Introduction

On January 27th, 1567, Alvar Gonzalez from Campanario, Spain, received the good news he was waiting for. The Chancellery Court of Granada publicly declared him an hidalgo (“nobleman”). Alvar Gonzalez had completed a long and expensive legal process to be recognized as a noble—albeit the lowest rank of nobility—and this status would grant him economic and social benefits, such as tax exemption. To attain this honor, and to force his local officials in Campanario to recognize it as well, Gonzalez had to prove to a court of officials known as the Sala de Hijosdalgo (Chamber of Hijosdalgo) that he was who he claimed to be. Once recognized as an hidalgo, Gonzalez commissioned a beautifully illustrated manuscript to memorialize his status. The document tells the story of Alvar Gonzalez’s life, genealogy, and lawsuit. Gonzalez’s manuscript, known as a carta ejecutoria de hidalguia (nobility patent), is part of the Newberry Library’s collection. This essay will explain what cartas ejecutorias de hidalguia are and what they can tell us about sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spain.

During the late medieval era, many individuals received the honor of hidalgo status, but with the passage of time, this noble status was not always locally recognized. If a person or family was willing to submit a documented family history to local officials of the Chamber of Hijosdalgo of the Chancellery Court of either Valladolid or Granada, they could sue for formal recognition. Although many tried to do this, few were successful in their lawsuits. If the title of nobleman was officially conferred, the individual or family would often commission luxury copies of their submitted paperwork to be illustrated and bound with the royal seal. These compiled documents became the cartas ejecutorias de hidalguia (nobility patents) that were passed down from one generation to the next. Many families kept these documents for decades or centuries but eventually sold them to book dealers and collectors, who later donated them to a museum or library (like the Newberry).

In contrast with today, in which the question “who am I?” is often personal, in early modern Spain, one’s identity was public. The early modern period in Spain is roughly the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, at the time of the growing Spanish Empire and European Renaissance. The scholar William Childers suggests that when studying early modern Spain, we need to replace the idea that the opposite of a public life is a private life, and instead think of the opposite of public as “secret.” Early modern Spaniards did not have the privilege or expectation of privacy the way we do today, especially because of the looming threat of the Spanish Inquisition whose mission was to root out heresy. In the context of the Spanish Inquisition, heresy meant any belief or opinion contrary to Catholic doctrine. Of course, the authorities could never truly know what someone felt in their heart. The Inquisition was their attempt to “inquire” about these beliefs by watching and questioning individuals and punishing or correcting heretical beliefs and behavior when necessary. The power of secrets, rumor, and reputation could destroy a family’s social standing in this climate. As Childers reminds us, “One powerful clan could obligate another to initiate a costly pleito de hidalguía (nobility lawsuit) in the Chancery at Granada or Valladolid simply by starting a rumor concerning their purity of blood.” If such a thing did occur and a person’s status was cast into doubt, they could sue for recognition at one of the Chancellery Courts in Granada or Valladolid.

Not all families were willing to submit themselves to the scrutiny required to be recognized as an hidalgo, despite believing that an ancestor of theirs was an hidalgo. Francisco Quevedo (1580-1645), one of the most famous early modern poets, wrote a poem that highlights the fear of rumors and tainted reputations that gripped Spain. The poem is known under the title, “Advising a friend, secure in his nobility, not to have his genealogy researched.” In the poem, the narrator advises his friend not to investigate his past: “Don’t tamper with your kin’s long-buried bones; / you’ll find more worms than crests residing there / when newly questioned witnesses tell all.” The poem underscores the fragility of an individual’s reputation in early modern Spain. When the speaker tells his friend not to “tamper with your kin’s long buried bones,” he means that one should not investigate too deeply into their family’s past and genealogy. Like many of Quevedo’s poems, the tone is critical and satiric. The poem implies that the friend is more likely to find evidence of a lack of honor and nobility that would ruin his reputation than evidence of nobility that would improve or even maintain his social station.

Essential Questions:

- Today in the United States, we do not have nobility, but can you think of some steps people take to ascend socially?

- How do you think genealogy and ancestry play a role in your own identity? Have you ever studied your genealogy? If so, how did it affect how you see yourself?

- What difference is there between public and private identity today? What elements define someone’s public identity and their private identity?

Legal Proceedings and the Purchase of Nobility

During the rule of the Catholic Monarchs (Isabel of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon), many individuals were rewarded for their service to the crown with the title of hidalgo (nobleman). The Catholic Monarchs issued hundreds of these titles to reward people for their military and personal service. However, by 1495 the issuing of these privileges slowed. Even though many families were granted this title, there was no guarantee that local governments would recognize the title and allow for the privileges that it entailed, such as tax exemption. The pleitos de hidalguia (nobility lawsuits) were cases in which a person sued for recognition of noble status when it was not recognized by the local government or was for some reason in question. As mentioned above, hidalguía (or “nobility” in English) was the lowest rank of nobility, below caballeros (knights), señores (lords), barones (barons), vizcondes (viscounts), condes (counts), marqueses (marquess), duques (dukes), and principes (princes).

There were far more nobles in Spain than there were in other countries in Europe at the time, and scholars have estimated that the number of hidalgos in Castile made up five to ten percent of the population. This meant that there were over 100,000 hidalgo families in 1541. This was a lot of noblemen, especially since there were only about fifty families in Castile who were señores. In sixteenth-century Spain, people moved from one region to another far more than they ever had before. This made it hard to ensure both that those who were hildalgos were receiving the appropriate treatment in their new place of residence, and that people were not falsifying cartas de hidalguia when they moved to a new city. A family could only prove their status by producing a patent of nobility, or by having witnesses testify on their behalf.

Corruption was also prevalent in the Sala de Hijosdalgo and this affected whose lawsuits were successful and whose were not. For example, some suggested that officials in the chancellery courts could be bribed. Also, people would sometimes forge royal patents, or pay friends and neighbors to testify on their behalf that they were hidalgos. Some scholars of early modern Spain have pointed to the large number of hidalgos as part of the economic problems in Spain, because the more hidalgos there were, the less money the crown could collect in taxes. This put more pressure on the lower class (pecheros) to pay these taxes, thus widening the gap between the upper and lower classes. However, not all scholars agree with this economic argument. The high number of pleitos de hidalguia (nobility lawsuits) suggests that many families had to sue for the privileges of tax exceptions and could imply that a large number of hidalgos were still being taxed by local authorities. Either way, the crown became suspicious of false attempts to seek hidalgo status and the king’s attorney (fiscal real) was required to intervene in all pleitos de hidalguia to protect the king’s interests.

Essential Questions:

- Who pays taxes today and who is exempt from paying taxes? When you hear or read about ‘tax exemption status,’ what comes to mind? Why do you think this status was important to the hidalgos? Why is it important to people today?

- How else do you think the hidalgos might have fought to maintain their social or economic privileges? Do people today use similar techniques?

- Why did Spain have more nobles than other European countries? Besides potential changes in tax revenue, how else do you think the larger number of nobles affected society?

Inside the Book: The Text and Illustrations

If a person was granted noble status after their pleitos de hidalguia, they could choose to have a book commissioned that memorialized their legacy and status. The books were handwritten manuscripts and became known as nobility patents. While each was customized for the family that commissioned it, they followed a formulaic structure. These books were passed on for generations and sometimes more information was added to them in the case of an ongoing or relitigated pleito de hidalguia.

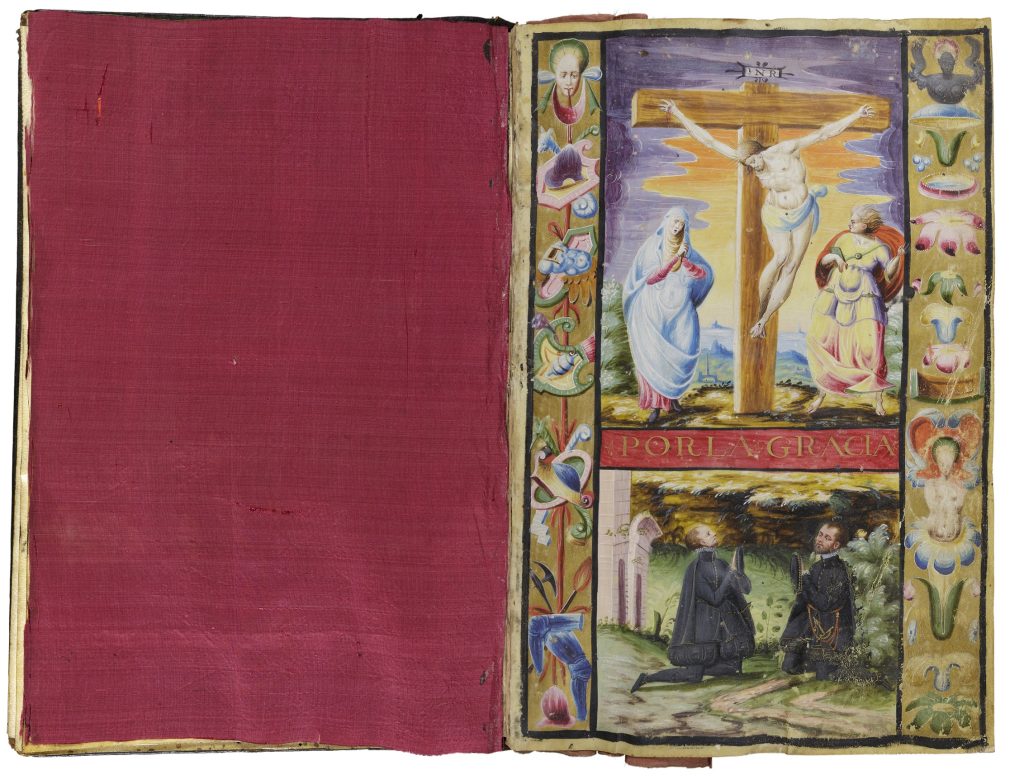

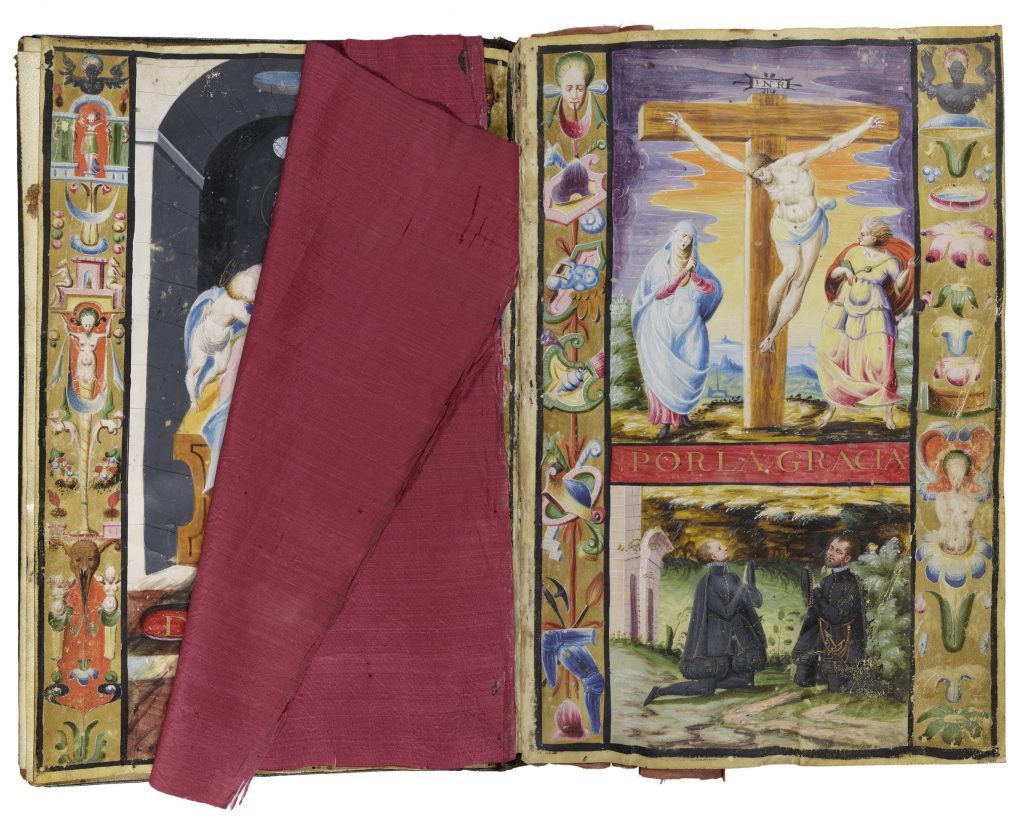

The text and illustrations of the nobility patents demonstrate the factors Spanish society recognized as essential to noble status. Some aspects of a family history that the text and images would highlight are religious devotion, service to the crown, and purity of blood. To show religious devotion, the family would demonstrate their Catholic fervor and reference any relatives who had become clergymen.

Similarly, to show service to the crown, they would mention military or administrative positions they or family members had held that supported the monarch. Finally, blood purity was an important concept in early modern Spanish society. To be able to claim to have ‘pure blood’ a person had to prove that their a family lineage was absent of any Jewish, Muslim, or ‘heretical’ ancestry. For some people, this was hard to prove. If one could not ensure they had purity of blood, they would try to obscure facts about lineage in order to fake it.

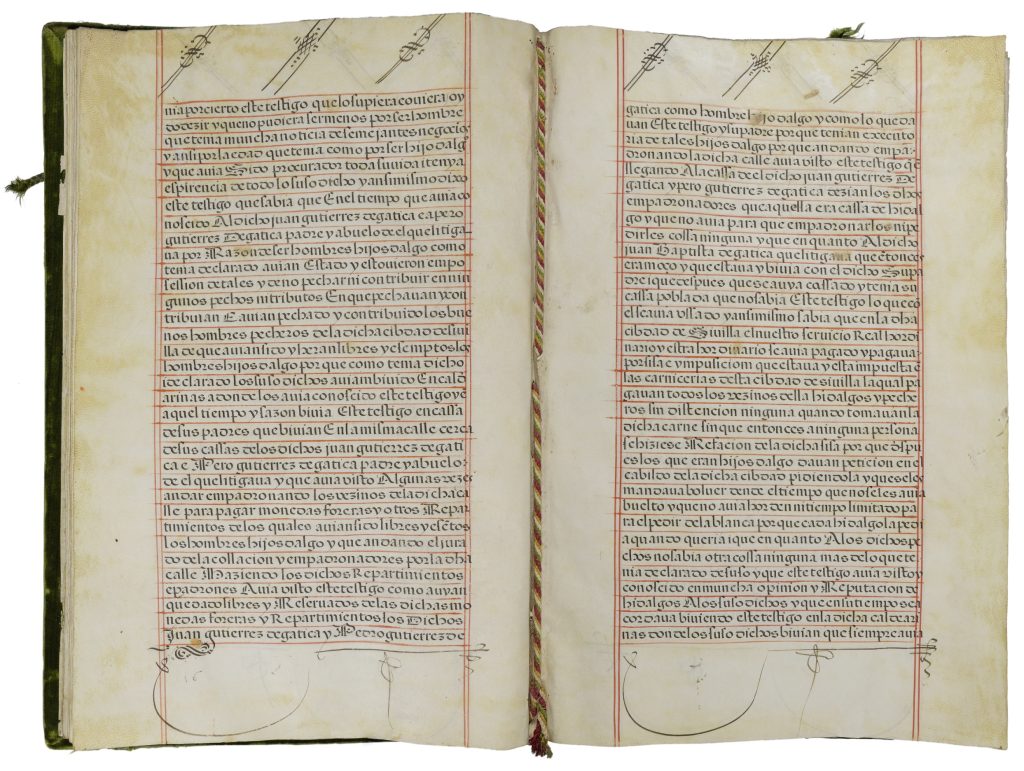

The text of the carta ejecutoria de hidalguia contains the documents that were generated during the judicial process, the names of the parties involved, and the reason for the lawsuit. The text ends with the declaration of the verdict. The court’s final decision was usually issued on paper, or if a person could afford such an expense, they could request a parchment copy. (Parchment is the skin of an animal, such as sheep or goat, that is prepared to become thin and flat so that it can be written on.) These documents were legitimized by the notary symbols, like occasional paper seals and signatures contained within the text.

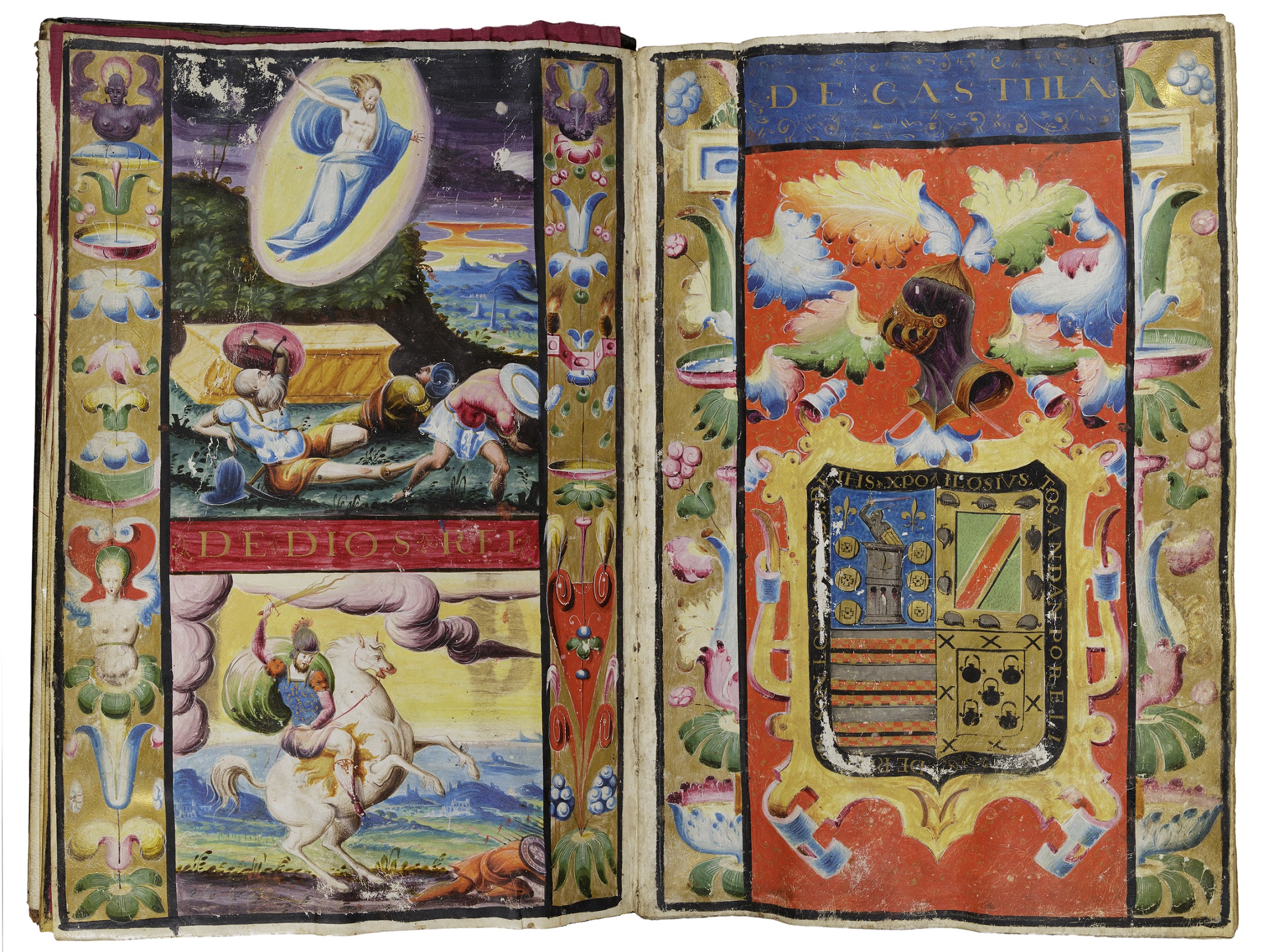

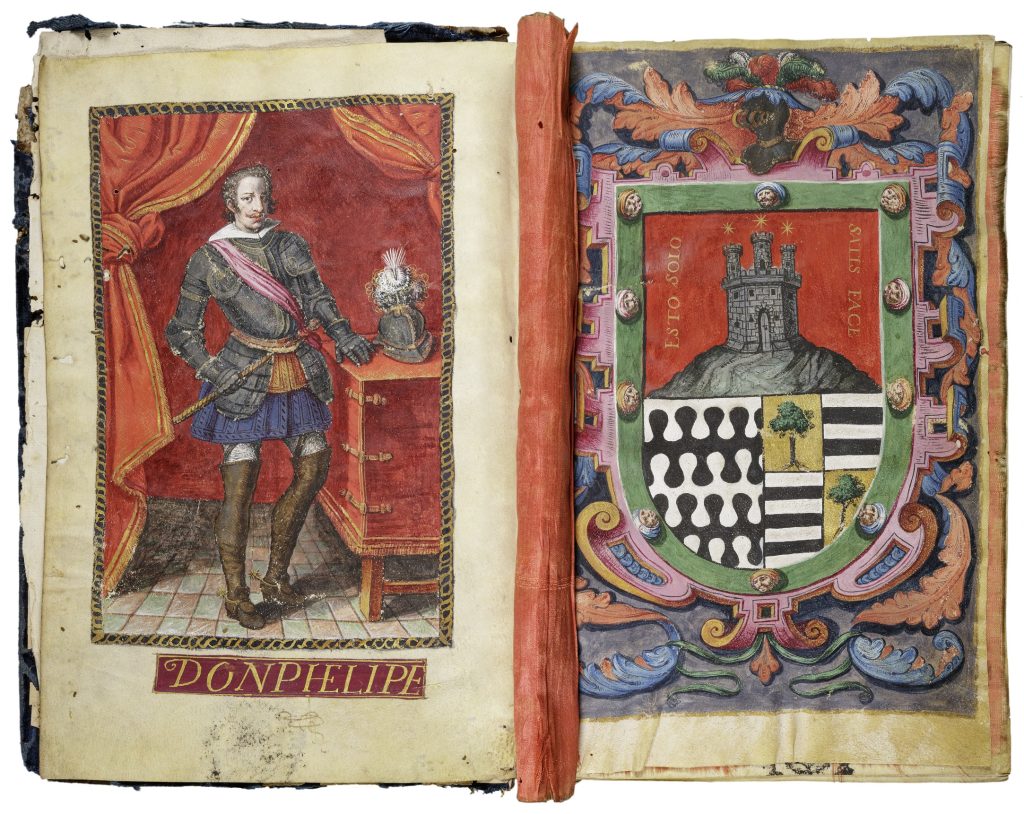

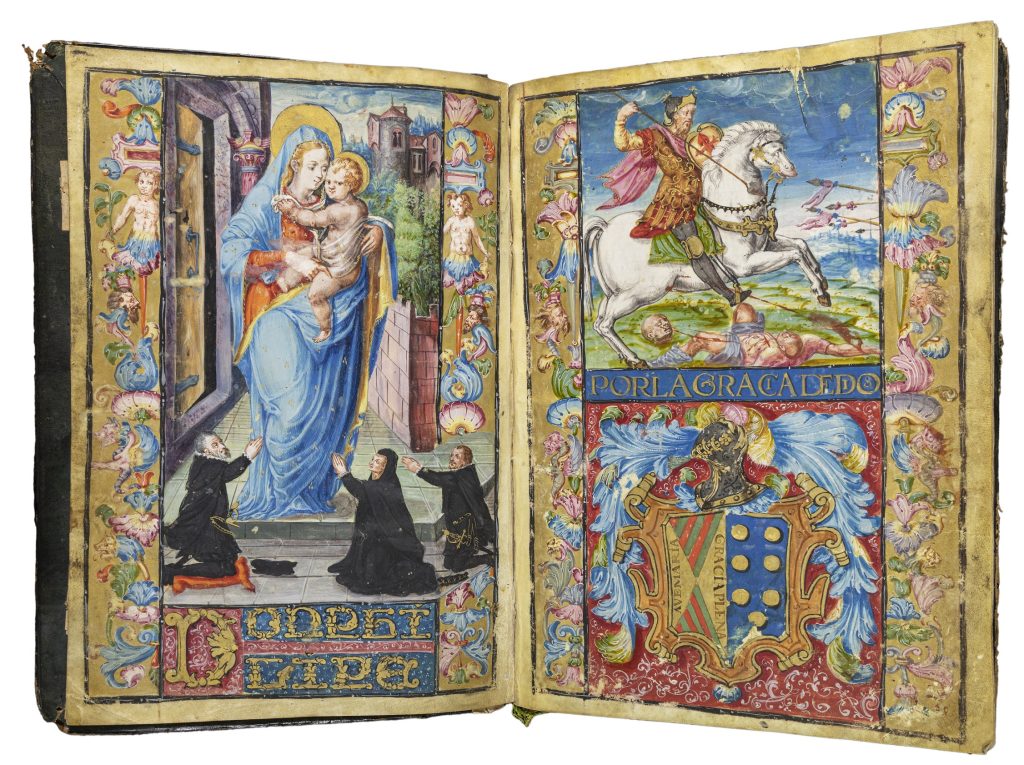

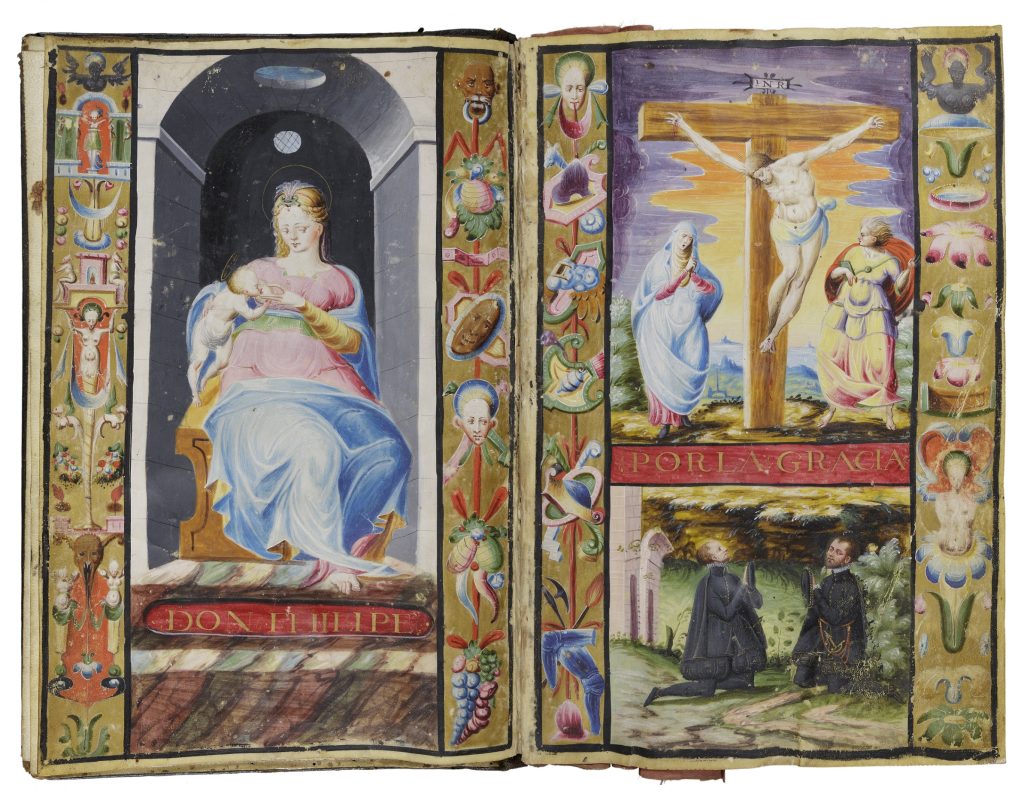

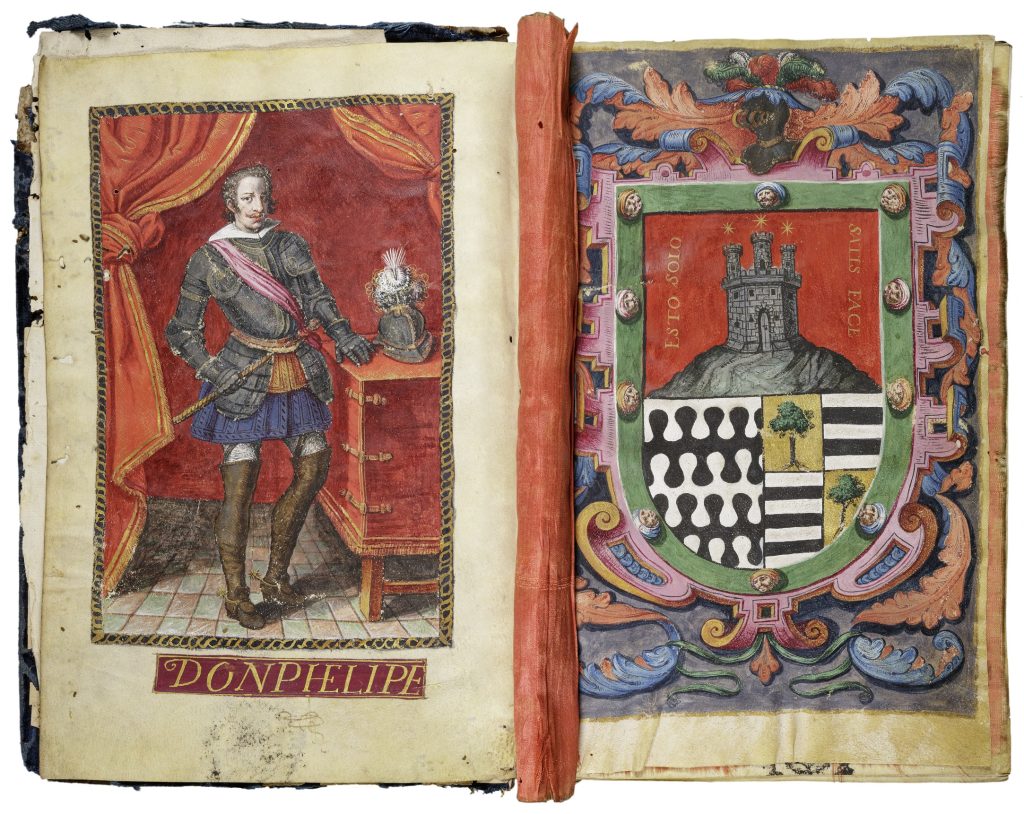

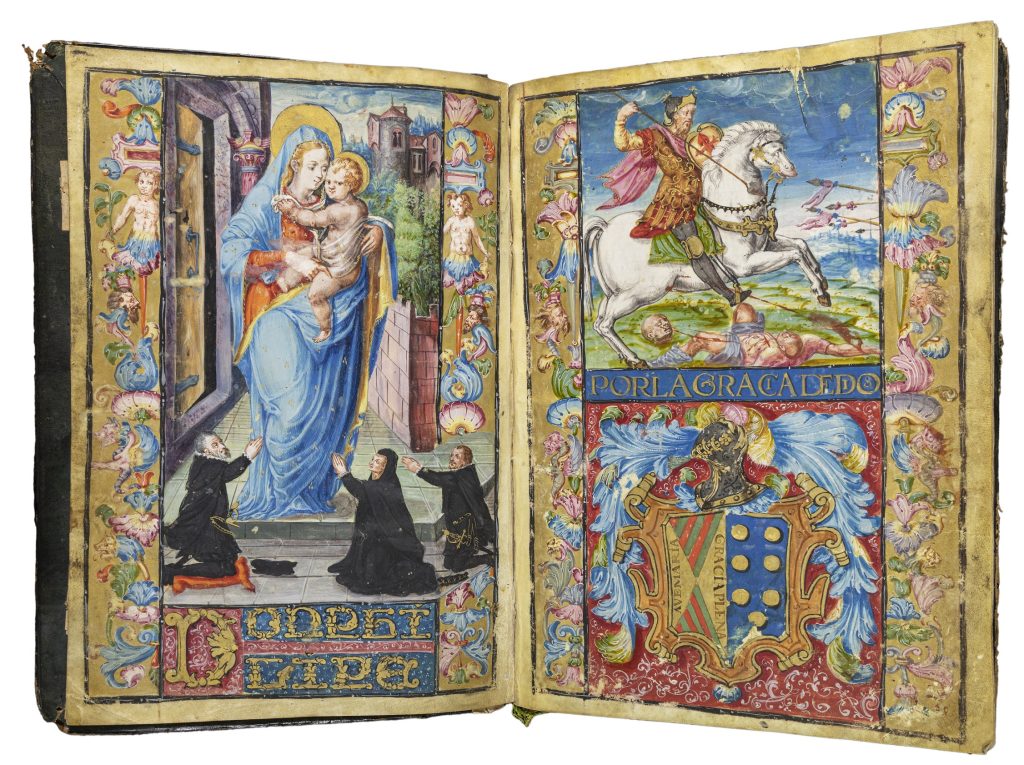

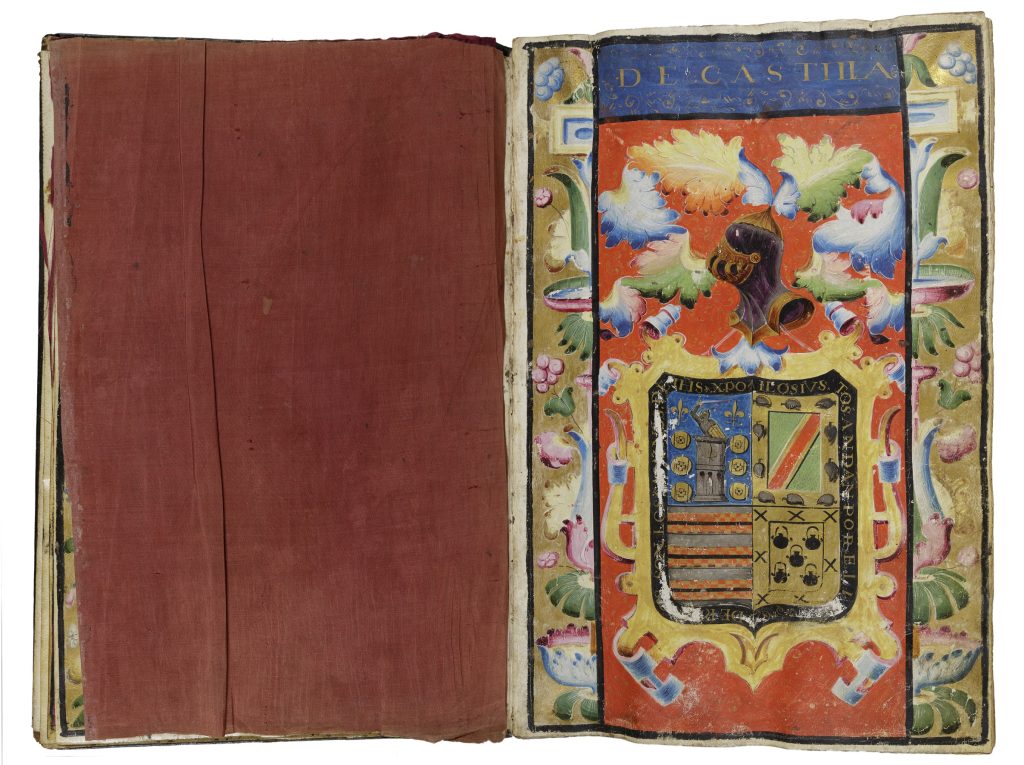

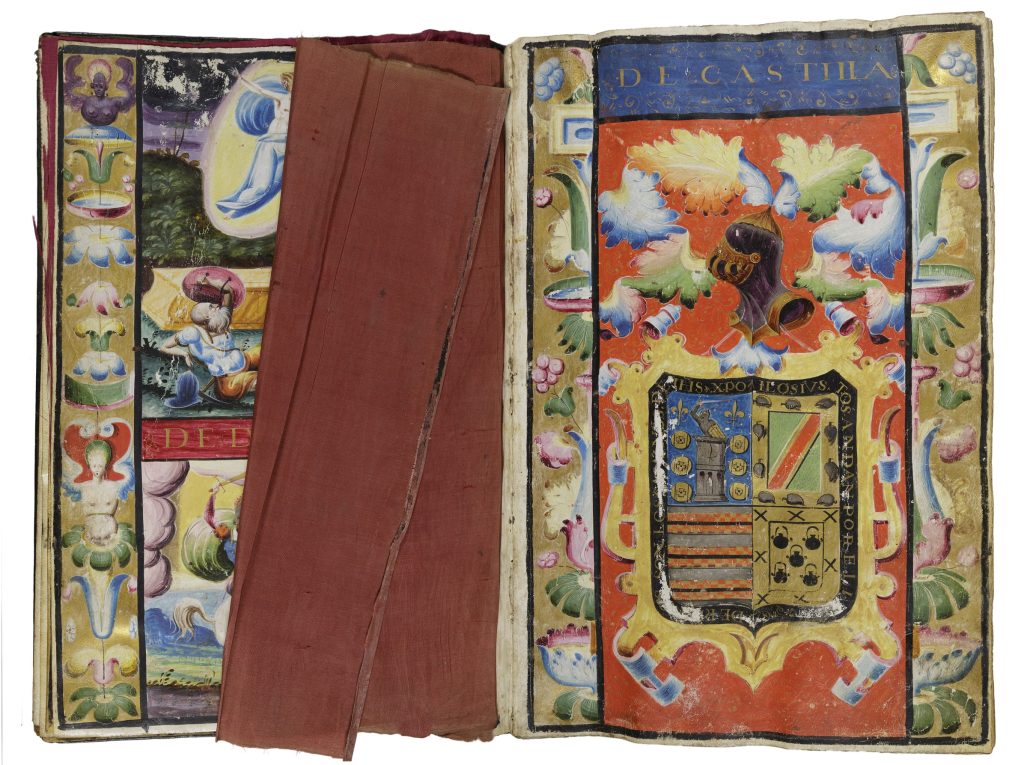

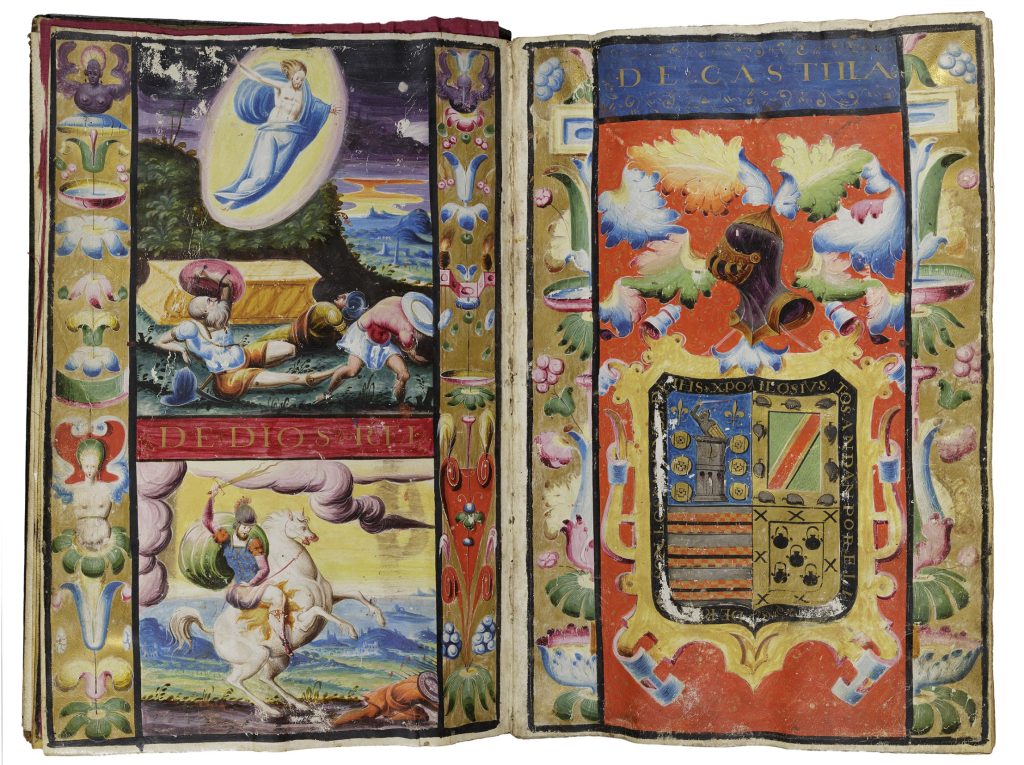

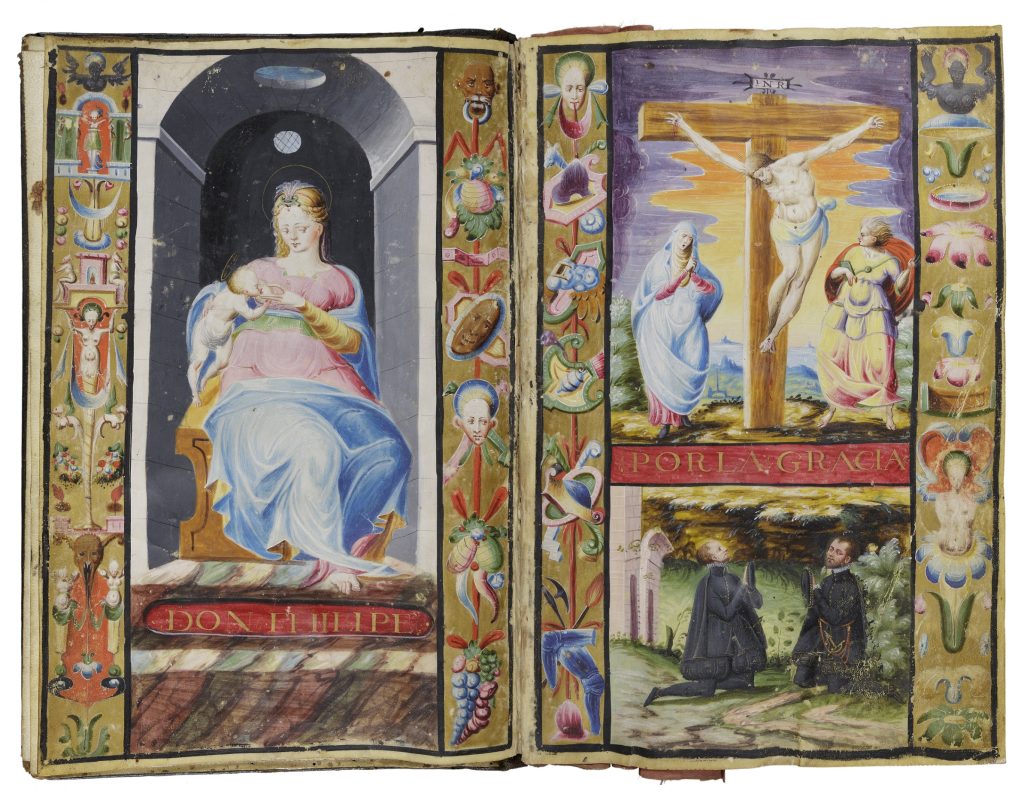

The pages inside of the cartas are full of elegant script and elaborate illustrations. Most cartas include a pair of illuminations in the first two pages, often including images of the Virgin Mary and a family crest, with occasional in-text portrait miniatures and decorative letters. The illuminations often combine religious, monarchical, and genealogical themes, all of which usually support what is being articulated in the text: that the litigant in the case is pious, devoted to the crown, and from an important family.

For example, in the carta above, which belonged to Alvar Gonzalez el Moxo from Campanario, there are two full-page illustrations at the front of the manuscript. The first illustration is a devotional painting of the Virgin of Loreto holding the Christ Child with the much smaller aspiring hidalgos kneeling below. One of the people kneeling below, probably the larger figure on the red pillow, is likely Alvar Gonzalez el Moxo. On the opposite folio (a leaf or page of manuscript), there is an image of Santiago Matamoros, or Saint James, the patron saint of Spain, known as the “Moor-Slayer.” (The term “Moor” was used in medieval and early modern Spain to refer to Muslims.) Between the years 711 and 1492, much of the Iberian Peninsula (the land that we think of today and Spain and Portugal) was conquered and governed by Muslim Caliphates. Throughout much of Spanish history the “Moors” were viewed as the invading army and the enemy. The image depicts Saint James, astride a white horse and dressed in elaborately adorned armor, riding into battle and trampling figures representing the Moorish enemy. This violent iconography, which was common at the time, reflects the dominant Catholic narrative of the warrior saint defeating the alleged Muslim infidels. Below, there is an illustration of the family’s coat of arms. The proximity of these two images is intended to signal the blood purity of the Gonzalez family and their religious fervor. The pages are embellished with gold borders filled with floral imagery which represents the family’s wealth and nobility. As mentioned previously, these illustrations are meant to represent that family’s service to the crown, religious devotion, and purity of blood.

Some of the cartas have colorful silk guards that lie between the illustrated pages to protect the painted images. These silk page protectors add to the sense of splendor of the book. We can imagine that after going through the trouble of a trial to prove one’s nobility, a family would take care to protect the book documenting it. These silk curtains give the cartas a theatrical appearance, a framing element that often appears painted into the illuminations as well. The illustrators used rich colors to adorn the pages and decorated them with metallic gold and silver.

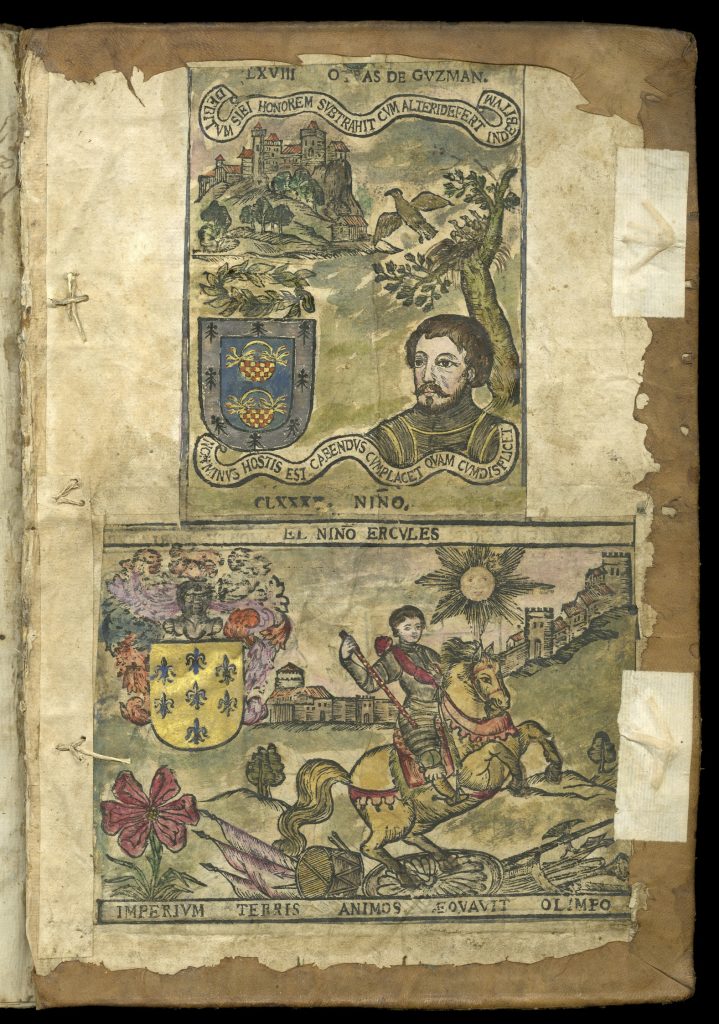

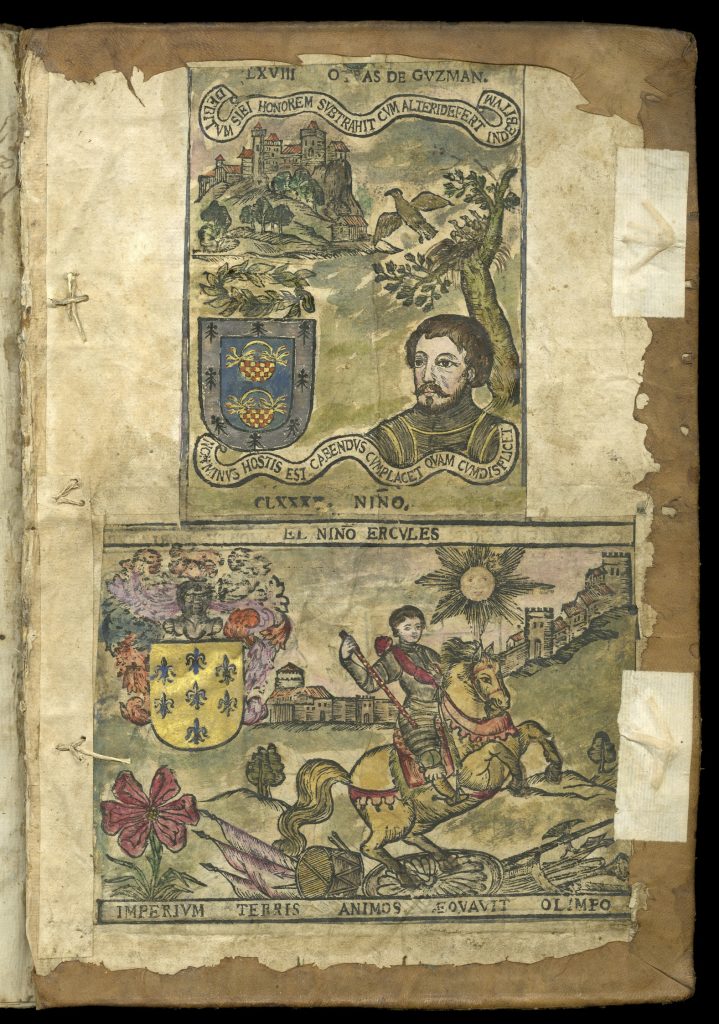

The fashion of creating cartas ejecutorias reached even beyond Spain, and families tried to emulate these trends even when the materials and artisans who made them were not available. For example, one item in the Newberry collection is a carta ejecutoria from Mexico City issued to Miguel de Morales in 1685. The Morales family clearly needed to be creative with how they illustrated their manuscript. Instead of hand painted miniatures on parchment, as is the norm with early cartas created in Spain, this carta has colored woodcuts featuring the family crests pasted inside the front and back boards of the binding, and a hand-colored engraving of Ferdinando III included near the front of the book. These woodcuts would have been more readily available in the Americas than traditionally trained illustrators, and colored woodcuts would have been much affordable than having an illustrator paint miniatures.

Essential Questions:

- What makes a book or object commemorative? If you had to make a book to commemorate your history, or your family’s history, what text and images would you include? What materials would you use, and what would it look like?

- What makes a book valuable?

- We do not have cartas in the United States today, but what are some things that people display to show they belong to a certain family or community?

The Outside of the Book: Seals, Bindings, and Cords

While each carta has its own decorations and adornments to communicate unique characteristics of its owners, there are some values that are consistent throughout all these books. All the families try to communicate that they are deserving of recognition, that they are loyal to the Spanish monarchy, and finally that they are devout Catholics. This was done not only through the illustration and text inside the book; even the covers, binding, and external elements of the book were carefully considered. In this section we will talk about the outside of the books and perhaps most importantly, the lead seals that were given to each noble family and attached to the books with colorfully braided cords.

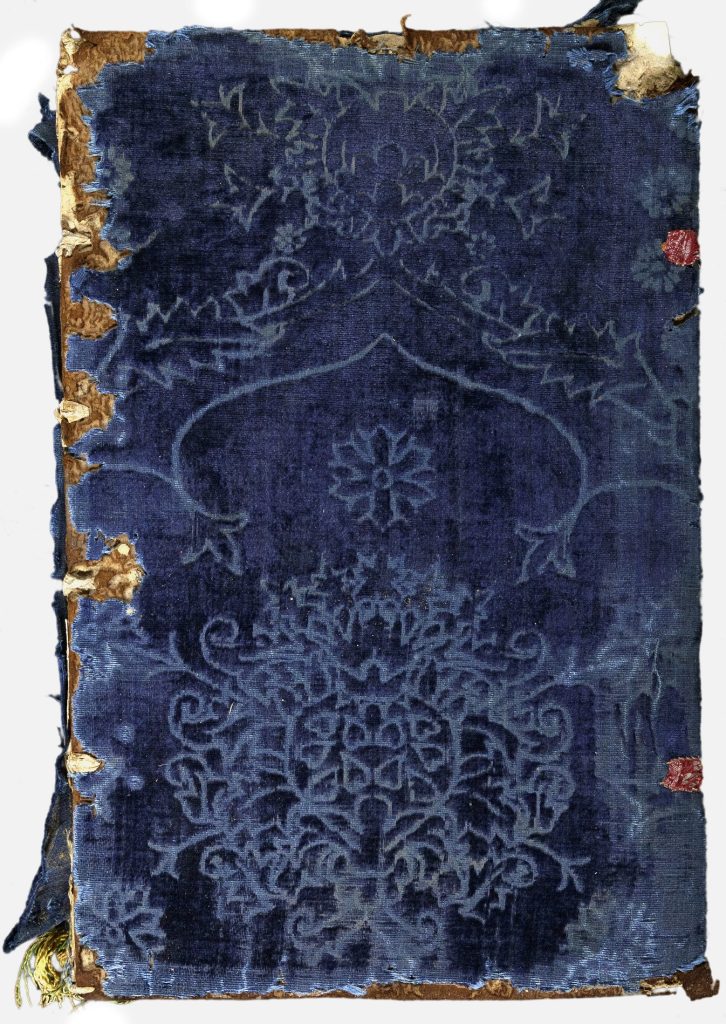

Some of these manuscripts are as many as four hundred years old, and yet many of them still have their original covers and bindings. Bookbinding in Spain has Islamic and North African origins. This history makes it different from Italian bookbinding, which was influenced by Byzantine binders. The original covers of the cartas are often made from colored velvet or gilt leather. Below are images of two covers of cartas in the Newberry Library collection. The first is an example of the carta with a brown leather cover with gilt emblems. This book was made after a patent was granted to Rodrigo de Rueda from Carmona Seville in 1568. The cover has decorative gold emblems on it in the shapes of lions and skulls and crossbones. In the next example you can see the dark blue velvet cover of a carta granted to Miguel de la Peña from Soria, in the north of Spain, in the mid seventeenth century. These two types of covers, gilt leather and colored velvet, are common for the cartas ejecutorias.

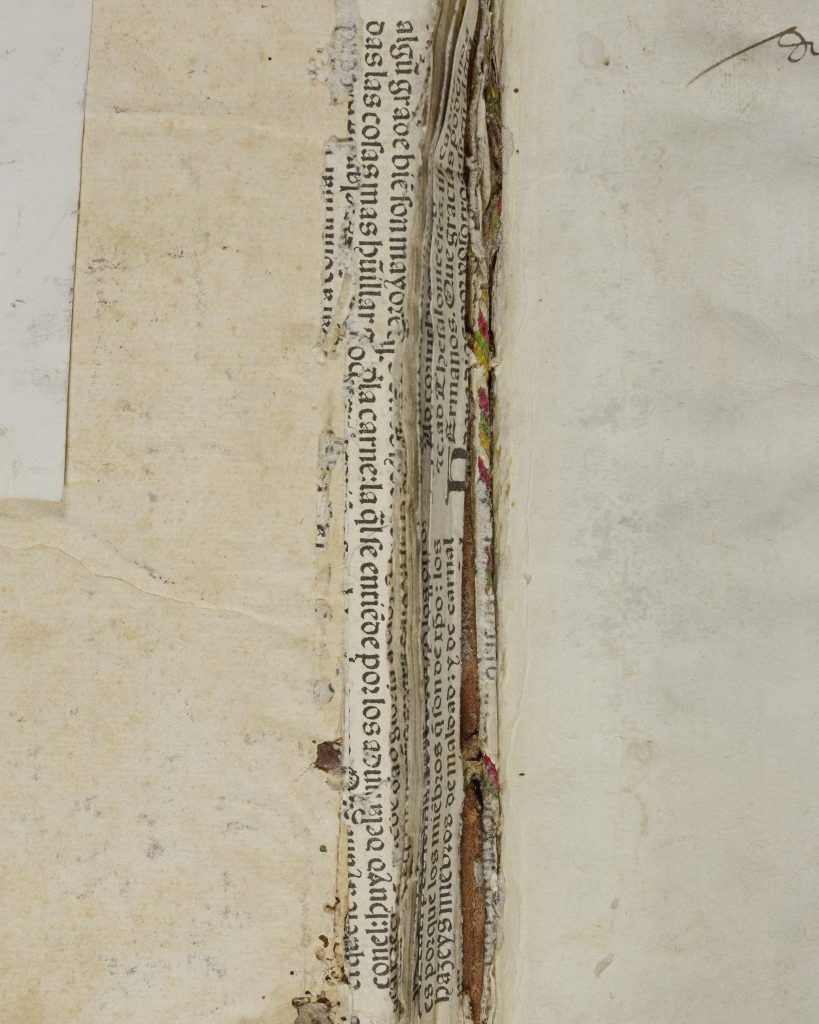

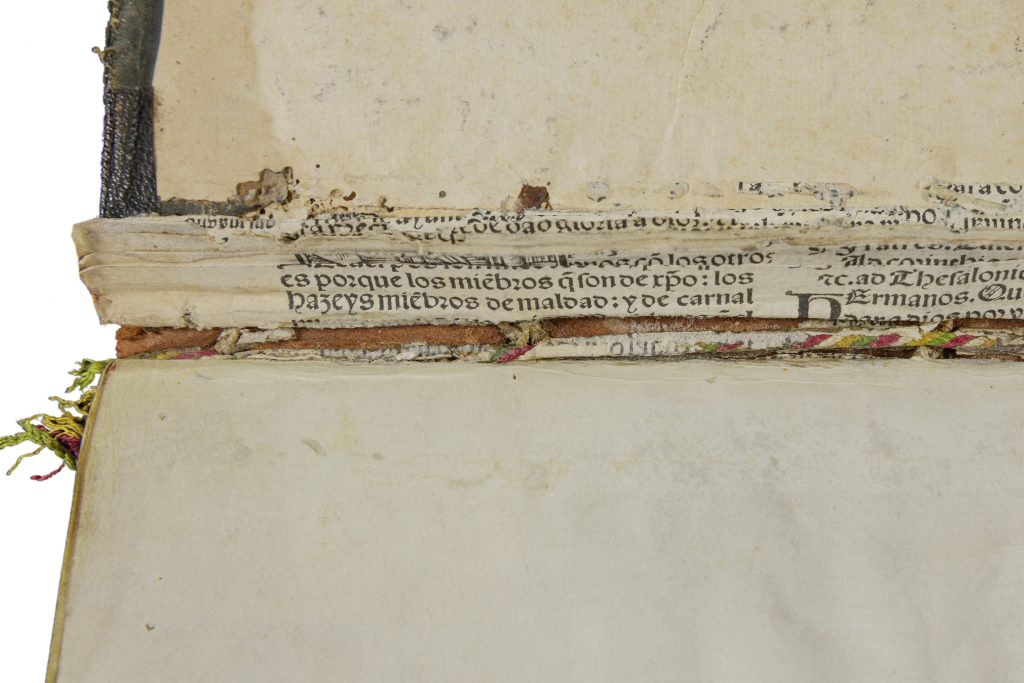

These manuscripts also contain some interesting surprises. For example, bookbinders in the early modern period reused damaged and misprinted paper as binding waste. In other words, fragments from discarded books were used to bind other books. These scraps can give us hints about what other books the binder may have been working on and sometimes can reveal new books that have not been saved in any other form. For example, in these images you will see some binding waste that appears to be from an edition of a book of sermons.

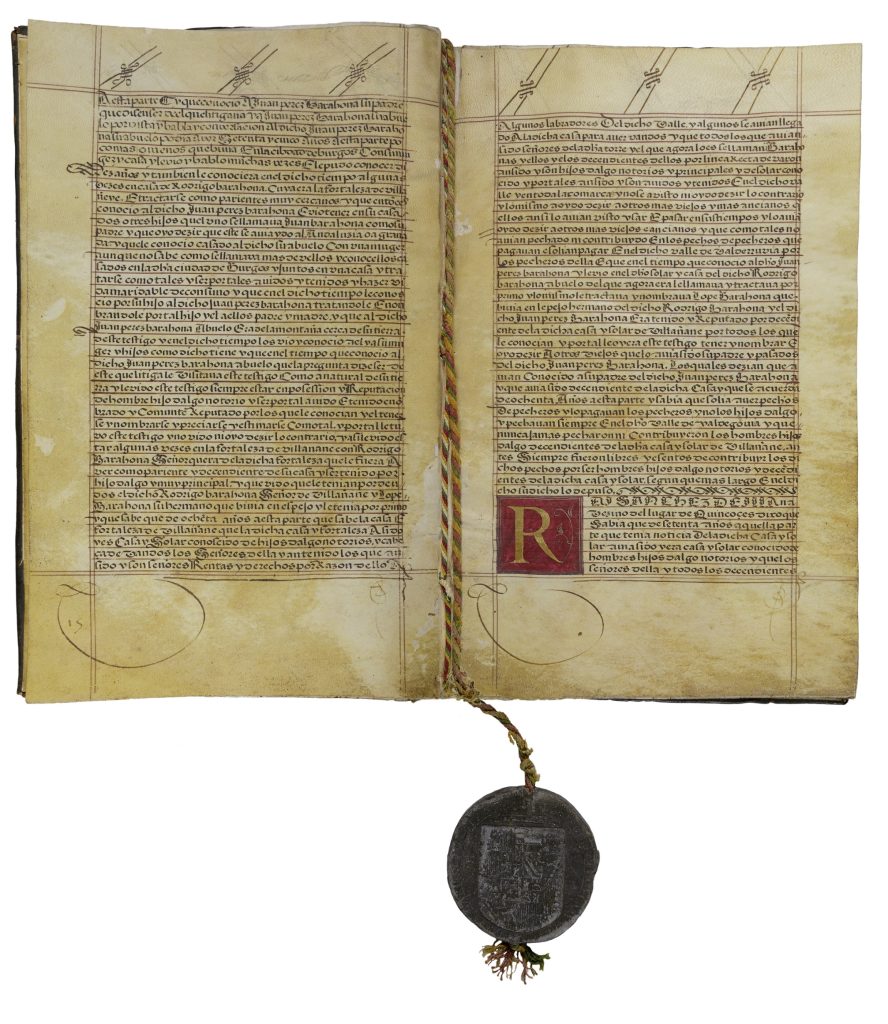

Finally, perhaps the most important part of these cartas ejecutorias was the official seal confirming their authenticity. As you can see in the example of Miguel de la Peña’s book, there is a cord hanging from the bottom left corner. This cord of braided silk threads would have been used to attach the lead seal. Each book has its own cords with different colored silk strands that are woven between the pages and through the spine of the book.

Then the cord was embedded in lead disks, which bore the pendent seals of the king. The sealed manuscript was a means to authenticate the noble status of the family. While only a few of the cartas de hidalguia in the Newberry’s collection have seals that are still attached, from these remaining examples we can see that the seals were substantial in size; these have a diameter of about four inches.

Essential Questions:

- If we were to judge these books by their covers, what would they tell us about their owners?

- Why are covers of books important, what purpose did they serve for the cartas, and what purpose do they serve today? How are those purposes similar or different?

- Many people, scribes, artists, bookbinders, worked to make these books. Have you ever collaborated with friends to make a graphic novel, comic book, zine, or another kind of document or text? What was that process like?

About the Author

Elizabeth A. Neary is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her dissertation, “Significant Others: Mixed Marriage in Early Modern Spain,” examines marriage between Moriscos and Old Christians as represented in both literary and archival sources. Her research engages with themes of religious and national identities and minority groups in early modern Spain. Elizabeth is currently the Project Assistant for the Institute for Research in the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the Charles Montgomery Gray Fellow at the Newberry Library.

Written with the assistance of Suzanne Karr Schmidt (PhD, Yale), George Amos Poole III Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at Chicago’s Newberry Library. A historian of early modern art, books, prints, and science, her monograph, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance, appeared in 2018. She has published widely on the topic of hybridity and materiality in print. Her next project is the playful Newberry exhibition, Pop-Up Books Through the Ages (March 21-July 15, 2023). Accompanied by a Collection Essay, it examines this overlooked artform from the medieval to the modern era. Her previous prizewinning exhibitions include her co-curated 2020 Newberry exhibition Renaissance Invention: Stradanus’s Nova Reperta, and her 2011 Art Institute of Chicago exhibition Altered and Adorned: Using Renaissance Prints in Daily Life. She has also worked on Golden Age Spain, most notably in a catalogue raisonné of the artist Juan de Pareja, best known as the manumitted slave to Diego Velázquez.

Further Reading

Childers, William. “The Baroque Public Sphere.” In David Castillo and Massimo Lollini, eds. Reason and Its Others: Italy, Spain, and the New World. Vanderbilt: University of Vanderbilt Press, 2006, pp. 165-85.

Crawford, Michael J. The Fight for Status and Privilege in Late Medieval and Early Modern Castile, 1465-1598. Penn State UP, 2014.

Kagan, Richard L. Lawsuits and Litigants in Castile, 1500-1700. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1981.

Mercado-Oliveras, Verónica, Alcántara-García, J. “Cartas Ejecutorias de Hidalguía (executory certificates of nobility): a survey in materials analysis, legal, and aesthetic contexts—two case studies.” Heritage Science 11, 6 (2023).

Penney, Clara Luisa. An Album of Selected Bookbindings. New York: Hispanic Society of America, 1996.

Ruiz García, Elisa. “La carta ejecutoria de hidalguía un espacio gráfico privilegiado.” La España medieval, no. Extra 1, 2006, pp. 251-276.