death, which challenged social hierarchies and threatened social disorder. Other scholars contend, however, that there is no proof for a firm link between the plague and the dance of death.

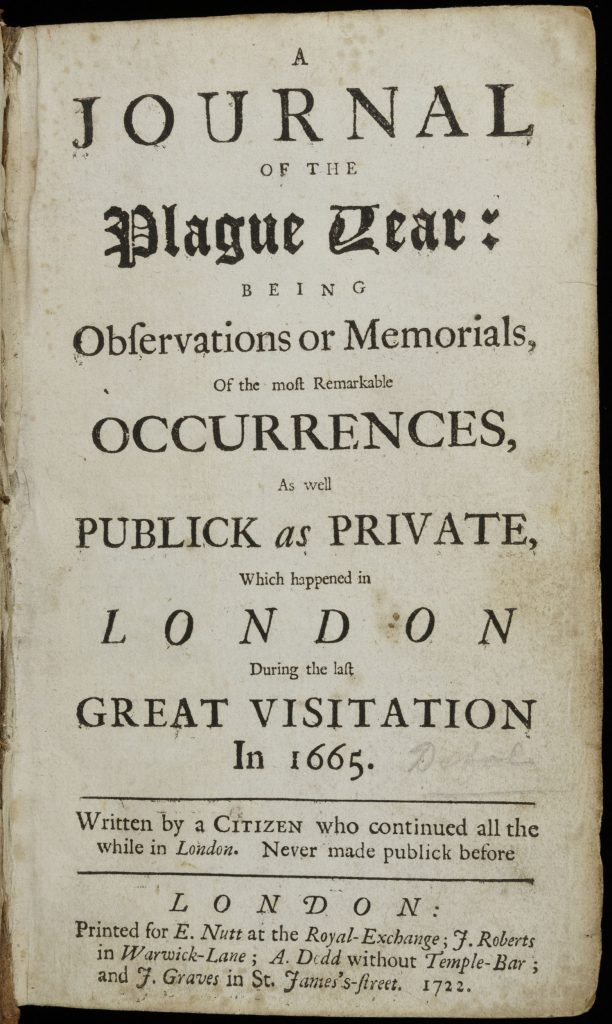

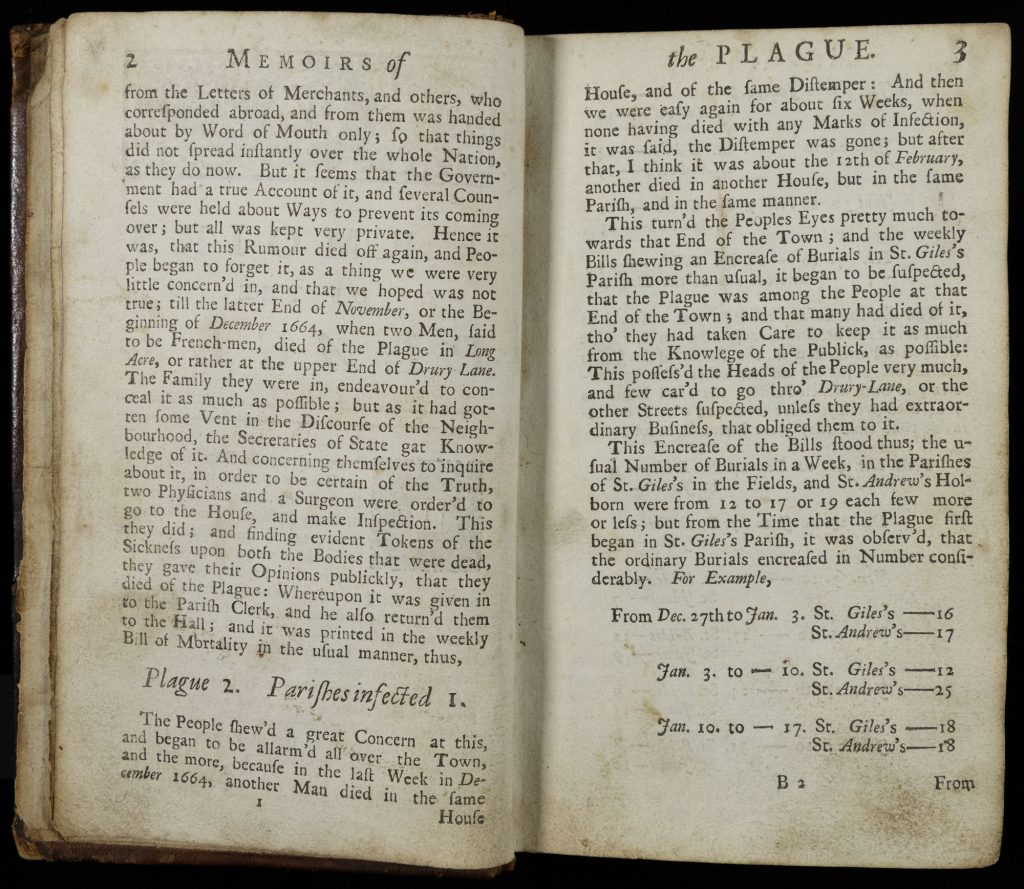

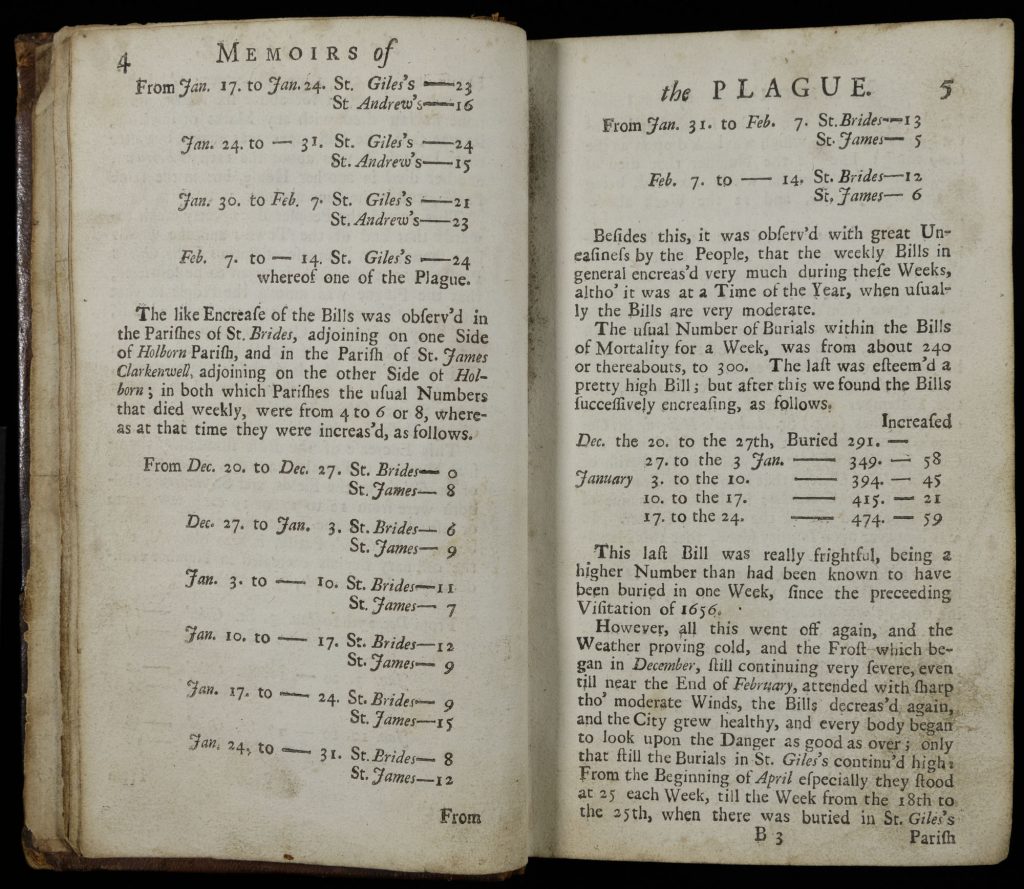

Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year, Title page, 2-5 (1722).

Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel A Journal of the Plague Year presents a fictionalized account of the 1665 plague outbreak in London, which killed an estimated 100,000 people, or approximately 15% of London’s population at the time. During the outbreak, Londoners received news of the plague through printed broadsides known as bills of mortality, which were published weekly and provided data about the number, type, and location of deaths in London in the past week. These bills of mortality functioned as a sort of early newspaper and instilled in people the (new) idea of news as something that was printed and published in regular periodic intervals. Publishers capitalized upon this feeling in the post-plague era by transforming news into a narrative of daily life, while writers began to experiment with new and longer narrative forms like the novel. Defoe includes bills of mortality within the text of his book, and the narrator thus reads an older form of news about the plague while simultaneously offering a more contemporary journalistic account of 1665 London for readers of the 1720s.

Adapted from a video by Jill Gage.

Discussion Questios:

- Look at the people in Holbein’s images. Do their ages, occupations, and clothing appear to be the same or different? Are they aware of Death’s presence, and if so, how do they react to it? How is Death itself portrayed? What does this tell us about how early modern people approached mortality?

- Given that Boccaccio sets the Decameron during the Black Death, it may seem surprising that the book’s stories (some of which Boccaccio wrote before 1348) are known for their bawdy humor. Why do you think Boccaccio chose this catastrophic setting for his comedic tales?

- How are the bills of mortality reproduced in Defoe’s Journal similar to and different from the way people receive information about the COVID-19 pandemic today? Consider blog posts, social media, and other ways that people share their personal experiences in the present day.

- How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the way people create and interact with works of art and literature (e.g. books, movies, artworks)? Do you think the COVID-19 pandemic will have a lasting influence on art and literature? Why or why not?

About the Author

Stephanie Reitzig is a student at the University of Chicago. She was an intern for the Newberry Library’s Center for Renaissance Studies from January 2020 to June 2021.

Further Reading

General

Alden, Dauril, and Joseph C. Miller. “Out of Africa: The Slave Trade and the Transmission of Smallpox to Brazil, 1560-1831.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18, no. 2 (Autumn 1987): 195-224.

Carmichael, Anne G. “Diseases of the Renaissance and Early Modern Europe.” In The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Barker, Hannah. “Laying the Corpses to Rest: Grain, Embargoes, and Yersinia pestis in the Black Sea, 1346-48.” Speculum 96, no. 1 (January 2021): 97-126.

Green, Monica. Introduction to Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World: Rethinking the Black Death, edited by Monica Green, executive editor Carol Symes. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2015.

Harding, Vanessa. “Families in Later Medieval London: Sex, Marriage and Mortality.” In Medieval Londoners: Essays to Mark the Eightieth Birthday of Caroline M. Barron, edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer, 11-36. London: University of London Press, 2019.

Jackson, Mark. The Routledge History of Disease. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

Kiple, Kenneth F., ed. The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Megson, Barbara E. “Mortality among London Citizens in the Black Death.” Medieval Prosopography 19 (1998): 125-33.

Munro, Ian. “The City and Its Double: Plague Time in Early Modern London.” English Literary Renaissance 30, no. 2 (2000): 241-61.

Sanderson, David. “Sales of plague novels soar amid coronavirus lockdown.” April 23, 2020. The Times.

Medicine

Álvaro Semedo, The History of that Great and Renowned Monarchy of China (1655)

Barnes, Linda L. Needles, Herbs, Gods, and Ghosts: China, Healing, and the West to 1848. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Bian, He. Know Your Remedies: Pharmacy and Culture in Early Modern China. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Brockey, Liam Matthew. Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Buck, Charles. Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine: Roots of Modern Practice. London: Singing Dragon, 2015.

Hsia, Florence C. Sojourners in a Strange Land: Jesuits and Their Scientific Missions in Late Imperial China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Gerritsen, Anne, and Stephen McDowall. “Material Culture and the Other: European Encounters with Chinese Porcelain, c. 1650-1800.” Journal of World History 23, no. 1 (March 2012): 87-113.

Smith, Hilary A. “Understanding the ‘Jiaoqi’ Experience: The Medical Approach to Illness in Seventh-Century China.” Asia Minor 21, no. 1 (2008): 273-92.

Unschuld, Paul U. “History of Chinese Medicine.” In The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Mary Wortley Montagu, Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M—y W—y M—e (1763)

Grundy, Isobel. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Comet of the Enlightenment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Grundy, Isobel. “Medical Advance and Female Fame.” Lumen 13 (1994): 13-42.

Jenner, Edward. An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae vaccinae…. London: Sampson Low, 1796. Accessible on HathiTrust.org.

Montagu, Mary Wortley. Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M—y W—y M—e…. London: T. Cadell, 1784. Accessible on Archive.org.

Montagu, Mary Wortley. Selected Letters. Ed. Isobel Grundy. London: Penguin Books, 1997.

Williamson, Stanley. The Vaccination Controversy: The Rise, Reign and Fall of Compulsory Vaccination for Smallpox. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007.

Economics, Governance, and Warfare

Alonso de Molina, Aqui comiença un vocabulario en la lengua Castellana y Mexicana [Here Begins a Vocabulary in the Spanish and Mexican Languages] (1555).

Alden, Dauril, and Joseph C. Miller. “Out of Africa: The Slave Trade and the Transmission of Smallpox to Brazil, 1560-1831.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18, no. 2 (Autumn 1987): 195-224.

Brooks, Francis J. “Revising the Conquest of Mexico: Smallpox, Sources, and Populations.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 24, no. 1 (1993): 1-29.

Fenner, Frank. “Smallpox: Emergence, Global Spread, and Eradication.” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 15, no. 3 (1993): 397-420.

Hessler, John. “Nahuatl as it was: an exploration of the great dictionary of Alonso de Molina.” April 26, 2021. Worlds Revealed: Geography & Maps at the Library of Congress. Library of Congress.

Ramenofsky, Ann. “Diseases of the Americas, 1492-1700.” In The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Tavárez, David. “Nahua Intellectuals, Franciscan Scholars, and the ‘Devotio Moderna’ in Colonial Mexico.” The Americas 70, no. 2 (2013): 203-35.

Religion

William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, and the Slave-Trade (1734).

Boulukos, George E. “Olaudah Equiano and the Eighteenth-Century Debate on Africa.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 40, no. 2 (2007): 241-55.

Alden, Dauril, and Joseph C. Miller. “Out of Africa: The Slave Trade and the Transmission of Smallpox to Brazil, 1560-1831.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18, no. 2 (Autumn 1987): 195-224.

Law, Robin. “Ideologies of Royal Power: The Dissolution and Reconstruction of Political Authority on the ‘Slave Coast,’ 1680-1750.” Africa 57, no. 3 (1987): 321-44.

Law, Robin. “The Original Manuscript Version of William Snelgrave’s ‘New Account of Some Parts of Guinea.’” History in Africa 17 (1990): 367-72.

Kadya Tall, Emmanuelle. “On Representation and Power: Portrait of a Vodun Leader in Present-Day Benin.” Africa 84, no. 2 (May 2014): 246-68.

Parés, Luis Nicolau. The Formation of Candomblé: Vodun History and Ritual in Brazil. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Sweet, James. Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Art & Literature

Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron (1542).

Rebhorn, Wayne A. Introduction to The Decameron, by Giovanni Boccaccio, xxiii-lxvi. Translated by Wayne A. Rebhorn. New York: Norton, 2013.

Hans Holbein, Simulachres & historiees faces de la morts (1538).

Bätschmann, Oskar, and Pascal Griener. Hans Holbein. Translated by Cecilia Hurley and Pascal Griener. London: Reaktion Books, 1997.

Buck, Stephanie. Hans Holbein, 1497/98-1543. Translated by Paul Aston, edited by Chris Murray. Cologne: Küonemann, 1999.

Campbell, Gordon. “Dance of Death.” Grove Art Online. November 9, 2009.

“Death in Medieval Art.” In The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture. Edited by Colum P. Hourihane. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Nuechterlein, Jeanne. Hans Holbein: The Artist in a Changing World. London: Reaktion Books, 2020.

Oosterwijk, Sophie, and Stefanie Knöll. Introduction to Mixed Metaphors: The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011.

Schwab, Winifred. “Letters without Words? The Danse Macabre Initials by Holbein.” In Mixed Metaphors: The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knöll. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011.

Warda, Susanne. “Dance, Music, and Inversion: the Reversal of the Natural Order.” In Mixed Metaphors: The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knöll. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011.