Themes

African American History

The Caribbean

Early Modern Race

Enslavement

Indigenous History

Periods & Events

Early Modern Period

British Empire

Skills & Document Types

Image Analysis

Close Reading

Source Comparison

Uncovering Resistance

Please note, this lesson includes discussion of enslavement and racist descriptions of people of color in a historical source.

Materials – Available for Download in the Downloads Tab:

- A copy of the lesson “Resistance in the Colonial Caribbean (Advanced)”

- Images of from The State of Barbados (high-resolution version) and A True & Exact History of Barbados (high-resolution version)

- Transcripts of excerpts from The State of Barbados and A True & Exact History of Barbados

- Source analysis worksheet

Purpose & Learning Objectives

This lesson will help students see evidence of marginalized peoples actively resisting the injustice of colonization and enslavement in the 1600s.

At the heart of the lesson are two sources from the seventeenth century—a bureaucratic document and a printed book—that contain information about the English colony on Barbados. As students will see, these sources give two very different accounts of the actions and experiences of Black and Indigenous communities on and around Barbados. This lesson will help students understand how analyzing these sources in relation to each other can help recover stories of Black and Indigenous resistance that white European enslavers deliberately tried to erase.

At the end of the lesson, students will understand some key points about history and traditionally marginalized communities. These points include:

- There is clear historical evidence that marginalized communities actively resisted colonizers and enslavers in the seventeenth century.

- These stories are often highly distorted or erased altogether in sources created by white European authors, especially when those sources were intended for white European audiences.

- Despite these attempts at erasure, it is possible to recover the histories and experiences of marginalized groups through archival research, especially when that research uses sources that public audiences were never supposed to see.

Process

This lesson is for a teacher-controlled class. However, students can also perform this lesson independently or in small groups. For this option, download the copies of the source images in the Downloads tab or give them the link to the Newberry collections.

The structure for this lesson is intended for a full class session. It involves three steps: image study, excerpt study, and reflection. By following these steps, the students will learn how to ask and answer the questions necessary to find the stories of marginalized peoples hidden under the surface of primary sources created by enslavers and colonizers.

Historical context on this period and more information on the source in the Background section below.

Step 1: Image Study

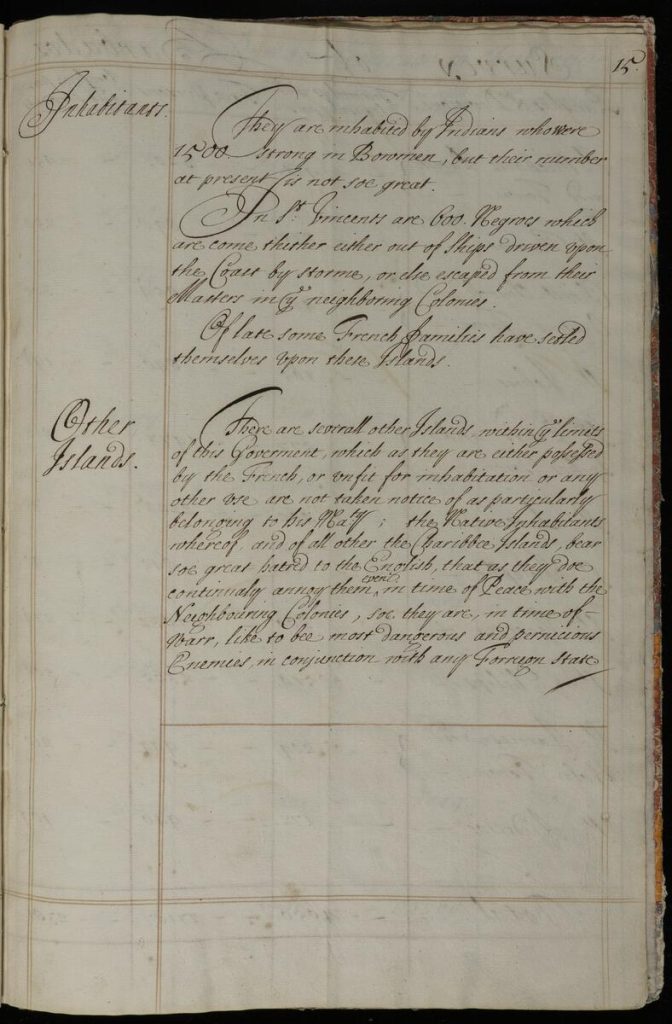

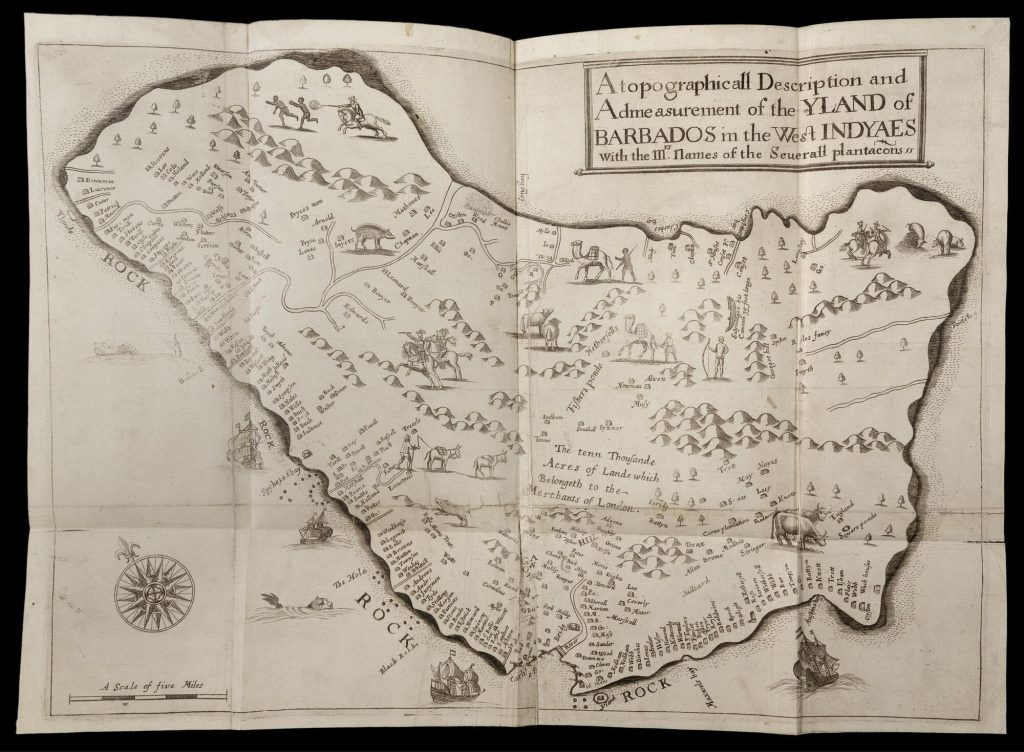

Begin by showing students images from each source. For this stage, any images are fine, but the most important page to focus on in The State of Barbados is p. 15 of the document, while the most important images from A True & Exact History are the title page and map.

There are two possible ways to run this step:

- Have all students look at the same source together, one after another, or

- Break the students into two or more groups and assign them only one source to study.

Either way, give the students some time to look at the image(s) and describe what they see. Use the student source analysis worksheet available in the Downloads Tab if you like. A source analysis worksheet for this step is in the Downloads tab. After reviewing the images, have the students answer the following questions:

- What is this source? How would you describe it?

- What sorts of information does this source contain?

- What was the intended audience for this source?

- What does the creator of each source want his audience(s) to know about Barbados?

- Which source do you find easier to read? Why?

Takeaways

Through this comparison, the students should be able to explain how different these sources are. Each one is meant for a different audience, with the printed book more clearly aimed at a public audience, and the document more for a limited, “private” audience. Recognizing this difference is essential for understanding the sort of information about marginalized communities each source contains.

Step 2: Excerpt Study

After the image study, either display or distribute an excerpt showing information about the activities and mindsets of two historically marginalized communities in the sources: enslaved Black Africans and colonized Indigenous peoples. Use the student source analysis worksheet available in the Downloads Tab if you like.

Note on Reading the Excerpts

Reading seventeenth-century English colonial sources is difficult even for experts. The following are some challenges that students may encounter when performing this step….

- Content – As with any colonial source, both sources here speak directly about the violent and dehumanizing aspects of enslavement. Teachers should be sure their students are prepared to encounter this content before reading the excerpts.

- Language – These sources use the term “Negroes” to refer to enslaved Black people from West Africa, and “Native” to refer to Indigenous communities in Barbados. These were commonly used terms at the time, but teachers are encouraged to use more respectful terms (e.g., “enslaved West Africans” or “Indigenous communities”) when discussing the excerpts.

- Spelling – The English language did not have firm rules for spelling in the 1600s, so students may find these excerpts very difficult to read. Remind the students that reading the words out loud is a helpful way to figure out difficult words, and that they do not need to understand every single word to make sense of the excerpts.

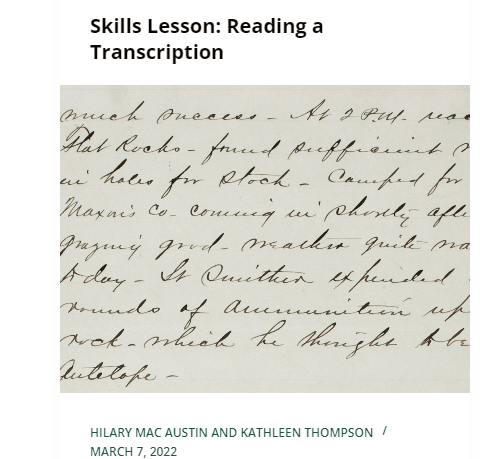

For more on reading a transcription, use this Skills Lesson.

Excerpt 1: Annoying the English

In St. Vincents [an island near Barbados] are 600 Negroes [i.e., enslaved West Africans] which are come thither either out of Ships driven upon the Coast by storme, or else escaped from their Masters in (the) neighboring Colonies.

There are several other Islands within (the) limits of this [colonial] Government, which as they are either possessed by the French, or unfit for inhabitation or any other use are not taken notice of as particularly belonging to his Majesty [the king of England]; the Native Inhabitants whereof, and of all other the Caribbe Islands, bear so great hatred to the English, that as they doe continualy annoy them, even in time of Peace with the Neighbouring Colonies, soe they are in time of Warr, like to be most dangerous and pernicious Enemies, in conjunction with any Forreign State.

The State of Barbados, 15

After reading the source, have the students discuss what it tells them about the actions, motivations, and mindsets of Black Africans and Indigenous peoples in 1684. Some guiding questions to help with this discussion include:

- Other than the English, what groups or communities does this excerpt describe?

- What are the Black Africans and Indigenous people doing in this excerpt?

- In particular, have the students think about what “annoy” means. Though it sounds fairly tame to us, in the seventeenth century the word meant “to attack.”

- How does the English author of this excerpt seem to feel about what Black Africans and Indigenous people are doing? (Pay special attention to the final sentence of the excerpt).

Takeaways

Despite its odd language, this excerpt should make clear to the students that the Black Africans and Indigenous people not only recognized the injustice and brutality of colonization and enslavement in the 1600s, but were also willing to violently resist them. The author of this document, at least, also recognized how the “hatred” of these communities toward the English represented a real threat to the very existence of an English colony on Barbados.

Excerpt 2: A Failed “Mutinie”

Note: In this excerpt, the author, Richard Ligon, is responding to stereotypes white English people had about Black Africans. Enslavers and their supporters repeatedly insisted that West Africans were naturally untrustworthy, violent, and, so to speak, “uncivilized,” so that they could justify enslaving them. Ligon acknowledges these stereotypes in the passage below when he writes that the enslaved Africans who reported the rebellion “…hated mischief, as much as they [those who planned to rebel] lov’d it.”

…it was in a time when Victuals [i.e., “food”] were scarce, and Plantins were not then so frequently planted, as to afford them [i.e., enslaved Africans] enough [to eat]. So that some of the high spirited and turbulent amongst them, began to mutinie, and had a plot, secretly to be reveng’d on their Master…. These villains, were resolved to make fire to such part of the boyling house, as they were sure would fire the rest [of the enslaver’s house] and so burn all, and yet seem ignorant of the fact, as a thing done by accident. But this plot was discovered, by some of the others [i.e., other enslaved Africans] who hated mischief, as much as they lov’d it; and so traduc’t [i.e., betrayed] them to their Master and brought in so many witnesses against them, as they were forc’t to confesse…. …the Master gave order to the overseer that [the betrayers] should have a dayes liberty to themselves and their wives…and…a double proportion of victual [food] for three dayes, both which they refus’d: which we all wonder’d at, knowing well how much they lov’d their liberties, and their meat, having been lately pincht [i.e., restricted] of the one and not having overmuch of the other; and therefore being doubtfull what their meaning was in this, suspecting some discontent amongst them…. [They answered that] they would not accept any thing as a recompence [i.e., reward] for doing that which became them in their duties to due, nor would they have him think, it was hope of reward, that made them accuse their fellow servants, but an act of Justice, which they thought themselves bound in duty to doe, and they thought themselves sufficiently rewarded in the Act.

A True & Exact History, 53-54

After reading, have the students discuss what this excerpt says about the experience of enslaved Africans in Barbados. Some guiding questions to help this discussion include:

- How does Ligon describe the Black Africans who decided to “mutinie” against their enslaver? (“high spirited”, “turbulent”, “villains”)

- Why did they decide to do this? (Lack of food)

- Why does the attempted mutiny fail? (“this plot was discovered by some of the others”)

- According to Ligon, why did other enslaved Africans decide to turn in the mutineers? (“an act of Justice…”)

- According to Ligon, why did the people who turned in the mutineers refuse a reward? (“they would not accept any thing as recompense…”)

- Do you think this story as Ligon tells it is true? Do you think it could be partly true? Why or why not? What do you think Ligon’s telling leaves out?

- By including this story in his book, what does Ligon want his audiences to think about Black Africans and Indigenous people on Barbados?

Step 3: Reflection and Comparison

In the final step of the lesson, the students will consider why these sources tell such different stories about people of color in 17th-century Barbados through comparing these very different accounts. Have them compare what they found in the excerpts from each source.

Guiding questions to help this discussion include:

- Compare the information about the actions of African and Indigenous people in and around Barbados in the 1600s. Are these sources telling similar stories? How are they different?

- What did the creators of these sources want their audiences to think about the English colony of Barbados?

- Why did the creators of these sources feel it was important to include these stories?

- Which source do you think tells a more accurate story about these communities? Why?

- Were you surprised by any of the information you found in these sources?

- After reading these sources, what do you now know about the experience of marginalized communities in Barbados in the 1600s?

- How did the information you found about marginalized communities in these sources make you feel?

- Do these sources make you think or feel differently about the world you see now?

- What new questions do you have about these sources or this history?

Background

Historical Context

In the seventeenth century, England rapidly increased its efforts to become a colonial power by claiming islands throughout the Caribbean Sea. The English forcibly took possession of Barbados in the 1620s, although Indigenous communities continued to live on the island thereafter. The colony’s main export was sugar; English plantation owners imported thousands of enslaved West Africans to perform the extremely difficult and dangerous work on the sugar plantations and in the processing plants.

The State of Barbados

This source is a hand-written bureaucratic document produced by the English colonial administration in Barbados around the year 1684. It includes various statistical and economic information about the colony, such as the number of white, Indigenous, and African people on the island, exports and imports, revenues and expenses, details on the number of plantations, and so on. It was likely never meant to be seen by anyone other than colonial and government officials in Barbados and England.

A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbados

This book, written by Richard Ligon, was first printed in London in 1657. Based on Ligon’s time living in Barbados from 1647 to 1650, the book includes the history, environment, plants and animals, and people of Barbados, as well as a highly-detailed description of the sugar industry on the island, which Ligon knew all about from investing in a sugar plantation in 1647. The large size of the book, the map, and the detailed engravings make clear that this book was designed to appeal to a wealthy and literate English audience, the sort of people who could invest their own money in the sugar industry on Barbados.

About the Author

Christopher D. Fletcher is the Assistant Director of the Center for Renaissance Studies, where he often shares the Newberry’s pre-1800 collections with the public through in-person collection presentations, exhibitions, social media, and digital resources. He earned his PhD in Medieval History from the University of Chicago in 2015. His research and teaching focus primarily on religion and public engagement before 1800. He has published articles and book chapters and co-edited volumes on various forms of public outreach in medieval and early modern Europe and the digital humanities, and his current book project, Public Engagement in the Middle Ages: Medieval Approaches to a Modern Crisis, uses medieval practices of public engagement to prepare medievalists to more effectively reach diverse audiences today. He was a co-curator of the Seeing Race Before Race exhibition, and discussed The State of Barbados on dozens of gallery tours.

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the lesson “Resistance in the Colonial Caribbean (Advanced)”

- Images of from The State of Barbados (high-resolution version) and A True & Exact History of Barbados (high-resolution version)

- Transcripts of excerpts from The State of Barbados and A True & Exact History of Barbados

- Source analysis worksheet

Related Lessons

Third lesson based on Seeing Race before Race coming soon!

Additional Resources on this Topic

- Alana Edmundson, “Entry #7: The State of Barbados,” from Seeing Race Before Race.

- Rebecca L. Fall, Records From Barbados Are Far From Mundane

- Sarah Peters Kernan, “Sugar and Power in the Early Modern World,” Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom