This Collection Essay and the accompanying classroom activity were produced through a generous annual fellowship for digital education on American Women’s History or Early American History funded by the Chicago Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. 2023.

Introduction

The late nineteenth century has often been called “The Gilded Age” because, for a very small part of the population, it was a time of great prosperity and huge wealth. The country’s corporate giants, such as J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and John D. Rockefeller, made unheard of profits in an economy without regulation and with generous subsidies from government on all levels.

The catch words for this time were ”growth” and ”prosperity,” and there was a vision of the American city that reflected those goals. It was embodied in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which exhibited marvels of technology and a new aesthetic.

This, surely, was what the words “American City” would come to mean—a place of beauty and prosperity beyond anything the world had seen.

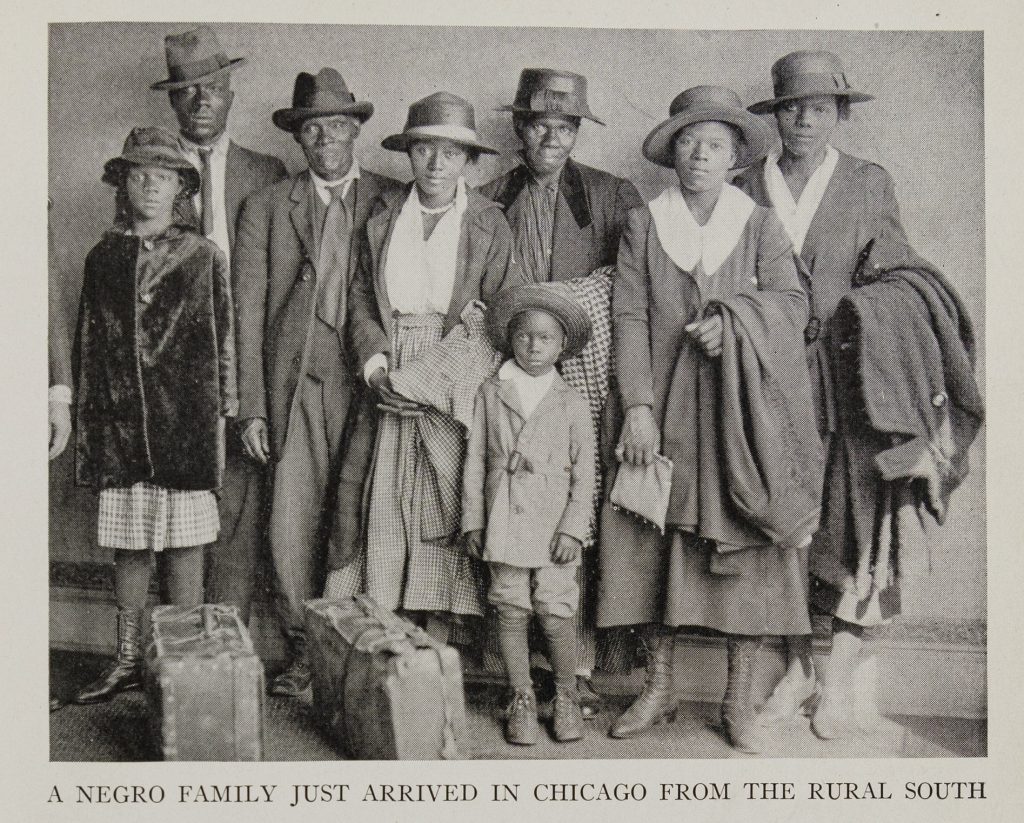

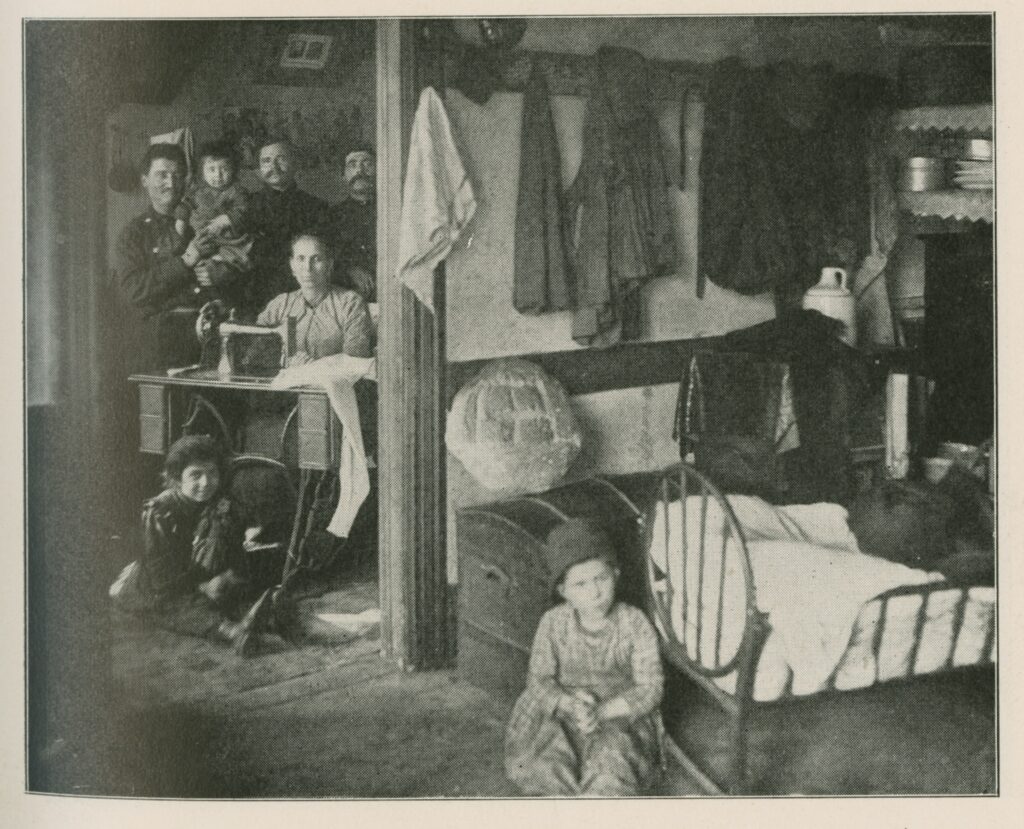

At the same time, however, the combined force of industrialization and urbanization–bringing a huge wave of immigrants from Europe and Black migrants from the American South–came very close to destroying American cities. Millions, frequently more than fifty percent of a city’s population, lived in crowded tenements without plumbing. The pollution of coal-burning heating and power plants combined with open sewers and little to no garbage collection to raise mortality rates and lower life expectancy. Child labor was rampant. And men in government and business continued to focus on growth and progress.

Women, on the other hand, stepped forward to provide immediate social services that saved lives and then to work for reforms that would eventually save the cities themselves. Many of those women, as well as their accomplishments, are familiar to readers and students of history, but their impact is almost universally underestimated. And many others, especially Black women, have scarcely been recognized at all. This project, which was inspired by scholar Daphne Spain’s groundbreaking book How Women Saved the City and Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn’s equally important Black Neighbors, is a way of disseminating information from the Newberry Library collections in order to increase our knowledge of these remarkable women.

Essential Questions:

- What were the motivations of the various people and groups represented in the cities of this era, including businessmen, government officials, settlement house workers, immigrants, and others?

- Why are the last two decades of the nineteenth century still called “the Gilded Age”? What would be a more accurate name for that time period?

- What actions and achievements of women and women’s groups helped to save American cities?

Conditions in the Cities

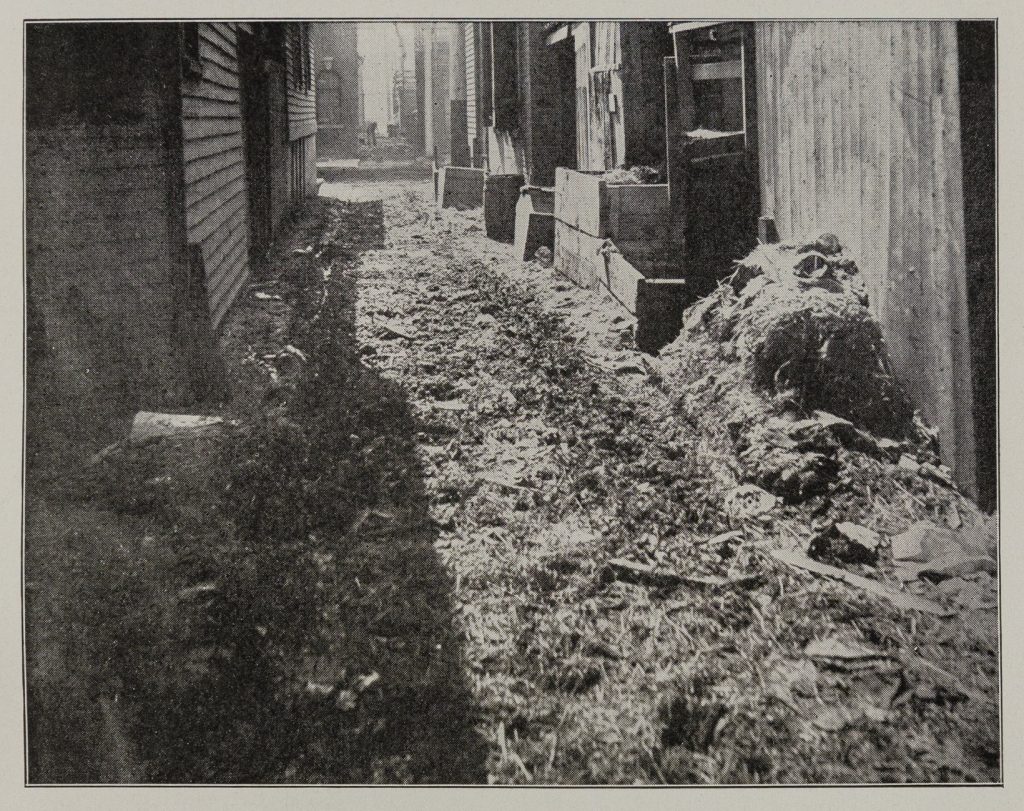

“There is no more important test of the tenement-house conditions than the amount of space covered by buildings. Where there is overcrowding of houses upon lots and blocks there arise all of the most dangerous results of bringing together, in the artificial surroundings of large cities, vast populations. Close and often indecent crowding, natural accumulation of filth, insufficient provision for light and ventilation, lack of yard and breathing-spaces, and a high tax upon the health and life of the people are a few of the results which inevitably accompany crowding of houses upon ground space.”

Robert Hunter, in Tenement Conditions in Chicago, published by City Homes Association in 1901.

Too many people came to Chicago and other cities in the United States in too short a time, and the cities couldn’t—or didn’t—handle it. The population of Chicago doubled between 1880 and 1890 and then again between 1890 and 1910. By 1890, seventy-nine percent of Chicagoans were immigrants. Most of them came to find work in the thriving industries of America. Then, businesses that were losing white workers to the military in World War I encouraged the Great Migration of African Americans from the South. That added hundreds of thousands of people, more than 225,000 in Chicago alone before the beginning of the Great Depression. That was still a small number, compared to the white immigrant influx, but segregation forced this wave of new residents into severely limited neighborhoods, making their living conditions at least as bad, and often worse.

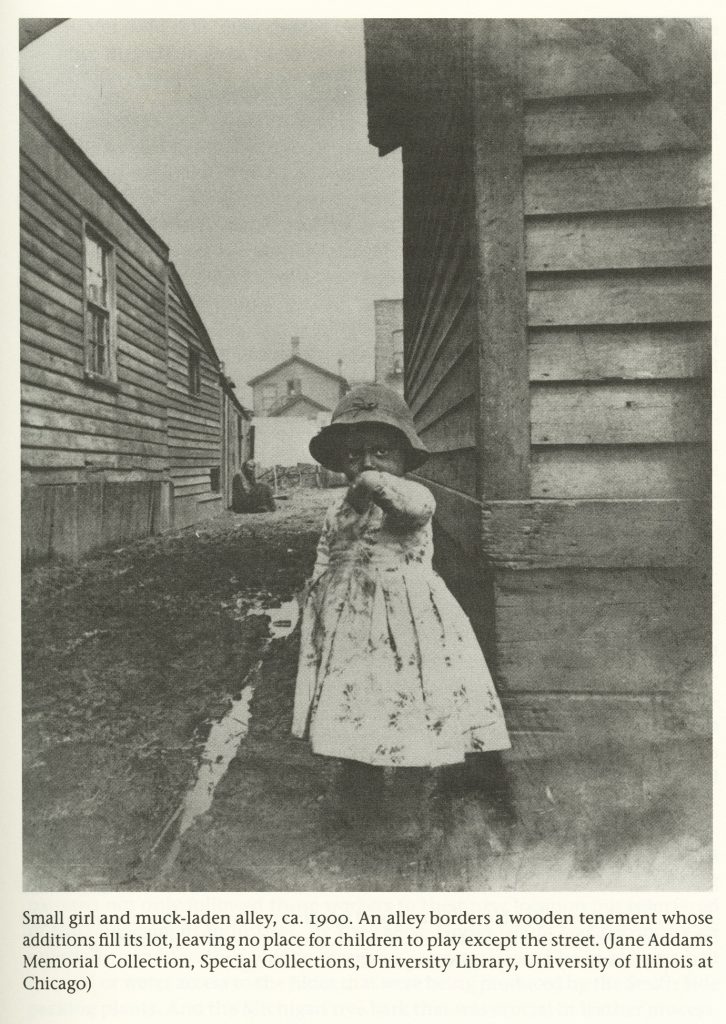

Attempts to house all these people were almost exclusively profit-driven. Tenement owners built on every possible square foot of their land, eliminating green space and reducing ventilation to dangerous levels. Since business was unregulated and unions almost nonexistent, the incomes of newcomers were extremely low. The rents, on the other hand, were high. If a family’s entire income, including wages earned by the children of the family, is five dollars a week or less, and a three-room apartment on the third floor of a tenement is $10 a month, there will inevitably be more than one family living in that apartment. Often, an entire family lived in one room. In addition to overcrowding, there was the issue of sanitation. Tenements did not have running water, so tenants had to carry water from the street level to their apartments for washing themselves, their clothes, their dishes and their rooms, making basic hygiene virtually impossible. According to Spain, “[C]ity residents also had to worry about filthy water. Cholera was a constant threat, and just breathing could be an unpleasant experience for those who survived epidemics. About one-half of the houses had water closets that drained into sewers, and that water flowed unrestricted into rivers and harbors. Thousands of cattle, sheep, and hogs were shipped out of ports each year. All that manure had to go somewhere, as did the offal (organic refuse known as swill) from dwellings.”

Under these conditions, understandably, many people died of disease. Infant mortality was also extremely high. According to historian Thomas Lee Philpott, “Children were the chief victims of the slum. In some tenement wards, in some years, more than 60 percent of total deaths were among children under five years old. And this figure is on the low side, because the Health Department did not count in the mortality schedules the stillborn babies and the infants who died within twenty-four hours of birth. The chances of a child born in the tenements to survive three years were probably less than fifty-fifty.”

The cities were clearly in crisis.

Questions to Consider:

- Why did immigrants come to the cities of the United States in the late nineteenth century? What do you think they expected to find?

- What problems would an immigrant have adjusting to life in a new country?

- Why did African Americans come to Northern cities in the early years of the twentieth century? What do you think they expected to find?

The Women

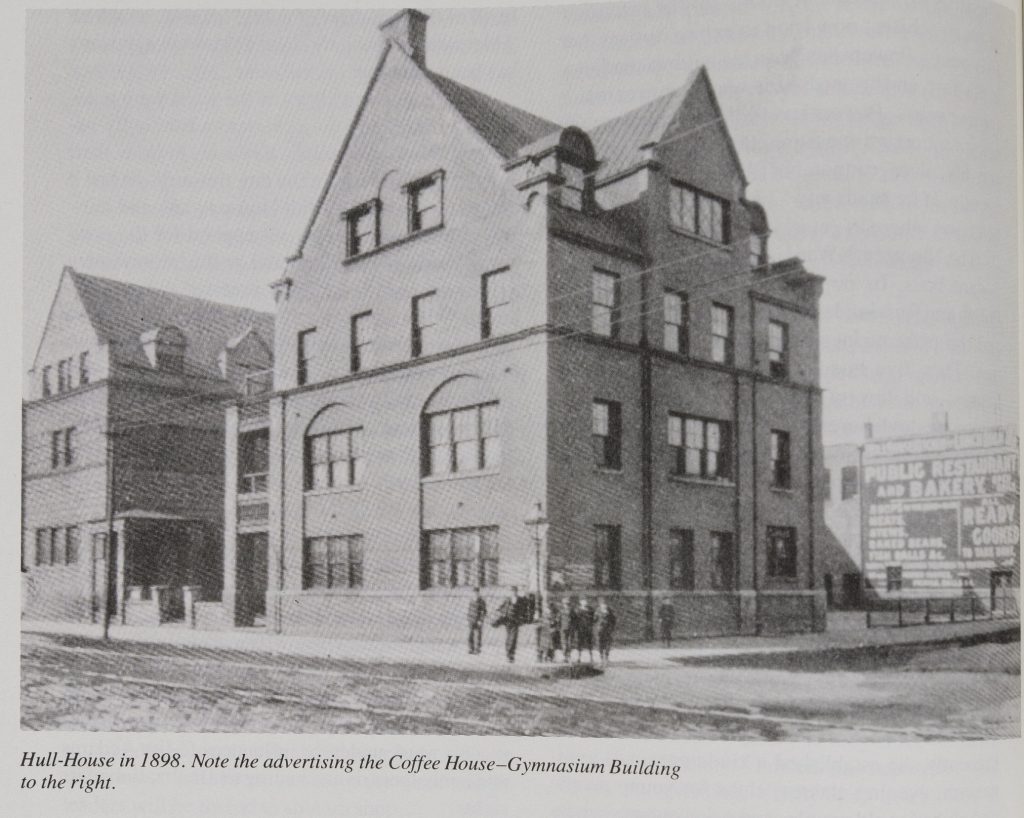

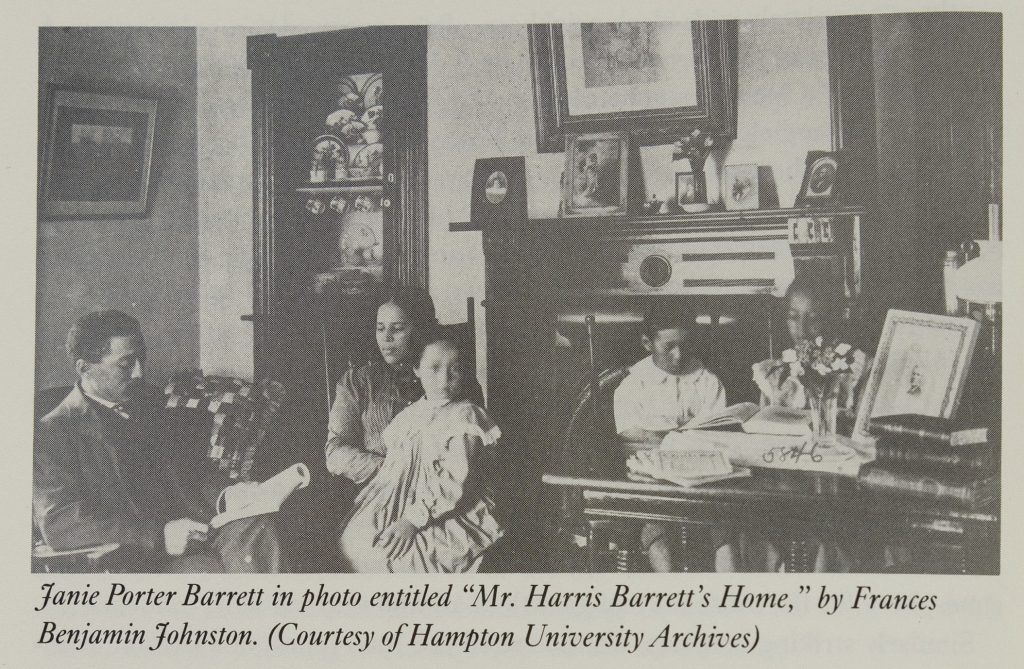

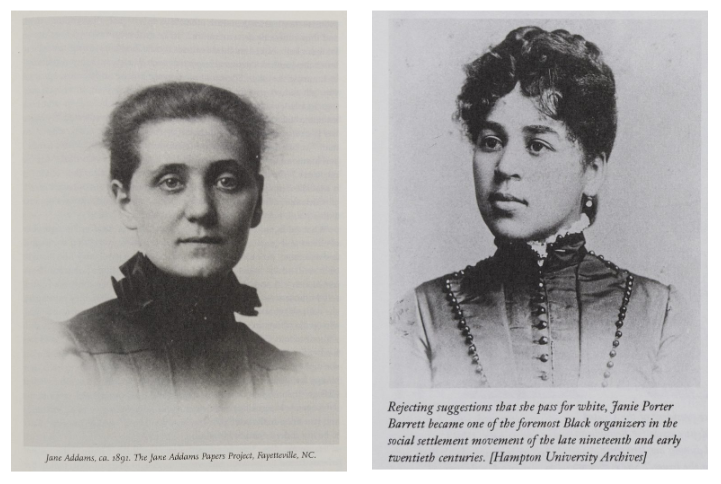

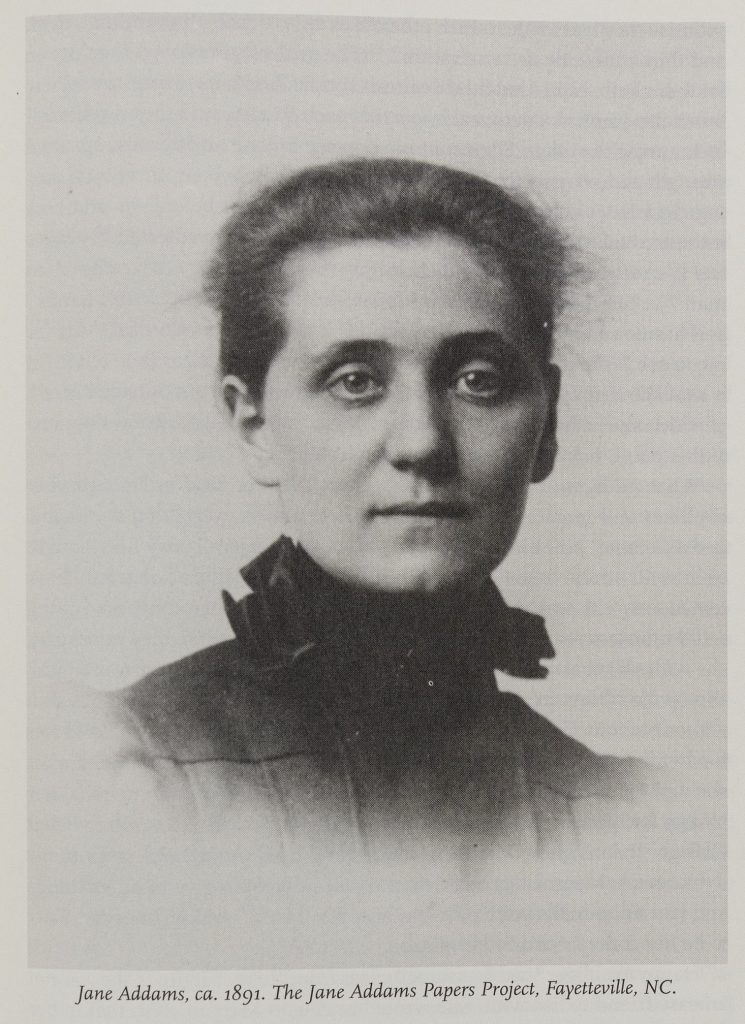

The woman on the left, Jane Addams, is justifiably one of the most famous and admired women in American history. In 1890, she and Ellen Gates Starr opened Chicago’s Hull-House, the first and best known of the settlement houses created by women during what came to be known as the Progressive Era. The woman on the right is Janie Porter Barrett, a well-known figure to students of Black women’s history. She founded the Locust Street Settlement House in Hampton, Virginia, a year later. It was the first settlement house in Virginia and is generally known as the first settlement house for African Americans in the United States.

Looking at these women, it would be difficult to guess how strikingly different their paths were to this same life’s work. And the differences were emblematic of the different ways in which white women and Black women generally prepared for and approached the mission.

Jane Addams was born into a prosperous family in northern Illinois. Because of childhood ill health, she spent a great deal of time reading. She went to college at Rockford Female Seminary and was encouraged by reading Leo Tolstoy and John Stuart Mill, among others, to form a dream of escaping the bonds of conventional womanhood and doing something to help the poor. After having to give up her ambition to study medicine, again because of health, she heard about Toynbee Hall in London, the first settlement house. Inheriting a very large sum, about $1.4 million in today’s money, she persuaded her friend Ellen Starr Gates to go with her to Chicago, where they rented a run-down mansion in a poor, immigrant neighborhood and opened Hull-House.

Addams’s motivations were shared by many white women from affluent families. They chose to work in what Spain calls “redemptive spaces” for many of these reasons:

- They wanted to do good.

- They wanted to use their education doing meaningful work, even though most professions were closed to them.

- They wanted to escape the conventions and limitations of middle-class marriage and family.

- They wanted to share a cultural and social community with other women who had similar interests.

These women were rebelling against the “cult of ‘true womanhood,’” which demanded that women limit themselves to the domestic sphere, be utterly pure in body and in heart, and rise spiritually above their husbands and male society. According to Doris Daniel, biographer of settlement house activist Vida Scudder, one of the founders of the College Settlement House, “To Scudder, the new life permitted a sharing of mind and heart with all people, an escape from the prison of class to a different life that was closer to reality. Most of all, it was a chance to see life at first hand. Though she was one of its founders, Scudder had reservations about what settlements could accomplish for the poor, but she was convinced of their value as a vehicle of enlightenment for women. Another settlement house woman told Ramsay MacDonald, future prime minister of England, that she was part of ‘the revolt of the daughters . . . the revolt against a conventional existence’ and the life that ‘the majority of well-to-do American women have to live.’”

For African American women like Janie Porter Barrett, both the path and the motivations were different, and so, frequently, were the “redemptive spaces” they created. They were not motivated by the desire to break the true womanhood mold. In fact, unlike white settlement house workers, most Black women who served their communities were married and had families.

Janie Porter was born in Georgia, the daughter of a formerly enslaved domestic servant in a household headed by a white woman. Janie’s father is unknown, although it is believed that he was white. The child was allowed to join the white children of the family at their lessons and, when she was fifteen, her mother’s employer tried to persuade Janie to pass for white in order to attend a Northern school. Julia Porter insisted that her daughter go to the historically Black Hampton Institute.

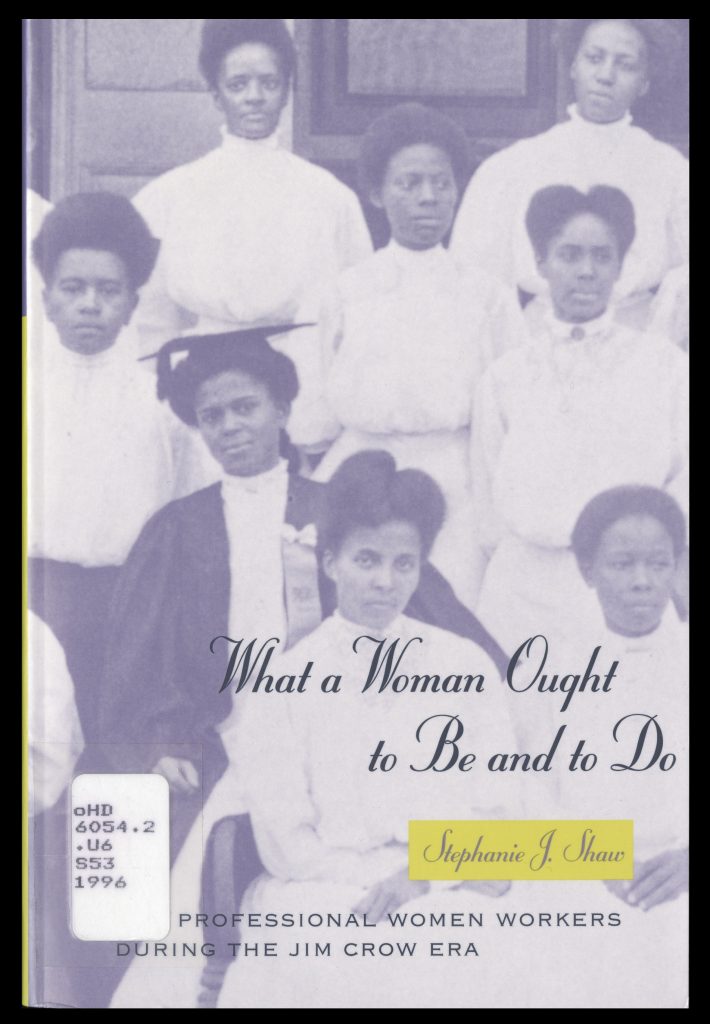

According to Stephanie J. Shaw, author of What a Woman Ought to Be and to Do, young Janie Porter had at first been “unprepared for the intense socialization process that pushed students to commit their lives to serving the black community. Janie quickly tired of being drilled by Hampton faculty and administrators on ‘her duties to her race.’ And she, at first, endured the weekday indoctrination by looking forward to Sunday, because, she said, ‘On Sundays, I didn’t have to do a single thing for my race.’”

Janie Porter had just encountered the Black counterpart to the white “true womanhood”: “noble womanhood.” It was just as strict in its own way, but very different. According to Shaw, the white ideal was not an option for most Black women.

Whether or not parents preferred to see their daughters enjoy lives of leisure or at least lives free of wage-earning duties, they understood that the economic circumstances of black Americans made it unrealistic to assume that one’s child, because she was female, would escape those responsibilities. Black women’s incomes were often critical to the family economy. Parents also knew that without formal education their daughters would have few alternatives to working as domestic or agricultural laborers. The economic and sexual exploitation of black women in these occupations was well known to them, so to ensure that that would not be the lot of their daughters, those mothers and fathers who could do so provided their daughters with as much education as possible — sometimes at great sacrifice. Parents deliberately encouraged the pursuit of courses of study that would lead to higher occupations, and they pushed the children to be self-confident, independent high achievers. These parents were neither unrealistic nor irresponsible in rearing their daughters in this way. Nor had they misread society’s cues about the social and economic options available to black women. They simply insisted upon distinguishing between what their daughters were capable of doing and what they might be allowed or expected to do.

There was a price for education, though. Black women were expected, with all the moral force that Janie Porter had encountered at Hampton, to use their education for the betterment and elevation of the race. It was a long tradition, reaching back as far as the 1700s. Without help from the government under which they lived and, for the most part, the society around them, Black women long provided virtually all the social services available to African Americans.

Janie Porter fulfilled the expectations of her school and her community. She married a fellow Hampton student, Harris Barrett, and started the Locust Street Settlement House in a room of their home. The Barretts were able to save enough money to install plumbing in their home but used it instead to acquire a building for the settlement house. Hampton students volunteered as teachers, and along with woman volunteers, helped create quilting and sewing clubs, a children’s garden, adult education classes and many other services to the people of Hampton, Virginia. She also founded the Virginia State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs and served as its president until 1932.

Questions to Consider:

- How were the lives of Jane Addams and Janie Porter Barrett different? How did that affect what they did to help others?

- How were “true womanhood” and “noble womanhood” different as ideals? How did they affect the expectations family and society had of individual women?

- Given the sacrifices families made to educate their daughters, were the families right to expect them to use their education in the service of the Black community?

Beyond the Settlement House

“[O]ther institutions, which neither practitioners nor examiners of settlement work have traditionally considered part of the settlement movement, did conduct a version of settlement work in black communities. This history, however, articulates an expanded definition of settlement work that embraces those efforts among blacks incorporating the settlement movement’s dual commitment to provide a vast array of social service, educational, and recreational programs, and to usher in sweeping social change. Expanding the regional scope beyond the northern and midwestern metropolis and the temporal reach beyond the Progressive Era predicates such an encompassing notion.”

Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, Black Neighbors: Race and the Limits of Reform in the American Settlement House Movement, 1890-1945

Since the wave of scholarship about the history of Black women began in the 1980s and 1990s, some recognition has been given to the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which was formed in 1896. But there has been a tendency to assume that was the beginning of the Black women’s club movement. This is very far from the truth, and it is one of many reasons that Black women have not been fully recognized for their part in the Progressive Era reforms. Their work often, in fact usually, did not fit the settlement house model, and it began long before the end of the nineteenth century.

![Black and white photograph from the shoulders up of a Black woman looking into the camera. She wears a dress with a high collar and has her hair piled on her head. The caption below the image reads, "In 1900, at the annual meeting of the National Baptist Convention, Nannie Helen Burroughs delivered a speech entitled 'How the Sisters Are Hindered from Helping.' It led to the establishment of the Women's Convention. [Moorland-Spingarn]."](https://dcc.newberry.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/991073298805867_ord_e_185_86_b542_1993_vol_01_pg_091_01-642x1024.jpg)

Black women have been coming together to support each other and the Black community in an organized way since the 1700s. The Free African Society was created in 1787 in Philadelphia by Black women and men, but in 1793, women created the Female Benevolent Society of St. Thomas to take over all the charitable work of the group. By 1838, there were 119 mutual benefit societies in Philadelphia alone. These groups often expanded their focus to abolition and to suffrage, but they continued to provide services to the Black community.

At the end of the nineteenth century, W. E. B. Du Bois declared that there were so many Black women’s mutual aid societies across the country that he found it “impractical to catalog them.” He estimated the number in the thousands. As Walter Weare wrote in Black Women in America, “In Petersburg, Virginia, Du Bois gave up after listing twenty-two mutual benefit societies, at least half of which were women’s associations like the Sisters of Friendship, the Ladies Union, the Ladies Working Club, the Daughters of Zion, the Daughters of Bethlehem, the Loving Sisters, and the Sisters of Rebeccah. It was in nearby Richmond, however, that the mutual benefit society among Black women assumed its highest stage of development in a century-long evolution from folk networks among female slaves to national organizations among professional women…”

Weare is referring here to the Independent Order of St Luke. Founded as the United Order of St. Luke by a freedwoman named Mary Prout in 1867 in Boston, its initial purpose was to provide burial insurance to Black women who had no other access to it. Men were also allowed to join. In 1869, the group split, and one of the two factions moved to Richmond to become the Independent Order of St. Luke.

![Black and white photograph of a large room filled with Black women working at desks covered in paper and typewriters. The caption under the photograph reads, "The Independent Order of St. Luke was founded in 1867 by an ex-slave, Mary Prout. By 1899, the order had fallen on hard times, and might have ceased to exist had it not been for Maggie Lena Walker. Under her leadership, by 1920 the Order of St. Luke had been more than 100,000 members in twenty-eight states and had created the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, a weekly newspaper, and a department store, and generally had become a collective force to reckon with in Richmond, Virginia, where the organization was headquartered. Pictured here is their office force. [National Park Service]."](https://dcc.newberry.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/991073298805867_ord_e_185_86_b542_1993_vol_02_pg_0829_01-1024x808.jpg)

Maggie Lena Walker joined the Order as a teenager and, at thirty-five, she took over leadership of the organization. During her tenure, the Order created a newspaper, a department store, and the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, of which she was president, becoming the first woman bank president in the country. This may seem miles away from a settlement house, but she was addressing what she saw as the most pressing need of the Black community—jobs. The Order of St. Luke and others like it became instruments for economic self-determination, while still others grew into the influential Black women’s club movement.

As Jim Crow came to rule the South after Reconstruction, the Black community was faced with poverty, illiteracy and discrimination on a scale that is difficult to describe or even imagine. White government agencies clearly had no intention of providing services to this community, so the National Association of Colored Women, the Phillis Wheatley Association, the Women’s Convention of the Black Baptist Church, and a host of small groups stepped up, often financing their efforts with dues of a nickel a week, bake sales, and selling handmade goods.

Often individual women saw needs and stepped in to fill them, as Janie Porter Barrett did in Virginia. In Rochester, New York, for example, Isabella Dorsey created the Dorsey Home for Dependent Colored Children. Victoria Earle Matthews created the White Rose Mission in New York City. Judith C. Horton created a library for the Black community in Guthrie, Oklahoma.

Just as often, groups of women organized to provide social services. When members of the Ida B. Wells Club discovered that none of Chicago’s sixteen kindergartens would accept Black children, they opened a kindergarten themselves, in the Bethel African American Episcopal Church. In 1914, clubwomen in Milwaukee opened the Milwaukee Home for Colored Working Girls and the Home for Friendless Colored Women and Girls.

These efforts took place around the country, in every state and every city. And they were a crucial part of saving the cities.

Questions to Consider:

- Is “settle house movement” an accurate description of the work women did during the Progressive Era? Why or why not?

- What was the importance of the work of Black women to their communities and to the cities in general?

- What were the advantages and disadvantages for Black women of the tradition of “noble womanhood”?

Conclusion

These are the women who saved the cities. White women and women of color. Rich women, poor women, and women of the middle class. And there is yet another story to be told about the ways in which they persuaded government agencies to follow their lead and create the social services that we take entirely for granted today, from sanitation to building inspections to hospitals for all our citizens. And yet, according to Daphne Spain, “Historian Thomas Bender has observed that ‘it is embarrassing how rapidly life in our cities is coming to resemble the circumstances of a century ago, when Jane Addams founded Hull House.’ Most Americans would agree that the city still needs saving.’”

About the Author

Kathleen Thompson is a writer and historian, best known for A Shining Thread of Hope: The History of Black Women in America, which she co-authored with prominent Black women’s historian Darlene Clark Hine. This essay was made possible by a Fellowship from the National Society of Daughters of the American Revolution–Chicago Chapter.

Explore the related activity “Population Growth in Chicago” here.

Curriculum Connections: Immigration, Industrialization, Progressive Era, Visual Literacy

The lesson plan “The Hull House Neighborhood” also explores Jane Addam’s settlement house.

Curriculum Connections: Chicago History, Immigration, Progressive Era, Settlement House Movement

Click on the images below for high resolution versions.

The Women Who Saved the Cities

Chicago in the 1890s

The Settlement House Movement and Beyond

Books About This Period

Duis, Perry R. Challenging Chicago : Coping with Everyday Life, 1837-1920. Urbana: University of Illlinois, 1998.

Hendricks, Wanda A. Gender, Race, and Politics in the Midwest: Black Club Women in Illinois. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1998.

Hendricks, Wanda. “Alpha Suffrage Club.” Encyclopedia of Chicago Online. Chicago Historical Society, 2005.

Hine, Darlene Clark, with Elsa Barkley Brown, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn. Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Brooklyn, New York: Carlson Publishing, 1993.

Hunter, Robert. Tenement Conditions in Chicago: Report by the Investigating Committee. Chicago: City Homes Association, 1901.

Knight, Louise W. Citizen: Jane Addams and the Struggle for Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Prees, 2005.

Lash-Quinn, Elisabeth. Black neighbors: Race and the Limits of Reform in the American Settlement House Movement, 1890-1945. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

Philpott, Thomas Lee. The Slum and the Ghetto: immigrants, Blacks, and Reformers in Chicago, 1880-1930. Belmont, California: 1991.

Shaw, Stephanie J. What a Woman Ought to Be and to Do: Black Professional Women Workers During the Jim Crow Era.

Spain, Daphne. How Women Saved the City. Minneapolis ; London : University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

![Black and white photo from the bust upwards of a Black woman in a high-collared dress decorated with buttons. She wears her hair up. The caption reads "Rejecting suggestions that she pass for white, Janie Porter Barrett became one of the foremost Black organizers in the social settlement movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. [Hampton University Archives]"](https://dcc.newberry.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/991073298805867_ord_e_185_86_b542_1993_vol_01_pg_086_01-748x1024.jpg)