Themes

American Imperialism

Empire

Spanish Colonialism

Periods & Events

Philippine-American War

Philippine Revolution

Spanish-American War

Skills & Documents

Close Reading

Historical Memory

Images

Compelling Question:

Why did the US colonize the Philippines?

Lesson Questions (Supporting Questions):

- What did the United States seek to gain with its presence in the Philippines?

- What made Filipinos fight for their independence?

Lesson Objectives:

- Students will be able to evaluate the causes and impacts of war from American and Filipino perspectives by analyzing primary source materials.

Materials – Documents available for in the Downloads tab

- Access to a computer and projector

- Sources:

- John T. McCutcheon, sketch of a ship towing two boats (high-resolution version) and sketch of Isla de Mindanao (high-resolution version)

- Samuel Shera, photograph of a group of boys (high-resolution version) and photograph of Filipino Boy Scouts (high-resolution version)

- Felipe Agoncillo, “To the American People” (high-resolution version)

- McKinley vs. Hoar,” New York Evening Post (high-resolution version)

- Student vocabulary & source analysis handout

- Supplementary Sources:

- Map of the Philippines (option from the Newberry)

- The Forbidden Book by Abe Ignacio, Enrique de la Cruz, Jorge Emmanuel, and Helen Toribio

- Vestiges of War edited by Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis H. Francia

- The Philippine Revolution by the Library of Congress

- Unknown Soldiers Podcast by James Houser

Process

More background information on the Philippine-American War is provided in the Background section below. Handouts with close reading questions and activity workspace are provided in the Downloads tab.

- Warm-Up Activity: (5 minutes)

- Give students this prompt: What does war look like to you? Draw a sketch depicting any part of it.

- Process Writing Discussion: (5 minutes)

- Ask 2-3 students to share their sketches with the class. Students can also describe their thought processes.

- Assessing Prior Knowledge in Pairs (10 minutes)

- Display the following key terms for students and have them discuss their understandings of the meanings: allyship, civilize, empire, infantilize, infantilization, occupation, othering, sovereignty. Students can brainstorm or take notes in the vocabulary handout. Definitions are provided in the Downloads tab.

- Students can look up unfamiliar terms if needed. Useful resources are the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium Guide and the California Department of Education Model Curriculum Guide.

- Have a class discussion about these terms and solicit student responses about definitions for each. Formal definitions should be copied by students and/or made available on display for accessibility. (5 minutes)

- Sources Sets and Close Reading Activities:

- Documents 1 & 2: Create Captions (10 minutes)

- Document 3: Write a letter (10 minutes)

- Please note: The caption on the back of this photo includes a racist term for Black children, an example of how anti-Black racism in the US was part of American imperialism abroad. The image can be taught without showing students the term.

- Document 4: Discuss in Pairs (10 minutes)

- Document 5: Strong Lines (10 minutes)

- Document 6: Debate Questions (10 minutes)

- Documents 7 & 8: The Cost of War (15 minutes)

- Final Reflection/Discussion (10-15 minutes)

Documents 1 & 2: Create Captions

John T. McCutcheon, sketch of a ship towing two boats and sketch of Isla de Mindanao (1898)

Document Context

Cartoonist John T. McCutcheon worked for several Midwestern and Chicago-based publications such as the Chicago Tribune. He traveled abroad extensively, and he witnessed the Battle of Manila Bay, which was initiated by the United States via Commodore George Dewey’s Asiatic Squadron and General Wesley Merritt’s Eighth Army Corps.

Create Captions: Close Reading Questions

- What do you see in the sketches by John T. McCutcheon? Describe as many details as possible.

- Write an informative, one-sentence caption for each of these sketches.

Document 3: Write a Letter

Samuel Shera, photograph of a group of boys (undated)

Please note: The caption on the back of this photo includes a racist term for Black children, an example of how anti-Black racism in the US was part of American imperialism abroad. The image can be taught without showing students the term.

Document Context

Many white Americans went to the Philippines to serve in the US military. Some stayed after their service and became reporters, photographers, journalists, and collectors. These photos were taken by Samuel Shera, who enlisted in the US Army on December 13, 1898. He served for approximately four years with the US Infantry in the Philippines, perhaps working as a military photographer. Shera remained in the Philippines after being discharged from the Army in late 1901, and he left the Philippines around 1915.

Many photographers like Shera documented Philippine daily life. In this photo and the caption behind it, you’ll see it says, “A group of Pickaninnies,” which is a racist term for young Black children. Filipinos were often called racial slurs for Indigenous and Black peoples, as they were often likewise viewed as an inferior race by white Americans. This racialization of Filipinos as Black reveals an anti-Blackness, along with a lack of cultural understanding of Filipinos as humans with their own names, cultures, and identities.

Write a Letter: Close Reading Questions

- What are your initial reactions to this photo?

- Why do you think Shera captioned his photo this way? Use one of the vocabulary words in your responses.

- Write a letter to one or all of the boys in the photo. What do you wish to know about them?

Document 4: Discuss in Pairs

Samuel Shera, photograph of Filipino Boy Scouts (undated)

Document Contex

Filipinos resisted American occupation in many ways, including joining American-based organizations and taking what they learned to advance their own causes. A San Francisco newspaper once wrote about the Filipinos and their fighting spirit, “The Filipinos are not conquered. Their spirit is not broken. Their capacity for resistance has not begun to be exhausted.” [1]

This photograph is captioned “Filipino Boy Scouts.” It is likely that the photographer, Samuel Shera, might be referring to the Philippine Scouts, who were recruited and trained by American forces during this time period, 1899-1902. The US used organizations like this to civilize the Filipinos by making them in their image, but never as American citizens nor as a self-governing people.

The role of the media was increasingly important during this time. Newspaper reports, photographs, letters from soldiers, soldiers’ testimonies, and political cartoons made many people question and criticize why the US was fighting in the Philippines, when the United States had similarly fought for its own independence. Filipinos resisted American occupation for much longer than anyone initially thought–and the US responded with brutal violence, torture, and burning entire villages.

Transcription of caption on reverse of image:

Filipino boy scout organizations sprang up like mushrooms some time ago. Americans called the governor-general’s attention to the fact that they were not boys at all but nearly all men and led by ex-insurrectos. They grew bold and talked about liberating their country from foreign tyrants. The governor put them out of commission

Discuss in Pairs: Close Reading Questions

- List five things you notice in this image. Based on these things, pick three adjectives to describe the scene in the image.

- Think about the adjectives you chose. What argument do you think this image is making about US involvement in the Philippines?

- Why do you think different kinds of media were so important during the war? How do different kinds of media (photos, newspaper articles, sketches, reports, etc.) convey different kinds of information?

- What is the role of media during a war?

Document 5: Strong Lines

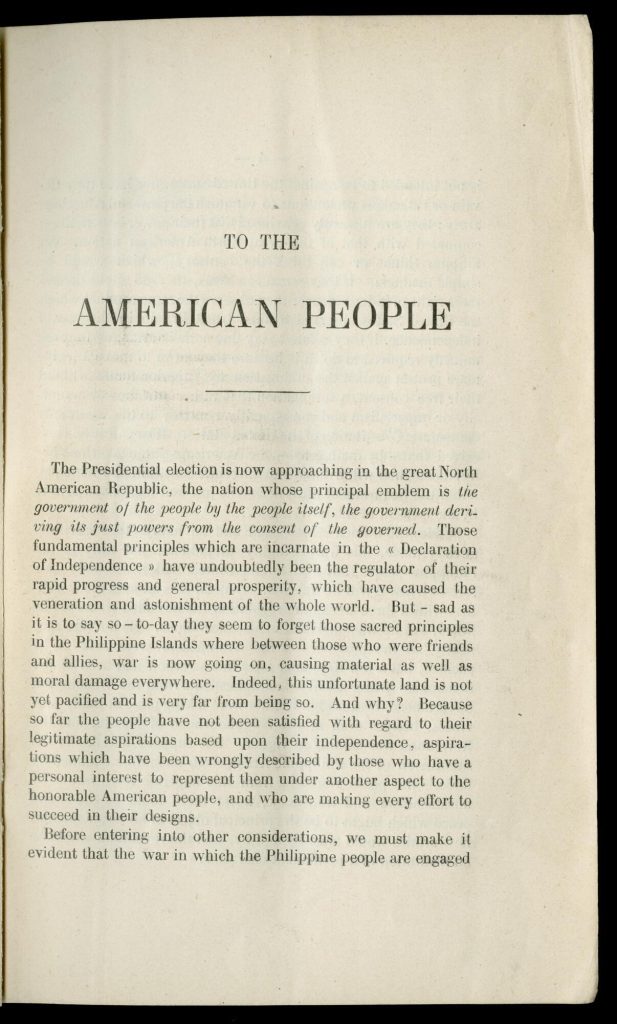

Filipe Agoncillo, “To the American People” (1900)

Document Context

Felipe Agoncillo was a Filipino lawyer who was to represent the Philippines at the Treaty of Paris. He went to Washington, DC to try and meet with President McKinley, but the president’s office refused. When he arrived in Paris, he sought to “[protest] against any resolutions that contrary to the Independence”[2] of the Philippines, but he found out there that the US sought to make a colony out of his homeland.

Strong Lines: Close Reading Questions

- What reasons does Agoncillo give for the case of Philippine Independence?

- Choose 1-2 strong lines (lines that stand out to you for any reason) and explain why they stand out.

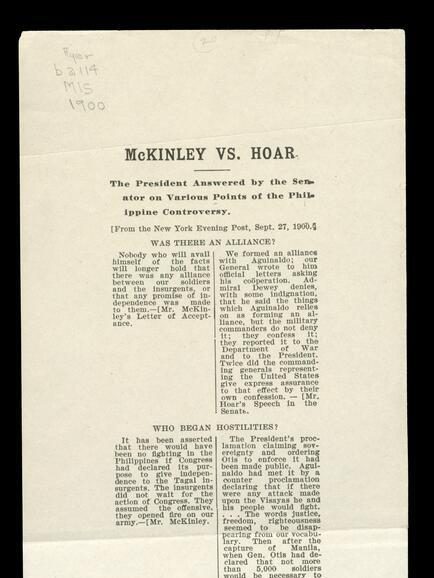

Document 6: Debate Questions

“McKinley vs. Hoar,” New York Evening Post (1900)

Document Context

In this broadside (sheet of paper with printing on one side) originally published in the New York Evening Post in 1900, you’ll see President McKinley’s responses to Senate questions on the left, and Senator George Hoar’s responses on the right. McKinley was pro-expansion, and in favor of pursuing imperial efforts in the Philippines. Hoar, however, was part of the Anti-Imperialist League that opposed the annexation of the Philippines.

American politicians and military men made up the Philippine Commission, which was tasked with establishing peace in the Philippines and reporting on the status of Filipinos, their educational and political systems, and how to govern them.

Debate Questions: Close Reading Questions

- In 2-3 sentences, summarize McKinley’s position on US imperialism in the Philippines. Do the same with Hoar’s position.

- What issues do they disagree on? Who should have won the debate? Explain your answer using ideas from the text.

- Write down 2-3 questions that you’d ask these politicians to debate.

Documents 7 & 8: The Cost of War

Documents from architect William E. Parsons’ time in the Philippines

Document Context

Emilio Aguinaldo was captured by American and Filipino troops in 1901, and he called for fellow Filipinos to lay down their weapons. After a bloody, restless war, President Theodore Roosevelt (elected after President William McKinley) declared a general amnesty on July 4, 1902. Over 200,000 Filipinos died of violence, famine, or disease during the war. Following the war, guerilla fighting still ensued, and the Americans fought the Moros (Filipino Muslims) in the southern part of the Philippines (called Mindanao).

To appeal to the American public, the US government brought Filipinos stateside and put them on performative tours and displays to inform white American audiences about their investment in the American side of the war. Filipinos were on display prominently at the St. Louis World’s Fair in April of 1904 and in other Philippine villages were constructed throughout the US. In the Philippines, the US set up colonial governments in different provinces, with former military leaders as new colonial governors. Many of these colonial governors had business interests in staying in the Philippines. One such businessman who held a public role in the Philippines was William E. Parsons.

In the documents here, you’ll see a personal account and business receipt from the office of Midwestern architect William E. Parsons, who was appointed by another famous Midwestern architect named Daniel Burnham to take over some his contracts in the Philippines. Burnham was an urban planner whose architecture was to reflect America’s growing status on the global stage and depict America’s greatness in its cities. Burnham’s buildings in Chicago (including on the 1893 World’s Fair), New York City, London, and San Francisco earned him a federal contract to expand Manila and Baguio in the Philippines. The receipt shows the government buildings, schools, hotels, parks, prisons, and schools that were built during his tenure as the Consulting Architect for the US government in the Philippines. Americans brought their colonial architecture to all aspects of Philippine life–they built their version of a modern Philippines.

The Cost of War: Close Reading Questions

- How does Parsons describe the Philippines, its government, and its people? Based on this tone, what do you think he thought of the Philippine civilians and their government?

- What items in Parsons’ list stand out to you or surprise you?

- Write your own receipt with items that show the cost of war. Add items that are more than material objects or ones that may be priceless.

Final Reflection & Discussion

Bring the class back together for a final discussion. Possible questions include:

- Why was the United States invested in the Philippines?

- What did the US and the Philippines each have to gain in this war?

- What is the role of media during a war? How can it shape public perception of the war?

Background

America pursued the Philippines to build its empire and to have a military outpost in the Pacific Ocean. Following the Battle of Manila Bay, when the United States defeated the Spanish fleet, Emilio Aguinaldo declared Philippine independence on June 12, 1898. A month later, on August 13, 1898, the Spanish agreed to a mock battle with the United States and then surrendered the capital city of Manila. The Spanish were outnumbered by Filipinos by land and the Americans by sea. They did not have a lot of troops in the Philippines because their empire extended into the Caribbean and across South America, so they saw the mock battle as an honorable way to surrender their 300-year-old colony to a more prepared and better armed US military. The battle also indebted the Filipinos to the US, because US naval power was crucial to forcing the Spanish to surrender.

In December of that year, commissioners from the US and Spain met in Paris to sign the Treaty of Paris, which revealed an act of international collusion and secrets. The Treaty of Paris formally ended Spain’s colonization of the Philippines, but it did not recognize Philippine independence. Instead, the United States paid Spain $20 million to turn former Spanish occupied lands into its own American colonies: Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba, and the Philippines. This was part of broader US colonial expansion in the Pacific. The US had overthrown the Hawai’ian monarchy and claimed its land as its own that same year.

Emilio Aguinaldo was sworn in as the first President of the Philippine Republic in 1899, but the United States did not recognize the nation as an independent country. Filipinos found themselves fighting against the United States, who were once their allies against Spain. They formed the Philippine Liberation Army and guerrilla warfare continued throughout the Philippines until 1902.

At the same time, the American public was not aware of the horrors, casualties, and resources put into the war with the Philippines. Then in 1898, US President William McKinley issued orders for the US Army to occupy the Philippines, which made US policy on the Philippines a major political issue. The US Senate debated “The Philippine Problem:” whether or not they would allow the Filipinos self-government or attempt to Americanize them. Filipinos insisted on their freedom from any occupying country, and American allies such as the Anti-Imperialist League advocated to stop American imperialism from becoming law and action.

American teachers, scholars, and explorers also helped advance US imperialism in the Philippines. In 1901, six hundred American teachers called the Thomasites were recruited to teach in the Philippines and arrive on the USS Thomas. The Thomasites departed from San Francisco, docked in Hawaiʻi for fuel, and worked in the Philippines–some stayed for up to twenty years. Although the Philippines already had an educational system that preceded the American and Spanish systems, the Thomasites became involved with schoolhouses that the Spanish had set up. Their work as educators served the imperial vision of assimilating Filipinos into American culture and raising a young generation of followers. [3] They taught American values and emphasized skills and hobbies such as sewing, playing baseball, learning and speaking English, and practicing Christianity. American explorers, reporters, business owners, and university professors such as the “Michigan Men” also led expeditions where they collected animals, plants, and Philippine cultural objects to bring back to the United States.

About the Author

Janice Lobo Sapigao (she/her) is a Filipina American writer from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is a daughter of immigrants who grew up in an intergenerational house with twelve people. She authored the poetry collections like a solid to a shadow (Nightboat Books, 2022) and microchips for millions (PAWA, Inc., 2016). She contributed three entries to The SAGE Encyclopedia of Filipina/x/o American Studies. She is a 2023-2026 Lucas Arts Fellow at the Montalvo Arts Center and a Heid Fellow at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, studying the Philippine History Special Collection. She was a Visiting Scholar at the Newberry Library, the 2020-2021 Santa Clara County Poet Laureate, a Poet Laureate Fellow with the Academy of American Poet, and a tenured Associate Professor of English at Skyline College. She is an avid reader, an introvert, and an earrings collector. She is working on a novel.

[1] San Francisco Call. May 9, 1900.

[2] “Official protest against the Paris Peace Treaty.” Newsletter signed by Felipe Agoncillo (1859 – 1941), Filipino lawyer representative to the negotiations in Paris that led to the Treaty of Paris (1898), ending the Spanish–American War, protesting against the resolutions agreed at the Peace Conference in Paris, and questioning the right to Spain to decide about the future of the Philippines. December 12, 1898.

[3] “The Philippines and the University of Michigan, 1870-1935.” Michigan in the World.

Illinois Social Science Standards

This lesson supports the following standards from the Illinois Learning Standards for Social Science:

Evaluating Sources and Using Evidence: SS.9-12.IS.5: Gather and evaluate information from multiple primary and secondary sources that reflect the perspectives and experiences of multiple groups, including marginalized groups.

History:

- SS.9-12.H.10: Identify and analyze the ways in which marginalized communities are represented in historical sources and seek out sources created by historically oppressed peoples.

- SS.9-12.H.14: Analyze the geographic and cultural forces that have resulted in conflict and cooperation. Identify the cause and effects of imperialism and colonialism.

Ethnic Studies/Asian American Studies Theme – TEAACH ACT

- This lesson connects to the ethnic studies theme of power and oppression from the Asian American Studies Curriculum Framework (Asian American Research Initiative, 2022), and the Illinois School Code via HB 376 T.E.A.A.C.H. Act. Students will consider war, migration, and imperialism as contexts shaping citizenship and racialization.

Historical Thinking Skills

This lesson will facilitate student proficiency in historical significance, one of Seixas’ historical thinking skills (Seixas & Morton, The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts, 2013). Educators improve student familiarity with the criteria for historical significance. Students consider how events, people, or developments have historical significance if they resulted in change.

This lesson centers the politics of historical memory as late Filipina American Historian, Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, described as “the ways in which we remember, and forget, the history of the community” (Mabalon, “Introduction: Rememingering Little Manila.” Little Manila is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California, 2013). Mabalon’s work concerns the historical process of racialization, cultural transformation, and memory.

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the lesson “US Imperialism in the Philippines”

- Sources used in this lesson

- Student vocabulary and source analysis handout

- Vocabulary definitions

Related Newberry Resources

More about Teaching Ethnic Studies

- California State Board of Education, Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum (2022)

- Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Coalition, Glossary