Written by the Newberry Library’s Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts Suzanne Karr Schmidt as a companion to the 2023 exhibition Pop-Up Books through the Ages. Many of the books in the show can be seen in motion here.

Introduction

Books with interactive flaps, dials, pop-ups, and other moving parts have captivated readers of all ages for centuries, even before the beginning of printing. Today we might think of movable books as being primarily pop-ups, intended for children. Yet, pop-ups are just one example of an extensive history of movable books.

The Newberry’s collection includes hundreds of books, maps, and printed sheets of ephemera (items intended for short-term use) with hands-on components. Dating from the late-1400s to the present, the moving parts within these publications enabled a wide range of users—from mathematicians to emperors to children—to better grasp the workings of their world.

The art, science, and business of creating and printing movable books developed gradually over centuries, and different readers interacted with these tactile objects in multiple ways. Scholars constituted the initial audience and could construct movable elements in early books themselves. The format soon inspired general education, and informed modern artist books, eventually becoming more theatrical and complicated.

Paper in Three Dimensions: The Parts of Movable Books

The main interactive components and structures of movable books include:

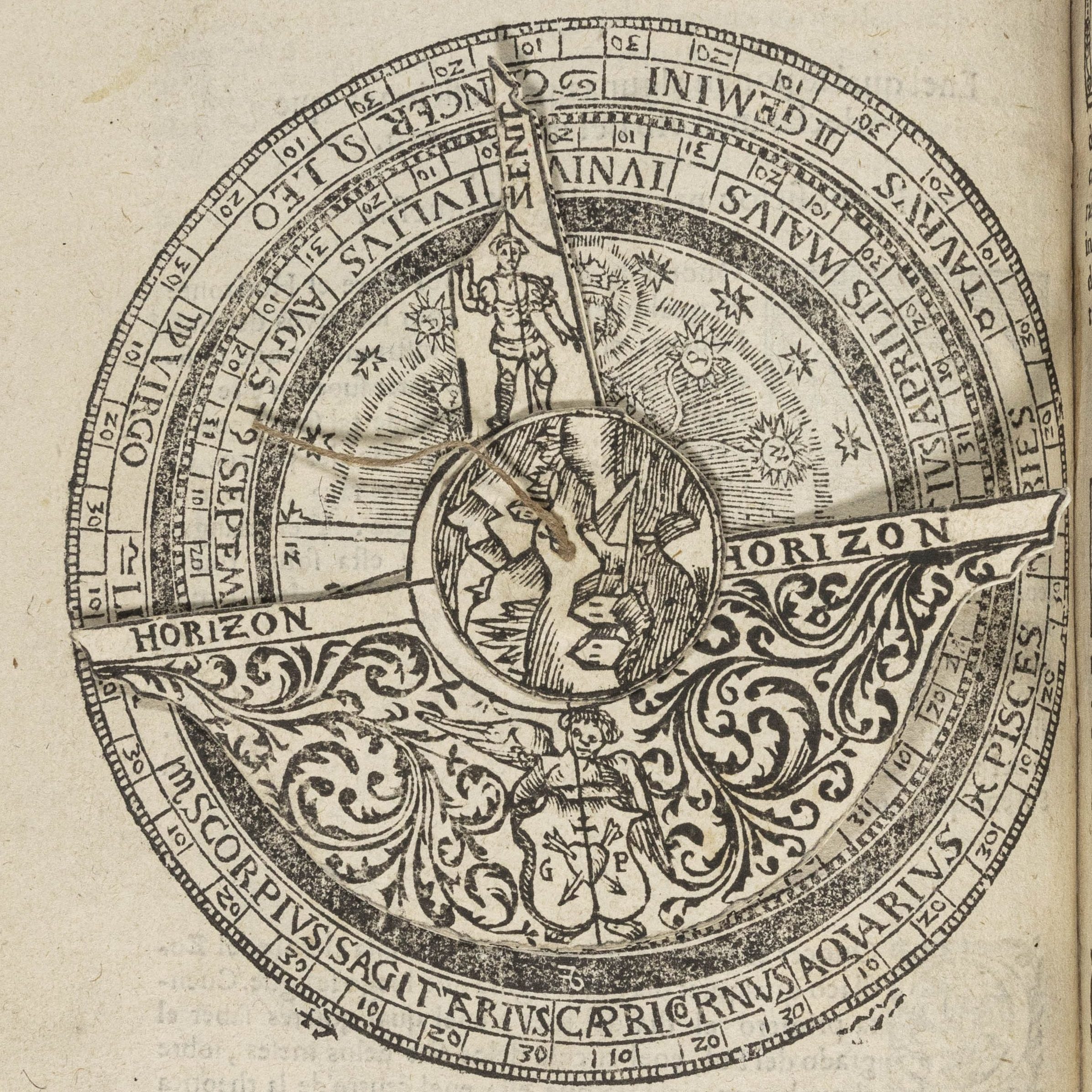

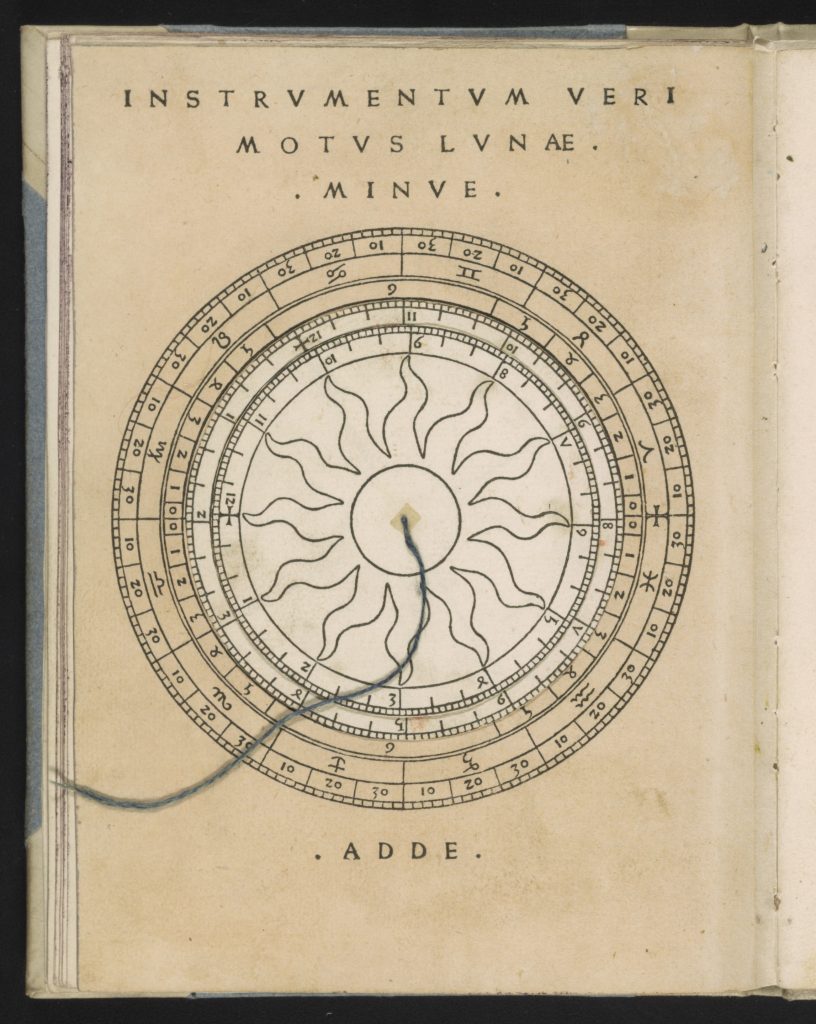

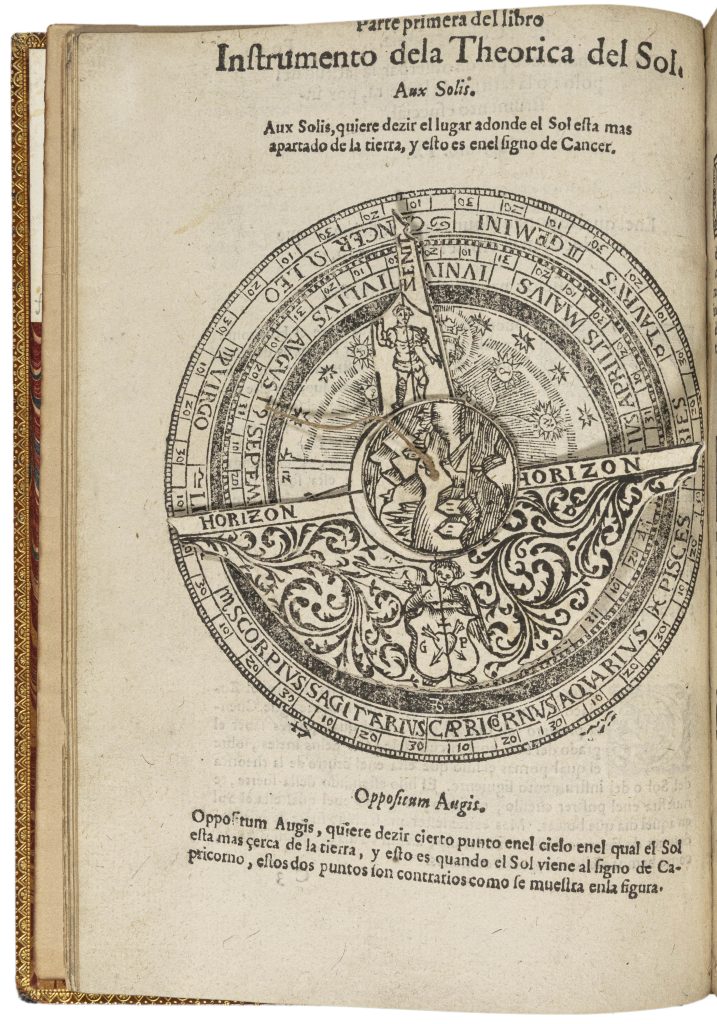

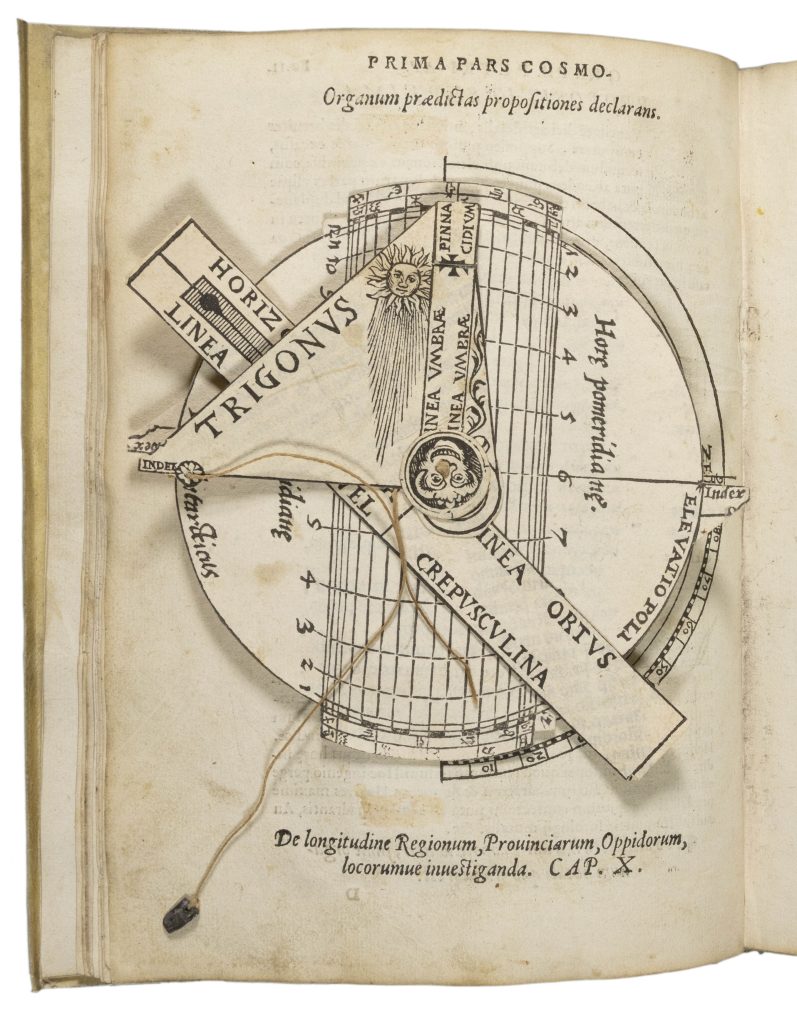

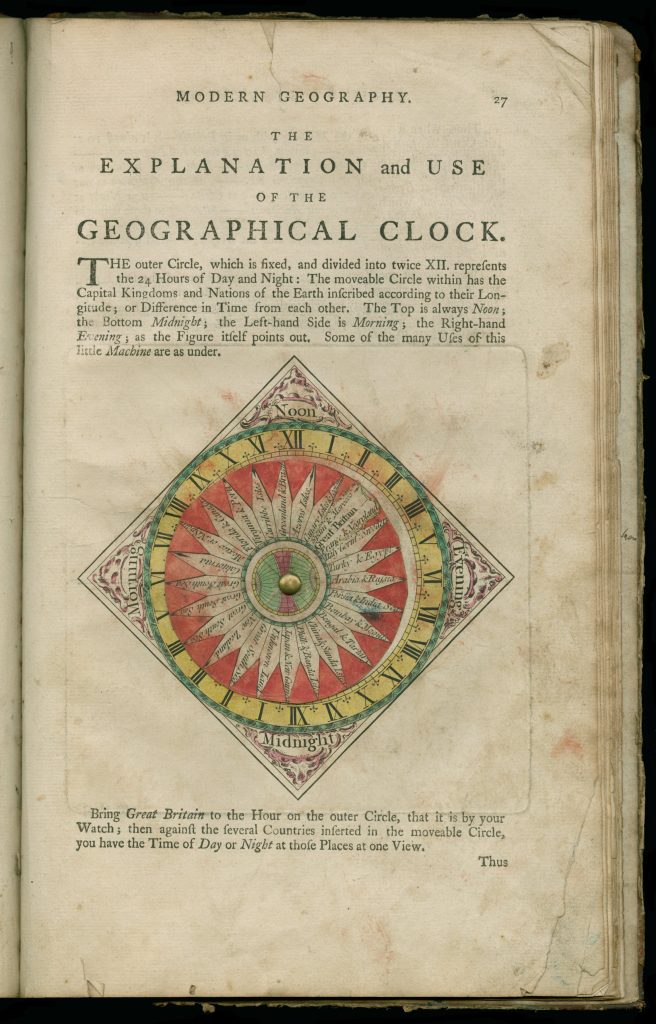

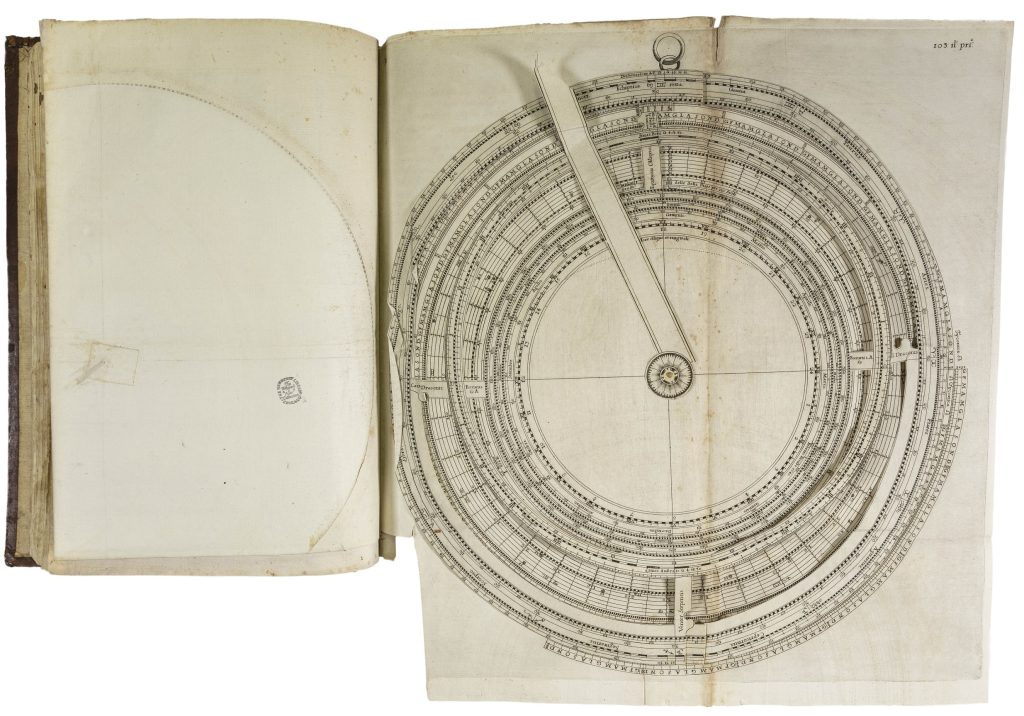

volvelles—Rotatable (but not always round) dials used to perform calculations or create optical illusions.

flaps—Paper extensions that can be lifted to show different views of a scene or subject, such as before-and-after; sometimes called “lift-the-flaps” or “turn-ups.”

pop-ups—Paper-engineered constructions that rise when pages are turned.

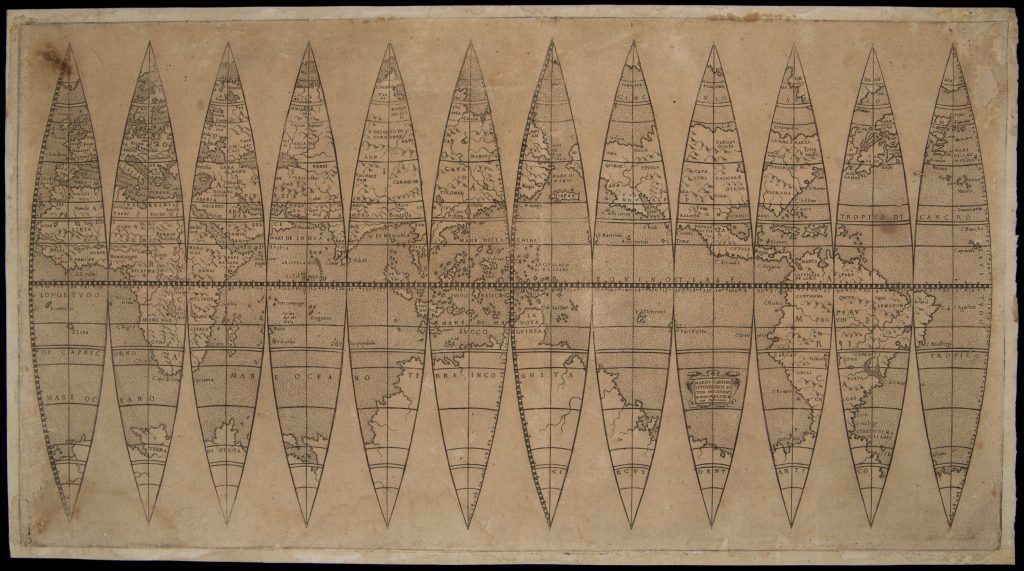

globe gores—Elongated paper strips that can be constructed into a three-dimensional globe of the heavens or the earth. Usually issued in single sheets, they were also collected in albums.

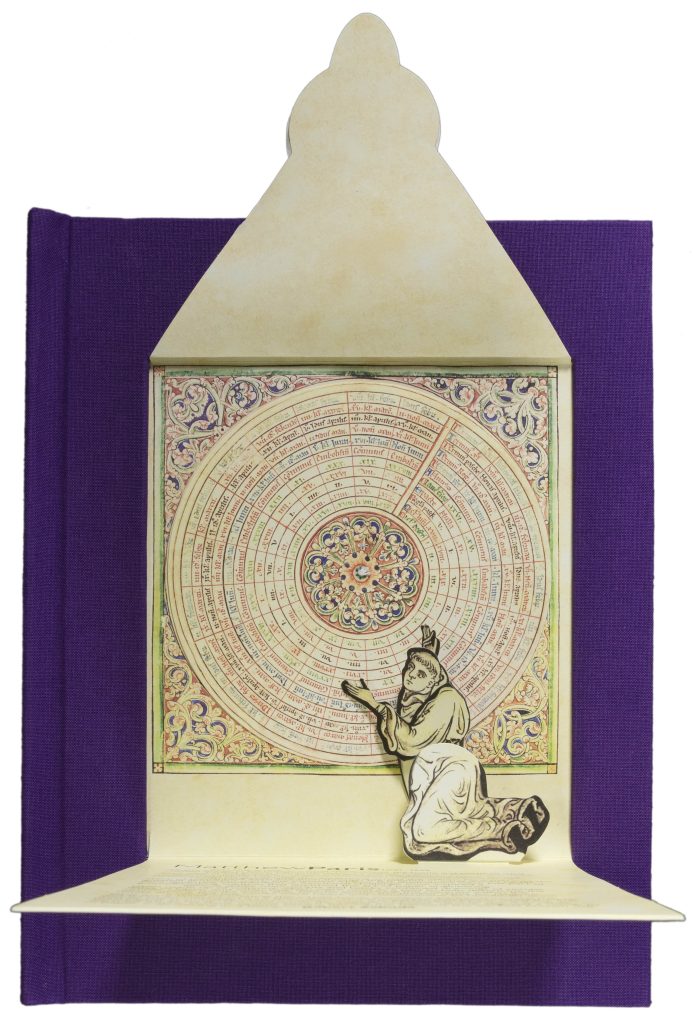

The earliest known surviving manuscript flaps date from 1121 AD, and the earliest volvelle from 1250 AD, with printed movable books, constructable globes, and other formats produced in three dimensions beginning in the late fifteenth century. Dioramas and extendable tunnel books showing three-dimensional scenes appeared during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though the term “pop-up” was not trademarked until 1932.

Movable additions to books over the centuries were made from paper, vellum (animal skin), string, hidden metal coils, and even lead weights. Movable components such as dials, flaps, and pop-up parts were printed on uncut sheets of paper and later as perforated nesting sheets with die-cut (cut by machine) lines for easier assembly. Books using these techniques explored many themes, including religious devotion, science, political theater, entertainment, and artistic inspiration.

Please consider the following questions as you review the documents:

- How long ago did you think the first movable or pop-up books were made before reading this Collection Essay?

- How old were you when you first used a pop-up book? Are they for all ages?

- How are movable or pop-up books different from regular books?

- Paper engineering is a very adaptable artform. But are there topics that cannot or should not appear in pop-ups?

From Scholarship to Entertainment

Who used movable books? The earliest movable books were scholarly, mostly devotional manuscripts written in and preserved by monasteries, which were often solely the domain of men. Renaissance-era mathematicians and artists like Albrecht Dürer dedicated their movable printed teaching manuals to other artists and craftsmen, and used them to impress noble patrons. Male university students might have read one of many editions of Peter Apian’s Cosmography with its dials or cheaper, abbreviated versions of Andreas Vesalius’s Fabrica with its anatomy flap diagrams. Wealthy young men and, increasingly, women too, became audiences for movable books in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, pursuing activities ranging from making predictions with specialized astronomical texts to playing fortune-telling games. By the eighteenth century, some geographical manuals for affluent and literate consumers became explicitly coeducational. Eventually, movable and pop-up books would be marketed equally to male and female readers and intended to reach broader audiences.

The First Dials

The earliest volvelles that we know to have survived appeared as calendars and calculators in thirteenth-century manuscripts, followed by a fifteenth-century print publication boom. German mathematician Johannes Regiomontanus’s Kalender (with the earliest volvelle in a printed book), and Italian scholar Jacobus Publicius’s snake-shaped, movable memorization aid were especially frequently published texts.

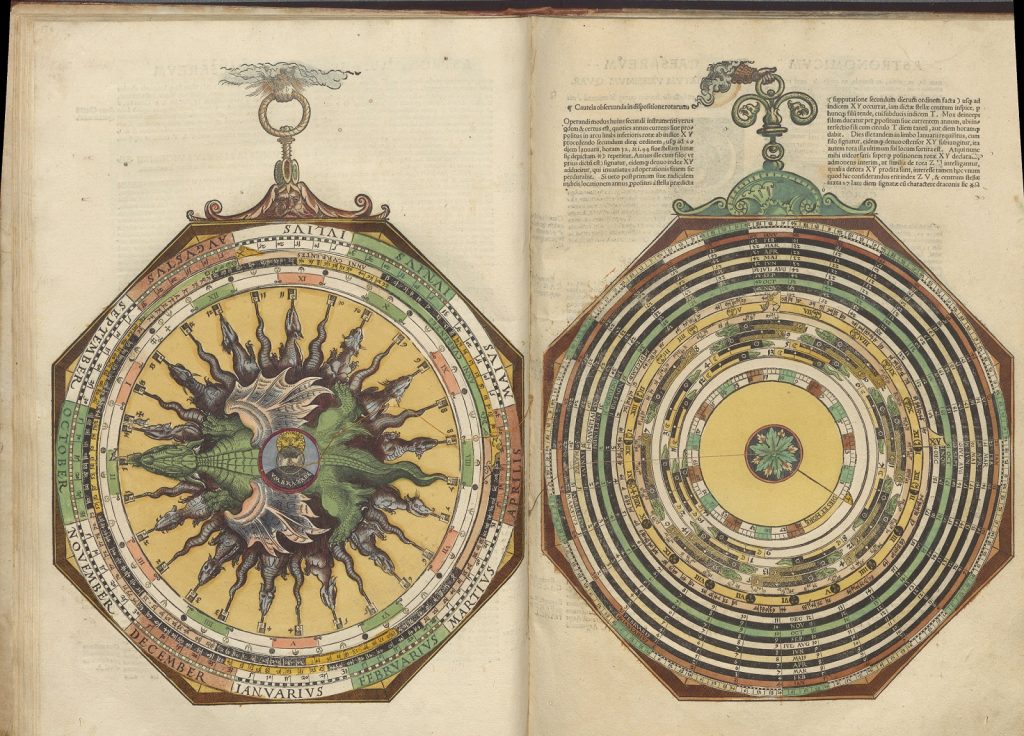

Movable Books Fit for Emperors and Students

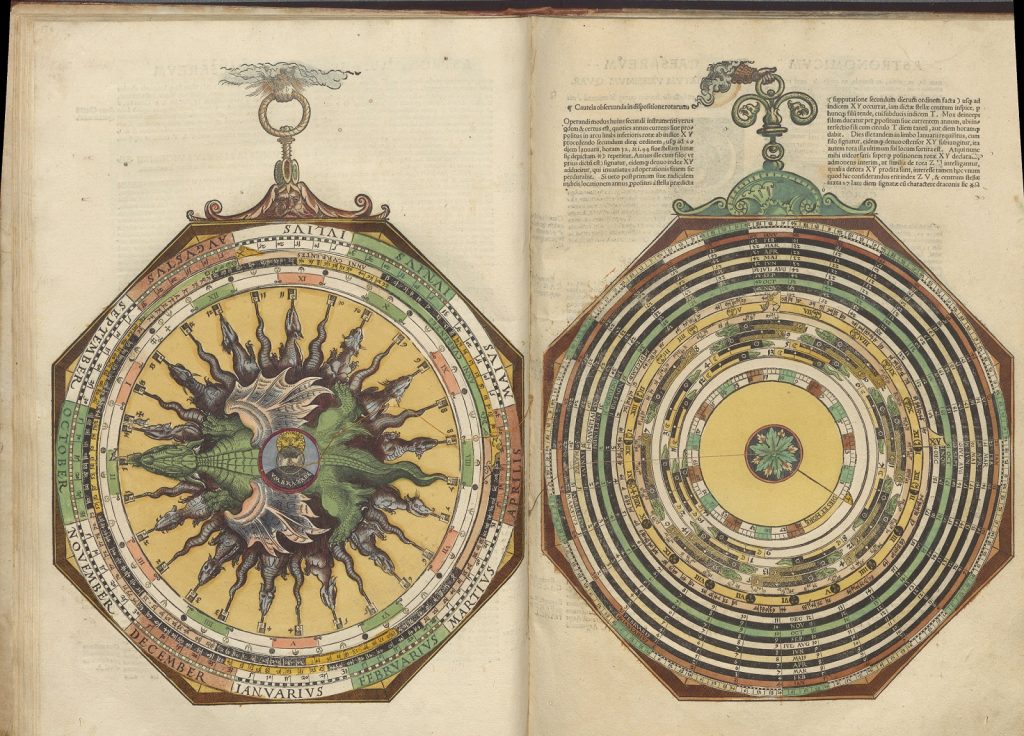

Books with moving parts often pushed print technology to its limits. Perhaps the most lavish movable book, the Astronomicum Caesareum, or Imperial Astronomy, is a brightly hand-colored volume from 1540 that includes twenty-two rotating, full-page astronomical volvelles calculating horoscopes and other measurements. The mathematician, astronomer, and cartographer Peter Apian dedicated it to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who thanked Apian by knighting him. This copy, owned by Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and given to his student, is now at the University of Chicago. It still includes silken index strings and sliding seed pearls to mark the reader’s place. It was also briefly at the Newberry, when the library acquired Louis Silver’s collection in 1964. Yet it was never accessioned, and was sold to help defray the costs of the Silver sale. But Apian also made a more affordable version.

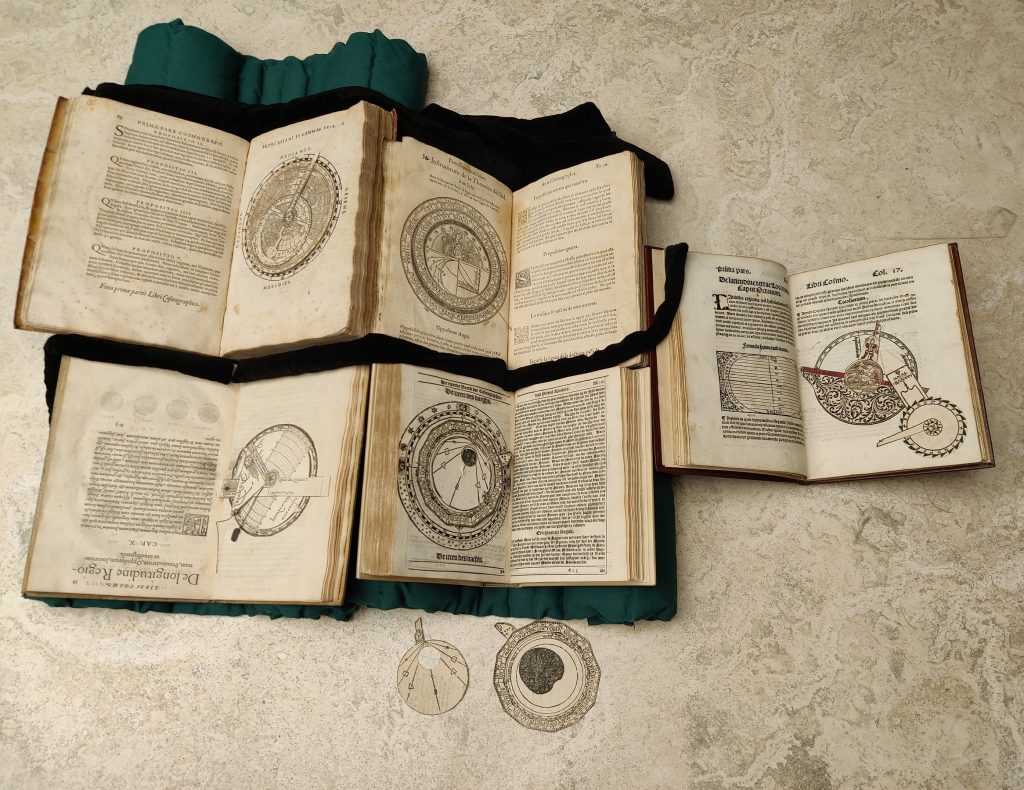

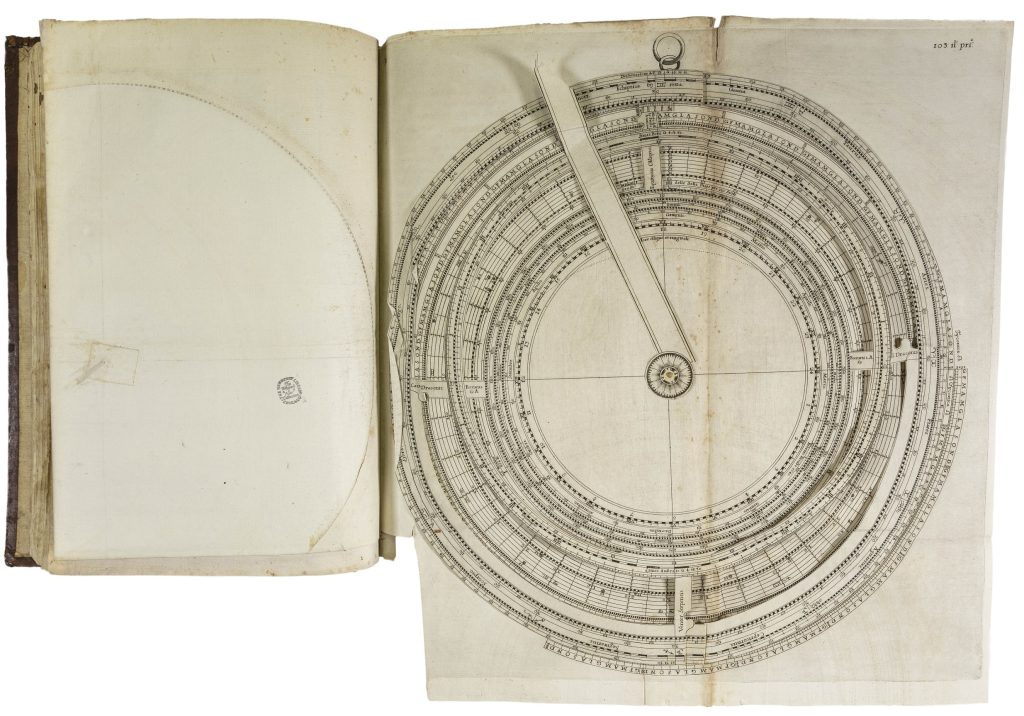

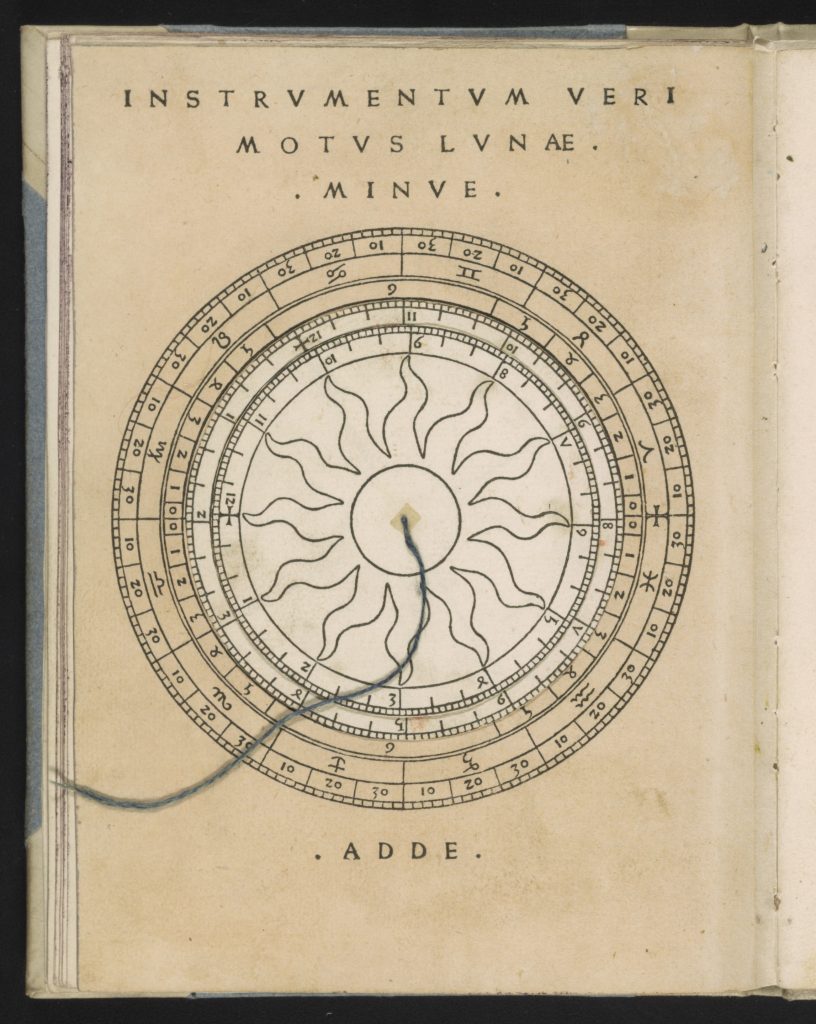

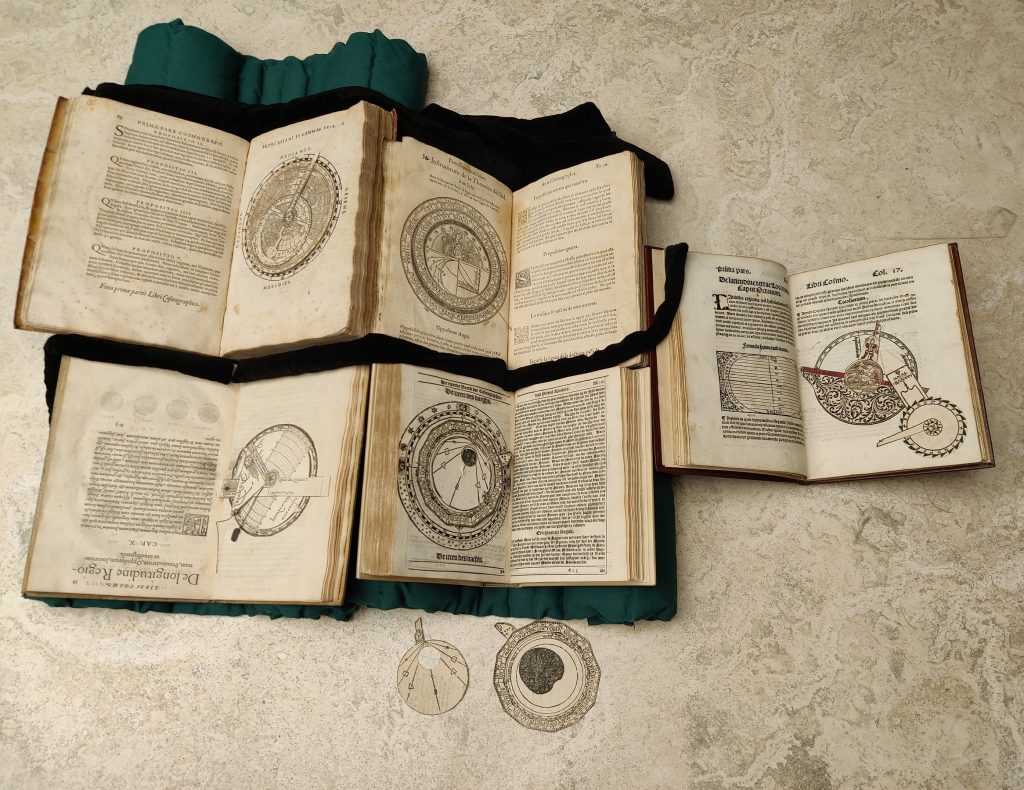

Indeed, thanks to early twentieth century collector Edward E. Ayer, the Newberry contains an unmatched twenty-one copies of Peter Apian’s influential interactive text on cosmography, a popular area of study including navigation, surveying, and timekeeping. The Cosmography includes five interactive instruments: a boat-shaped dial that teaches about latitude and the horizon; a sundial with an index string; a sundial with three movable components and leaded weight on strings that must be consulted upside down; a view of the earth from the North Pole with dials that measure times and locations; and a two-layer lunar volvelle that calculates time by day or night. These stayed the same from the first edition in 1524 to the last in 1609, and appeared in many languages (Dutch, French, Latin, Spanish) and cities (Antwerp, Amsterdam, Landshut, Paris).

Questions to Consider:

- How have the audiences for pop-up books changed over time?

- Can early movable books be considered works of art?

Maps, Globes, and Flaps

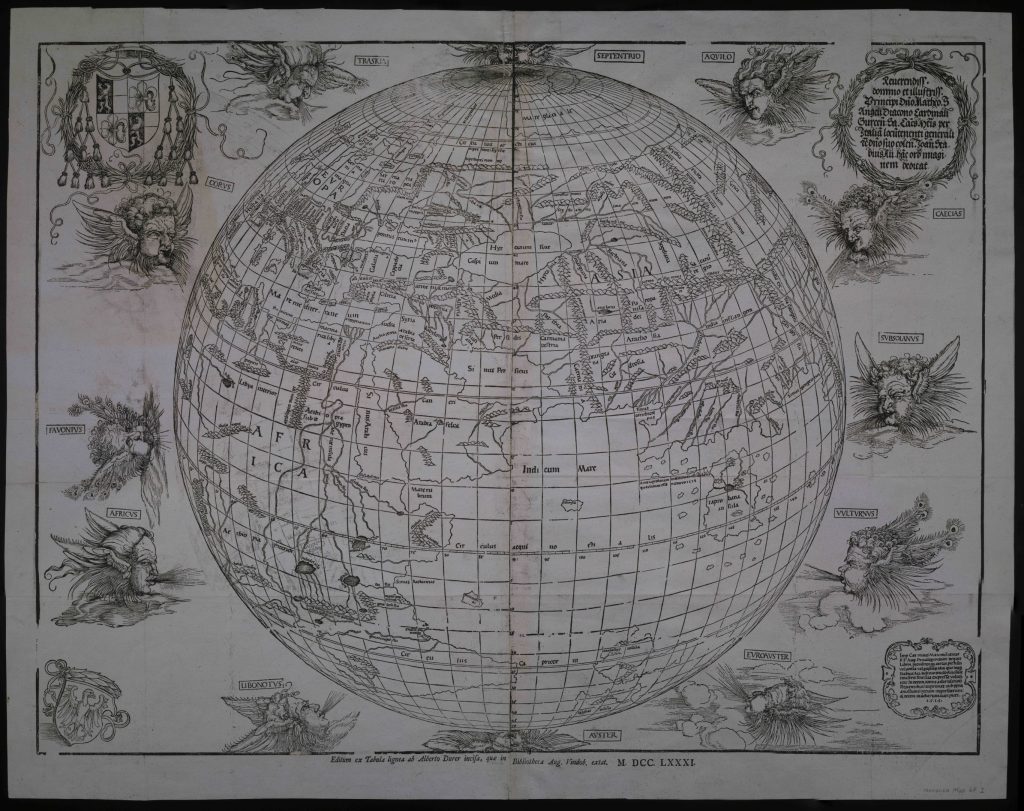

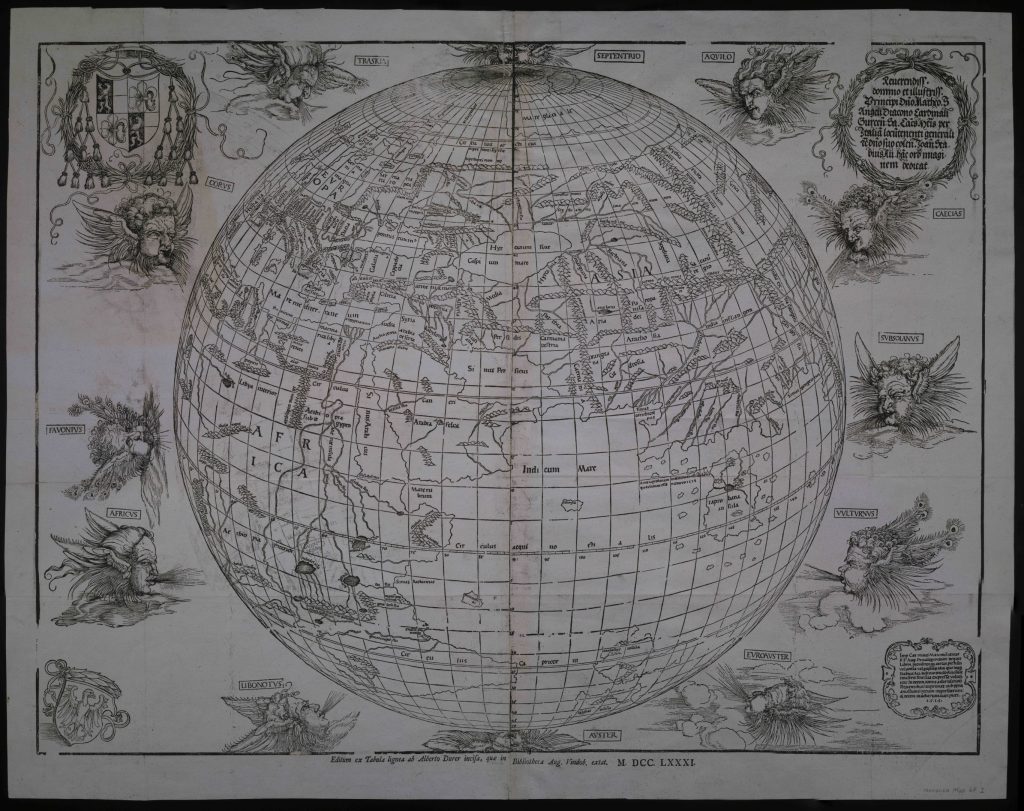

Paper was already three-dimensional during the Renaissance. Globes were constructed from drawn or printed globe gores as early as 1492. These cut-out, elongated strips illustrating sections of the globe were pasted onto a wooden or papier-mâché core. Usually sold in pairs, the spheres depicted both the terrestrial and the celestial realms. Early cartographic paper engineering also included flap depictions of battle movements and before-and-after views of natural disasters, as well as a few volvelles.

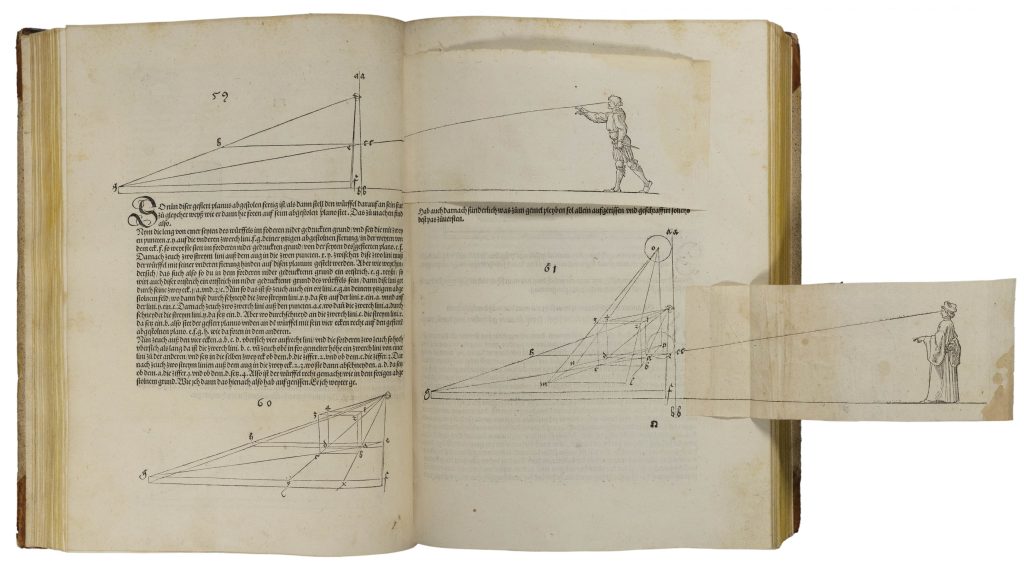

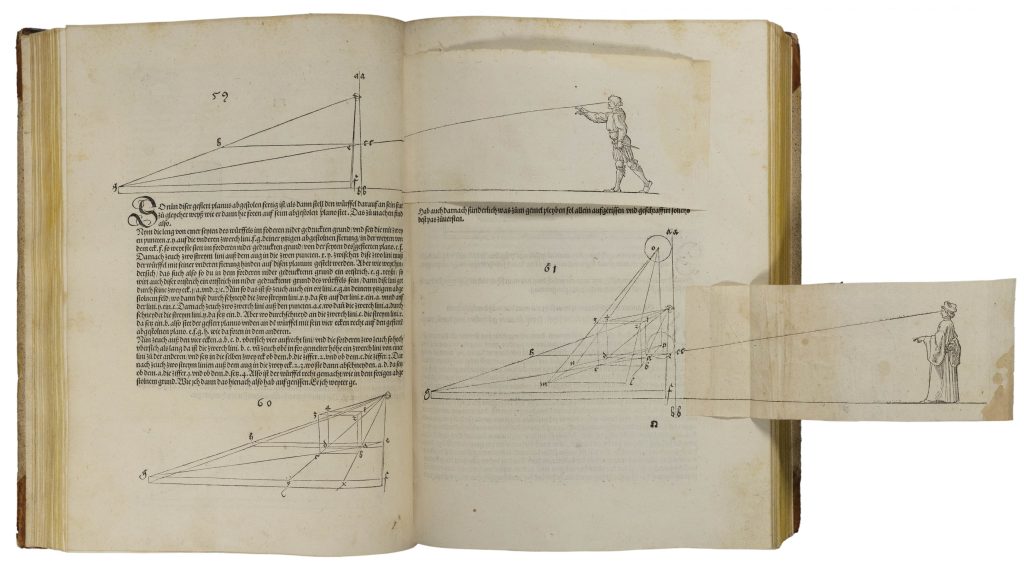

Famous German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer collaborated on several woodcut mapping projects with astronomers for the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian. Unfortunately, no copies of his 1515 World Map that were printed in the sixteenth century survive. Dürer also wrote and illustrated a Manual of Measurement for artists around 1525. Several diagrams in it showed globes in sections, but these were never intended to be cut-out globe gores. Instead, his massive bird’s-eye view map demonstrates the sphere’s volume through perspective. His Manual also included two extendable flaps for diagrams demonstrating the proper use of perspective.

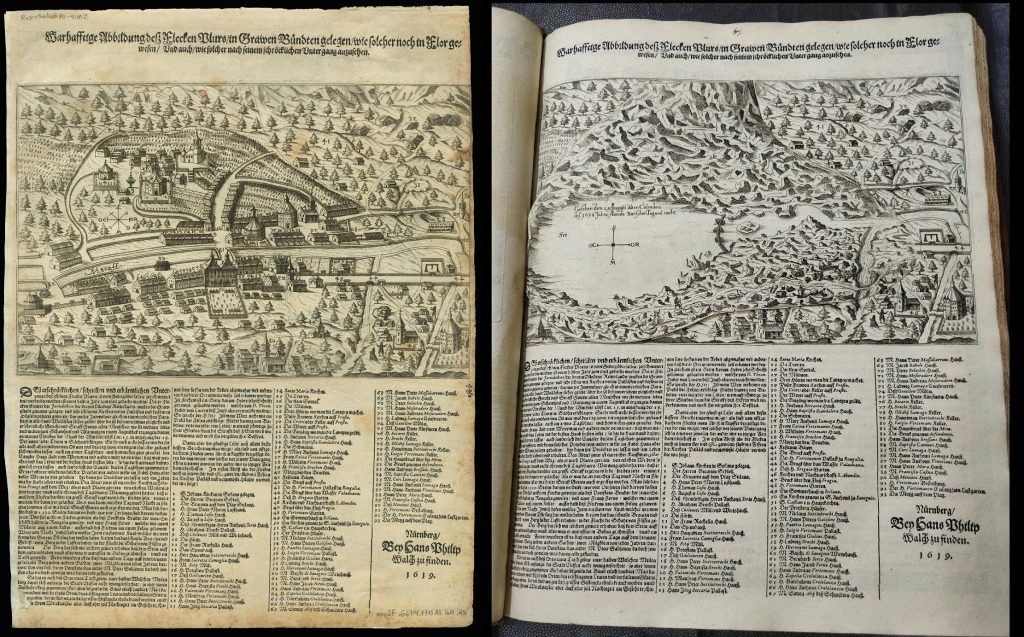

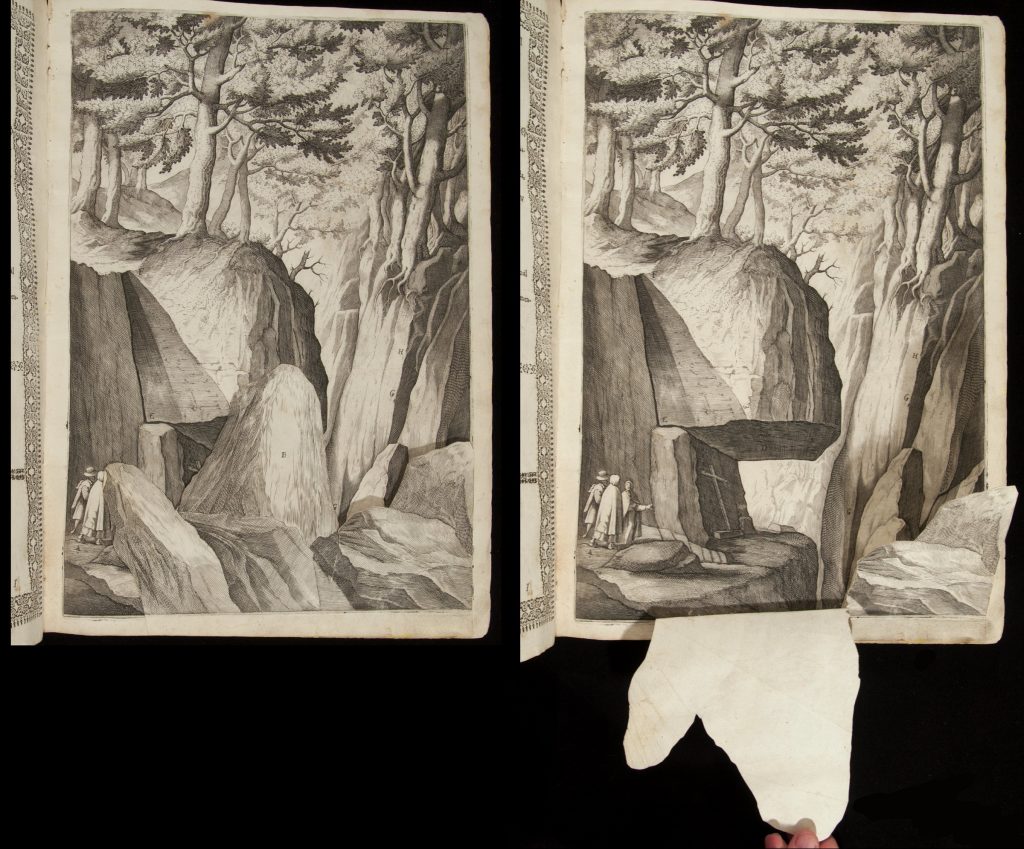

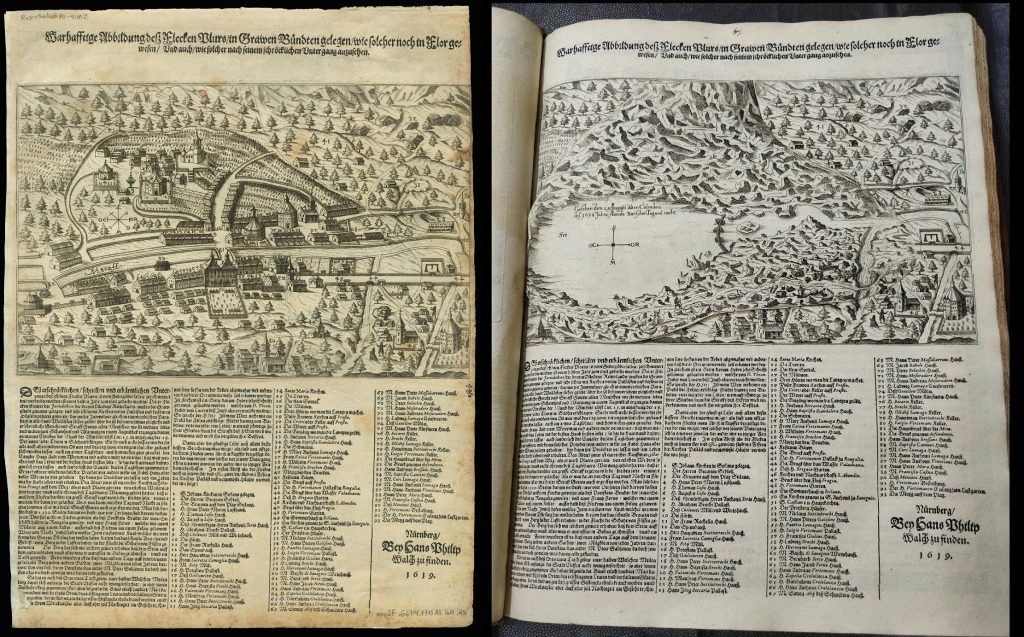

Destruction by Rockslide

What can we learn from a flap that is no longer there? In 1618, Plurs, a prosperous mining town nestled between Italy and Switzerland, fell victim to a sudden and devastating rockslide. This rare broadside once included a glued-on flap of the lake that formed over the destroyed town; bits of red wax and paper at the top show where it was attached. Printed news reports about the disaster ‘went viral,’ and several included this type of flap.

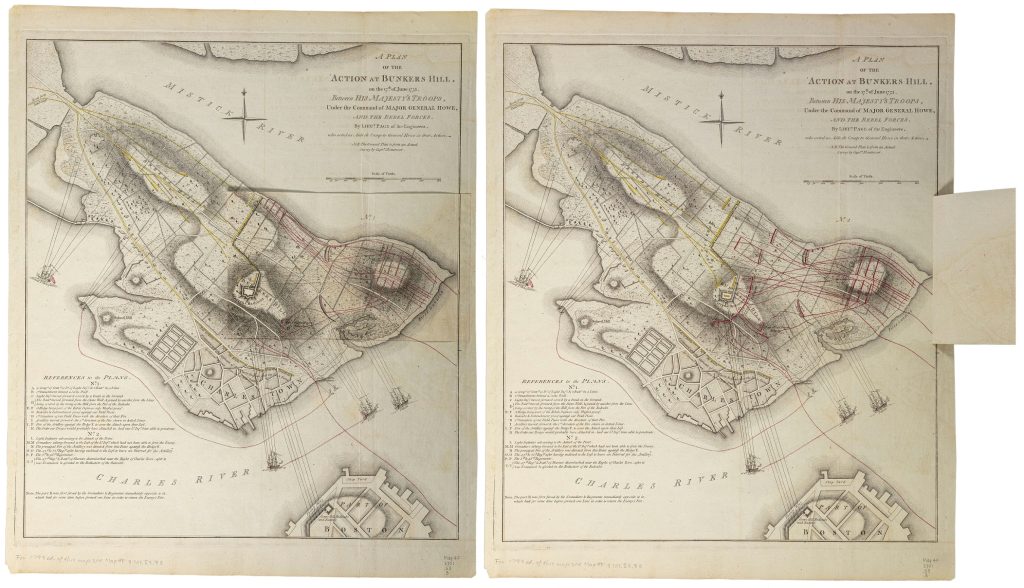

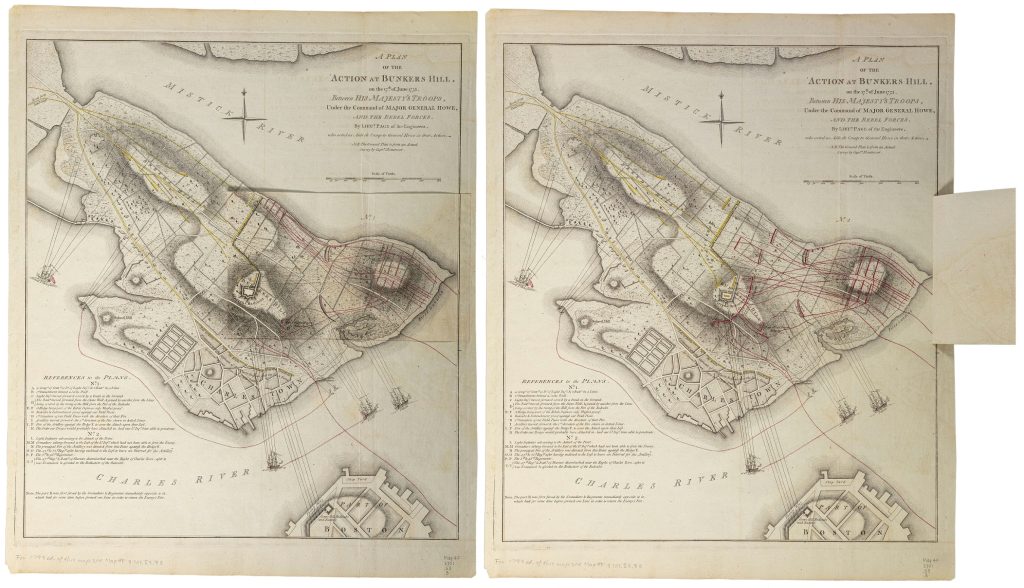

Repositioning the Armies

Several British maps of American Revolutionary War battles included flaps with changing views of troop formations as the armies attacked each other. British officers who served as engineers and cartographers made several interactive maps. The author of this one, Lieutenant Page, was wounded during the British attack in their 1775 victory at Bunker Hill near Boston.

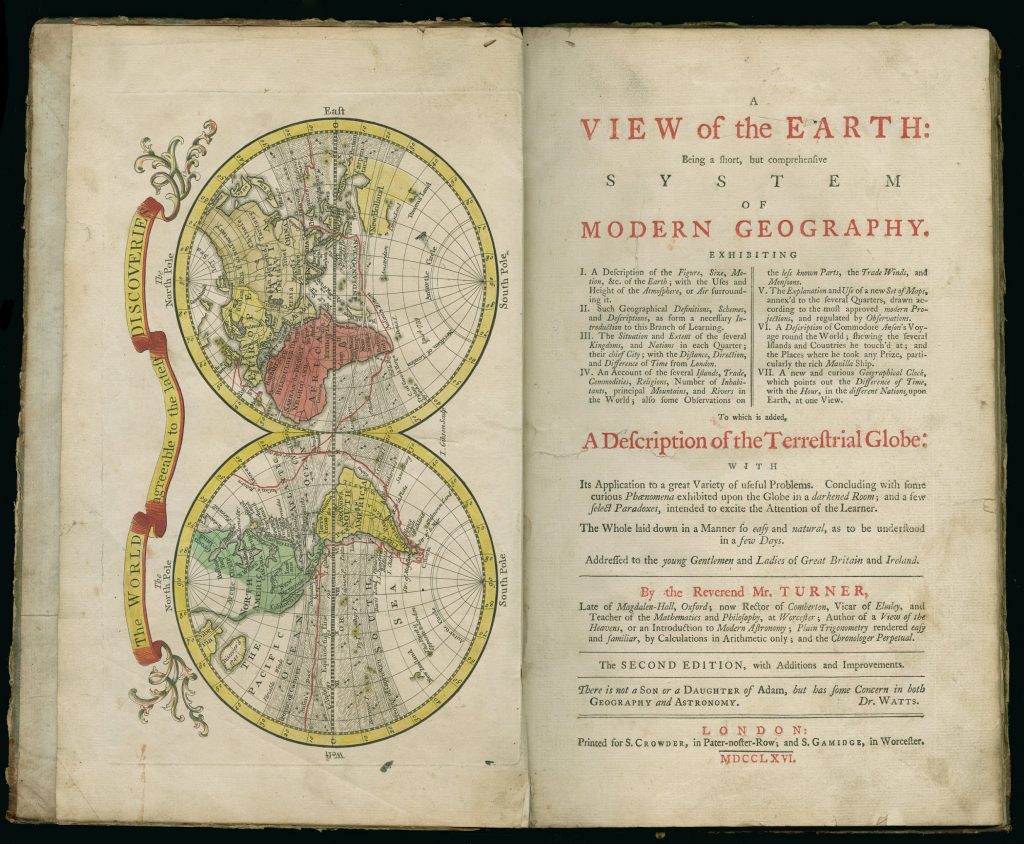

Interactive maps and globes continued to be used in the classroom and in homeschooling into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This included many of the subjects we now know as the sciences, such as anatomy, astronomy, geometry, geography, and mathematics. A very popular series by Richard Turner was geared to learners of all genders, with the title A View of the Earth: Being a short, but comprehensive system of Modern Geography. First published in 1762 and still in print in an expanded format by 1810, it was “Addressed to the young Gentlemen and Ladies of Great Britain and Ireland. It included a so-called geographical clock with a rotating dial. Indeed, it must have succeeded, as Turner also published a book of astronomy entitled A View of the Heavens with a matching volvelle of celestial imagery!

Selection: Richard Turner, A View of the Earth: Being a Short, but Comprehensive System of Modern Geography, title page and frontispiece and volvelle of geographical clock (1766)

Questions to Consider:

- Early print rarely survives to the present, especially books with moving parts. What records of news that affect your lives today might be lost in the future?

- What school topics would pop-ups make more interesting today?

Putting It Together: From Do-It-Yourself to Preassembled Books

Novelty was a major motivation for marketing movable books. Yet early modern publishers were initially hesitant to offer fragile dials or flap additions, leaving their construction in the hands of the buyers and bookbinders who assembled the sheets into codices (bound volumes). Because of this, many copies remain unconstructed. The most complicated movable books and presentation copies, however, usually would have come preassembled. By the nineteenth century and with the advent of publishers’ bindings, movable book formats became more available, while also trending toward more robust offerings for children. This provided the opportunity for ephemeral (single-use), pamphlet-like printed souvenirs of dramatic theater performances, recreations of architecture and scenery, and even valentines proffering fold-out bouquets. More recently, innovations in paper engineering have emboldened bookmaking artists to adapt older techniques in new, structurally ambitious ways.

Skin Deep?

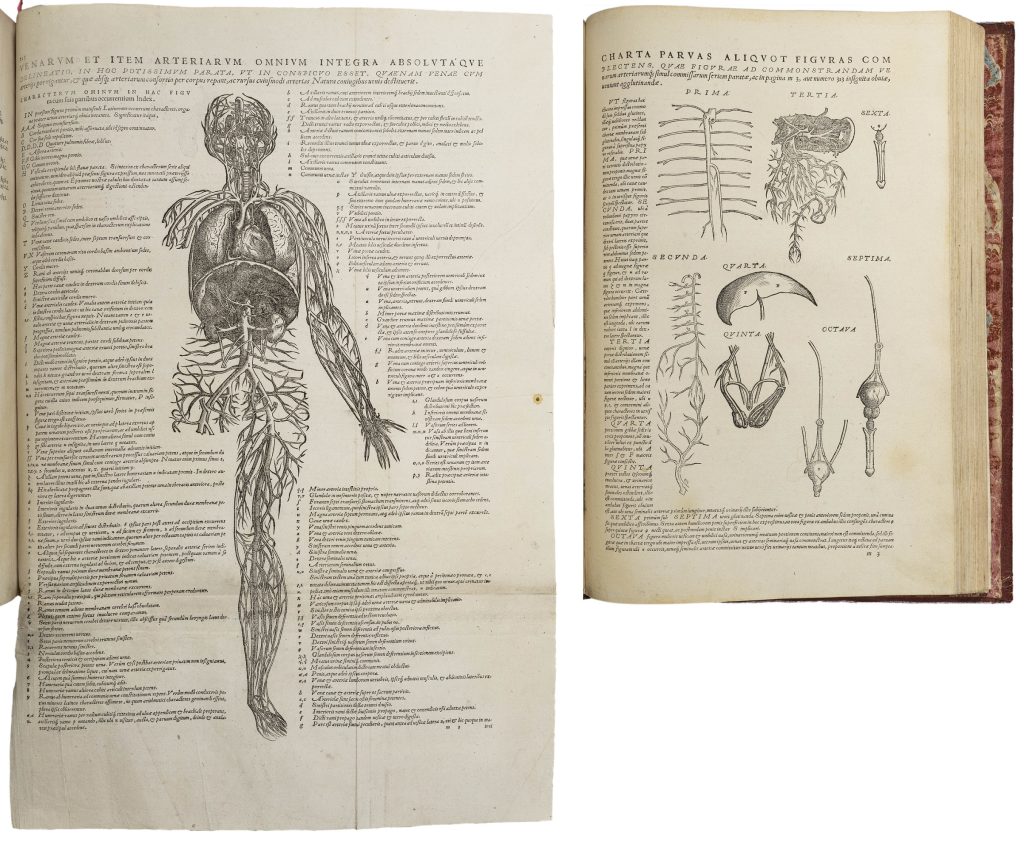

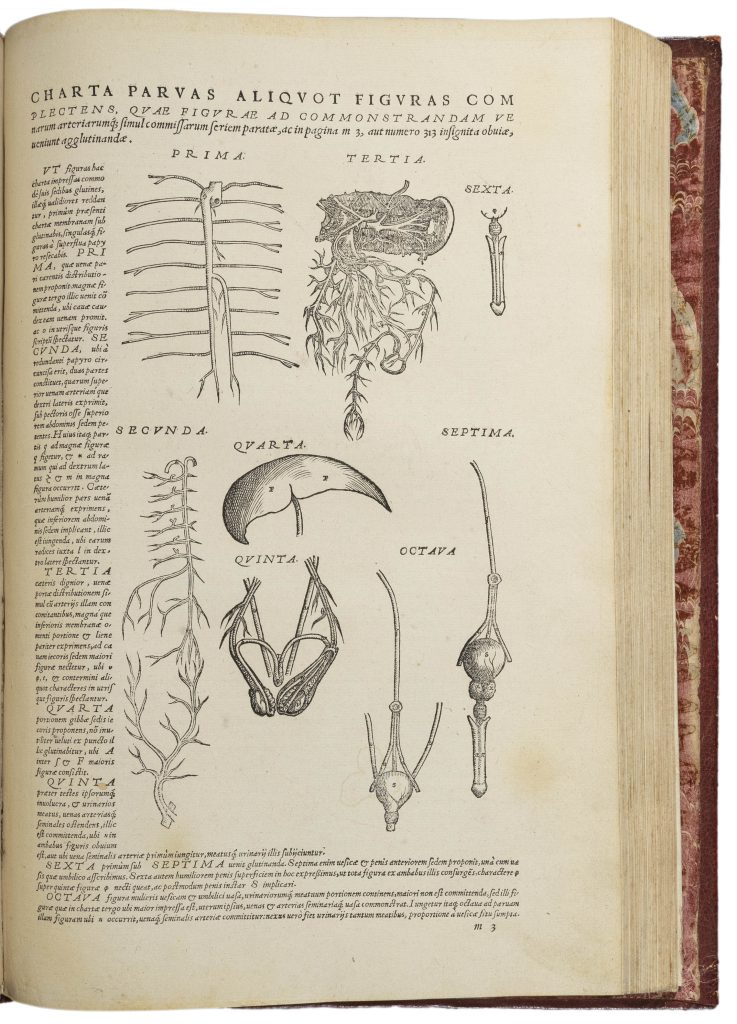

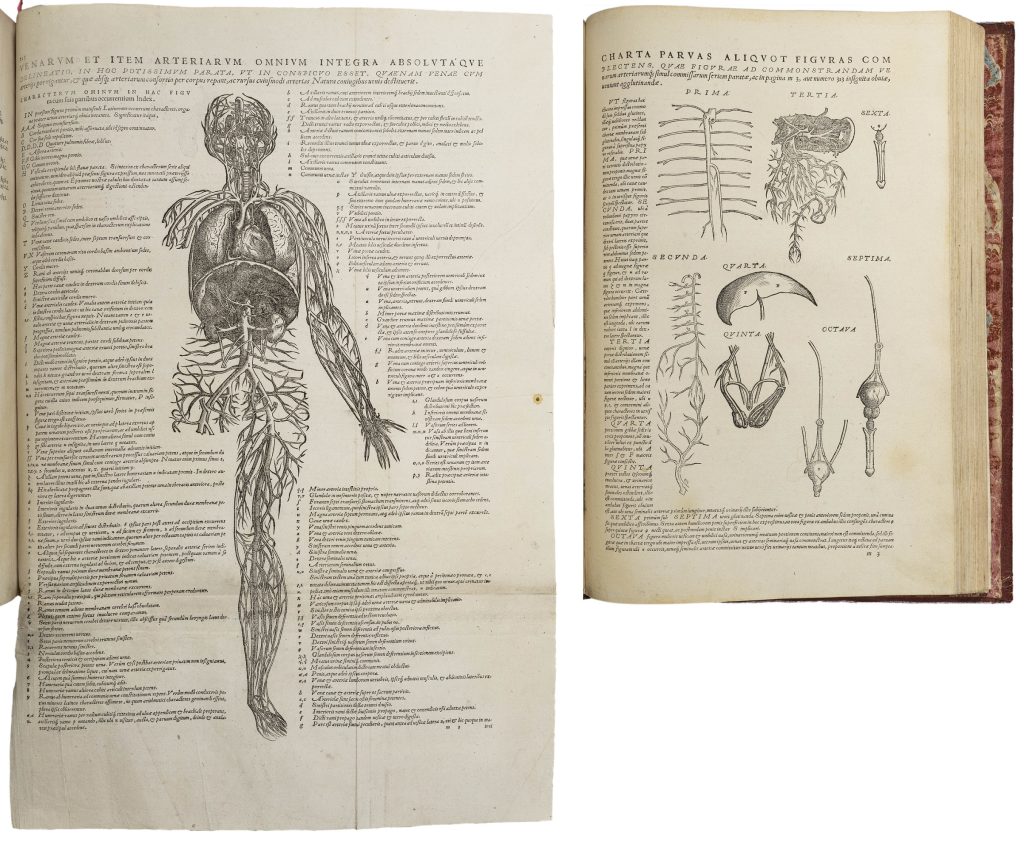

Anatomical flap prints and interactive book illustrations became popular teaching tools in the sixteenth century. Andreas Vesalius taught medical students about dissection with them. His book came with a fold-out broadside of the human body with a separate sheet of organs for the owner to cut out and place on it. A cheaper student version was also available. This hands-on technique continued to develop, with a full-color printed pinnacle in Gustav Joseph Witkowski’s oversized eye model. While Vesalius included notes on the best way to reinforce each organ, the variety of materials comprising Witkowski’s eyeball—and the lack of instructions—made it likely too complicated to have been built by the buyer. And so, it would have been sold preassembled.

Binding Bloopers and Awkward Additions

Early modern movable books were sold as unbound sheets, and amateur construction attempts often failed. One of the Newberry’s Peter Apian Cosmography books has the wrong parts bound into its second diagram. And an inattentive bookbinder bound Robert Dudley’s ambitious seventeenth-century atlas too tightly for his volvelles to function; they now fold in on themselves too closely to turn.

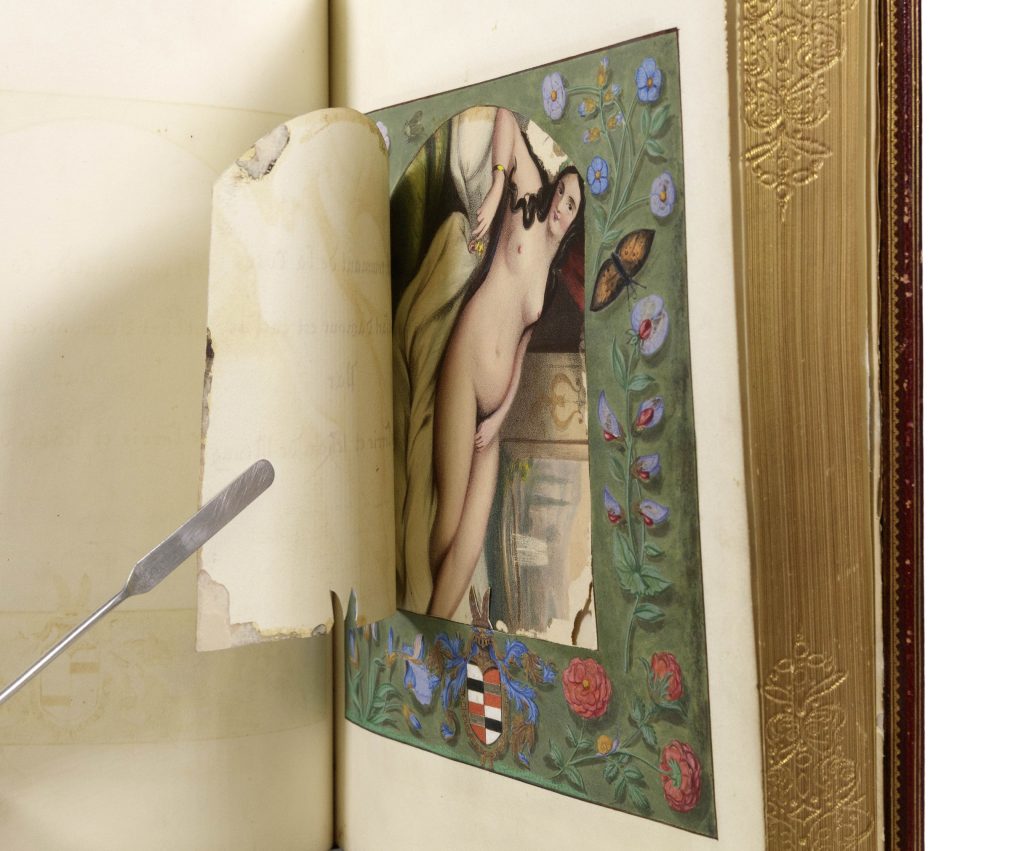

Another collector, who might or might not be the nineteenth-century collector Henry Probasco who sold the book to the Newberry, secreted two prints of naked women into this modern version of the famous fifteenth-century poem Roman de la Rose about chivalric love.

Selection: Guillaume de Lorris, author; Jean de Meun, author; Octave Delpierre, compiler, Cy est le Rommant de la Rose, ou Tout l’Art d’Amour est Enclose (Here is the “Roman de la Rose,” in which all the art of love is enclosed), first image and second image (1848)

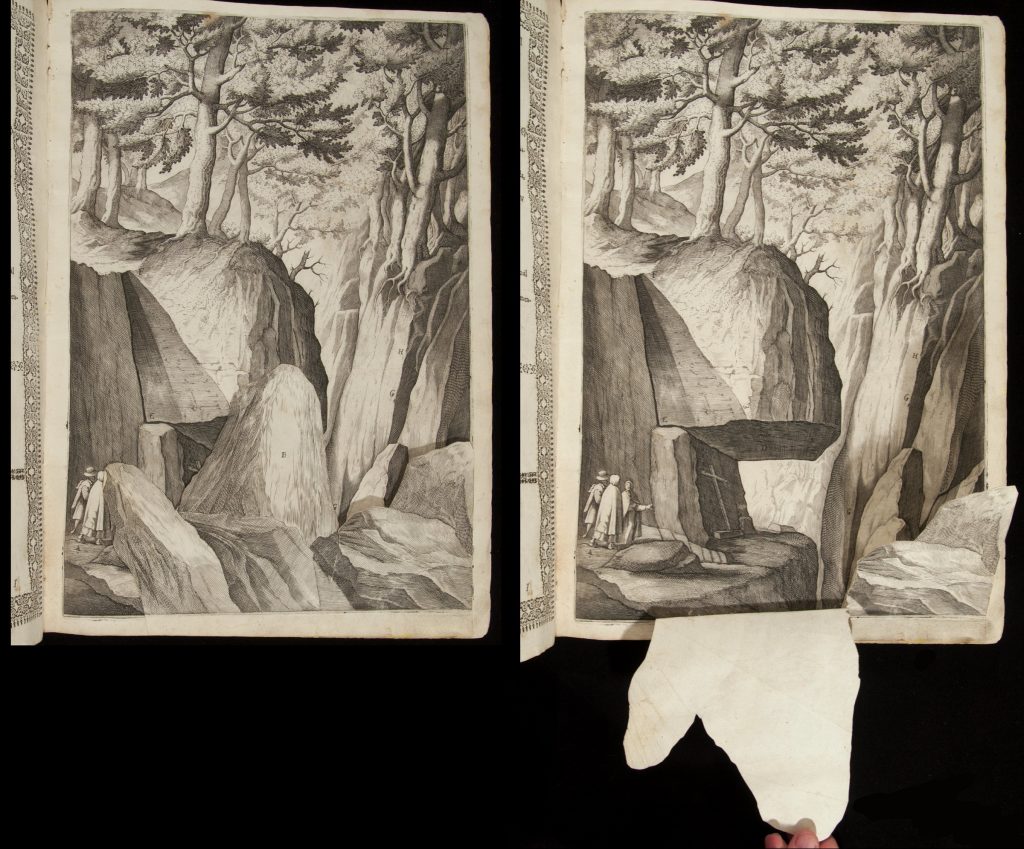

Taking an Armchair Pilgrimage

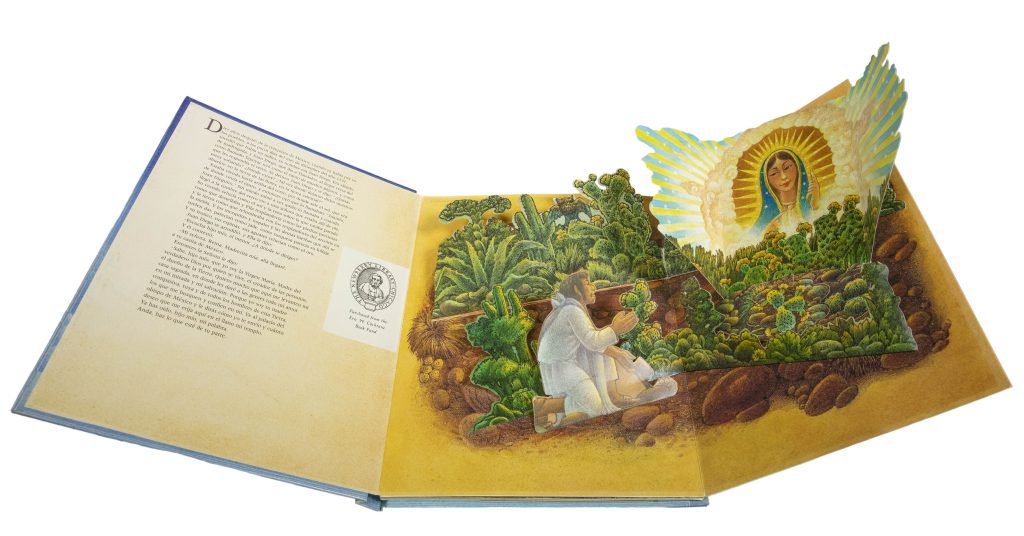

Miracles can happen between the pages of pop-up books. The pages of two movable books published over three hundred years apart reveal Saint Francis’s thirteenth-century vocation and the 1531 discovery of the Virgin of Guadalupe in similar ways. In a 1612 pilgrimage guide to the Italian holy mountain where Saint Francis received a vision of wounds like Christ’s, the liftable flaps granted hands-on access to Francis’s devotional journey.

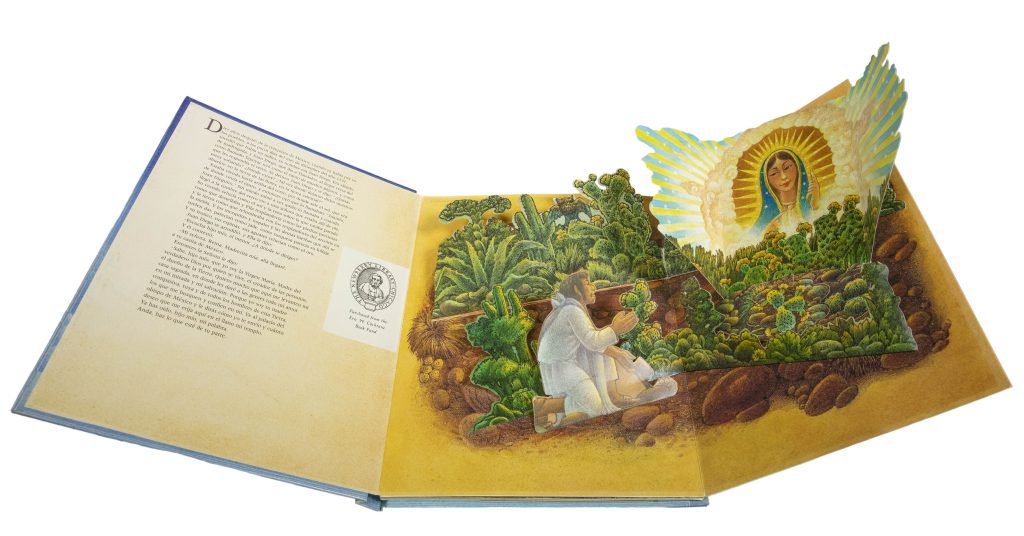

In a 1998 pop-up you encounter the vision of the Virgin with peasant Juan Diego in his village near Mexico City in three dimensions. Both books were assembled before purchase, and the construction was done by hand.

Questions to Consider:

- How can moving parts help immerse the reader in an historical event, or help them relive it? What other disasters would work this way? Pompeii? The Titanic?

- Personalizing collections can be about more than gathering all of one kind of thing, making a list, or signing your name on each object. Sometimes adding unusual touches makes them unique. How would you make a collection (of books–pop-up or not—or other things) your own? What about other items your own?

Moving into Three Dimensions and Modernity

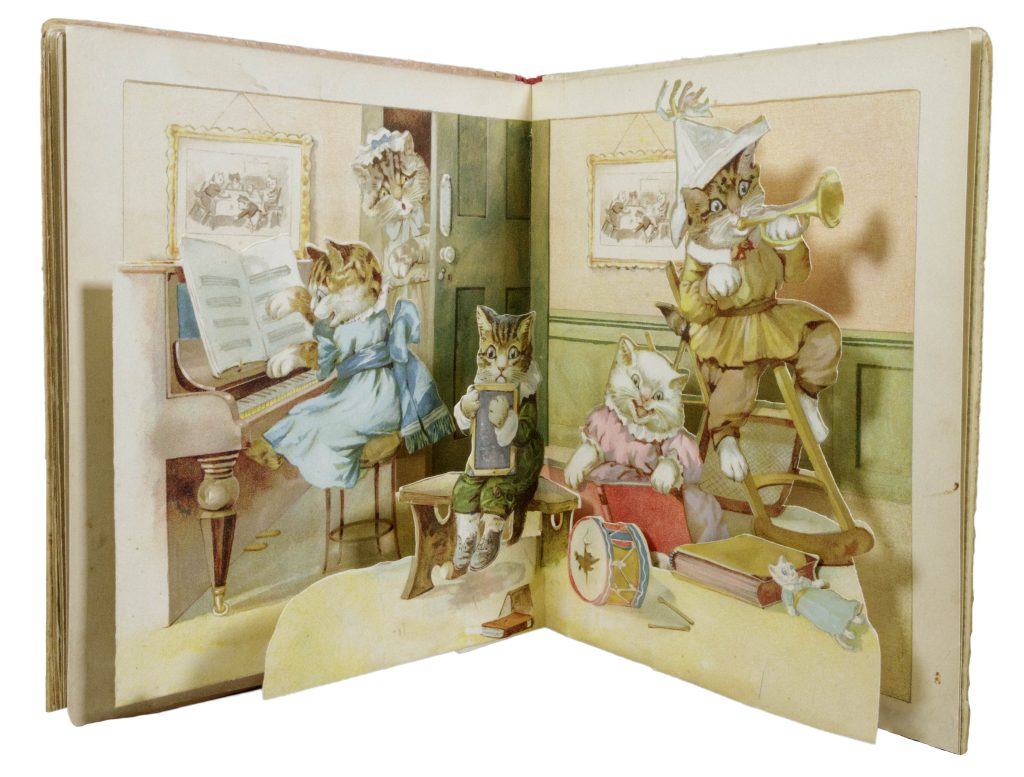

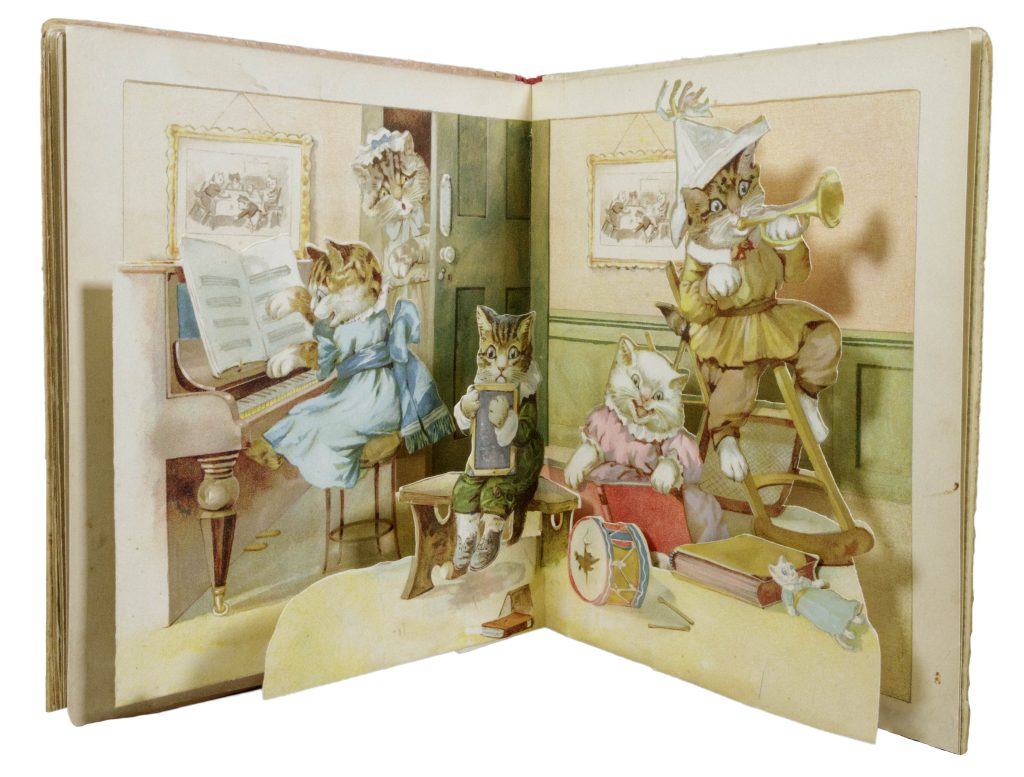

A charming, colorful scene of a group of kittens misbehaving (instead of learning their lessons) is probably what most people think of as pop-up books. Meme-worthy today, it was already being mass-produced in the nineteenth century by German publisher Ernst Nister, who had a keen business sense for movable books, and quickly expanded into English and other markets.

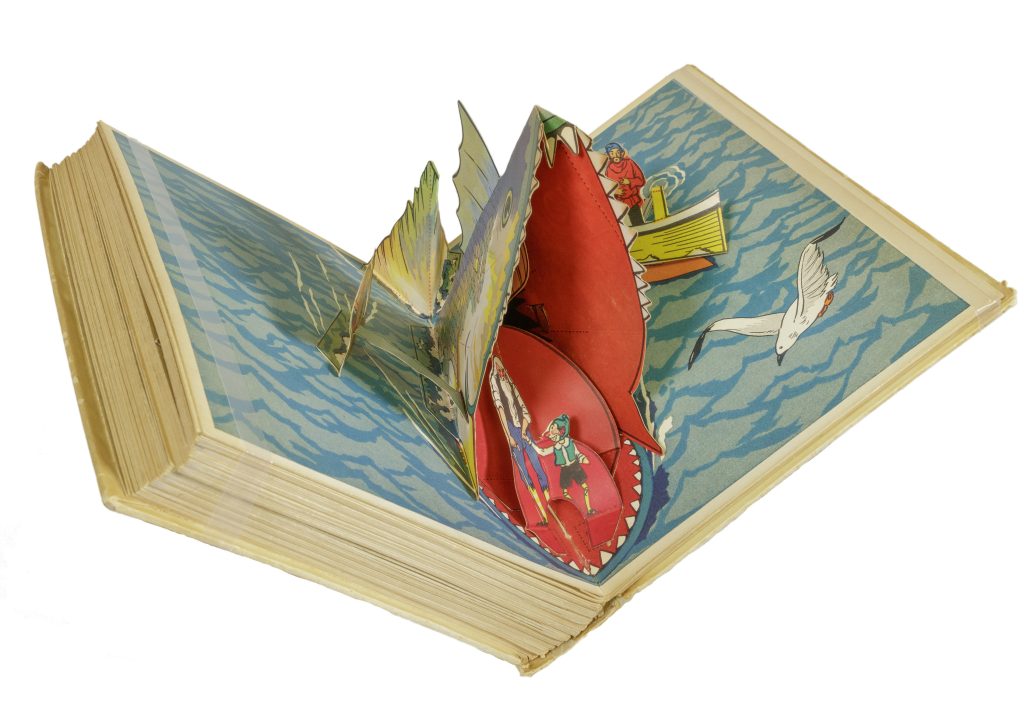

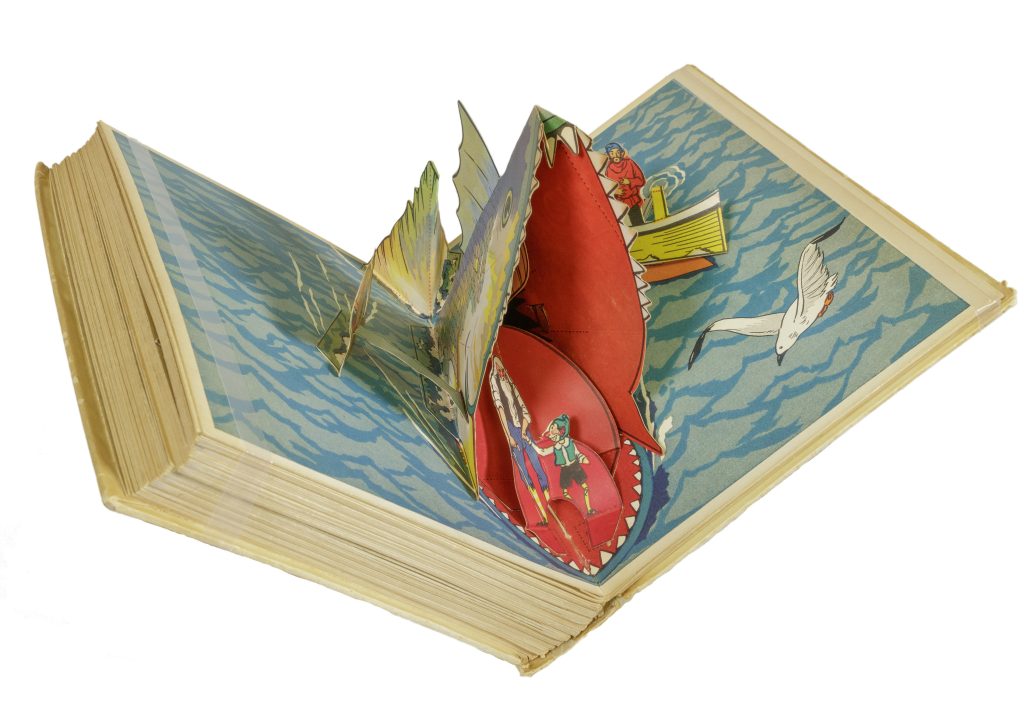

Long after the naughty Nister kittens, Blue Ribbon Books was the first to trademark the term “pop-up” and published a series of movable books in the 1930s, starting with their 1932 “Pop-Up” Pinocchio. Harold Lentz designed four sections with thicker paper to support the structures. Pinocchio reads in his playroom, encounters the Blue Fairy, plays hooky at a circus, and emerges with Geppetto from the belly of a whale-like “dogfish.” The series was extremely popular, and their covers repeated the newly trademarked terminology of “pop-up” or “pop-up illustrations” with gusto.

Optical Illusions.

While creating depth, movable books can also fool the eye. One eighteenth-century magician’s trick “blow book” or “flick book” looks blank until the performer breathes life into it. The different sections are operated by tabs; this one includes colorful stock engravings of flowers, nuns, and soldiers. Later moving flap books created optical illusions through cut-out layers. Benjamin Sands’s popular Metamorphosis conjoins Adam and Eve with a mermaid’s tail, a lion with a griffin, and other surprises. Pop-up pioneer Lothar Meggendorfer’s zany aunt exhibits ever-changing uncouth behaviors from smoking to seduction as the viewer flips through the slices of the page. (In the 1890s, women who smoked were considered truly modern and risqué!)

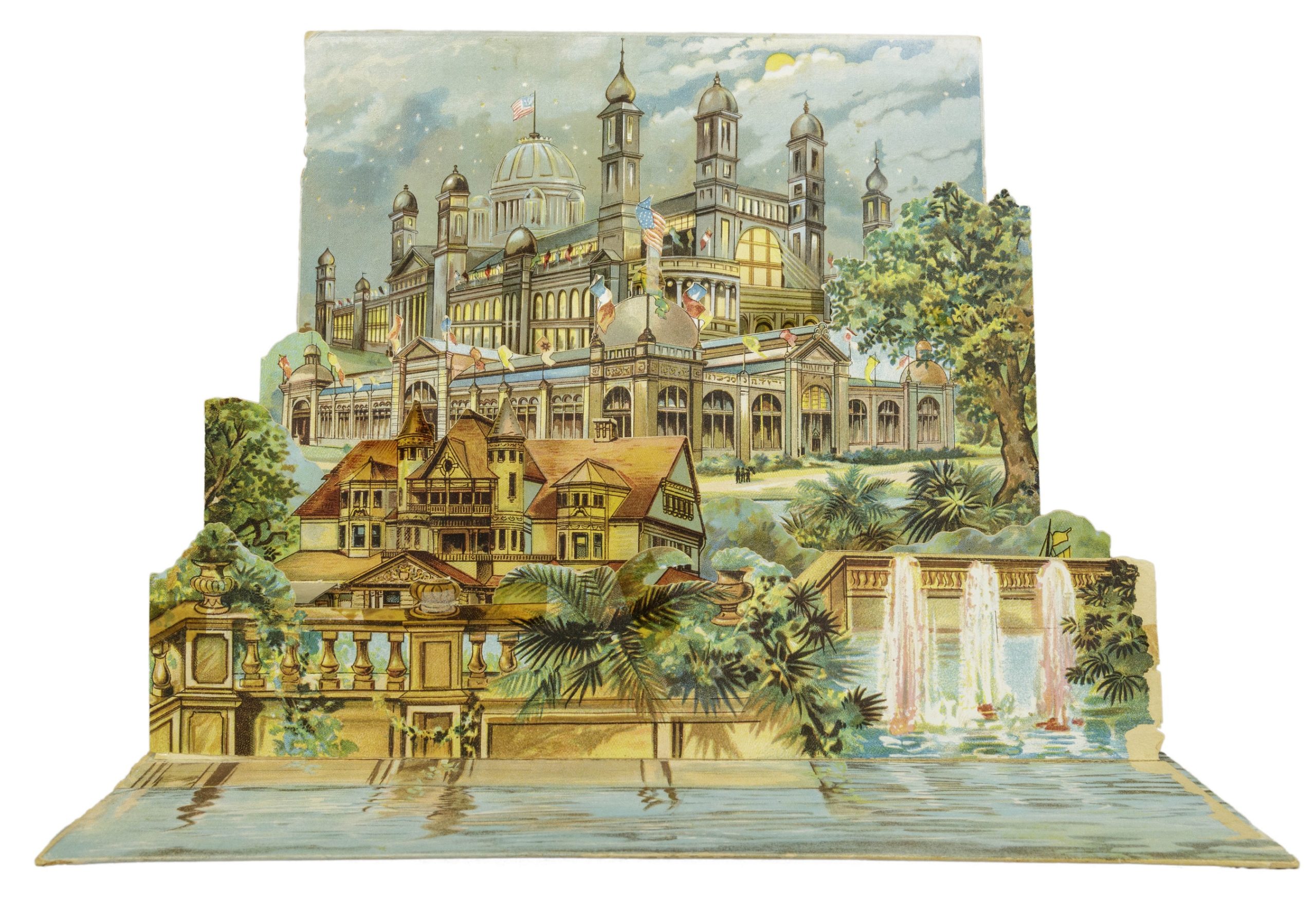

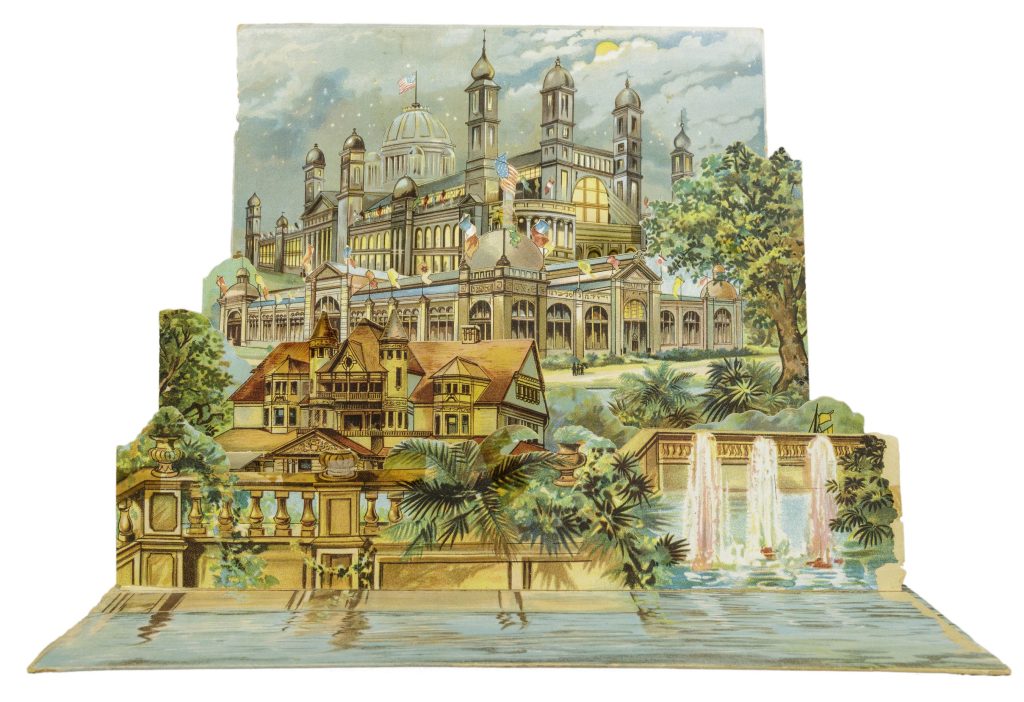

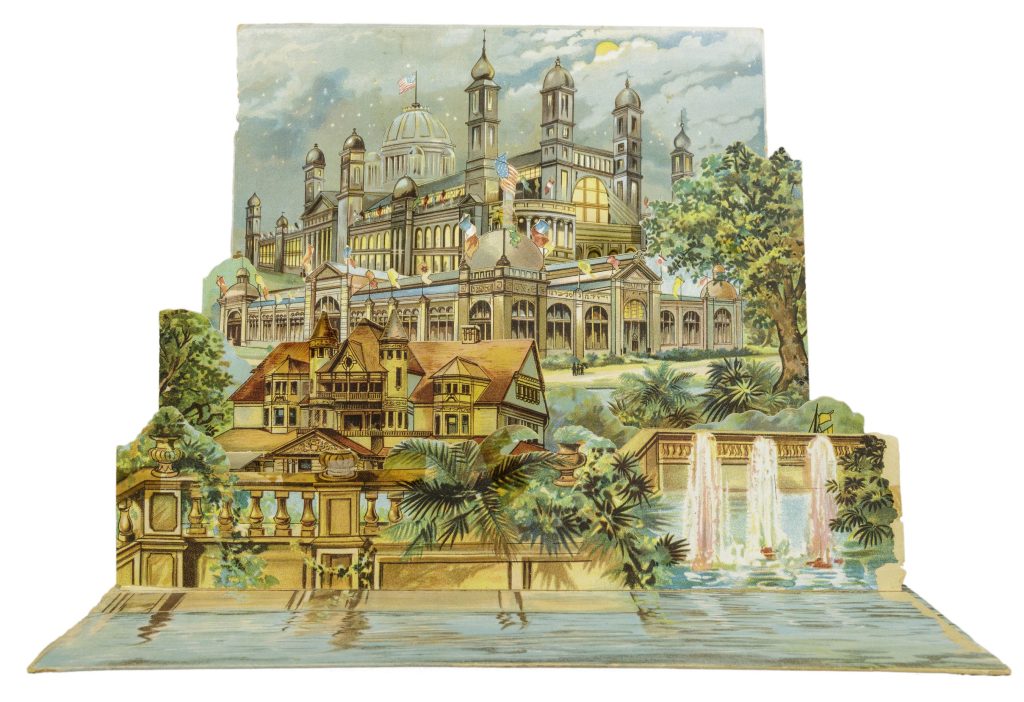

Several three-dimensional book genres emerged in the nineteenth century, including panoramas and tunnel books. These architectural structures frame theatrical and intimate glimpses into hidden or forbidden realms, some of which relate to Chicago. Carousel books open from a closed binding, creating an experience in the round. Hannah Batsel’s carousel channels science fiction, missed love connections, and big city isolation. The stepped-back view of the 1893 Columbian Exposition creates a similar vantage point to Don Widmer’s tunnel-book murder mystery set in Chicago’s Glessner House mansion.

Finally, How Do You Make a Modern Pop-Up? Answer: Still by Hand!

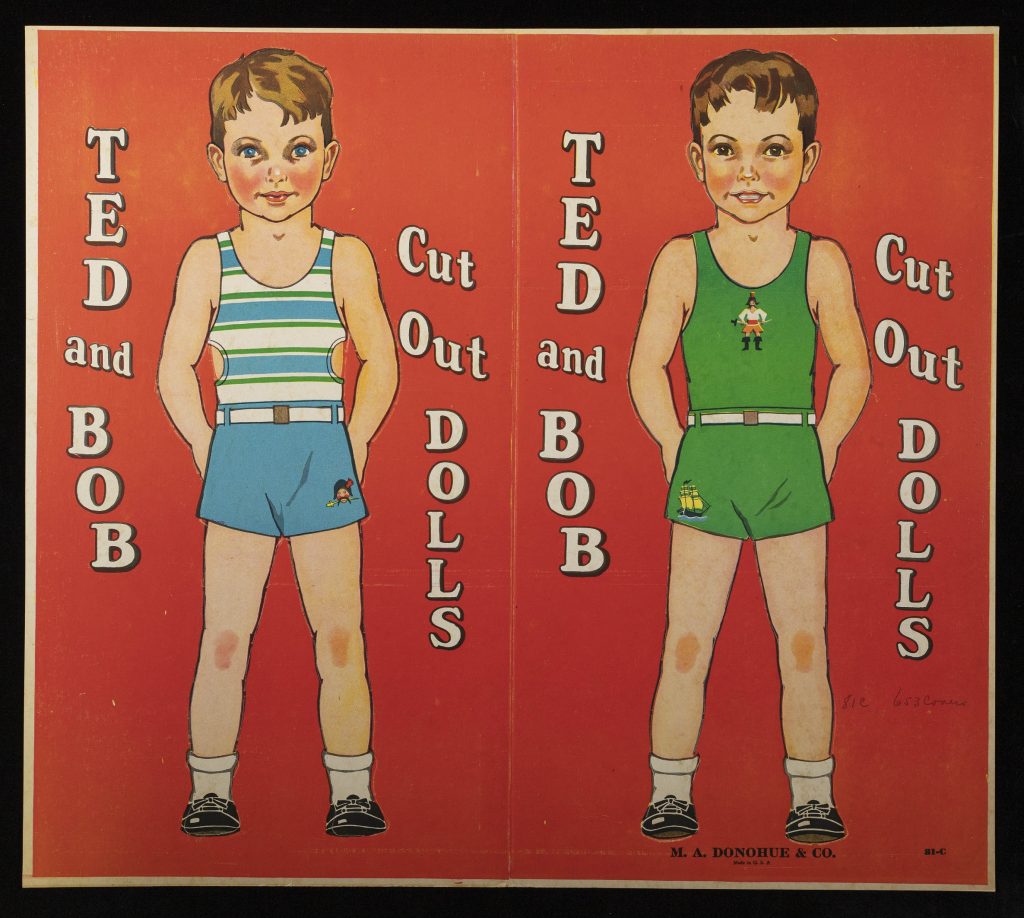

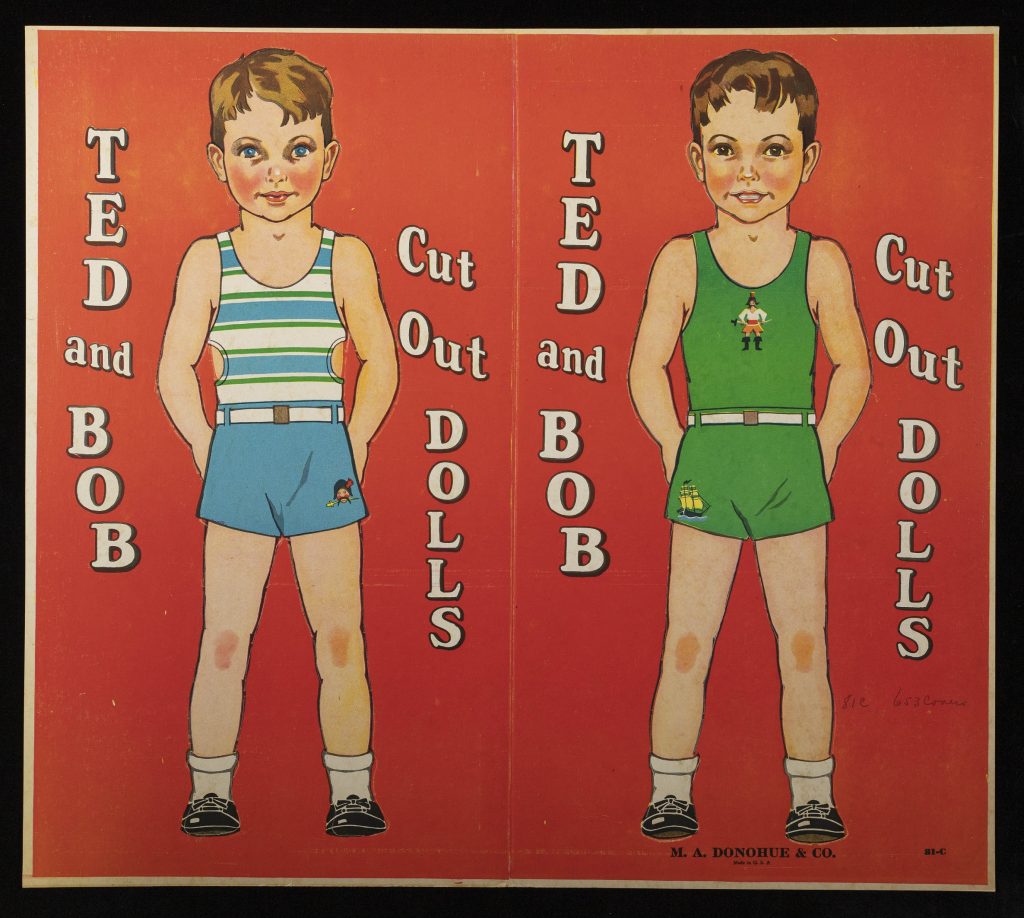

Paper dolls are a relatively simple example of how much easier movable book production became once the parts were pre-cut. For instance, by the 1950s, M. A. Donohue published children’s books and ephemera from offices in Chicago and New York. The firm’s nesting-sheets’ dolls featuring the latest children’s fashions were sold in partially perforated sheets. Customers simply had to punch them out for play. A more advanced, computerized method, laser cutting, was used for the DIY pop-up Newberry kit collaboratively designed by paper engineer Shawn Sheehy and illustrator Hannah Batsel.

Questions to Consider:

- Recent pop-up books tend to be either mass produced with many thousands of copies, or artist books in a few hundred. What are the benefits of both?

- If paper dolls are produced using the same technologies as pop-up books, are pop-up books a type of game? What other books might be considered games? And how does approaching books as ‘games’ change your idea of a book’s possible purpose?

About the Author

Suzanne Karr Schmidt (PhD Yale) has been the George Amos Poole III Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at Chicago’s Newberry Library since 2017, following eight years as a fellow and curator in Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago. A historian of early modern art, books, prints, and science, her monograph, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance, appeared in 2018. She publishes widely on hybridity and materiality in print, particularly on the “Renaissance Pop-Up Book.” Expanding her movable books range up to the present, she has most recently curated the playful Newberry exhibition, Pop-Up Books Through the Ages (March 21-July 15, 2023), which examines this overlooked artform from the medieval to the modern era. Her previous prizewinning shows include her co-curated 2020 Newberry exhibition Renaissance Invention: Stradanus’s Nova Reperta (read the related Collection Essay here), and her 2011 Art Institute of Chicago exhibition Altered and Adorned: Using Renaissance Prints in Daily Life.

Further Reading

Suzanne Karr Schmidt, “Navigating the Hybrid Book,” Guild of Bookworkers newsletter no. 22 (June 2022): 25-28.

Ellen G. K. Rubin (the Pop-Up Lady).

Ann Staples Montenaro, Pop-up and Movable Books: A Bibliography (1993-2000).