Transcriptions of the documents in this essay coming soon.

Introduction

All North America was Indian country prior to European settlement in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The conventional narrative holds that Indigenous peoples were overwhelmed by a wave of European conquest over the subsequent centuries. While the history of Native peoples in North America was marked by tragedy, the full story is much more complicated. In his book Facing East from Indian Country, historian Daniel Richter encourages us to take on an Indigenous perspective and insists that, from their vantage point, early American history is better understood. He asks that we consider the “stories of North America during the period of European colonization rather than of the European colonization of North America.” Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Indigenous groups encountered Europeans and the diseases, environmental changes, and economic disruptions that followed their arrival. Nevertheless, they creatively adapted to such circumstances and continued to influence the course of history in the process. This digital collection seeks to view events from their perspective and considers the ways in which Native nations experienced and shaped history in the late 1700s.

The late eighteenth century was marked by imperial competition, as European powers vied for control of land and resources around the globe. The period has also been characterized by historians as the Age of Revolution, which witnessed the spread of democratic ideas and new political institutions in both America and Europe. Until recently, Indigenous peoples have been left largely out of the story. Students of history should avoid thinking of Indigenous peoples as merely passive victims of European wars. They were, in fact, active participants in a tumultuous period featuring both external and internal tensions. They created a space for themselves amid competition between European empires. Alliances shifted throughout and decisions made by Indigenous actors profoundly shaped events, sometimes with global ramifications. Tracing changes over time from the perspective of American Indians will aid us immensely in understanding this complicated process.

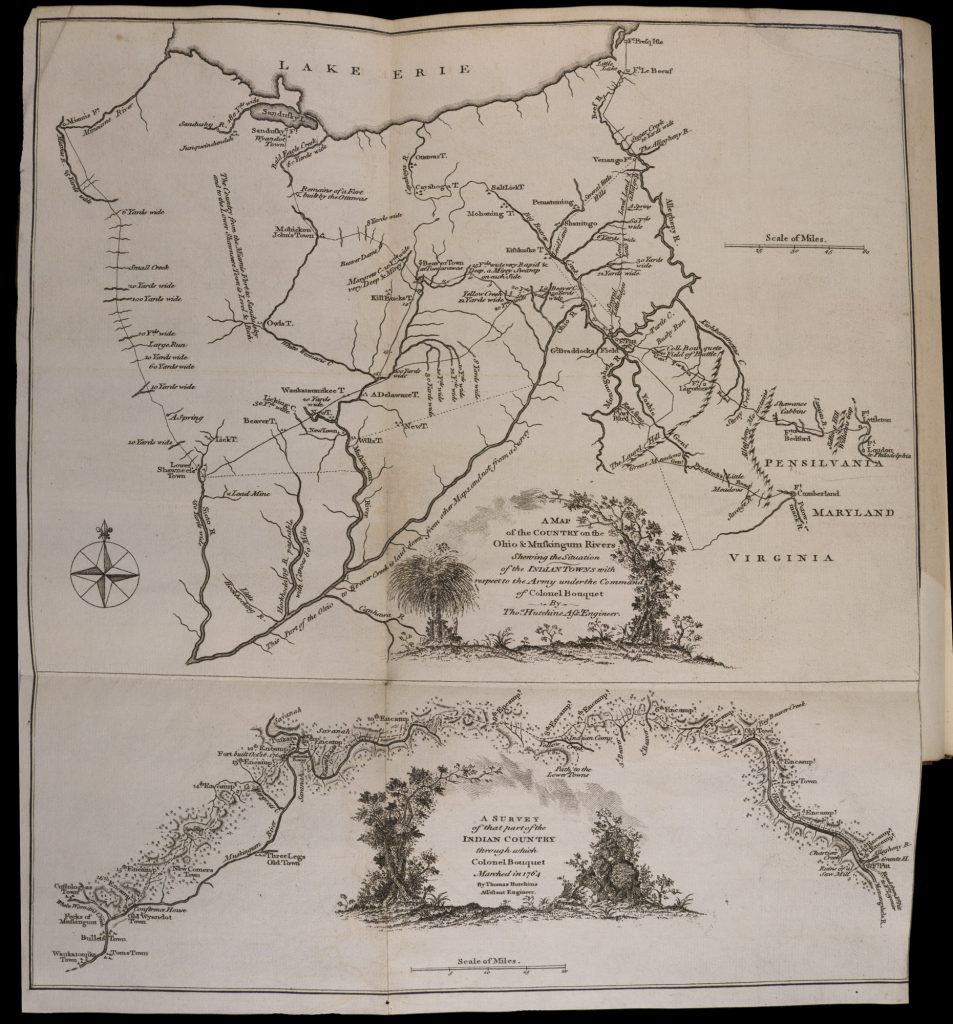

Fortunately, the Newberry Library has rich holdings related to Native history during the late eighteenth century. This digital collection places Native nations and leaders at the center of the action and demonstrates the important roles they played. From the Seven Years’ War through the American Revolution, they both resisted and adapted to the presence of whites in North America while also navigating internal tribal relationships and histories that predated contact with Europeans. The sources in this collection reflect this complex process as it unfolded from roughly 1750-1783. Maps reflect the shifting borders and contested territories of the time, records of important conferences between Native peoples and others demonstrate the delicate balance of power and changing alliances, and finally letters from the period exhibit the efforts to communicate even amidst the chaos of imperial warfare and revolution.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- What challenges did Native nations face in their interactions with Europeans and European colonists? How did imperial politics and economics shape this relationship? What were the primary goals of the various groups involved?

- What strategies did Indigenous leaders employ in dealing with these challenges? How did Indigenous and European approaches differ? How were they similar? How was the language of kinship used by both groups?

- What can we learn about Indigenous cultures by examining their interactions with Europeans during the late eighteenth century? How were the cultures and practices of various groups shaped by these interactions?

The Middle Ground

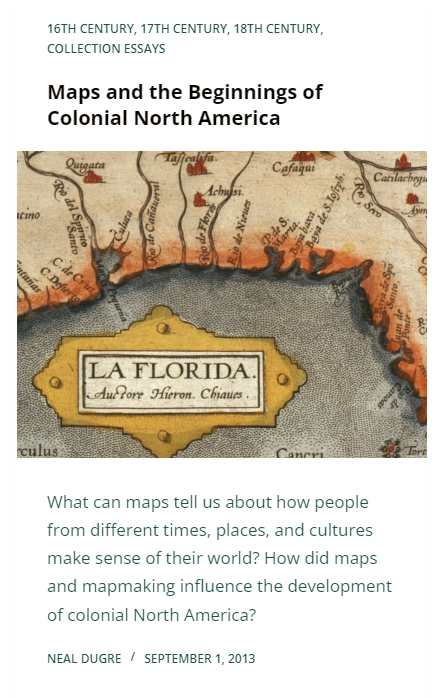

By the eighteenth century, England had established successful colonies in North America on the Atlantic coast and sought to expand further inland. The French had also established a presence in the region but generally sought to profit from trade with Native nations rather than through the extensive acquisition of land. France was particularly active in the Great Lakes region and, as the English continued to spread west, the two imperial rivals increasingly clashed. In his classic study The Middle Ground (1991), historian Richard White argued that in the first half of the eighteenth century a “middle ground” emerged that was marked by mutual accommodation between Native groups and Europeans in the Great Lakes region. A delicate balance of power developed as Algonquian-speaking peoples negotiated space between competing European powers, often effectively playing one off the other. During this period, Algonquian nations established a relationship with the French that positioned the French governor as a “father” who was responsible for mediating conflicts, dispensing gifts, and offering protection. Both groups offered a degree of cultural accommodation that contributed to stability for a time.

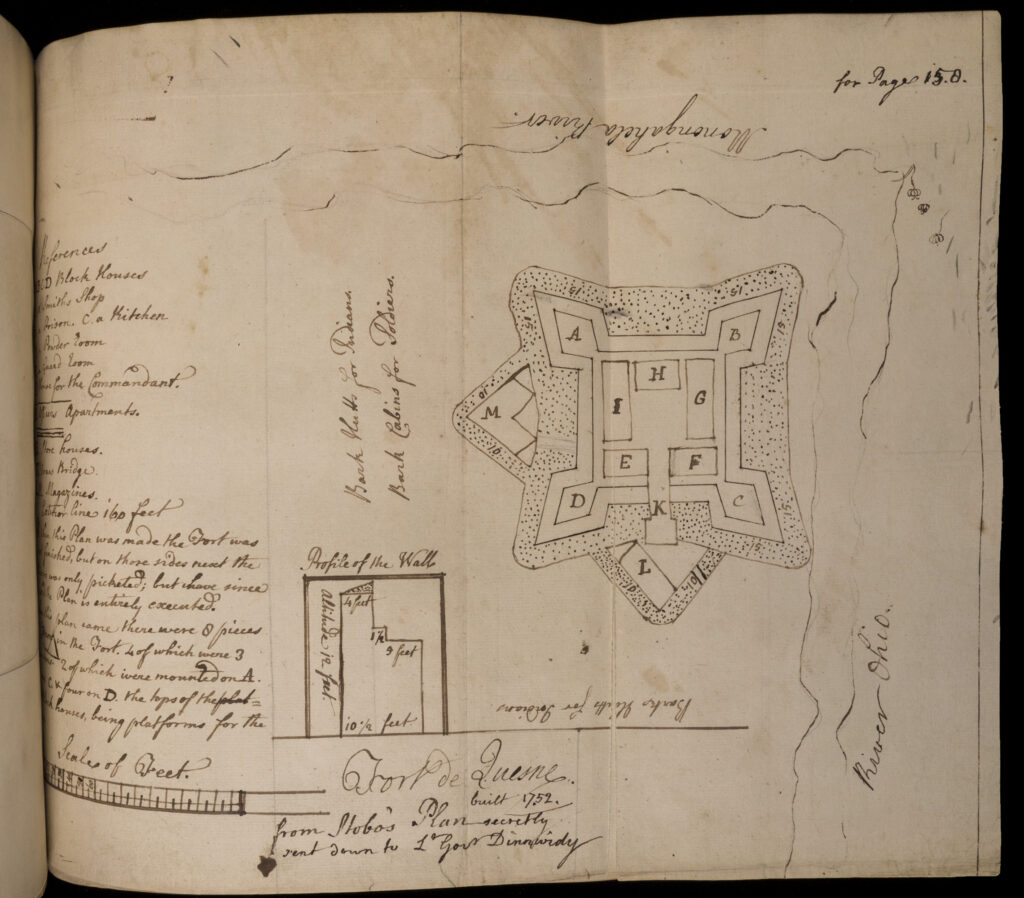

The middle ground began to break down as the British expanded their footprint in the region. By the mid-eighteenth century, English land speculators had set up forts in the Ohio Valley and the territory became hotly contested. Native nations in the region, including the Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, Wyandot, and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois), aided the French in expelling the English but also helped to spark what Winston Churchill called the “first world war.” The Seven Years’ War involved every European power, numerous Native nations, and saw conflict as far afield as India and the Philippines. At its conclusion, the British reigned supreme and aggressively asserted influence in North America. British hegemony was severely challenged by the American Revolution, which also spelled doom for the middle ground model of interaction. Americans were quick to fill the power vacuum and violent clashes between white settlers and Indigenous people set the tone for relations in the nineteenth century.

Questions to Consider:

- What does this map reveal about Indigenous and French settlement patterns in the Great Lakes region?

- What benefits did control of the region offer to Indigenous, French, and British groups?

Native Nations in an Imperial World

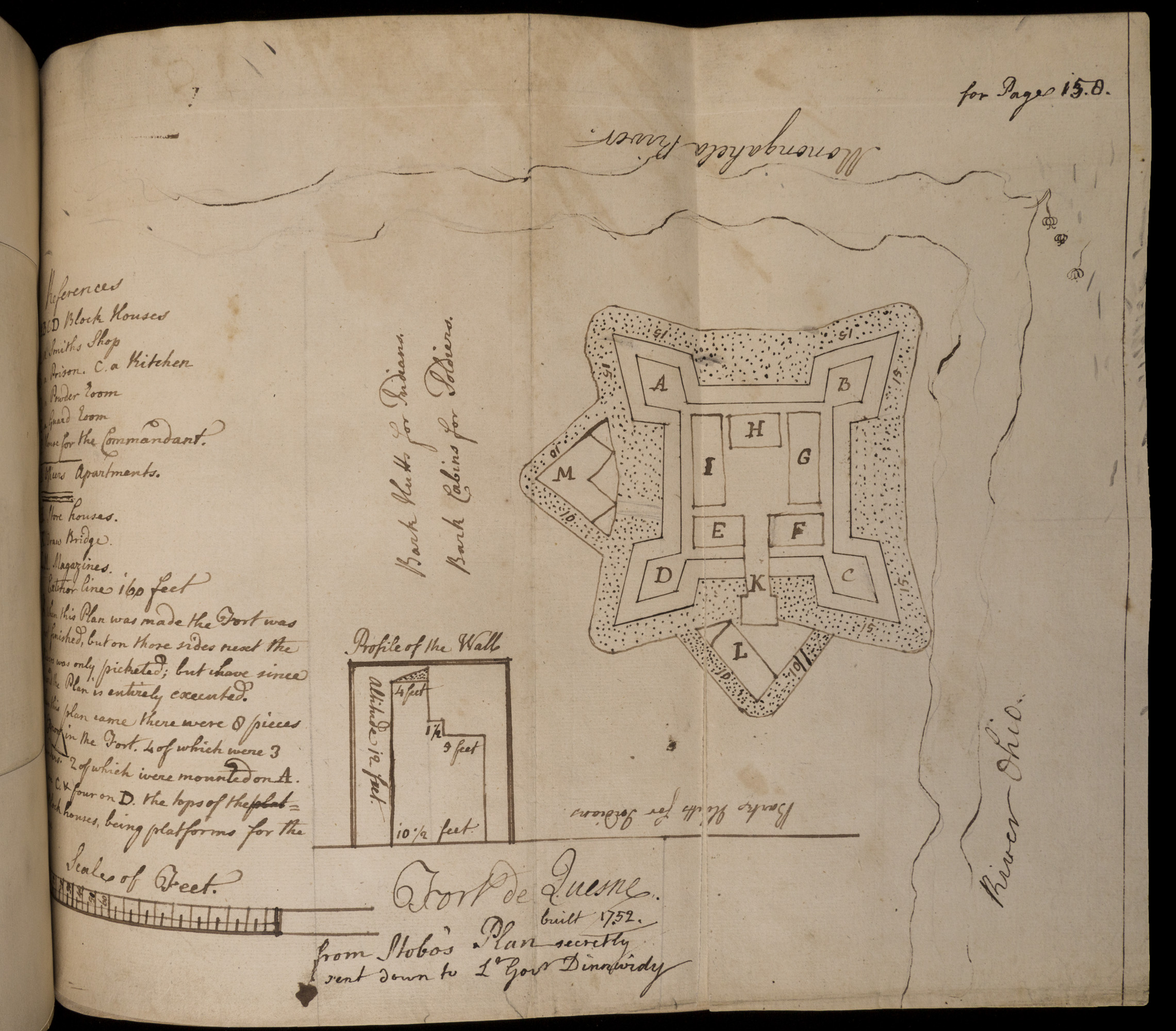

The French established several forts in the 1750s as a buffer against perceived British expansion in the Ohio Valley and to influence their Indigenous allies in the region. One of these was Fort Duquesne near present day Pittsburgh. In 1754, a Seneca chief named Tanacharison (Half King) sent word of the development to British allies in Virginia, who subsequently sent a band of militiamen commanded by a young George Washington to drive the French out. Assisting the Virginia soldiers was a delegation of Seneca warriors. A skirmish broke out near Fort Duquesne and a detachment of French diplomats was killed by the Senecas. Fearing retaliation from the French, Washington built a fortification nearby called Fort Necessity. There he lost most of his men in battle and was forced to surrender, signing a statement admitting that he had assassinated a French diplomat. The British responded by sending 3,000 troops to the colonies under General Edward Braddock. A combination of French, Native, and Canadian troops employed guerilla war tactics and defeated Braddock in one of the earliest battles in a conflict that would be fought on multiple continents. Washington, then Braddock’s aide, narrowly escaped death on the battlefield.

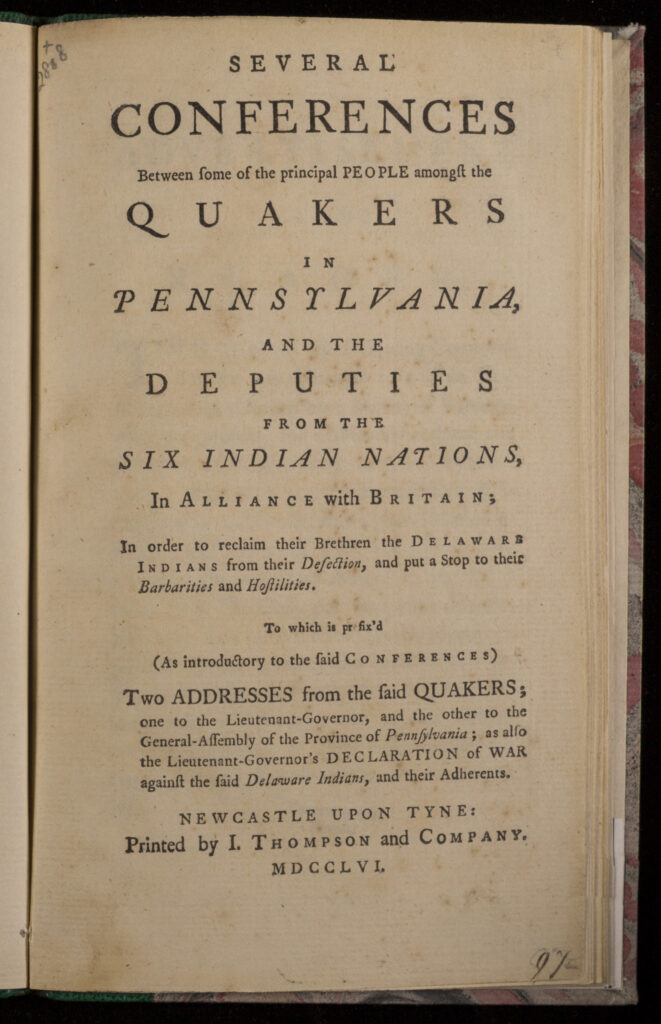

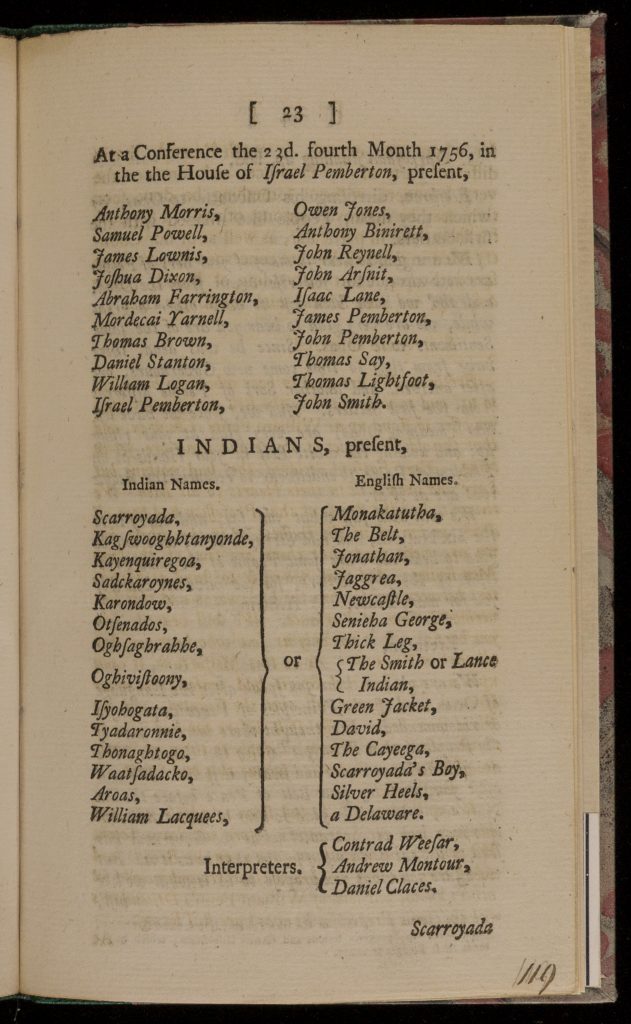

Selection: Ireael Pemberton, Several conferences between some of the principal people amongst the Quakers in Pennsylvania, and the Deputies from the Six Indian Nations (1756).

From the start, Native nations played important roles in the conflict. The war had many names. The British call it the Seven Years’ War, those in the United States usually refer to the French and Indian War, and French Canadians call it La Guerre de la Conquête (The War of Conquest). Native nations that allied with the French similarly characterized the war as one of British aggression. Among these were the Lenape who, despite previous ties to the British, hoped to prevent further British encroachment into their territory along the Delaware River. The governor of Pennsylvania declared war in 1756, calling the Delaware “Rebels and Traitors to His most Sacred Majesty.” Native nations allied with the British, including the powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy, hoped to benefit economically from British control of the Ohio Valley and the opening of trade routes that had been cut-off by rivals in the region.

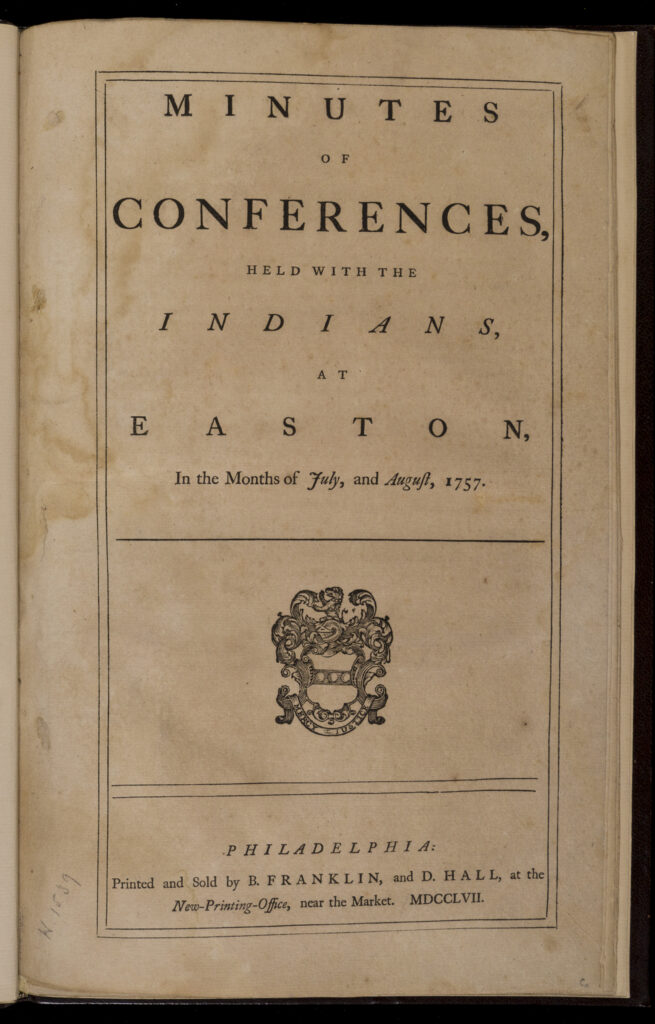

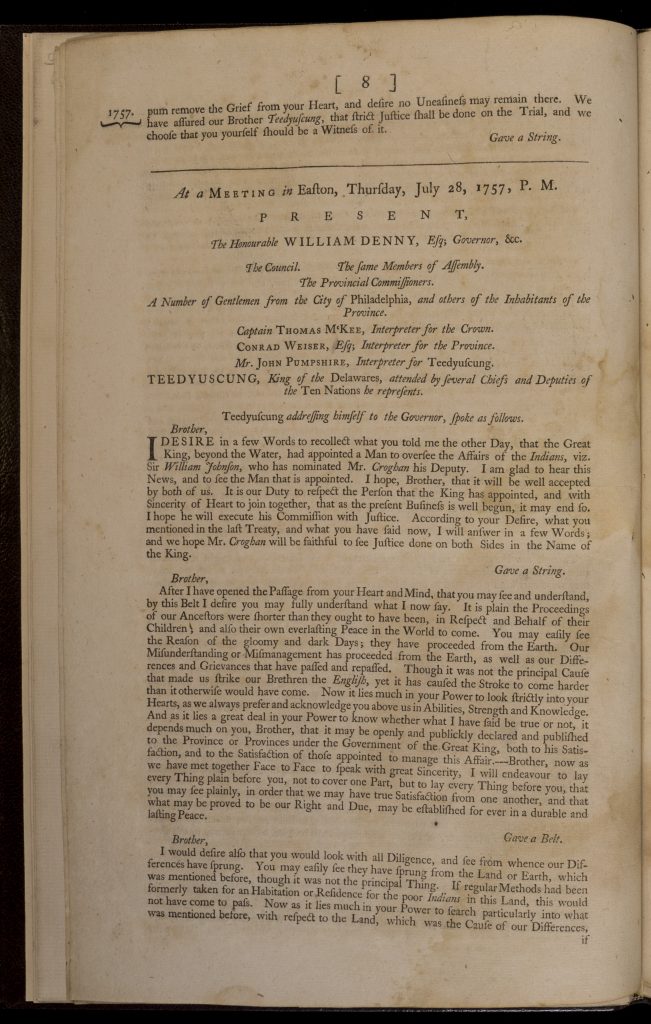

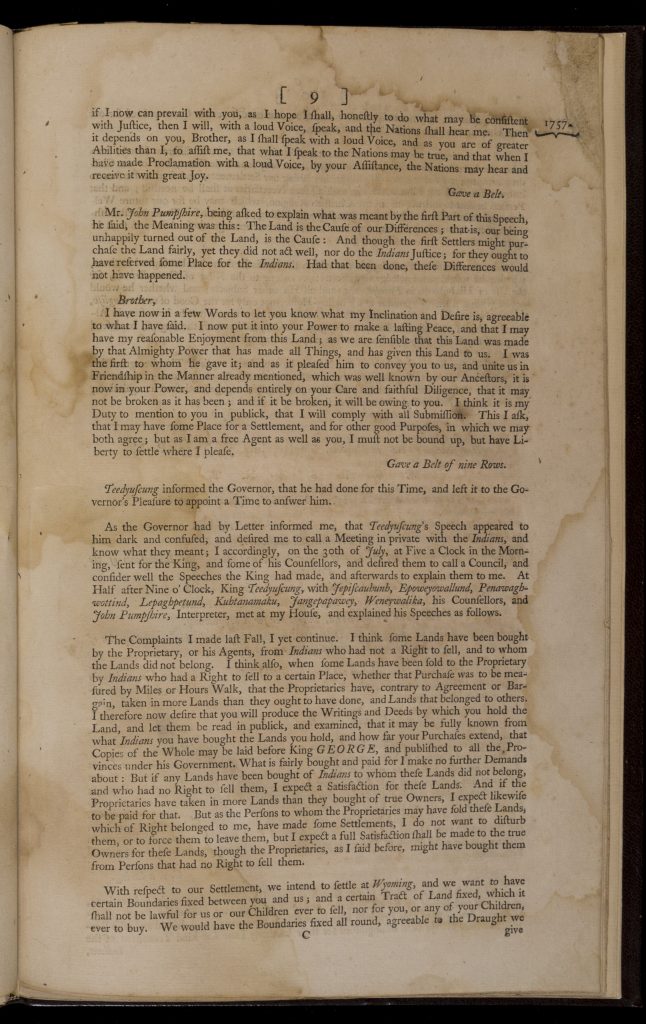

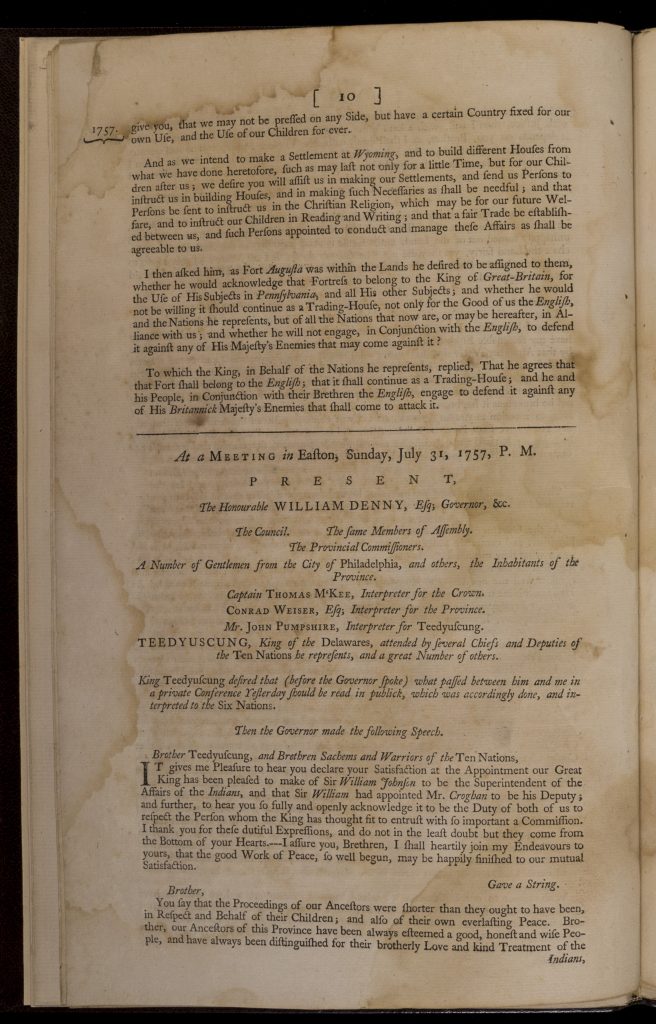

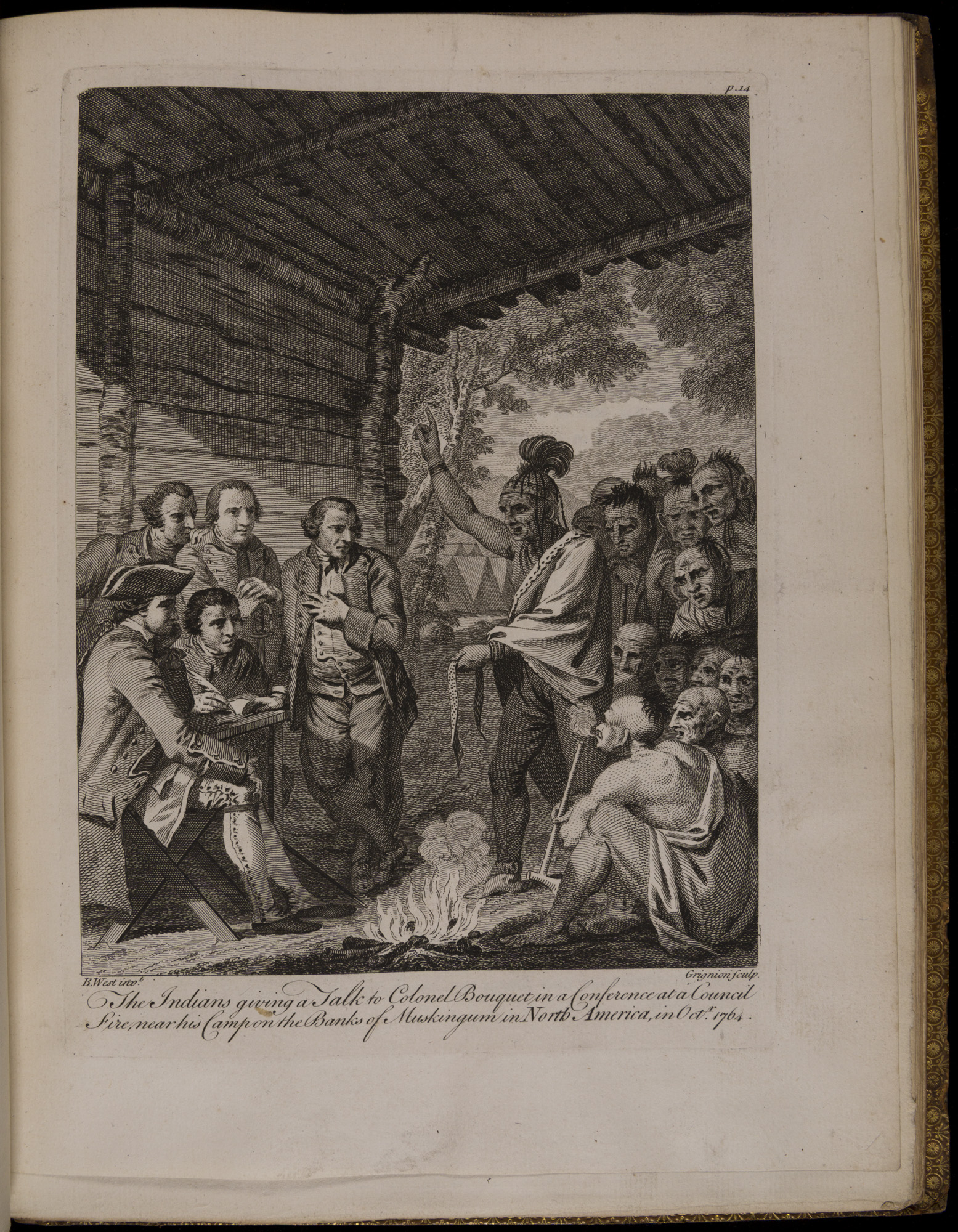

In 1758, the Lenape, led by Tamaqua and Teedyuscung, made peace with the British. At the peace conference, Teedyuscung addressed the governor, arguing that if enough land had been set aside for his people to begin with, no conflict would have occurred. He insisted that Indigenous poeple needed “a certain Country fixed for our own Use, and the Use of our Children for ever.” In addition, leaders of the Ottawa, Ojibwa, Kaskaskia, Myaamia, Potawatomi, Shawnee, and Wyandot assembled and declared a truce at Fort Pitt. The decision by Native leaders to make peace with the British was a blow to the French effort. After a series of early French victories, the British rallied and eventually, with the aid of Indigenous allies, gained possession of parts of Canada and forced the French to surrender in 1763. Terms of the peace treaty were negotiated in Paris with no Native nations represented, despite their crucial roles in the war. As a condition of the peace, Britain requested that all the captives held by hostile Native nations be released. Some Europeans refused to return and chose to remain with their adopted tribes, creating controversy and stirring up tensions.

Selection: B. Franklin and D. Hall, Printers, Minutes of conferences, held with the Indians at Easton, in the Months of July, and August, 1757 (1757).

British victory in the war contributed to a wave of new British settlement in the Ohio Valley and broader Great Lakes region. British forts did not offer security for Native people. In fact, they were outwardly hostile toward the Indigenous presence. For example, Field Marshall Jeffrey Amherst, head of the British army, made clear that the British would pursue a very different policy than the French. Under Amherst, the British discontinued most efforts to accommodate Native peoples, denying them traditional gifts and advocating tactics of intimidation.

Questions to Consider:

- What do these documents suggest about alliances between Native nations and the British during this period?

- What do the speeches at these conferences reveal about Indigenous and British strategies of negotiation? Describe the language that each respective group uses.

Pontiac’s War

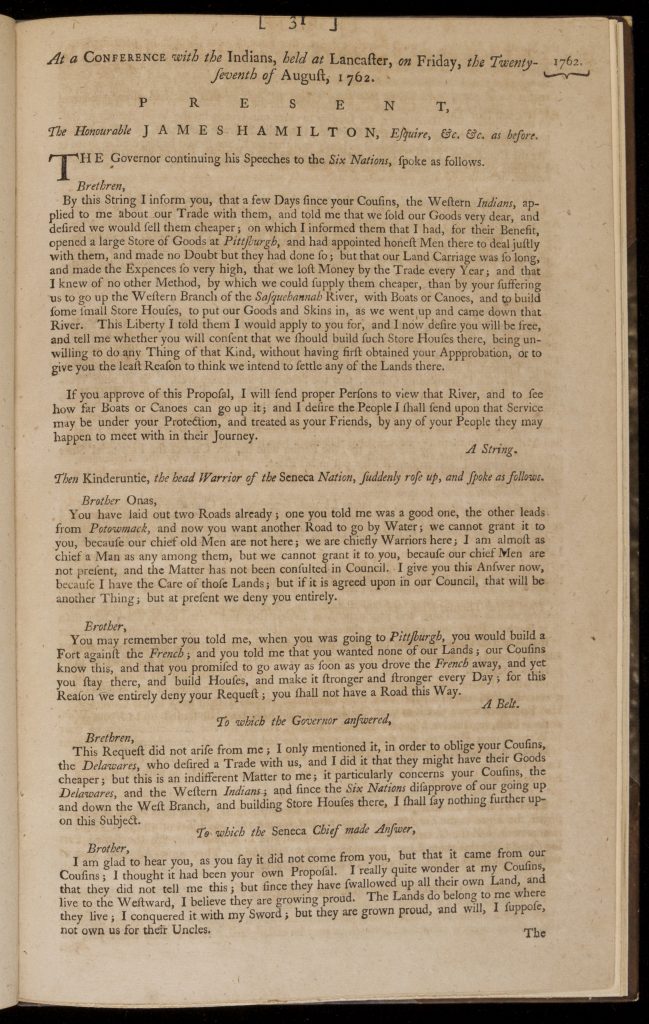

At a conference held in 1762, Kinderuntie, a Seneca warrior, rose to speak and chastised the British for not leaving Native lands after they had driven out the French. He was especially concerned that Fort Pitt remained heavily armed. He was not alone in fearing British encroachment. In 1762 Neolin, a Lenape Indian religious leader, reported receiving a message from the Master of Life calling for whites to be driven from Native land, which was made for them alone. Neolin’s theology emphasized a return to traditional lifeways and the rejection of European culture. His vision helped to mobilize a multi-nation confederation to challenge British expansion in the region. Among his followers was Pontiac, an influential Ottawa chief. Pontiac helped to forge an alliance between the Ottawa, Delaware, Ojibwa, Potawatomi and Shawnee nations to fulfill Neolin’s prophesy.

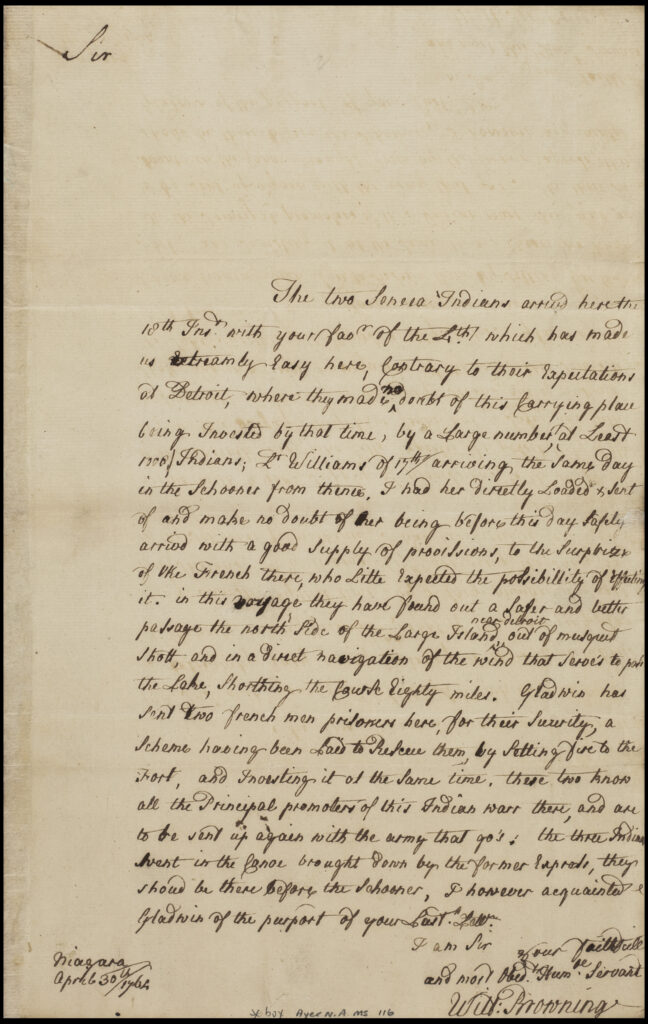

Pontiac and others sensed that fierce resistance was needed in the face of encroachments by colonial settlers and British territorial expansion. As a result, Tehy seized British forts throughout the Ohio Valley, and violent conflict broke out between various Native nations and whites. Lieutenant Colonel William Browning reported that “at least 1000 Indians” raided the fort at Detroit. This was not an isolated incident.

Selection: B. Franklin and D. Hall, Printers, Minutes of conferences, held at Lancaster, in August, 1762 with the Sachems and Warriors of several Tribes of Northern and Western Indians (1763).

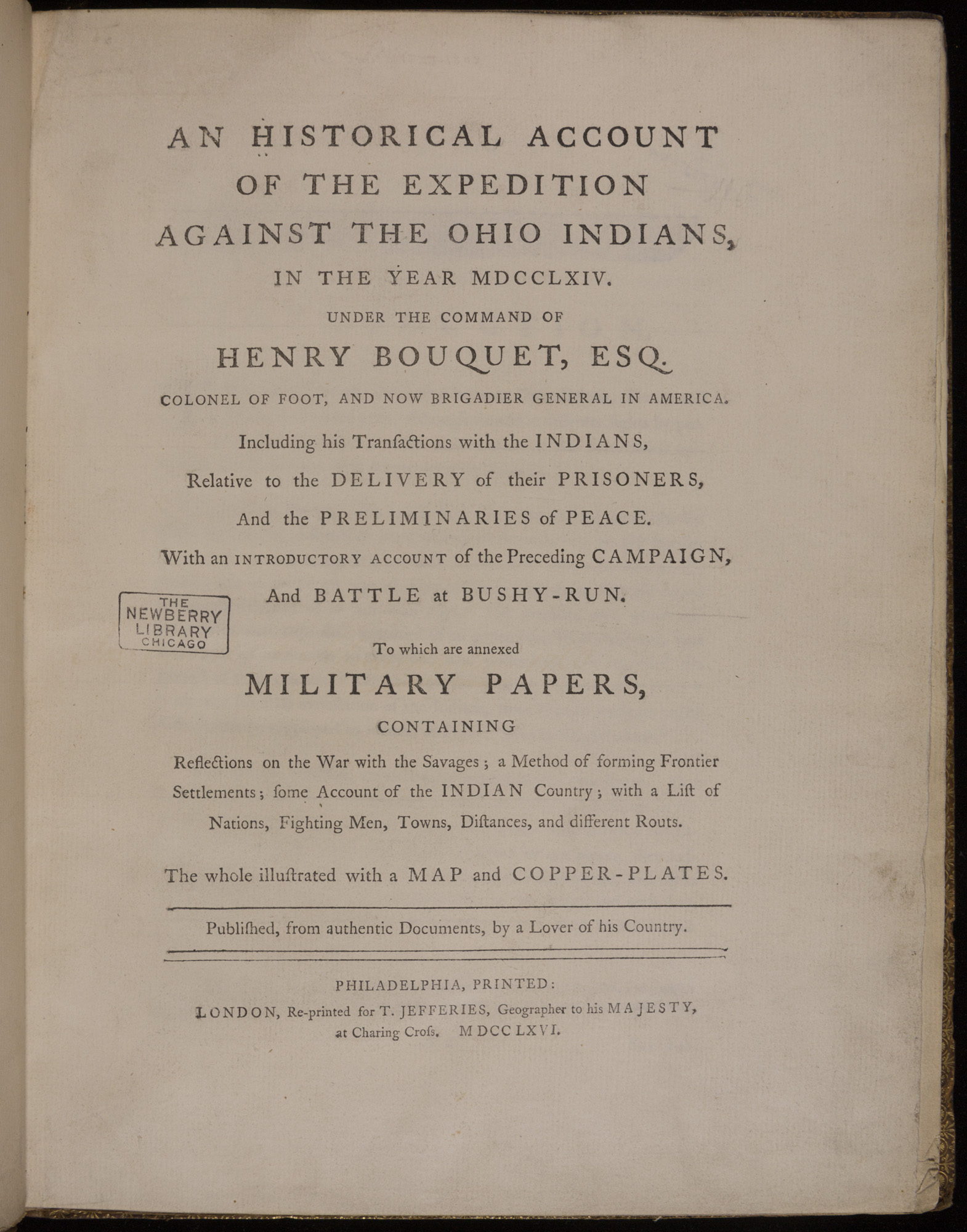

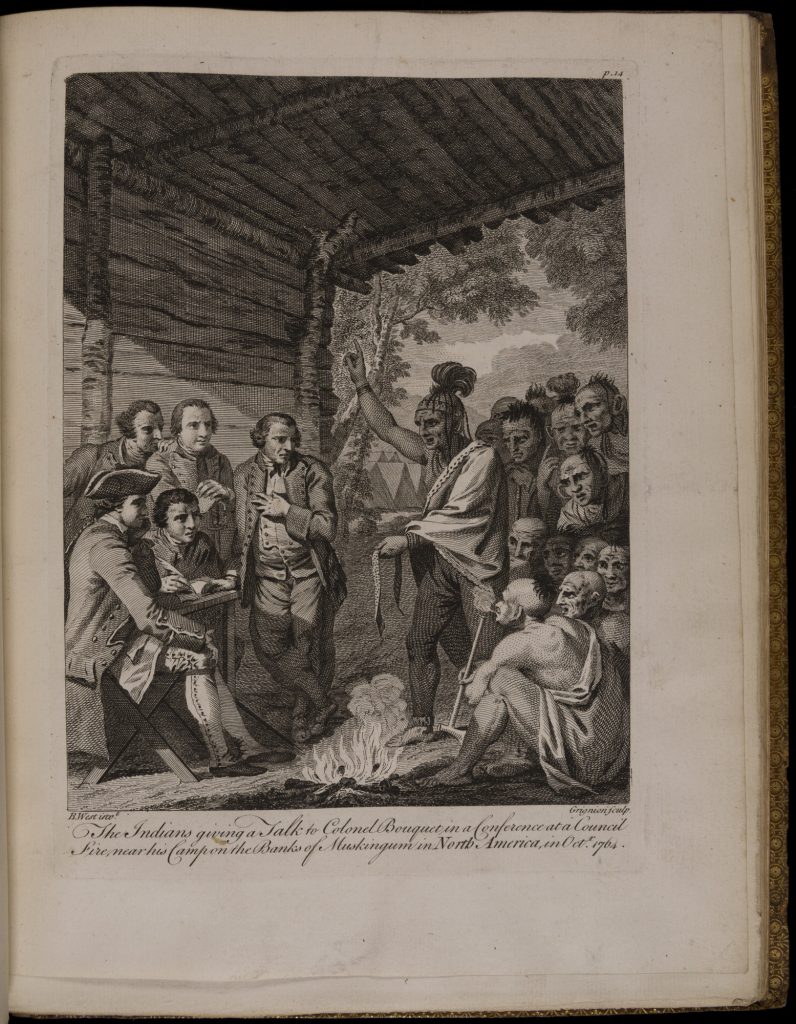

The uprising spread far and wide, provoking a diverse set of responses from the British. In an effort that remains infamous to this day, Field Marshall Jeffery Amherst wrote to Colonel Henry Bouquet approving his plan to distribute blankets infected with smallpox to Native communities and suggesting that they should also “try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race.” [Amherst to Bouquet, July 16, 1763]. In From the Heart: Voices of the American Indian, Lee Miller remarks that the “British can congratulate themselves, for they will go down in infamy as the first ‘civilized’ nation to use germ warfare.”

Selection: William Smith, An historical account of the expedition against the Ohio Indians, in the year MDCCLXIV, under the command of Henry Bouquet (1769).

In a very different approach aimed at reducing tensions, a royal proclamation issued by King George III in 1763 forbade most British settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. The Proclamation Line would separate whites from Native people in theory, but enforcement was lax. Indigenous people had reason to distrust that the line would be maintained for long. The British refused a peace offering from Pontiac in 1764 and the conflict continued through 1766. During Pontiac’s War, as it was often called, Native communities were ravaged by smallpox and suffered a series of decisive defeats after a string of early victories.

Selection: William Browning to William Johnson [i.e. Johnson] (April 30, 1764).

Racial lines hardened during the 1760s. Both Indigenous and European people increasingly referred to divisions between “red” and “white” peoples. Neolin, Pontiac, and others reflected this shift, fearing that unless Indigenous people united to challenge European conquest they would not long survive. The Paxton Boys, a group of Scots-Irish frontiersmen from Pennsylvania, fulfilled their worst fears. The armed band attacked a group of Susquehannock, murdering over twenty people, after it was rumored that they were supporters of Pontiac.

Questions to Consider:

- What does Kinderuntie’s statement in Minutes of conferences, held at Lancaster… reveal about the historical relationship between the Seneca and the British?

- How does William Browning describe the uprising in Detroit in his letter, Letter to Sir William Johnson? What motivations does he ascribe to the Indigenous fighters who were involved in raiding the fort?

- How did Jeffrey Amherst’s approach toward Native nations differ from that of the French governors in the region?

The American Revolution in Indian Country

Victory in the French and Indian War contributed to an outpouring of patriotic support for the British empire among colonists in America. Such goodwill was short-lived for some, however, as London began to tax the colonies to help reduce the war debt. The Proclamation Line of 1763 was also greeted negatively by colonists, and many feared the standing army that would be required to adequately enforce it. The following decade was marked by resistance to British attempts to tax and control the colonies, which culminated in violent revolution against the mother country. The Declaration of Independence of 1776 included grievances against the king for preventing the settlement of western lands and for having “endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare, is undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

Given the pivotal roles that Native Nations played in the events immediately preceding the Revolutionary period, it should come as no surprise that they continued to influence events leading up to the break with Britain. Despite the incendiary words in the Declaration, some Native people supported Independence. Crispus Attucks, famously one of the first to fall in the Boston Massacre, was of African and Wampanoag decent. Most often, though, the Revolution divided Native nations.

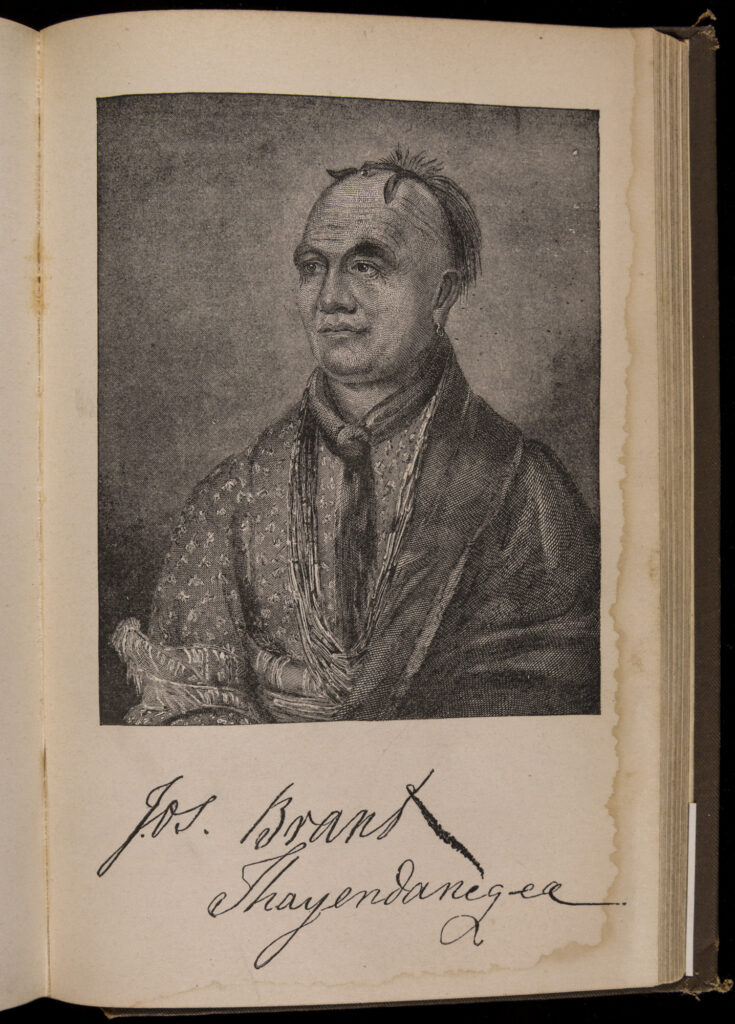

The powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy was recruited by both sides. At the 1777 Haudenosaunee council, the Mohawk chief Thayendanegea, also known as Joseph Brant, strongly advocated for going to war against the colonists. Joseph’s older sister Molly Brant, who had served as a consort for the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, was also a strong proponent of supporting the British. Their Seneca rival, Red Jacket, encouraged neutrality and viewed the conflict as a white man’s war. Nevertheless, four of the six nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy aligned with the British. Some influential leaders split with their nations and supported the rebels, such as the Oneida chief Skenandoa and the Mohawk leader Akiatonharónkwen, also known as Joseph Louis Cook. Other nations, such as the Cherokee, were similarly divided.

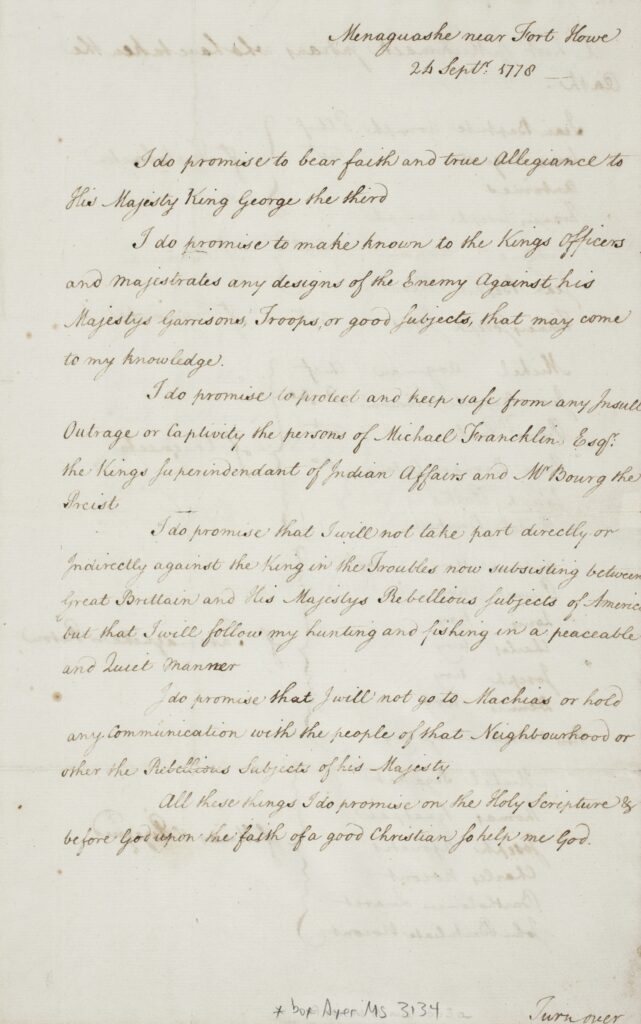

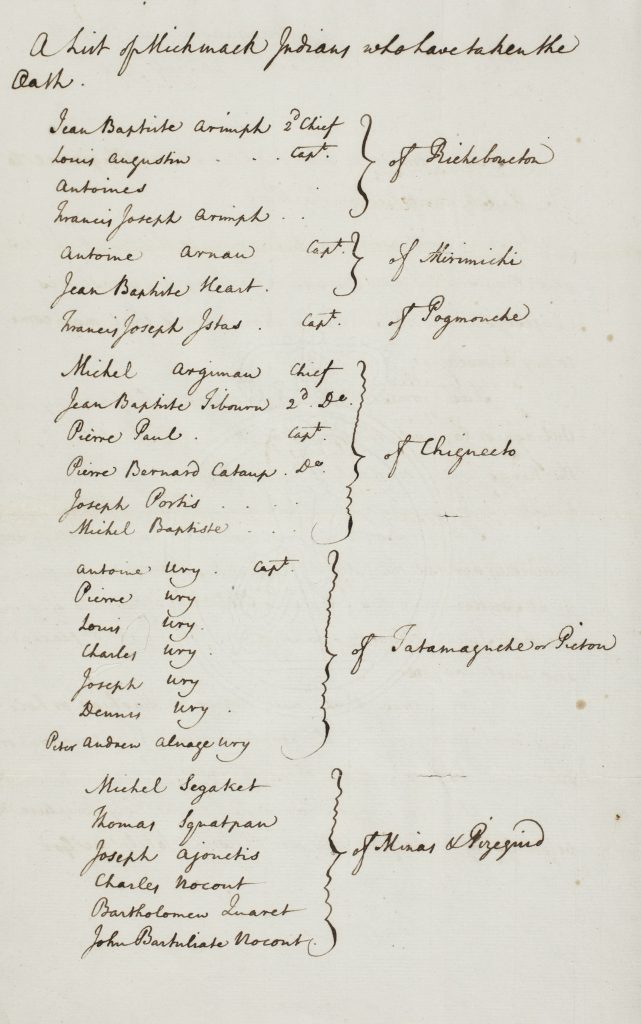

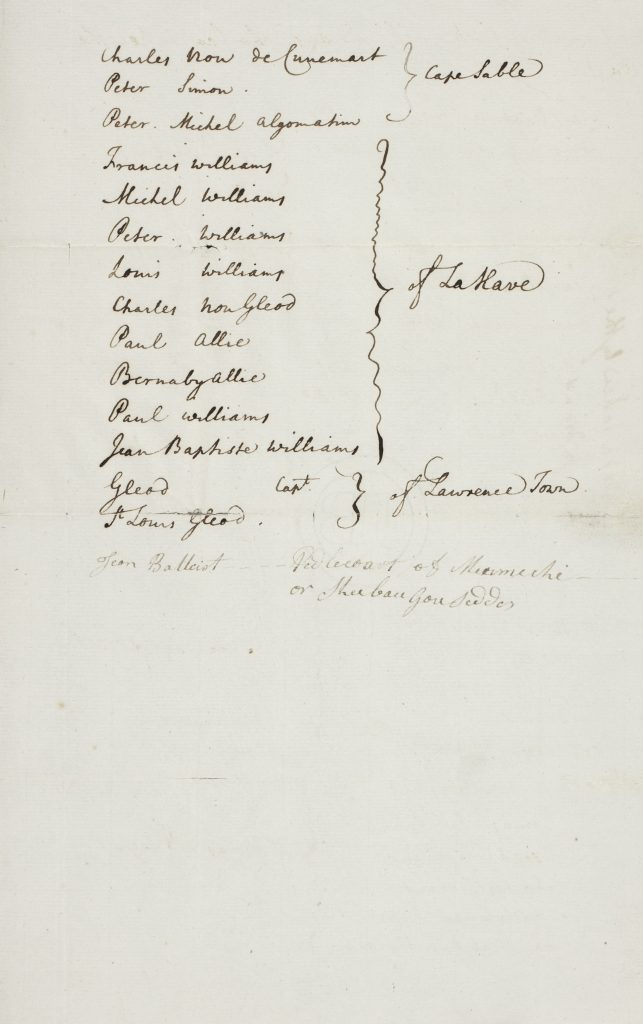

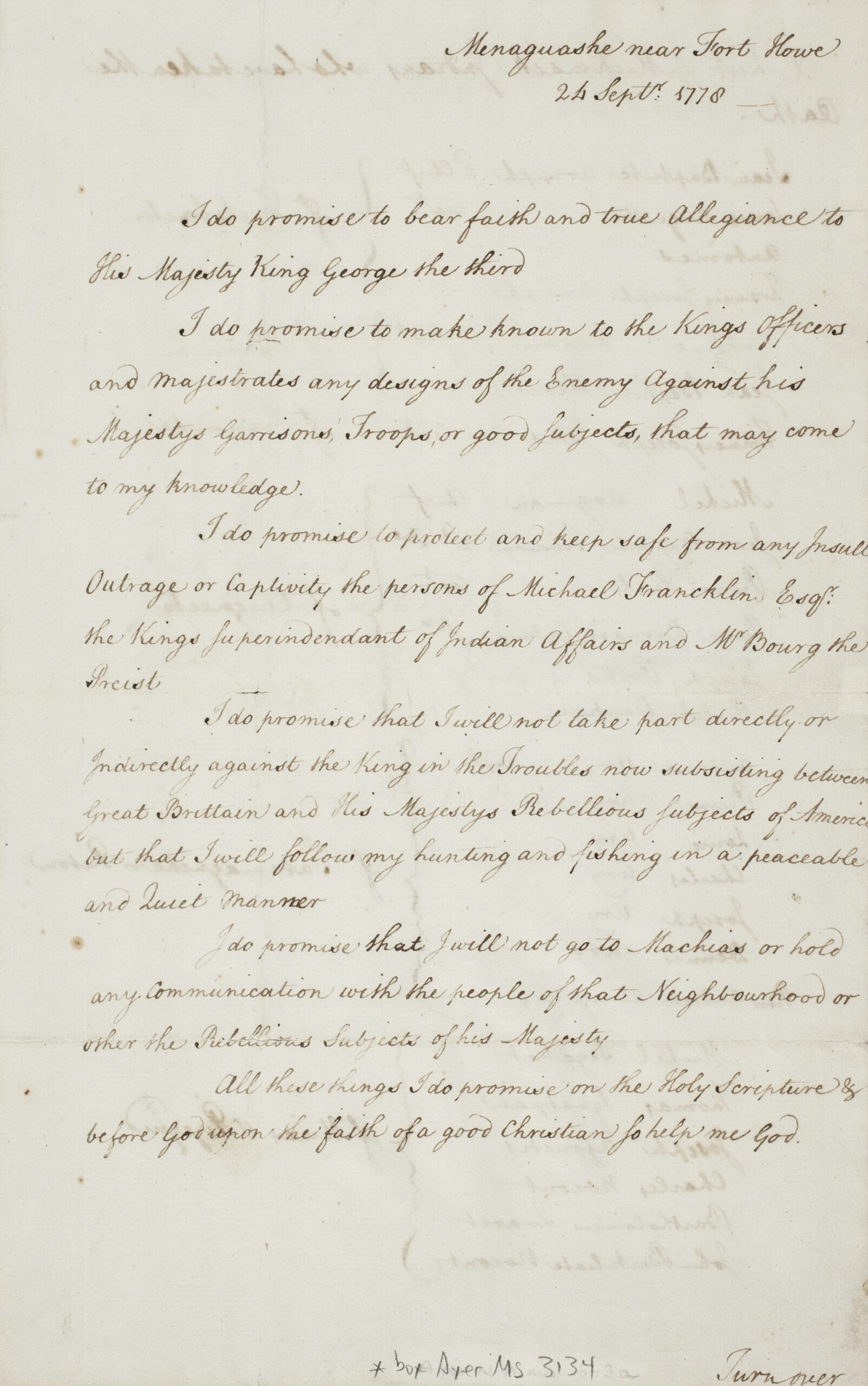

Selection: “I Do Promise to Bear Faith and True Allegiance to His Majesty King George the Third…” (1778)

The daily lives of Indigenous peoples were deeply impacted by the Revolutionary War. Tradelines were cut off, communities were torn apart, and villages often incurred damage from rampaging soldiers on both sides. The Lenape, for example, even after signing a treaty with the Americans in 1778, had two villages sacked by hundreds of rebel soldiers in 1781. A year later, British troops captured a group of Lenape accused of aiding the Americans and held them at a prisoner of war camp in Ohio. As historian Colin Calloway observes in The American Revolution in Indian Country, for many Indigenous people “it seemed the American Revolution was truly a no-win situation.” Even those nations that supported the American rebels gained little as a result. In the aftermath of the war, the balance of power shifted dramatically, leaving Native nations in a new geopolitical climate where they could no longer effectively play one imperial power off of another. Indigenous peoples developed new strategies as the United States of America solidified its status as a new nation.

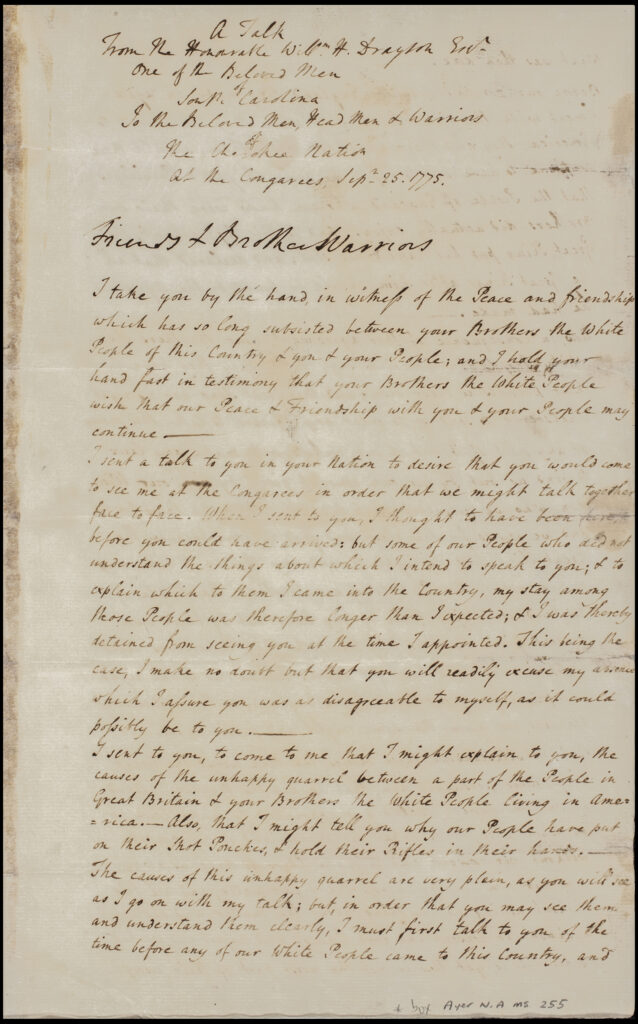

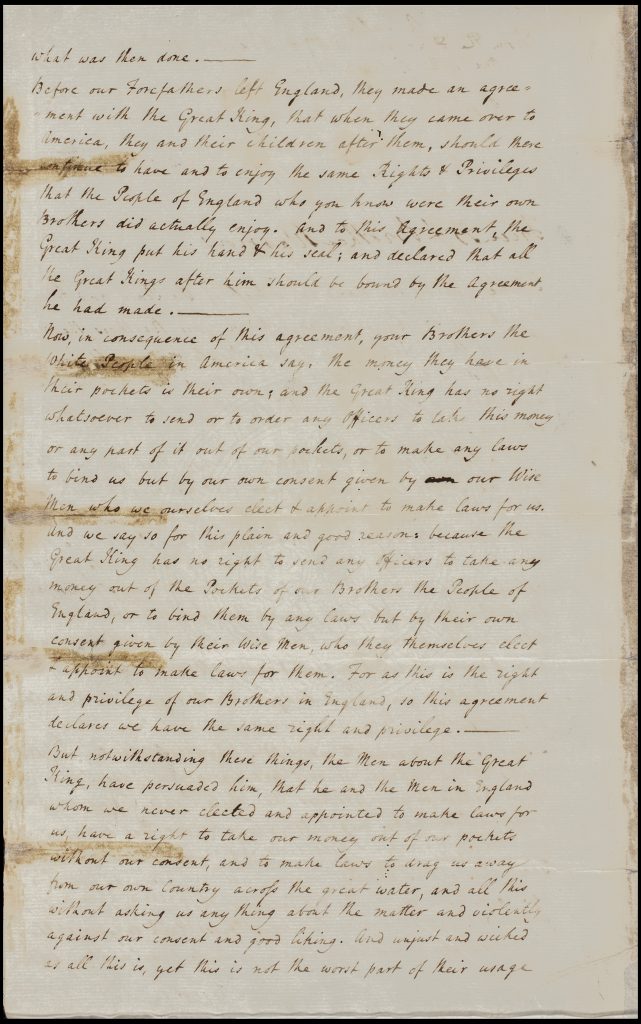

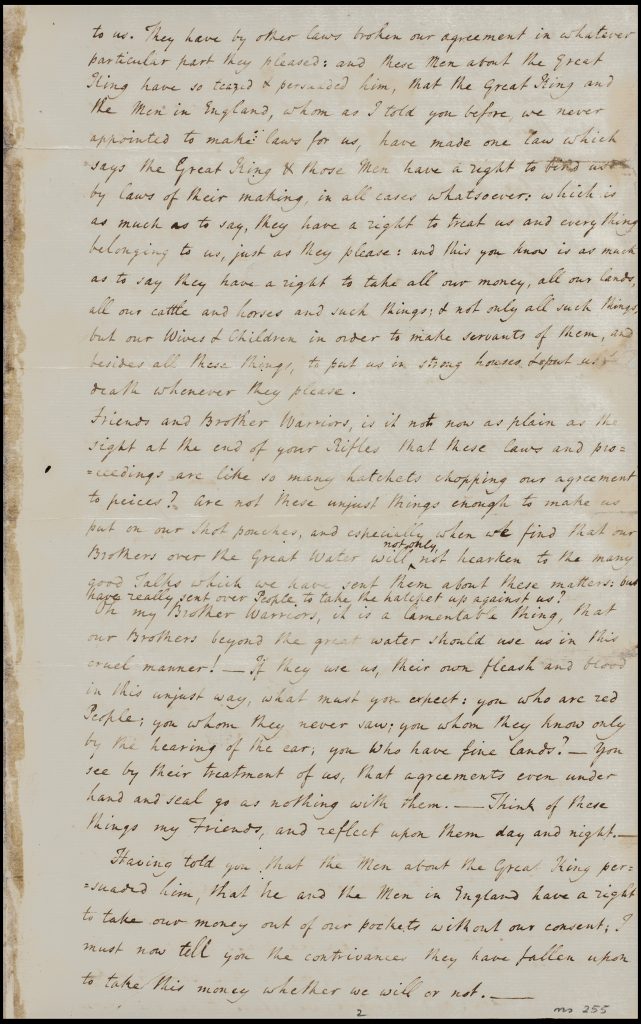

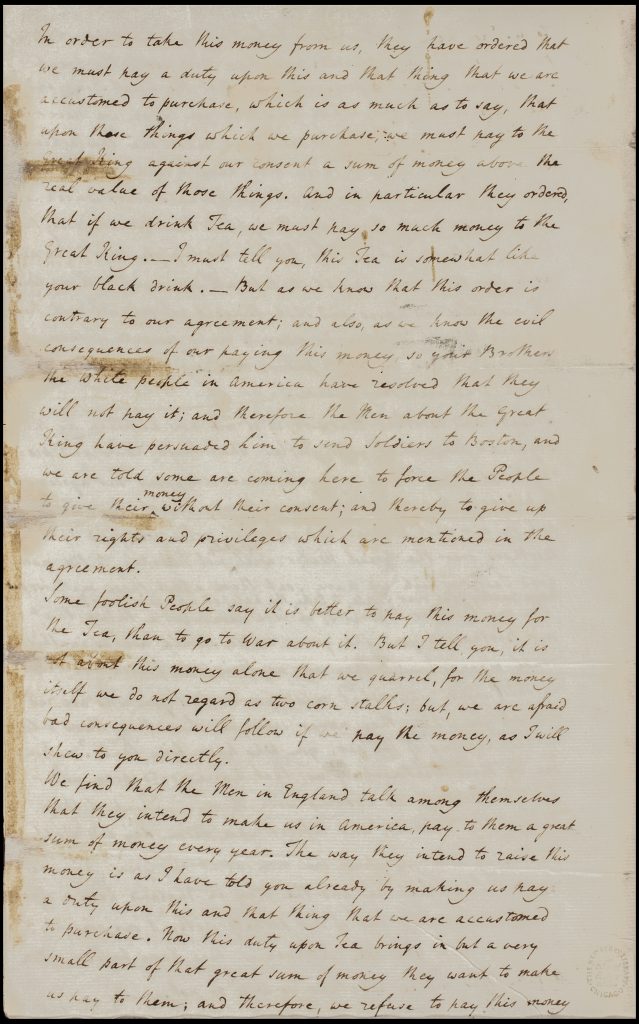

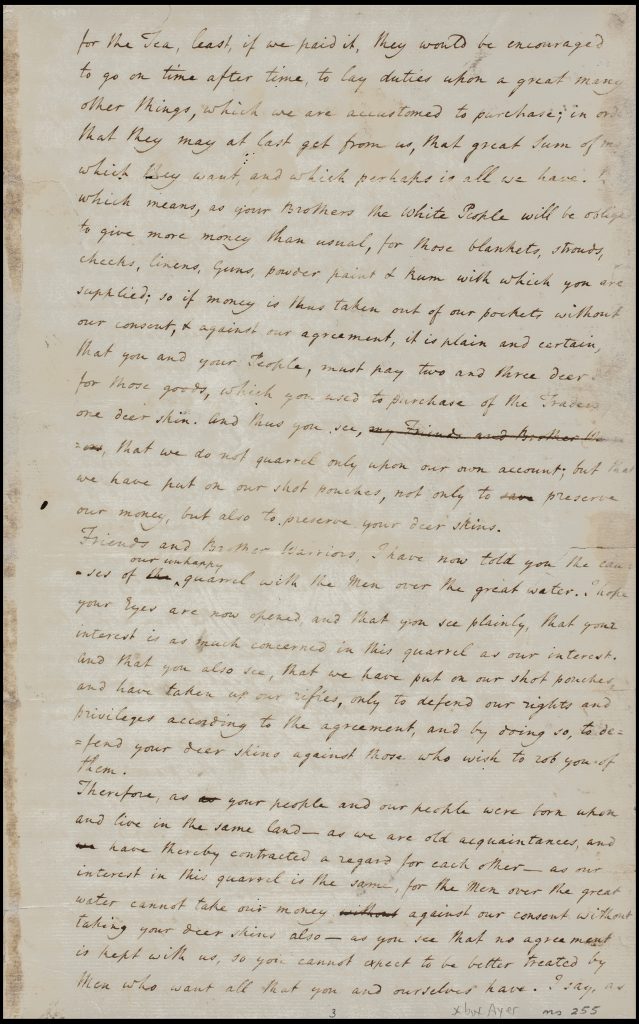

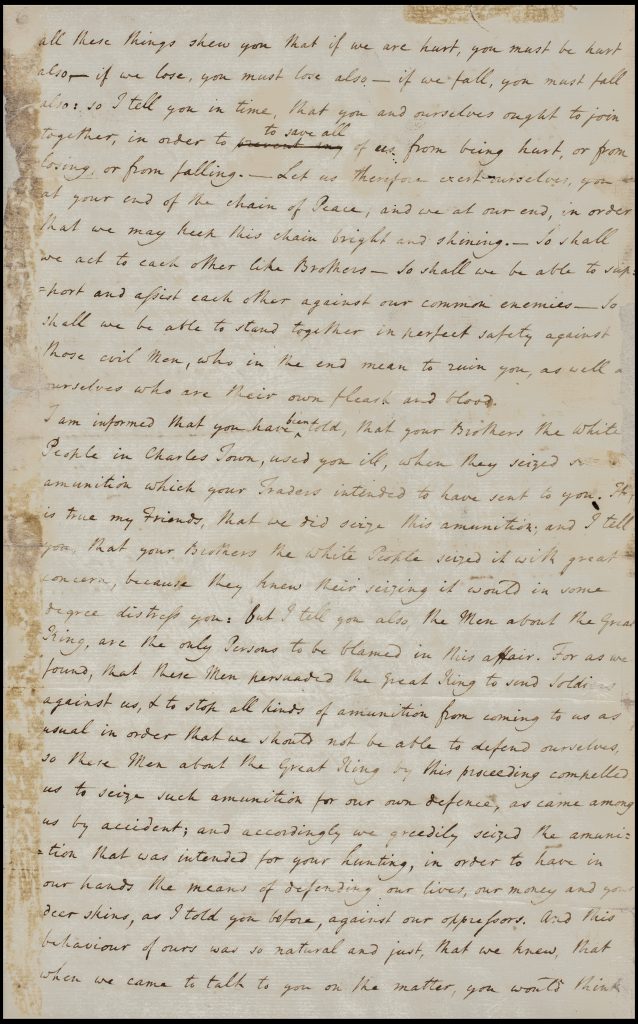

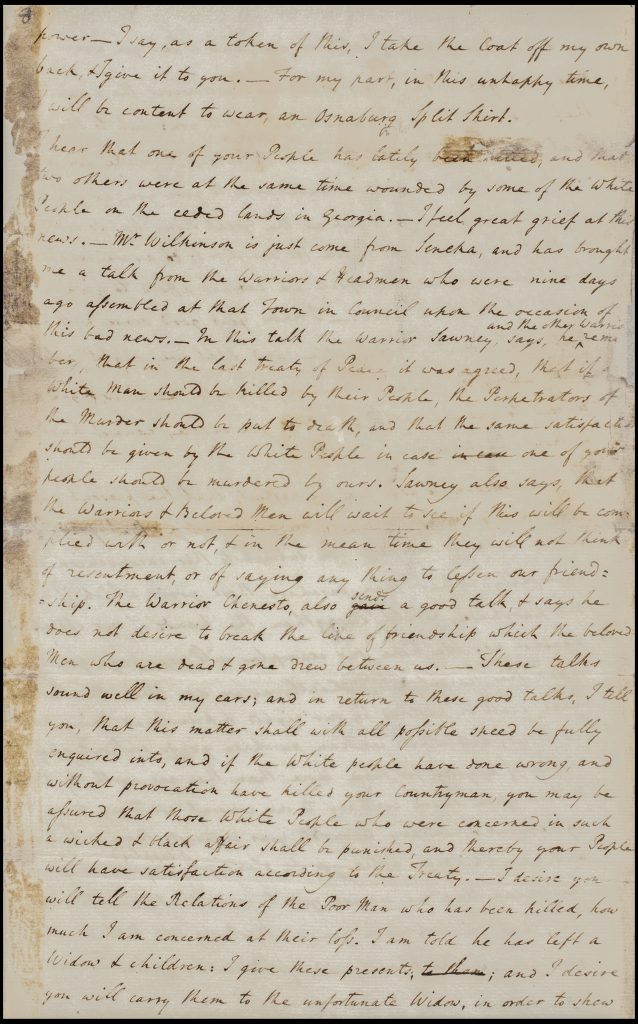

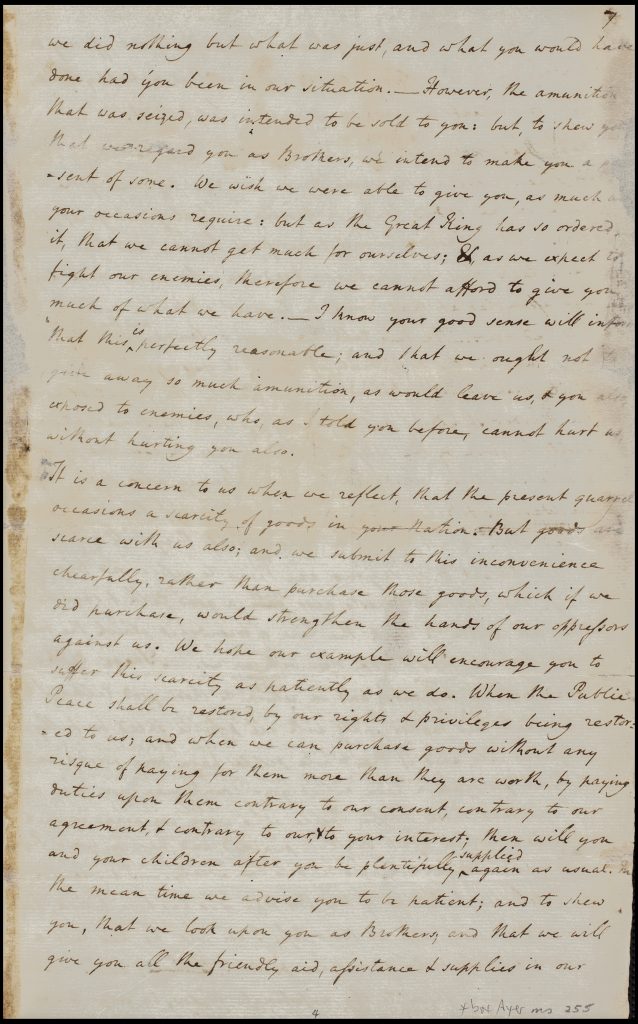

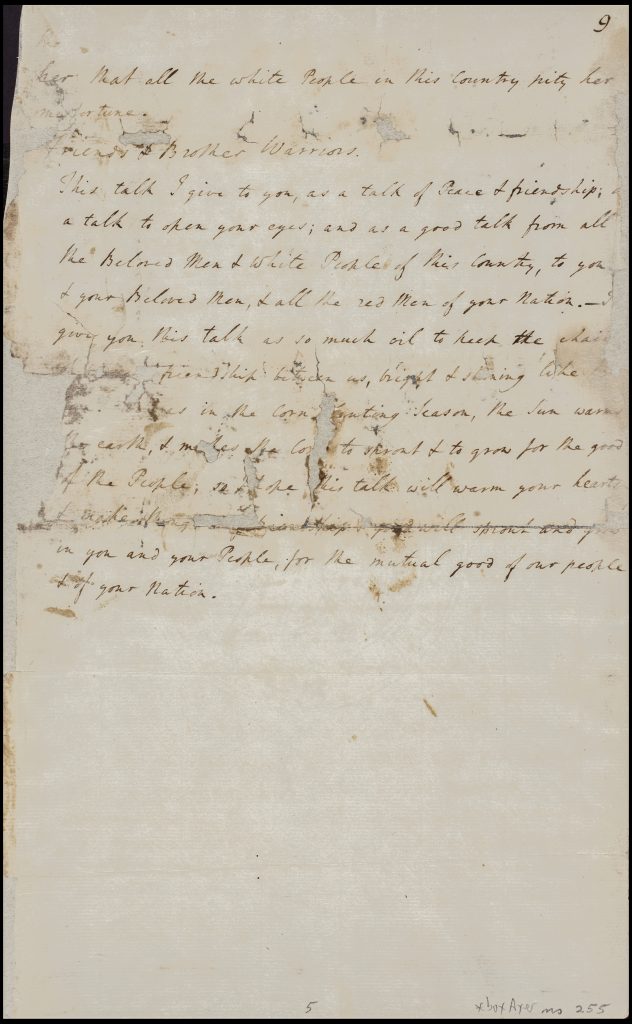

Selection: William Henry Drayton, “A talk from the Honorable Will[ia]m H. Drayton Esqr., one of the beloved men of South Carolina: to the beloved men, head men & warriors of the Cherokee Nation at the Congarees (September 25, 1775).

Questions to Consider:

- What arguments does William Drayton employ to convince to the Cherokee to join the cause?

Indigenous perspectives in the late 1700s: texts

This digital collection seeks to view the political and social events of late 1700s America from the perspective of indigenous peoples. Below you can find several documents which are useful in examining this viewpoint and considering the ways in which Native leaders experienced and shaped history in the late 1700s.

Indigenous perspectives in the late 1700s: maps & images

Below you can see maps and images depicting Indigenous and European colonizer relations in the late 1700s.

Further Reading

Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Axtell, James. “Colonial America without the Indians: Counterfactual Reflections,” Journal of American History 73 (1987), pp. 981-96.

Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. 1995.

Dowd, Gregory Evans. A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745-1815. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Dowd, Gregory Evans. War Under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, & the British Empire. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Fisher, Linford D. The Indian Great Awakening: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Holton, Woody. Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves, and the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Middleton, Richard. Pontiac’s War: Its Causes, Course and Consequences. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2012.

Miller, Lee. From the Heart: Voices of the American Indian. New York: Knopf, 1995.

Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. New York: Viking, 2005.

Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions : A Continental History, 1750-1804. First edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Taylor, Alan. The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Related Newberry Resources

A custom curriculum hosted by the Newberry and centered on Chicago as a Native Place.

Created in alignment with Illinois State Standards and to support the HB1633 mandate to teach Native history.