Curriculum Connection: African American History, Great Migration, Labor Movement, Progressive Era

This is a guided lesson incorporating three different sources. The first and second are primary sources: an advertisement for the Pullman Company and an employee card for a Pullman porter from the Pullman Collection. The third is a secondary source: an encyclopedia entry about the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters from the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

This lesson is for a teacher-controlled class. If you would like your students to work with the source independently or in small groups, there are links above for the sources alone as well as a student worksheet.

With more advanced students, present the sources without any background. Allow students to discover everything they can from them and, possibly, their own research. If desired, follow the script throughout the lesson and share the background material provided at the end of the lesson.

Process

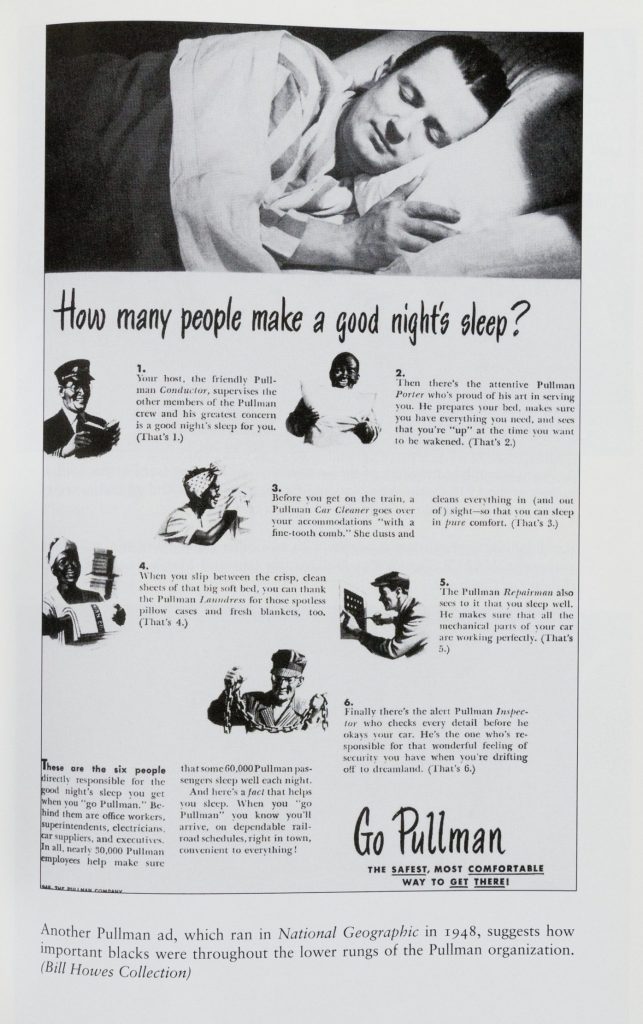

Source 1 – Primary Source – Advertisement

Display the first source. Initially display it without a caption and engage students in an exploration of the source without providing any information to prompt students’ curiosity and develop their inquiry skills. Zoom in on different sections to help students focus.

Ask students a variety of questions to lead them through the advertisement and generate their own inquiry and discussion.

- What is this? (An advertisement)

- Is this a primary source?

Explain that while this is not an eyewitness account of something, it is still a primary source because it’s an artifact from a particular time period that can serve as an original source of information about opinions and attitudes from the time period concerning the topic.

Give students time to look at and read the source. Then have them write down everything they can about it. Accept a variety of answers and details.

- What or who is this source about? What does it show?

- Do you have an idea about when this was created? How do you know?

If necessary, lead students and point out the subject matter of the ad—the benefits of a Pullman sleeping car.

- Do people often travel by train today? Do they often sleep in a sleeping car?

- Have you ever heard of a Pullman sleeper?

- How could you find more information about when the ad was created?

Have students consider the purpose of and audience for the object.

- What was the purpose of this item and who was it created for? (The purpose was to sell people on traveling in a Pullman sleeper, made for train travelers—typically more well-off travelers.)

Only after students have examined the image by itself, with no additional information, provide students with the caption.

- What does the caption tell you about the source? (The caption tells when and where the advertisement was published—National Geographic, 1948—and what source book the image was found in.)

- Does this change what you think about the source? (Answers will vary. Students might note that knowing when the image was first published helps them understand it better. Others might note that finding out that the image was used in a book about Pullman porters makes them pay more attention to the section of the ad about the Pullman porter. Some might argue that the caption does not change their perception at all.)

Discuss with the class whether their initial perceptions about the source were correct. You may want to review the Skills Lesson: Reading a Caption.

If students haven’t introduced the subject themselves, explore the way the figures in the ad are depicted, including how gender and race are portrayed.

- Does anything in this image show bias. (Bias is a tricky subject. Accept a variety of answers but ask that students provide evidence from within the source to support their conclusions. Some students might point out that no women are depicted in a role other than as a cleaner or laundress and the African Americans depicted are all in domestic positions and argue that this show bias. Other students might argue that none of the depictions is insulting or less respectful than the others and that this shows the ad isn’t biased, although the hiring practices of the Pullman Company might have been.)

Introduce students to the idea that everyone brings their own experiences, background knowledge, and biases to how they interpret a source.

Ask a series of questions to help students identify what they bring to their examination of the source:

- What do you know about life in the United States in the late 1940s and the 1950s?

What do you know about racial laws in this time period? - Have you ever heard of Pullman porters? Have you ever heard of Pullman maids?

Finally, help students use this source to begin thinking like a historian and to begin a larger inquiry.

- What is at least one question the source makes you think of? (Have students note their question or write students’ questions for all to see.)

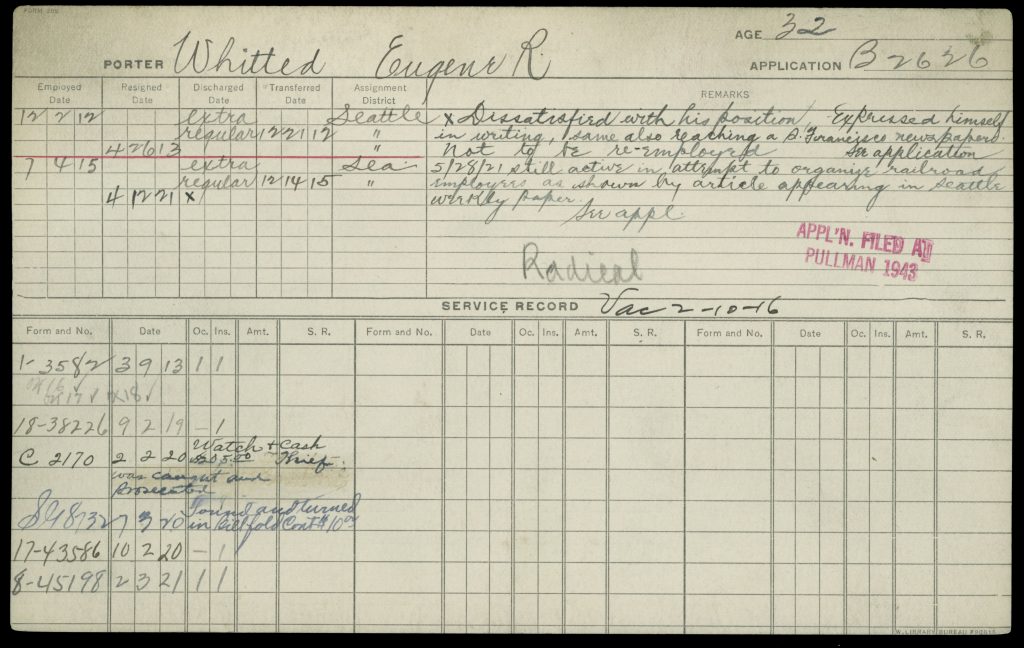

Source 2 – Primary Source – Business Record

Display the second source. Again, initially display the source without a caption. Explain that historians don’t rely on just one source, but examine a variety of sources.

Hand out or display the image. Give students time to examine its details and write down their conclusions about what they are looking at.

It is possible that students will require some time to examine, make inferences, and come to conclusions about the source.

- What is this object?

- Who is it about?

- What information does it give you about that person?

- What do the words Porter, Age, and Service Record tell you?

If necessary, lead students through the document. Point out these words on the form: Porter, Age, and Service Record. Explain that this is an employee card. Help students understand that this card is for Eugene Whitted, whose earliest Employed Date was in 1912 when he was age 32. His Assignment District (fifth column from the left, upper part of the card) was Seattle.

Help students decipher the text under “Remarks” on the right side of the card.

The transcription of these remarks is:

xDissatisfied with his position Expressed himself in writing, same also reaching a S. Francisco newspaper

Not to be re-employed See application

5/28/21 still active in attempt to organize railroad employees as shown by article appearing in Seattle weekly paper.See appl.

Radical

- What does “organize railroad employees mean”?

- What does “Radical” mean?

Students might not know the answer to these questions. If not, consider using this as an opportunity for them to do their own research. Have students see if their questions can be answered by another source in the lesson or through their own research.

Depending upon the sophistication of your students, you might want to have them read the information at the bottom of the card: A notation in February 1920 records that Whitted is accused of stealing a watch and cash [$205.00]. The card says he was caught and prosecuted. In July 1920, he was still working for the company and found and turned in a billfold [wallet] containing $10.00.

Now that students have examined the source, provide students with the caption.

- What is this item?

- What was its purpose and who was it created for? (It is an employee card with the employee’s history for the managers of the company.)

- Does the caption give you new information about the source?

- Is that information important in order to understand the source?

- Is it helpful in other ways?

If students have deciphered the source during the close examination, they might conclude that the caption doesn’t give them any new information, but they should be aware or be made aware that the caption does provide information on where the source came from (the Newberry Library) and why that is important (They know where to find the original of the card or where to find more employee cards.)

Help students explore possible bias in the source.

- What does this card show about the company’s attitude toward unions? (Help students link the fact that the card says “not to be re-employed” to his activities and how or whether this shows bias.)

Then have students consider how the first and second source relate to each other.

- How does this source relate to the first source? (This source connects to the Pullman porters in the previous source.)

Finally use the source to generate more questions

- Does this source answer any of your questions?

- Does it raise new ones? What are they?

- Where could you look to get answers to your questions?(Responses will vary. If students focused on the Pullman porter in the earlier source, then this might partially answer a question about what their jobs and lives were like. Questions raised by this source could ask what happened to Eugene Whitted, what his life was like, what the words “organizing” and “radical” mean, among others.)

Source 3 – Secondary Source – Encyclopedia Entry

After the class has examined the second source, have them read the third source, an encyclopedia entry on the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

The International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids was the first African American labor union chartered by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Pullman porters, dissatisfied with their treatment by the Chicago-based Pullman Company, sought the assistance of A. Philip Randolph and others in organizing their own union, founded in New York in 1925. The new union assigned Milton P. Webster to direct its organizing in Chicago, home to the largest number of Pullman’s 15,000 porters.

For African Americans, porter and maid jobs, when supplemented with tips, paid better than many other opportunities open to them, yet less than those jobs on Pullman cars denied to them by their race. Porter and maid jobs also retained African Americans in servile relations to white passengers. Moreover, segregation persisted even in the North, where blacks were limited in where they could spend their stopovers while on the job.

In addition to the often overlooked maids who organized for the union, the wives of porters also assumed an important role in the decade-long struggle for union recognition. Their auxiliary functions and support were significant contributions to the union’s efforts. More than half of Chicago’s “Inside Committee” were women.

As a black organization, not just a union, the Brotherhood was an important early component of the civil rights movement. Porters distributed the Chicago Defender after that black newspaper was banned from mail distribution in many southern states. The Pullman Company’s recognition of the union in 1937 and the expansion of Brotherhood membership and activities slowly fractured segregation within the AFL.

In 1978, the decline of the railroad industry led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to merge with the much larger Brotherhood of Railway, Airline, Steamship Clerks, Freight Handlers, Express, and Station Employees.

- What was the purpose of this text and who was it created for? (Secondary source to explain the basic history of the union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids. The source has been created for the general public.)

- What is the main idea of this text? (The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was an important union for African Americans.)

- How does this source relate to the other sources presented here? (The source is about Pullman porters and shows that they successfully unionized. All the other sources show Pullman porters at work or as workers.)

- Does this source answer any of your questions?

- Does it raise new ones? What are they? (Responses will vary. For some students, the source might explain the importance of Pullman porters in the African American community. It might answer questions about “organizing” and “radical” in the second source. New questions for students might include the role of women in the union and the workforce, or how the union influenced the civil right movement.)

Background

George Pullman began making luxury railroad cars in the 1850s. By the late 1860s he had founded the Pullman Palace Car Company, which—as the name implies—produced luxury dining, lounge and sleeping cars. By the late 19th century the name was changed to the Pullman Company.

Pullman hired African Americans to work as porters, maids, and laundresses. Generally, the railroad trades barred African Americans from working as engineers or maintenance workers. They also couldn’t serve as conductors. However, Pullman was credited by many in the community for hiring African Americans in large numbers and for paying a decent wage. According to the Pullman Museum, by 1920 Pullman was the second largest employer of African Americans in the United States.

Pullman porters were among the elite of the African American urban middle class with jobs that provided stability and prestige. They were a group of workers emblematic of the Great Migration. At the same time, a porter’s work could be incredibly difficult. Much of their income came from tips, and they were not paid for setting and cleaning up duties. They had to pay for their own food, lodging, and uniforms as well as reimburse the company for any items stolen by passengers. They regularly faced discrimination from customers and were often called “George” after the company founder, rather than their own names.

Extension Activities

Ask students to think about all the sources in this lesson and the picture they painted. Discuss with students what element of the lesson most captured their interest. Were all their questions answered? Where could they find information for their unanswered questions? What new information would they like to discover? Where could they look to find that information?

(Responses will vary. Students might want to explore the working conditions for the porters and maids, learn more about the union or the influence of porters in the community. They might want to pursue why the Chicago Defender was banned or the effect of its distribution on people in the South. Students should identify that they can look on the internet, in online databases at the local public library, in the books mentioned in the captions, and elsewhere for more information.)

- Have students research other employee cards from the Pullman Collection at the Newberry and report back to the class on the work lives of the people they found.

- Have students find oral histories of Pullman porters and write a short essay on how the oral histories added to their understanding.

- Contact the Newberry to see if Eugene Whitted’s application is part of the collection and see if they can obtain a copy.

- Do online research (including via the U.S. census) to find out more about Eugene Whitted’s life before, during, and after he was employed as a porter.

Additional Resources

“The Pullman Porter,” in “Labor and Race Relations” on the Pullman Museum site

“The Pullman Story, Part 2” on the National Park Service site

Available from the Newberry Library – Not Digitized

Employee indexes and registers, 1875–1946. Pullman Company. Personnel Administration Dept.; Pullman’s Palace Car Company. 1875–1946.

The Pullman porters’ review. Pullman Porters’ Benefit Association of America. Pullman Porters’ Publishing Company. 1913–1921

Pullman news indexes and article transcripts, 1922–1947. Pullman Company, creator.; Midwest Manuscript Collection (Newberry Library); Newberry Library. 1922–1947

Words to Know

transcription │ the typed text of a handwritten document or an audio recording

bias | preference or perspective, especially one that leads to prejudice

Download copies of the Pullman Porters lesson plans and sources below.