Themes

American Imperialism

Empire

Spanish Colonialism

Periods & Events

Philippine-American War

Philippine Revolution Spanish-American War

Skills & Documents

Close Reading

Historical Memory

Postcards

Compelling Question:

- What led to the Philippine-American War?

Lesson Questions (Supporting Questions):

- What is the difference between colonialism, imperialism, and empire? What did each one mean for America and the Philippines?

- How did the United States’ mistreatment of non-white peoples (Native Americans, Black Americans, Chinese Americans, Eastern European and Jewish groups) lead to the age of imperialism in the Philippines?

Lesson Objectives:

- Students will be able to evaluate the causes and impacts of war from American and Filipino perspectives by analyzing primary source materials.

Materials – Documents available for in the Downloads tab

- Access to a computer and projector

- Sources:

- Newberry Library catalog note for Carta de Fr. Gaspar de San Ag[ustí]n (online here)

- Gramática hispano-ilocana / compuesta por el P. Fr. José Naves (high-resolution version)

- José Rizal Bust (high-resolution version)

- Charles A. Davis postcard (high-resolution version)

- Student vocabulary & source analysis handout

- Supplementary Sources:

- Map of the Philippines (option from the Newberry)

- The Forbidden Book by Abe Ignacio, Enrique de la Cruz, Jorge Emmanuel, and Helen Toribio

- Vestiges of War edited by Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis H. Francia

The Philippine Revolution by the Library of Congress - Unknown Soldiers Podcast by James Houser

Process

More background information on the Philippine-American War is provided

in the Background section below. Handouts with close reading questions and activity workspace are provided in the Downloads tab.

- Warm-Up Writing Activity: (5 minutes)

- Ask student to free write on the prompt: What do you know about war, and how does it make you feel?

- Process Writing Discussion: (5 minutes)

- Ask 2-3 students to share their writing with the class.

- Say: “It’s okay if your ideas change. We know you are just starting writing and thinking about this topic.”

- Assessing Prior Knowledge in Pairs (10 minutes)

- Display the following key terms for students and have them discuss their understandings of the meanings: annexation, capitalism, colonialism, empire, imperialism, racialization, war. A student vocabulary worksheet and definitions are provided in the Downloads tab.

- Students can look up unfamiliar terms if needed. Useful resources are the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium Guide and the California Department of Education Model Curriculum Guide.

- Have a class discussion about these terms and solicit student responses about definitions for each. Formal definitions should be copied by students and/or made available on display for accessibility. (5 minutes)

- Source Set and Close Reading Activities:

- Document 1: Teacher Models Close Reading (10 minutes)

- Document 2: Discuss in Pairs or Small Groups (10 minutes)

- Documents 3 & 4: Individual Reflection & Analysis (10 minutes)

- Document 5: Create Your Own Postcard (20-30 minutes)

- Optional: Document Type Analysis Activity

- Final Reflection/Discussion (10-15 minutes)

Document 1: Teacher Models Close Reading

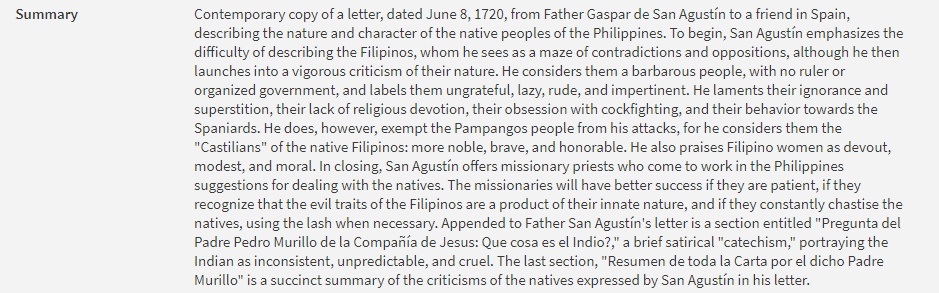

Catalog Summary for Letter by Gaspar de San Agustín, Newberry Library Catalog

Document Context

Because this contextual note was written by Newberry librarians to help researchers understand San Agustín’s letter, it is a secondary source. Primary sources are original documents written at the time of an event. Secondary sources often contain primary source materials but are later interpretations of a primary source. Most sources in the Newberry archives contain these notes. They can be tools that students use as they browse through a library catalog, especially for culturally sensitive materials.

This contextual note summarizes how Spanish friars defiled and dehumanized Filipinos before the age of American imperialism began. It will be important to discuss the vocabulary words for this lesson alongside the reading of this note, with attention to colonialism and empire.

After 300 years of Spanish rule, the Catholic Church is a remnant of Spanish colonization that is still widely present to this day in the Philippines. The Philippines became the most Christianized country in East Asia, and the friars, or priests, of the Catholic Church were also government officials during the colonial period. The Catholic friars ruled various provinces of the Philippines, and they controlled state entities such as police, taxes, and health systems and incorporated Catholic traditions into Indigenous practices.

Teacher Modeling: Close Reading Questions

Have students read the catalog contextual note, then discuss the following questions as a group:

- What are your reactions to the summary of this letter?

- Based on this summary, how does San Agustín describe Filipinos? Use specific examples from the text.

- Look back at our definitions of colonialism, imperialism, and racialization. Where do you see elements of these three ideas in San Agustín’s ideas?

- Based on your observations, why do you think Catholic Church and Spanish state worked together?

- What questions does this summary raise for you? Where could you go to get answers to these questions?

Document 2: Discuss in Pairs or Small Groups

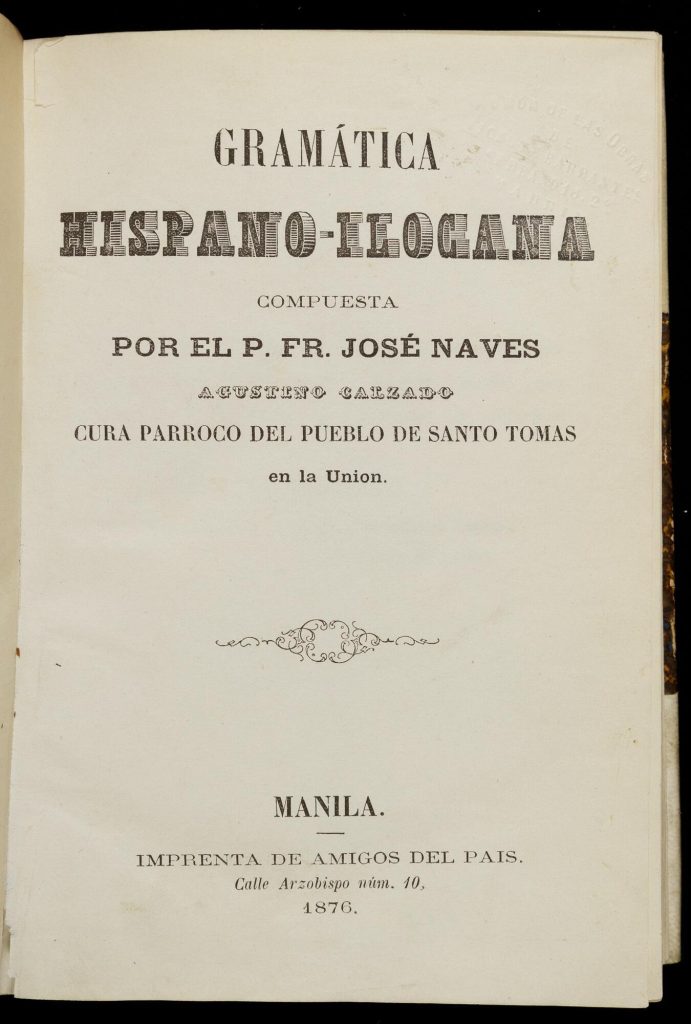

Gramática hispano-ilocana (1876)

Document Context

The Philippines is made up of hundreds of ethnolinguistic groups across 7,000 islands. These pages from a Spanish-Ilocano dictionary were written by a Spanish priest named José Naves. Many Filipinos did not learn Spanish, and a lot of them spoke their home languages–Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, and more. Ilocano is a language spoken mostly in Northern Luzon, which is the northernmost part of the Philippines. Though the Spanish mostly controlled Manila, which is on the eastern shore of Manila Bay, priests were assigned to different regions and were often the only Spaniards in certain areas or towns. They created dictionaries like this for Catholic missions and schools. Other dictionaries were compiled by early white European and American navigators and collectors who were curious about the Philippines and documented their observations of Indigenous Filipinos.

Discuss in Pairs or Small Groups: Close Reading Questions

- Who do you think used these dictionaries?

- Why was it important for Spaniards to learn Ilocano? Why was it important for Ilocanos to learn Spanish? How are the different communities’ reasons similar, and how are they different?

- Look back at our definitions of colonialism and imperialism. Do you see elements of these ideas in the reasons Spanish speakers and Ilocano speakers learned each other’s languages?

Documents 3 & 4: Individual Reflection and Analysis

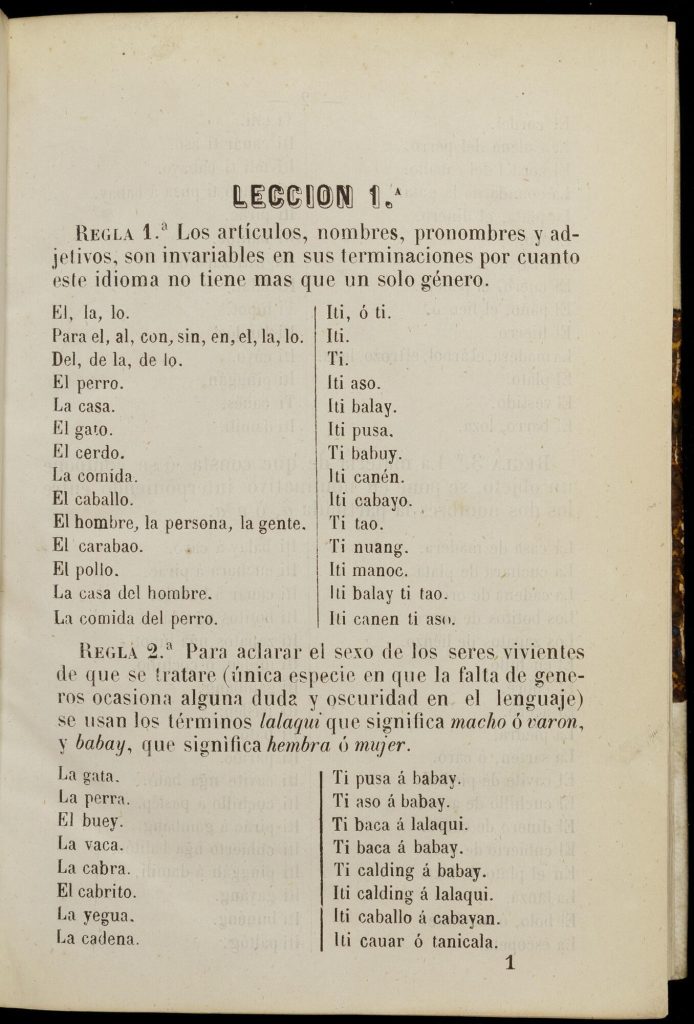

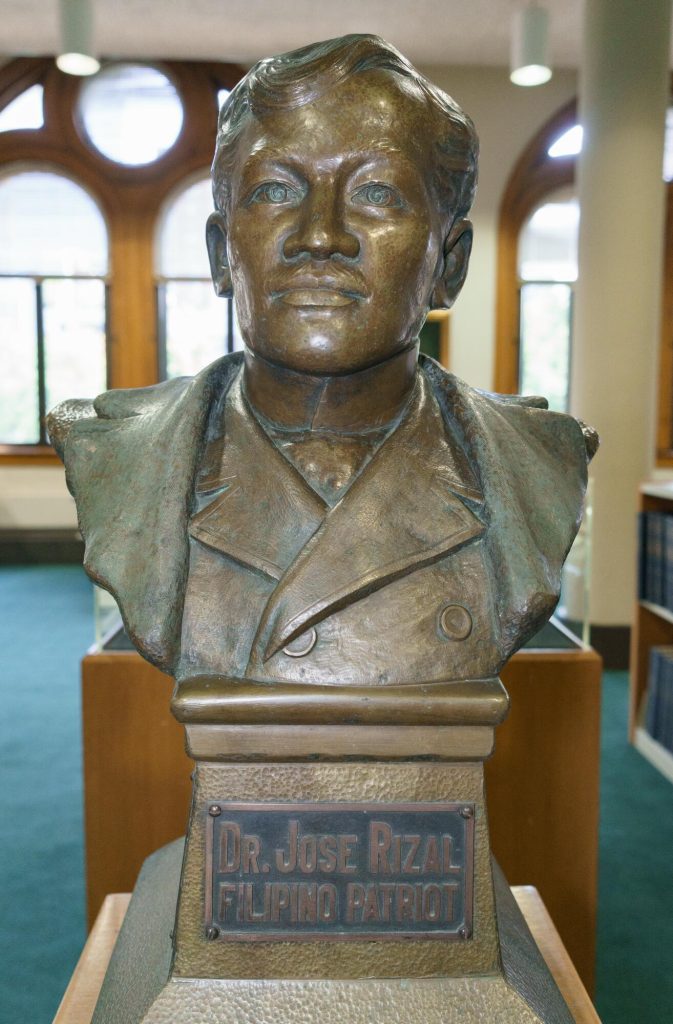

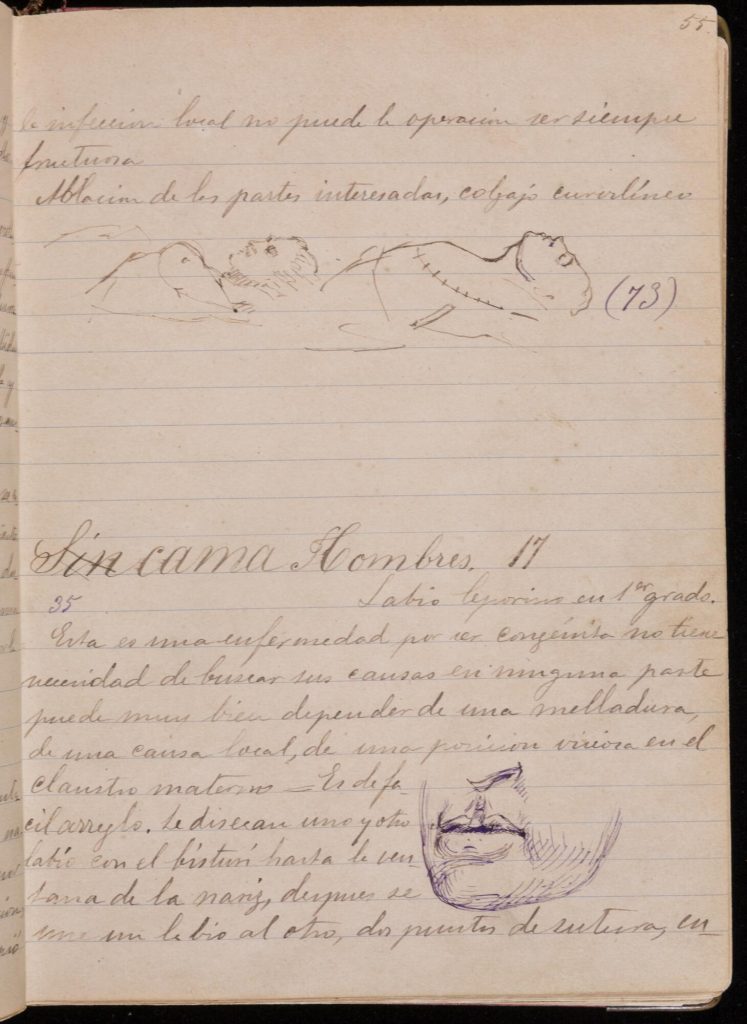

José Rizal Bust (1927) and Clinica medica (1881)

Document Context

José Rizal (1861-1896) is considered a national hero of the Philippines. He was an ilustrado (in Spanish, “enlightened one”), part of an educated and wealthy class that studied in the Philippines and Spain and wanted to take part in governing their country. Most ilustrados advocated for civil rights, political reform, and the end of priests as rulers. Ironically, manyilustrados wanted Spanish citizenship, and wanted the Philippines to be considered a province of Spain for legal and economic equality. Rizal emerged as a well-known ilustrado who wrote two notable books Noli Me Tangere (in Latin, “Touch Me Not”) and El Filibusterismo (in Spanish, “The Subversive”) that influenced people to think about independence from Spain. Rizal’s ideas were used to galvanize Filipinos across lower, working, and poorer classes to join a secret revolutionary group called the Katipunan, founded by another Philippine revolutionary leader named Andres Bonifacio. The Spanish authorities discovered this group, and as a result, ordered Rizal’s death via a Spanish firing squad in 1896. His execution symbolized the pain of the Filipinos and the desire for independence that led to the Philippine Revolution (1896-1899). Learn more about Rizal and the Clinica medica here.

Individual Reflection: Close Reading Questions

- What makes Rizal a national hero?

- Why do you think the Rizal Club of Chicago donated a bust of Rizal to a public research library like the Newberry?

- Look at the pages from Rizal’s notebook. List five things you observe.

- Even if you can’t read any of his writing, what can you guess about Rizal from your observations of his notebook?

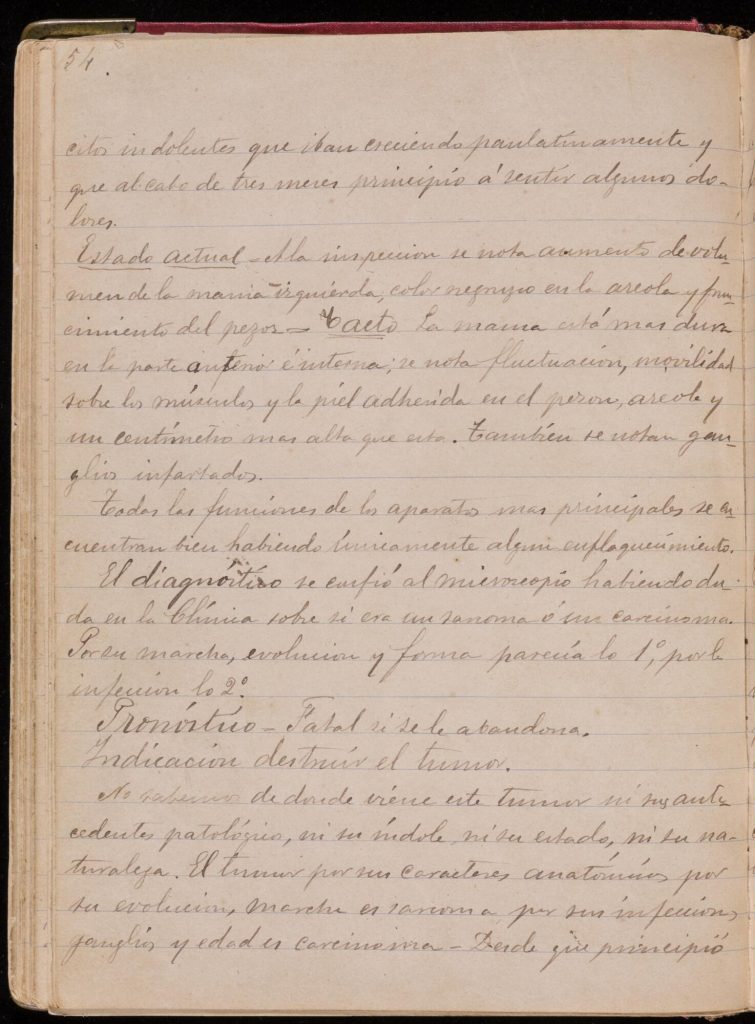

Document 4: Create Your Own Postcard

Charles A. Davis Postcard (1900)

Manila, P.I.

Oct. 1, 1900

Dear Bess,

Uncle Sam does not approve of this card, so enclose in envelope. Mailed the letters and two pkgs today. Love to all.

Yours lovingly,

Charlie.

Document Context

This postcard was written by Charles A. Davis, a young American who left Cincinnati on May 22, 1900, to take up a job as a court reporter in Manila, after the Americans had taken control of the Philippines. Not much is known about him, but he often wrote home to his wife, Bess.

Pictured on the postcard is Emilio Aguinaldo (1869-1964), a military leader who fought and won battles against the Spanish. Aguinaldo became the first President of the Philippine Revolutionary Government. He was not an ilustrado, but he was a member of the Katipunan. When the Spanish found him, he signed the Biak-na-Bato Pact in 1897, which was an agreement between himself and the Spanish to stop the fighting. He was exiled to Hong Kong, where he took more time to plan out the route to Philippine independence. He returned to the Philippines in May 1898, immediately after the US defeated the Spanish Pacific fleet in the Battle of Manila Bay. He worked with US leaders to fight against the Spanish, and then sought to establish a free Philippines. When the US refused to acknowledge their independence, the Filipinos declared war on the US.

Create Your Own Postcard: Close Reading Questions

- Take a close look at the postcard written by Charles A. Davis. Why do you think Uncle Sam (a symbolic, cartoon figure for the United States) would not approve of it?

- Whose freedom and power was the US fighting for during the Spanish-American War and later during the Philippine-American War?

- Create your own postcard with an image or scenario that reflects a current event or what you wrote about in your warm-up writing activity. Your event should be something that you think will be discussed in the future, 20 to 30 years from now. Then, add a short letter addressed to someone you know.

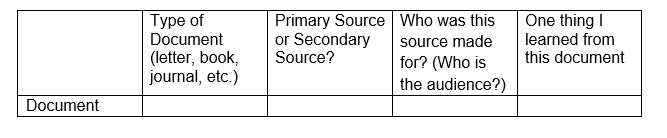

Optional: Document Analysis Activity

The documents in this lesson represent a range of source types. Each type gives students different information about Philippine history, showing students that different kinds of sources tell different kinds of stories. Have students fill out the chart below (full version in the student handout in the Downloads tab) to explore these differences, then discuss the questions below.

- Look at your list of things you learned. What kind of information did you get from each source? How are the kinds of information different?

- Which source do you think you learned the most from? Why?

- What did this activity tell you about why researchers and historians consult multiple kinds of sources?

Final Reflection & Discussion

Bring the class back together for a final discussion. Possible questions include:

- What caused Filipinos to fight for their independence?

- How did Filipinos fight for their independence?

- How do researchers use different kinds of sources to get different kinds of information?

Background

The Philippine-American War (1899-1902) is one of the United States’ least-known wars. Its impact is still felt today, though, as it was the first time the United States pursued a war overseas in Asia. After fulfilling the artificial concept of Manifest Destiny–the colonial idea that it was the divinely ordained right of the United States to expand its borders to the Pacific Ocean and beyond–the United States joined the Age of Imperialism in the late 19th century with the Spanish-American War.

The Spanish-American War of 1898 preceded and led to the Philippine-American War. It originated in Cuba, as Cubans struggled for their independence from Spain beginning in 1895. When the American battleship, the USS Maine exploded in the harbor in Havana, Cuba in 1898, it was unclear why it sunk, but many suspected Spain. The Cuban rebellion, the sunken battleship, and decreased US investment in Cuba led the United States to demand Spain’s withdrawal from the island. Soon afterwards, Commodore George Dewey of the United States Navy sunk a Spanish fleet in Manila Bay in the Philippines. Spain’s defeats led to its dispossession of its colonies, and the Philippine Revolutionary Government declared their independence from Spain in 1898. But the United States positioned itself to take Spain’s place. Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were annexed from Spain by the United States for $20 million. In 1899, the United States responded to the declaration of Philippine independence with 70,000 troops and three years of brutal fighting against the Filipinos’ poorly armed, but popular, army in order to crush the newly established republic (Holm, 2013).

To understand US actions in the Philippines, it is important to understand what was taking place in the United States socially and politically at the same time. From 1860 to the start of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the United States began defining its identity to itself, its people, and the global stage. This included a blueprint for the inclusion of non-white populations: they were integral to the nation, but only because they were viewed as inferior (Espiritu, 2013).

Before the Philippine-American War, the United States passed legislation in service of white settlers, manufacturing companies, and railroad companies, in order to occupy the land it had forcibly taken from Indigenous peoples in the west. Eastern European, non-Protestant, and Jewish migrants to the United Sates were subject to nativism, discrimination, and forced English-only instruction. Native, Black, and Asian populations were left out of the economic boom that came with industrial expansion, and events such as the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), the massacre at Wounded Knee (1890), the passing of Jim Crow laws (1890s), and the racism and classism in the growing women’s suffrage movement kept these groups physically marginalized and politically disenfranchised.

About the Author

Janice Lobo Sapigao (she/her) is a Filipina American writer from the San Francisco Bay Area. She is a daughter of immigrants who grew up in an intergenerational house with twelve people. She authored the poetry collections like a solid to a shadow (Nightboat Books, 2022) and microchips for millions (PAWA, Inc., 2016). She contributed three entries to The SAGE Encyclopedia of Filipina/x/o American Studies. She is a 2023-2026 Lucas Arts Fellow at the Montalvo Arts Center and a Heid Fellow at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, studying the Philippine History Special Collection. She was a Visiting Scholar at the Newberry Library, the 2020-2021 Santa Clara County Poet Laureate, a Poet Laureate Fellow with the Academy of American Poet, and a tenured Associate Professor of English at Skyline College. She is an avid reader, an introvert, and an earrings collector. She is working on a novel.

Illinois Social Science Standards

This lesson supports the following standards from the Illinois Learning Standards for Social Science:

Evaluating Sources and Using Evidence: SS.9-12.IS.5: Gather and evaluate information from multiple primary and secondary sources that reflect the perspectives and experiences of multiple groups, including marginalized groups.

History:

- SS.9-12.H.9: Analyze the relationship between historical sources and the secondary interpretations of them.

- SS.9-12.H.10: Identify and analyze the ways in which marginalized communities are represented in historical sources and seek out sources created by historically oppressed peoples.

- SS.9-12.H.14: Analyze the geographic and cultural forces that have resulted in conflict and cooperation. Identify the cause and effects of imperialism and colonialism.

Ethnic Studies/Asian American Studies Theme – TEAACH ACT

- This lesson connects to the ethnic studies theme of power and oppression from the Asian American Studies Curriculum Framework (Asian American Research Initiative, 2022), and the Illinois School Code via HB 376 T.E.A.A.C.H. Act. Students will consider war, migration, and imperialism as contexts shaping citizenship and racialization.

Historical Thinking Skills

- This lesson centers the politics of historical memory as late Filipina American Historian, Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, described as “the ways in which we remember, and forget, the history of the community” (Mabalon, “Introduction: Rememingering Little Manila.” Little Manila is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California, 2013). Mabalon’s work concerns the historical process of racialization, cultural transformation, and memory.

- This lesson will facilitate student proficiency in historical significance, one of Seixas’ historical thinking skills (Seixas & Morton, The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts, 2013). Educators improve student familiarity with the criteria for historical significance. Students consider how events, people, or developments have historical significance if they resulted in change.

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the lesson “Causes and Impacts of the United States’ War with the Philippines”

- Sources used in this lesson

- Student vocabulary and source analysis handouts

- Vocabulary definitions

Related Newberry Resources

More about Teaching Ethnic Studies

- California State Board of Education, Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum (2022)

- Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Coalition, Glossary