Themes

Food History

History of Medicine

History of Science

Humoral Theory

Periods & Events

Early Modern Europe

Skills & Document Types

Close Reading

Materials – Available for Download in the Downloads Tab

- A copy of the “Food, Health, and the Humors in Early Modern Europe” lesson

- Transcriptions of source excerpts used in this lesson

- Images of the sources used in this lesson (find high resolution versions of all images here)

- Source analysis worksheet

Process

You and your students are going to read a series of excerpts from early modern (ca. 1500-1700) European books. Some of these books are primarily about food, while others are about health; all of the excerpts, however, are focused on how specific foods and eating were thought to impact a person’s health at the time. Food was seen as an important way to maintain a person’s health or heal a sick body. All of these sources provide insight into how early modern people used food to manipulate their health.

Humoral theory is the foundation of any exploration of food and health in the early modern period. This was the predominant medical system from Antiquity until approximately the eighteenth century. In this system the human body was governed by four humors or fluids: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Learn more in the Background section below.

This lesson is for a teacher-controlled class. Each of the five texts are excerpts from primary sources. Sources 1, 2, and 3 are shorter, easier to read, and focus on a single ingredient familiar in the present day. They may be easier for most students. Sources 4 and 5 are more difficult, as they deal with broader ideas about health and eating rather than individual ingredients. More information is included with each source.

Words that may be particularly challenging or new are listed below each source in “Words to Know.” Terms pertaining to the humors or temperaments may also be new to students; these are included in the Background section below.

This lesson can be taught in several ways based on the time available and the grade level of students. You can use all five sources or focus on the first three sources. You can also tailor the lesson to individual work, small group work, or working together as a class. You can divide the class into small groups, with each group focusing on 1 or 2 texts. Or, you may decide that individual work or working together as a class is a better fit for your classroom.

A source analysis worksheet is provided in the Downloads tab to help students analyze the sources.

Examining the Sources

Display or distribute the sources and the source analysis worksheet, if you choose to use it.

Explain that the texts are excerpts from five different sources printed in Europe between 1557 and 1691. Texts printed during this time present some difficulties for modern readers. First, all of the sources include some letter forms that seem strange. The lower-case “s” and “f” look similar, and some letters are used interchangeably, including y/i and u/v. Students may also encounter a vowel with a line over it, like “ē.” This indicates there is an “n” or “m” after the vowel that has been omitted in the text. Finally, spelling was not standardized at this time. If a word seems confusing or misspelled, try saying it out loud and it will likely make more sense.

If possible, have students read the sources and write down their observations without providing any additional information or context. Some information about humoral theory may be helpful or needed before students engage with the sources. Encourage students to collect as much as they can from each source and develop their own questions about it. Then, discuss their questions (or the questions provided after each source) to spark collaborative exploration and discussion of the sources. Possible questions to prompt a comparison and synthesis of all the texts are listed below.

If you would like your students to work with the sources independently or in small groups, download the Student Worksheet in the Downloads tab. You can also download images of the original sources in the Downloads tab.

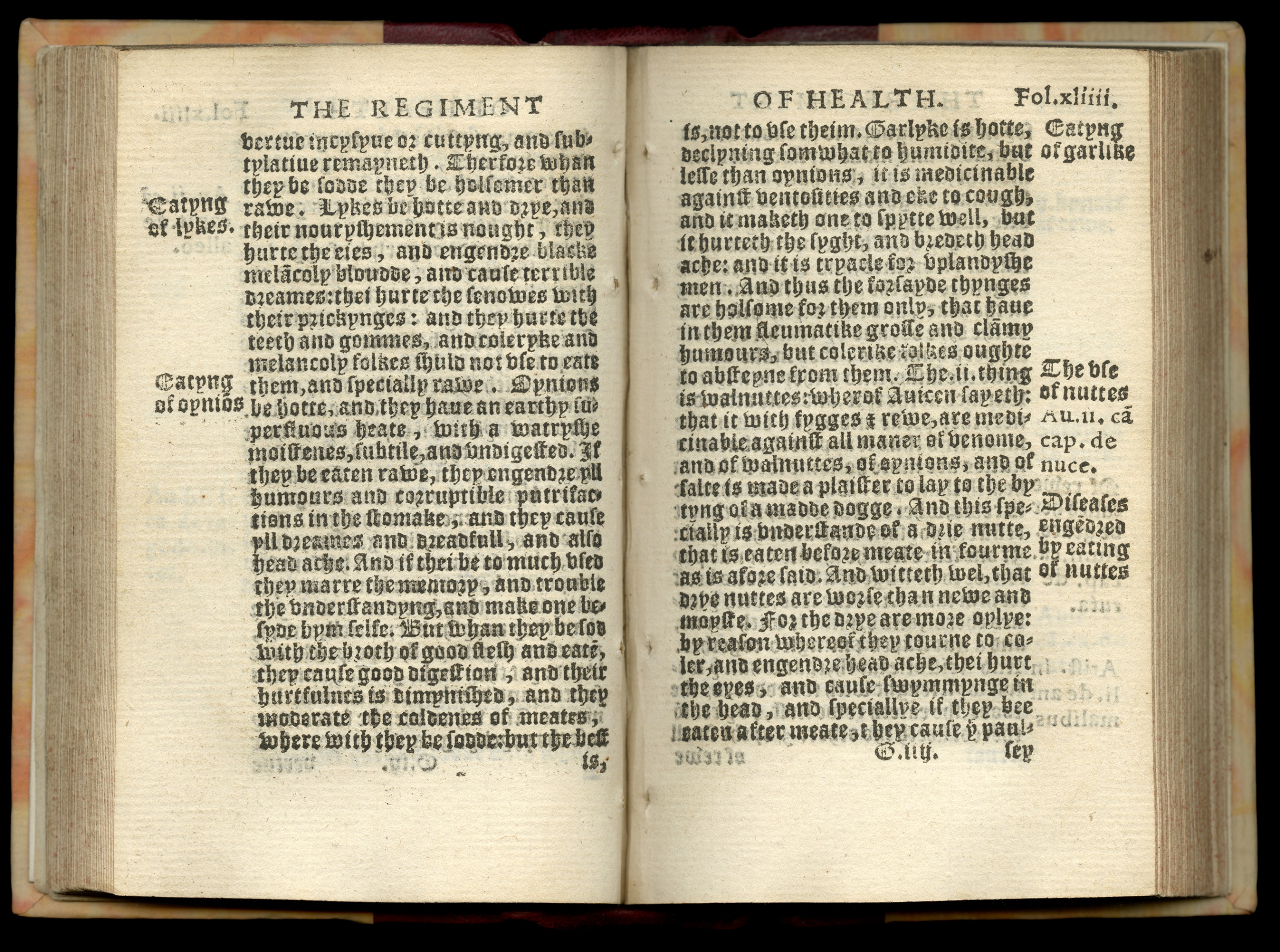

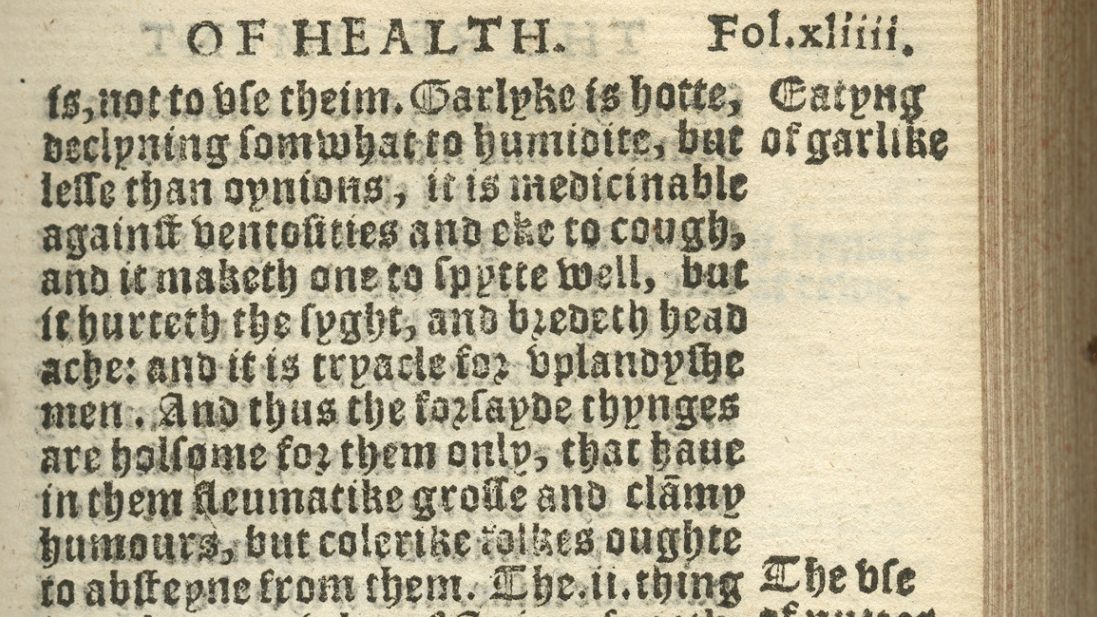

Source 1: Excerpt on Garlic from Regimen saitatis Salerni (1557)

Source 1 is very short, but can be difficult to read due to the typescript (font), spelling, and vocabulary. You may decide to have advanced students work through these challenges, or you may use the modernized transcription included here.

The Regimen sanitatis Salerni (or Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum) is a late-thirteenth or early-fourteenth-century Latin commentary on a twelfth-century poem about health. While the poem’s origins are murky, it is broadly attributed to the medical school in Salerno, Italy founded in the ninth century. The school was famous for its teaching and scholarship rooted in Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Persian thought. The Latin Regimen was widely circulated around medieval Europe in manuscript form, and then printed and translated regularly by the late fifteenth century. Thomas Paynell (fl. 1528 – d. 1567), an English friar and canon, translated this version of the Regimen, which was printed in seven editions.

The Regimen teaches readers about the humoral system and describes how a life of moderation can improve physical health. Much of the text is focused on diet, detailing the positive and negative effects of specific foods and drinks. The Regimen also instructs readers about daily habits, such as sleeping and urinating.

Transcription:

Garlyke is hotte, declyninge somwhat to humidite, but lesse than oynions, it is medicinable against ventosites and eke to cough, and it maketh one to spytte well, but it hurteth the syghte, and bredeth head ache: and it is tryacle for vplandyshe men. And thus the forsayde thynges are holsome for them only, that haue in them fleumatike grosse and clāmy humours, but colerike folkes ought to absteyn from them.Modernized Transcription:

Garlic is hot, declining somewhat to humidity, but less than onions. It is a medicine against flatulence and also coughing, and it makes one spit well, but it hurts the sight and causes headaches, and it is an antidote for homely men. And thus the foresaid things are wholesome for them only, that have in their bodies phlegmatic and clammy humors, but choleric folks ought to abstain from them.

Words to Know

- Ventosites/ventosities: an accumulation of gaseous pressure in the body, flatulence

- Eke: also

- Tryacle/triacle: an antidote for poison or venom

- Vplandyshe/uplandish: homely, rustic, crude

- Grosse: of a body, in a body

Close Reading Questions

- What is this excerpt about? What kind of book do you think this excerpt is from? How do you know?

- How did eating this food impact one’s health? Are there any good effects from eating it? Any bad effects?

- Who should eat this food? Who should avoid this food?

- How does one’s temperament (or dominant humor) affect whether or not they should consume this food?

- Does the author compare garlic to any other foods? Are these two foods compared or paired together often today?

- Does the information the author provides about this food seem logical? Do you think it seemed reasonable at the time it was written? Why?

- How closely do you think people followed these rules?

- How do you think someone’s social status affected whether they could eat this food? Or whether they thought they should?

Analysis Questions

- Are there any clues to who may have written this text? What are those clues?

- Are there any clues to who may have read or used this text? What are those clues?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What questions do you have after reading this excerpt? Where could you find answers to your questions?

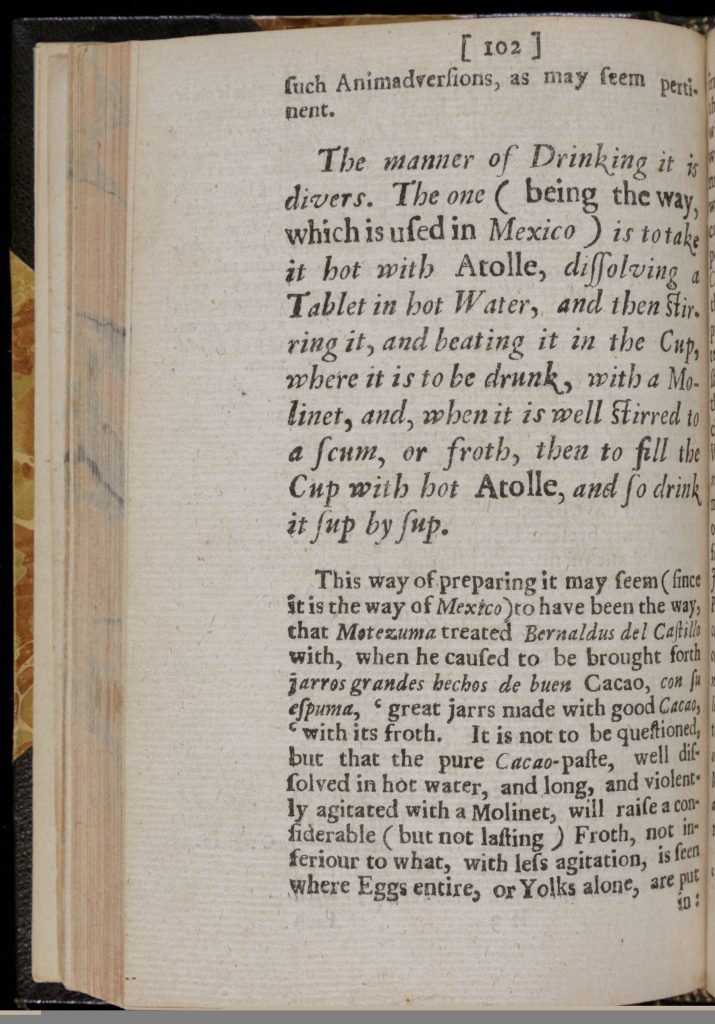

Source 2: Excerpt on Chocolate from Henry Stubbe’s The Indian Nectar (1662), pp. 102-104

Click the image on the right to access the entire excerpt or download a copy in the Downloads tab. Begin with “The manner of Drinking it is divers.”

Henry Stubbe’s The Indian nectar (1662) is a book entirely dedicated to the topic of chocolate. Chocolate was still a relatively new, exotic, and expensive food in Europe in the mid-seventeenth century. Stubbe was an English physician, and he wanted to convince readers about the curative properties of chocolate. He also wanted to advertise his services as a physician who would prescribe chocolate concoctions to his patients. Stubbe wrote this book by collecting writings by other European authors and physicians. He not only copies lengthy quotations from other sources, but also translates the texts and provides commentary on the efficacy of the recommended cures.

Words to Know

- Molinet: a tool used to agitate drinking chocolate to create froth on top of the beverage

- Atolle/atol: a hot masa-based beverage

- Pochol/pozol: fermented corn dough

- Paniso/panizo: millet

- Maiz/maize: corn

Close Reading Questions

- What is this excerpt about? What kind of book do you think this excerpt is from? How do you know?

- How did eating this food impact one’s health? Are there any good effects from eating it? Any bad effects?

- Who should eat this food? Who should avoid this food?

- How does one’s temperament (or dominant humor) affect whether or not they should consume this food?

- How does the preparation of chocolate affect how healthy it is?

- Does the information the author provides about this food seem logical? Do you think it seemed reasonable at the time it was written? Why?

- The author is writing for an audience in England. Why does he include so much historical information about chocolate and information from Spanish-language sources?

- How closely do you think people followed these rules?

- How do you think someone’s social status affected whether they could eat this food? Or whether they thought they should?

Analysis Questions

- Are there any clues to who may have written this text? What are those clues?

- Are there any clues to who may have read or used this text? What are those clues?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What questions do you have after reading this excerpt? Where could you find answers to your questions?

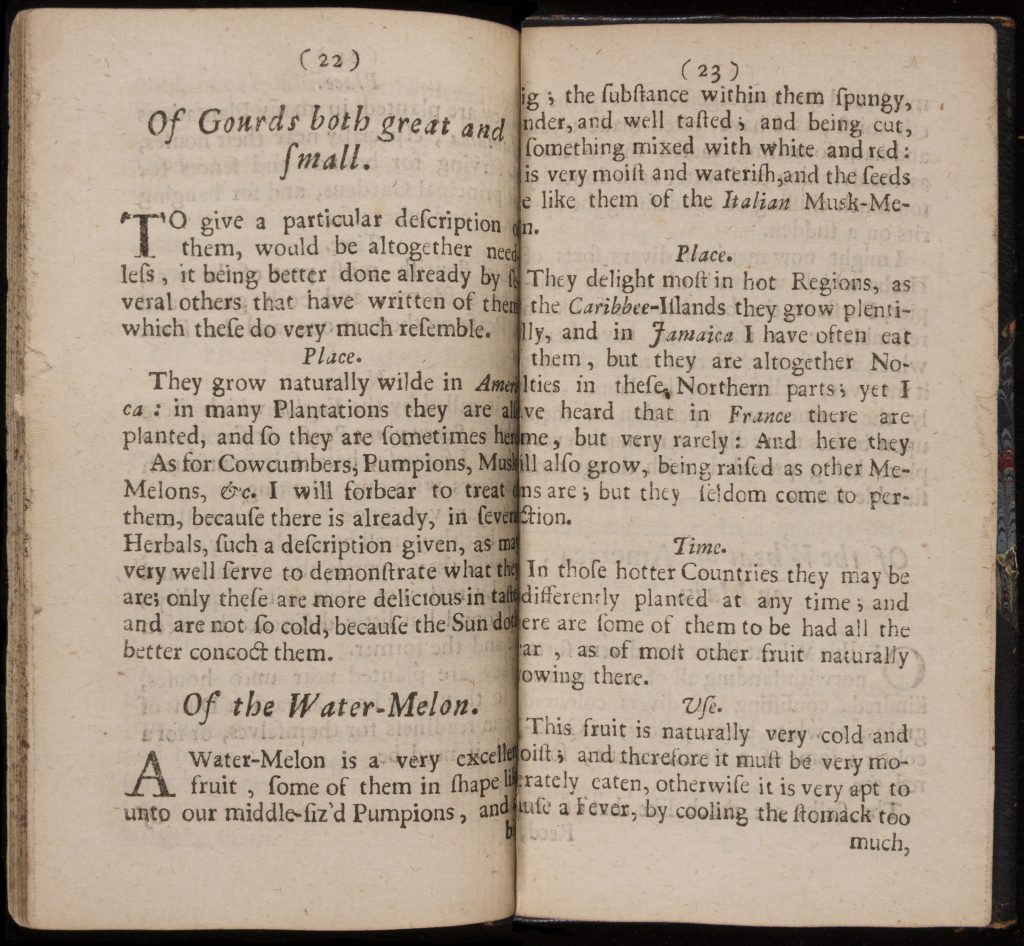

Source 3: Excerpt on Watermelon from William Hughes’ The American physitian (1672), pp. 22-24.

Click the image on the right to access the entire excerpt or download a copy in the Downloads tab. Begin with “Of the Water-melon.”

William Hughes, an English botanist (and possibly a medical practitioner), travelled to the Americas in the 1650s. His experiences touring British plantations in the Caribbean, particularly in Jamaica, and recording information about the plants there, led to the publication of The American physitian in 1672. Hughes offers botanical descriptions, details about the humoral properties of the edible plants, and even provides cooking recommendations of foods like potatoes, watermelon, sugar, corn, and prickly pear.

Close Reading Questions

- What is this excerpt about? What kind of book do you think this excerpt is from? How do you know?

- How did eating this food impact one’s health? Are there any good effects from eating it? Any bad effects?

- Who should eat this food? Who should avoid this food?

- How does one’s temperament (or dominant humor) affect whether or not they should consume this food?

- Does the information the author provides about this food seem logical? Do you think it seemed reasonable at the time it was written? Why?

- Is watermelon an exotic food, or difficult to obtain in Europe at the time this source was written? How might that affect the author’s description of the food and its healthful properties?

- How closely do you think people followed these rules?

- How do you think someone’s social status affected whether they could eat this food? Or whether they thought they should?

Analysis Questions

- Are there any clues to who may have written this text? What are those clues?

- Are there any clues to who may have read or used this text? What are those clues?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What questions do you have after reading this excerpt? Where could you find answers to your questions?

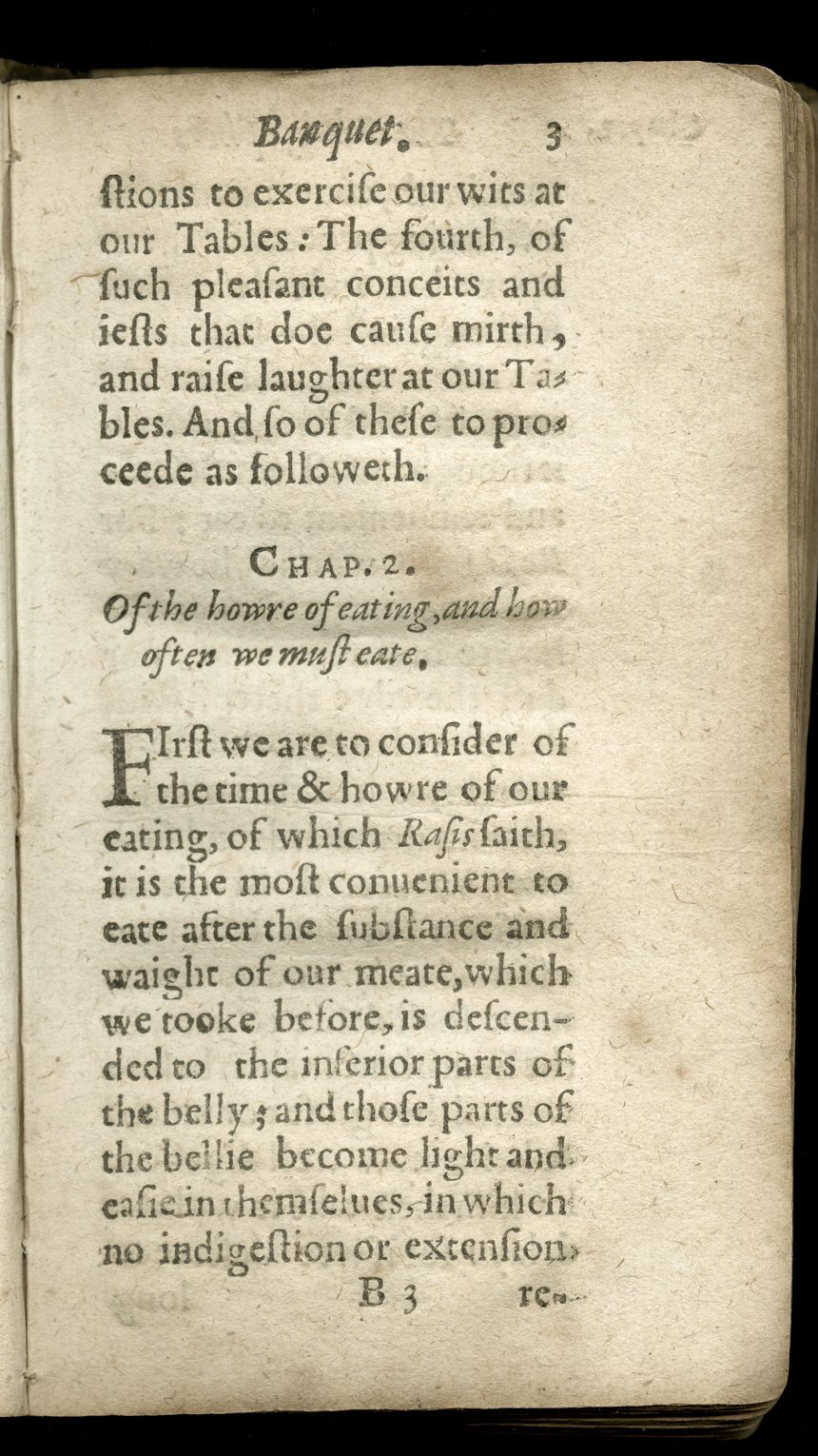

Source 4: Excerpt on When and How to Eat from The phliosphers banqvet (1609) fol. 3r-5r

Click the image on the right to access the entire excerpt or download a copy in the Downloads tab. Begin with “Chap. 2. Of the howre of eating, and how often we must eate.”

The philosophers banqvet (1609) is an English translation of Mensa philosophica, a medieval compilation of texts about diet and health. It is attributed to either Theobaldus Anguilbertus, a medieval physician, or Michael Scotus, a medieval scholar. Mensa philosophica was designed to be both didactic and entertaining for highly educated readers. The text regularly draws upon Arabic, Greek, and Latin sources spanning a range of scientific and medical topics.

Words to Know

- Rasis/Rhazes/Abū Bakr al-Rāzī: A Persian physician and philosopher (c. 865-925 CE) who wrote over 200 scientific texts, including several on the topic of food and health

- Consuetudo est altera natura: “Habit is second nature”

- Averrois the Commentor/Averros the Commentator/ Ibn Rushd: An Andalusian physician, philosopher, and judge (1126-1198 CE) known for his prolific writings on many topics, including commentaries on Aristotle

- Avicens/Avicenna/Ibn Sina: A Persian physician and philosopher (980-1037 CE) whose prodigious writings form the foundation of early modern medicine

Close Reading Questions

- What is this excerpt about? What kind of book do you think this excerpt is from? How does the time a person eats and how often a person eats impact their health?

- How does one’s temperament (or dominant humor) affect when and how often they should consume food?

- Where is the author getting his information?

- Does the information the author provides seem logical? Do you think it seemed reasonable at the time it was written?

- How closely do you think people followed these rules?

- Do you think a reader’s social status influenced whether nor not they were able to follow the author’s rules? Why?

Analysis Questions

- Are there any clues to who may have written this text? What are those clues?

- Are there any clues to who may have read or used this text? What are those clues?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What questions do you have after reading this excerpt? Where could you find answers to your questions?

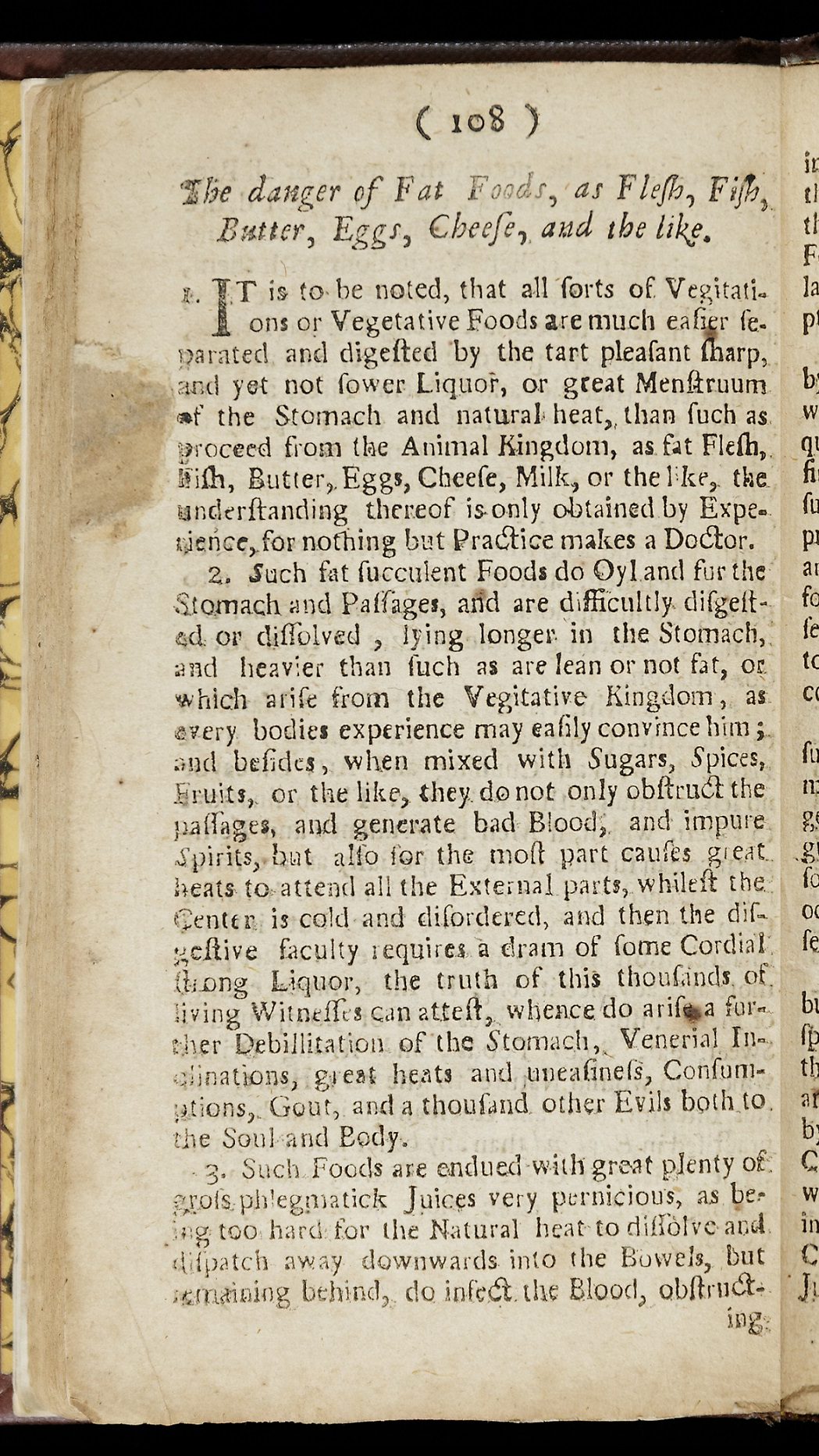

Source 5: Excerpt on Eating Meat and Animal Products from Thomas Tyron’s Wisdom’s dictates (1691) pp. 108-109

Click the image on the right to access the entire excerpt or download a copy in the Downloads tab. Read paragraphs 1-3 of “The danger of Fat Foods, as Flesh, Fish, Butter, Eggs, Cheese, and the like.”

Thomas Tryon was a seventeenth-century English sugar merchant and author. He was an Anabaptist and advocated for animal rights and vegetarianism. In Wisdom’s dictates (1691), Tryon argues that readers could attain a healthier life by following a vegetarian diet and refraining from eating animals. While most of the book consists of Tryon’s thoughts on leading a godly life, he also provides a list of foods that conform to his vegetarian diet.

Words to Know

- Menstruum: a solvent, a substance that can dissolve something else

- Consumption: tuberculosis, a disease that mainly affects the lungs

Close Reading Questions

- What is this excerpt about? What kind of book do you think this excerpt is from? How do you know?

- How did eating fat foods (or foods from animals) impact one’s health? Are there any good effects from eating them? Any bad effects?

- Who should eat these foods? Who should avoid these foods?

- How does one’s temperament (or dominant humor) affect whether or not they should consume these foods?

- Does the information the author provides about this category of foods seem logical? Do you think it seemed reasonable at the time it was written?

- How closely do you think people followed these rules?

Analysis Questions

- Are there any clues to who may have written this text? What are those clues?

- Are there any clues to who may have read or used this text? What are those clues?

- Does anything in this source surprise you?

- What questions do you have after reading this excerpt? Where could you find answers to your questions?

Compare and Contrast the Sources

- How are the authors similar and how are they different?

- How are the sources similar and how are they different?

- Are the authors concerned with the same types of information about food and health, or are they emphasizing different things?

- Where are the authors getting their information? Are they getting it from the same or different kinds of sources?

Questions for All Sources

- Why do you think authors wrote so much about the relationship between food and health? Do you think readers followed these rules? Why or why not?

- Do you think the rules remain consistent throughout the sources? Do they seem more or less complicated, depending upon the author, date of writing, or the type of food? Why?

- Are there any similarities to modern writings and communications about food and health (including books, online articles, YouTube videos, and social media posts)?

Background

Humoral Theory

From Antiquity until around the eighteenth century, medical practitioners believed that a person’s health was determined by humoral theory. Four humors, or fluids, within a person’s body, determined how one would behave and how healthy they were. The balance (or imbalance) of blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm could explain any medical condition or behavior. A healthy individual had balanced humors, while all illnesses were thought to be caused by an imbalance in the bodily humors. Furthermore, a person was thought to possess a temperament determined by whatever humor was dominant. These temperaments were known as sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic.

The humors were associated with various properties: hot, cold, moist, and dry. These properties were also used to describe seasons, ages in the human lifespan, planets, and foods. Because foods had humoral properties, people could alter the balance of humors in their bodies by consuming individual ingredients and prepared dishes. Humoral theory, particularly the identification of properties of food, became very complicated because temperature, cooking method, and mixing ingredients could alter the properties of a food.

Diet and Social Status

Most people had a limited diet due to their social status. Rural agricultural workers, urban laborers, and the most impoverished were unable to afford a large volume or a wide variety of food. Their diets were generally limited to beans; cereals in the form of bread, gruel, and beer and ale; and very inexpensive proteins like dried and salted fish. Some vegetables might occasionally be a part of their diets. The higher up the social hierarchy a person was, the more variety in food they could afford, including different types of meats and animal products, fish, fruits and vegetables, spices, wine, etc. The wealthiest tier of society could also afford the newest and most exotic products being imported from the New World and other colonial outposts, like chocolate, pineapple, and sugar.

Books about Food and Health

During the early modern period, many texts about food and health were written and published. Some were translations or printings of medieval texts, while others were entirely new works. Many handbooks and regimens of health, like the Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum and the Tacuinum sanitatis were reproduced from medieval texts, while books describing New World plants and animals were entirely early modern works. Other types of writing combining food and health included dietaries (books about how, when, where, and what people should eat), herbals (botanical descriptions plants and also their medical and culinary uses), and collections of “sickdishes” (a part of many medieval and early modern cookbooks dedicated to food for people with difficulty eating, like the sick and invalid). Physicians, scientists, and other authors were eager to publish on the relationship between food and health, and readers readily consumed these texts. These books tended to be printed in Latin early in the period, while by the mid-sixteenth century, most published works on the topic tended to be in vernacular languages, like English, German, French, and Spanish.

Extension Activities

- Students who can safely navigate social media platforms can explore how ideas about food and health are presented in the modern world. Social media posts and videos often present concepts that are similar to views from the past. How are these presentations and ideas similar to and different from beliefs rooted in humoral theory?

- Students can connect historical ideas about food and health to actual recipes from the same period. Advanced students can peruse digitized early modern recipe books to find ties between food and health in culinary recipes and practical applications of humoral theory. Digitized recipe books in English can be found in the following collections:

- Some classroom settings may be able to accommodate the incorporation of actual food and cooking in order to bring historical ideas about food and health to life. There are many online resources to assist in the planning of classroom cooking activities. These include:

- Cooking in the Archives

- Recipes Project Teaching Recipes Series and Teaching Posts

About the Author

Sarah Peters Kernan, PhD, is a Scholar-in-Residence at the Newberry Library. Her research focuses on cookbooks and culinary activity in medieval and early modern England. She is an editor of The Recipes Project and hosts the Around the Table podcast. Sarah regularly collaborates with The Newberry Library on teaching and digital learning projects.

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the lesson “Food, Health, and the Humors in Early Modern Europe”

- Transcriptions of source excerpts used in this lesson

- Images of the sources used in this lesson (find high-resolution versions here)

- Source analysis worksheet

Related Lessons

Related Collection Essays

Additional Resources on this Topic

- Shakespeare and the Four Humors Digital Exhibition, National Library of Medicine

- “Humoral Theory,” Contagion: Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics, Harvard Library

- “The Four Humors: Eating in the Renaissance,” Folger Shakespeare Library