Introduction

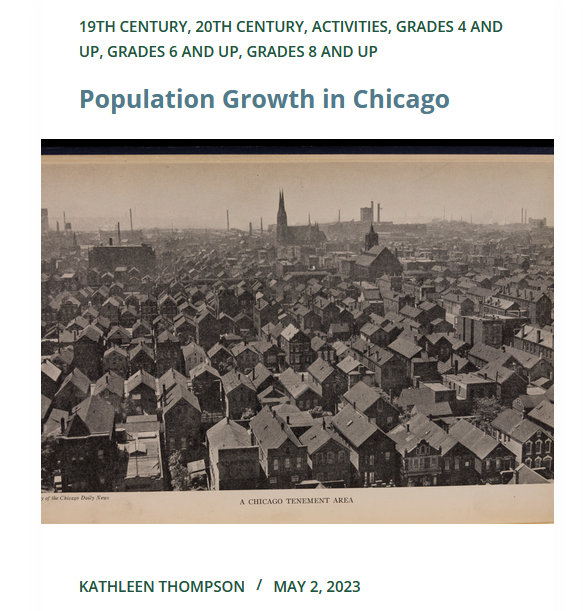

In the fifty years between the Civil War and World War I, the United States experienced a dramatic transformation. In 1870, three-quarters of the population lived in rural areas; by 1920, over half the nation lived in cities. This rapid urbanization was fueled by European immigration and the migration of rural, native-born residents who flocked to cities to work in factories. As a result, cities across the country exploded in size. Chicago’s population, for example, ballooned from just under 300,000 in 1870 to over 2.7 million in 1920. This demographic explosion brought with it a remarkable religious diversity. Catholics, Protestants, and Jews lived together in close proximity few had experienced before. Moreover, the rapid arrival of newcomers from across the globe brought new kinds of diversity to religious communities themselves. Irish Catholics, for example, not only had to learn how to coexist with European Jews and white and black Protestants from the American South and Midwest, but also with other Catholics from Italy, Poland, Hungary, and elsewhere.

Full excerpt below.

Chicago’s religious diversity posed a number of challenges. Migrants and newcomers had to consider how, if at all, their religious traditions, customs, and institutions would follow them to the city. Religious leaders and ordinary people alike worried that certain practices or communities could not survive the city’s industrial rhythms and myriad distractions. How, for example, would Sabbath observance persist in cities where business and recreation occurred seven days a week? How would churches, synagogues, and parishes thrive in new urban spaces like the vice district, immigrant ghetto, or industrial slum? How, in short, would religious communities change their inherited traditions in the midst of new surroundings?

At the moment of the city’s ascendance in American life, many observers and religious leaders claimed that urban living would destroy religious life. Some early scholars of American religious history would largely agree that cities were secular spaces that contributed to religion’s decline. More recently, however, using sources like the documents collected here, scholars have argued that the city was a space of religious innovation, rather than decay. Many of Chicago’s religious communities creatively engaged the challenges presented by urban life. Some altered or adapted existing rituals; others reaffirmed traditional beliefs in new or more fervent ways; and some generated entirely new religious ideas and practices. All, however, found ample space within the city to fashion their religious lives.

Please consider the following questions as you review documents:

- What religious ritual, practice, or belief does each document discuss? What roles do family cohesion, ethnic identity, and social morality play in these practices? How does living in the city challenge these rituals?

- How do the individuals and communities here negotiate the tensions between their religious practices and urban lives? Do they alter their traditions? Refuse to accommodate? Or do they invent new practices? What reasons do the authors here give for their decisions?

- In addition to the religious motivations behind these decisions, what role do social and economic considerations play? According to the authors, in what ways do religious practices promote or hinder economic advancement and social mobility?

- What are the relationships between religious communities and different kinds of urban space? What role does religious affiliation play in the shaping of neighborhoods or other forms of community? How does the existence of nonresidential spaces like Chicago’s downtown “Loop,” vice districts, or factory sites influence these writers?

- How do the experiences of the different religious communities covered here compare? How are their engagements with the challenges of urban life similar? Where are they unique? How, for example, does the debate among Chicago’s Jews over the Sabbath compare with Protestant concerns over evangelization? What accounts for these similarities and differences?

Brick and Mortar: Catholicism in Chicago

Catholics have long had an imprint upon Chicago’s history. The area’s first non-Native American resident was an Afro-French fur trader named Jean Baptiste Point DuSable who settled on the Chicago River in the 1790s. Catholics have also been Chicago’s largest religious community throughout much of the city’s history. Immigrants from Ireland and Germany comprised the city’s first Catholic community, establishing twenty-two “territorial” parishes in the thirty years after the Archdiocese of Chicago’s creation in 1843. These territorial parishes were open to all Catholics within a defined geographic area and thrived during Chicago’s early years. The rapid arrival of immigrants from Italy, Poland, and other parts of Southern and Eastern Europe, however, radically transformed Chicago’s Catholic communities. Finding work and preserving ethnic heritage were the most pressing concerns for these largely unskilled newcomers. Many preferred to worship and associate with their ethnic brethren. The Archdiocese responded by reluctantly allowing the formation of “national” parishes where membership was based upon one’s country of origin and not current residential location.

Selection: George Mundelein, “Address at the Dedication of the New School in St. Edmund’s Parish in Oak Park, Illinois” (1917).

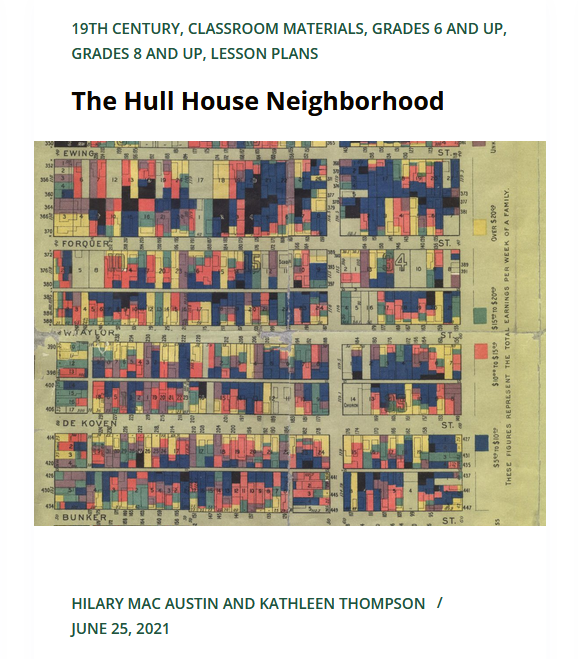

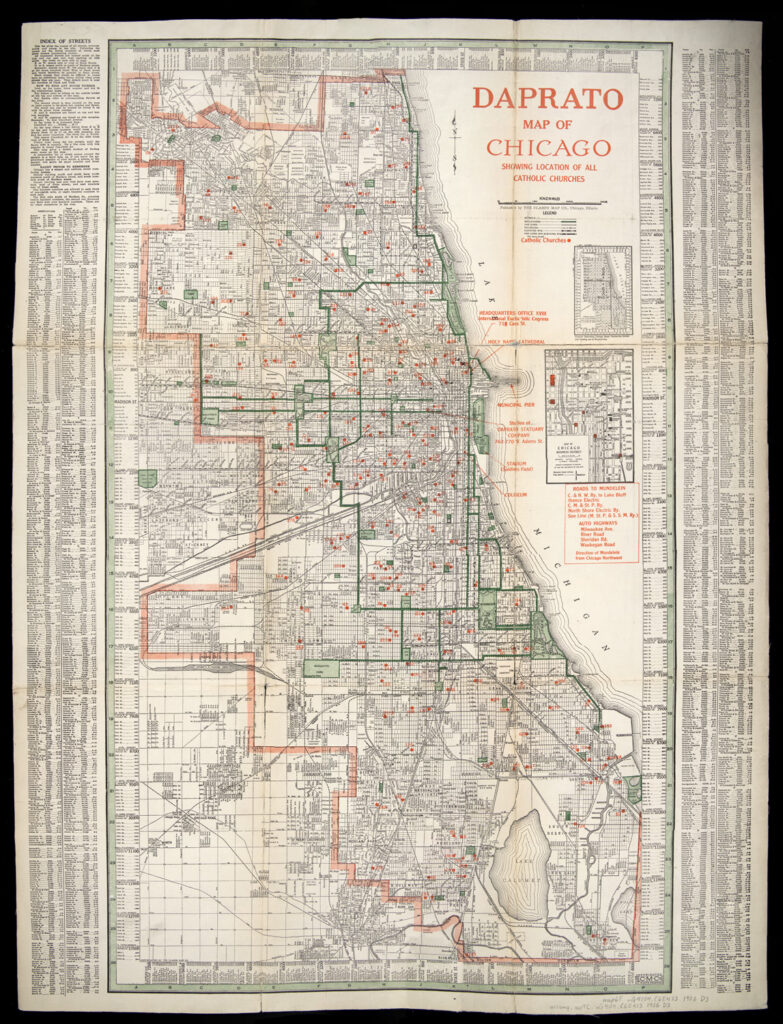

The documents here provide a glimpse into Chicago’s parish life at the turn of the century. Holy Family is the city’s second oldest Catholic Church, organized as a territorial parish in 1857 on Chicago’s near West Side. St. Boniface parish, on the other hand, was from its founding in 1862 a church for German immigrants staffed by German priests. The Daprato map, published by the Archdioceses to celebrate its hosting of the 1926 International Eucharistic Congress, continues to underscore the ethnic nature of Catholicism in Chicago. Meanwhile, the address by Cardinal George Mundelein (1872–1939), Archbishop of Chicago from 1915 through 1939, reveals some of the tensions that existed between old immigrants who ran Chicago’s Archdiocese and the new immigrants who filled the churches. An American-born son of German immigrants, Mundelein argued that parishes should be places where immigrants adopt their new identities as American, not reaffirm their foreignness. Throughout his tenure as Archbishop of Chicago, Mundelein would lead a campaign to return to territorial parishes over national ones. His efforts had decidedly mixed results.

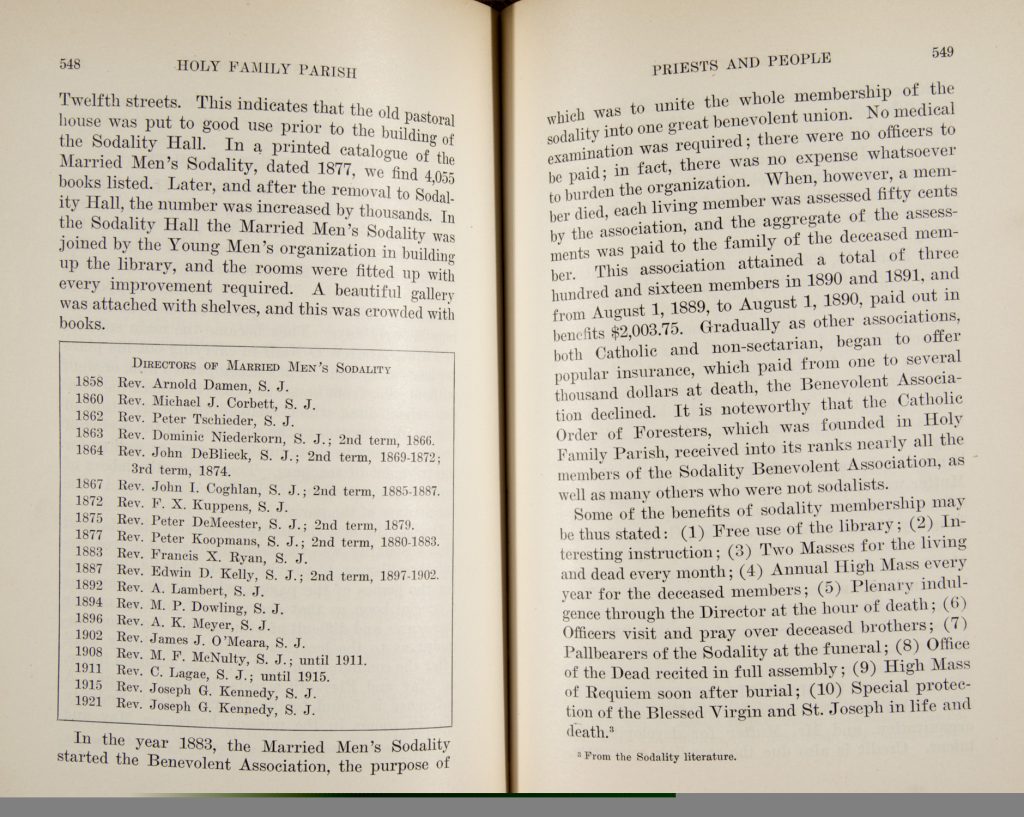

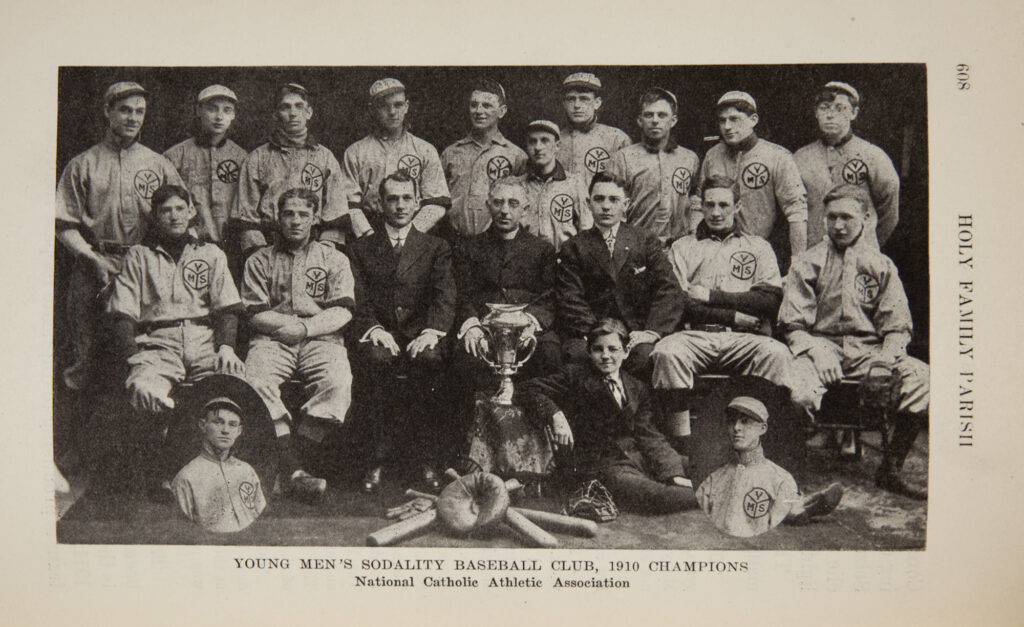

Selection: Thomas Mulkerins, “Married Men’s Sodality” and “Young Men’s Sodality Baseball Club” in Holy Family Parish Chicago: Priests and People (1923).

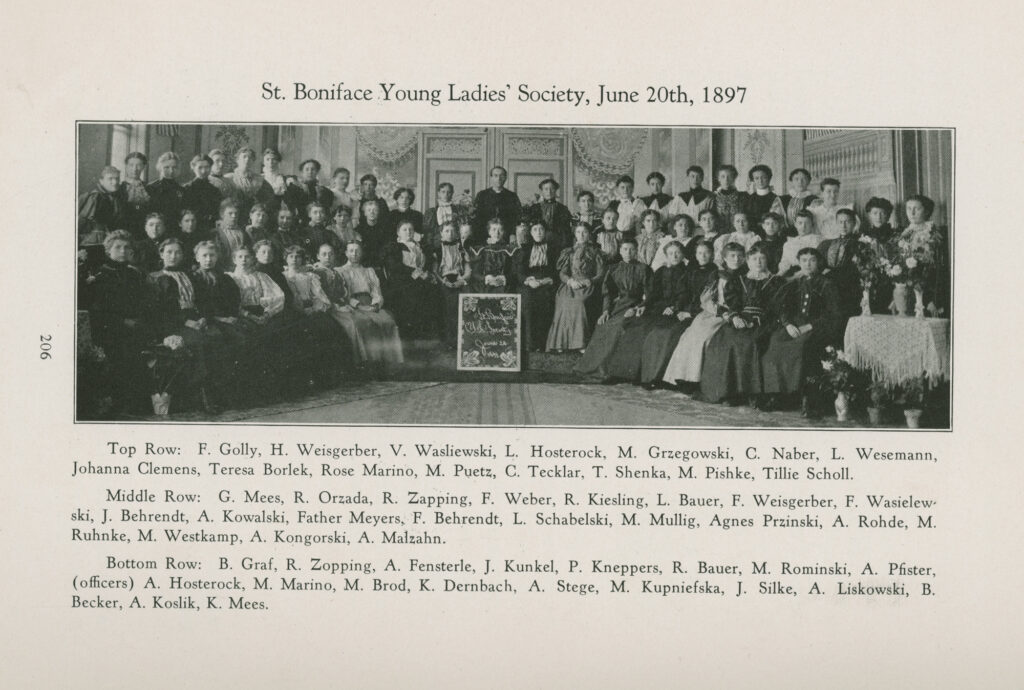

Selection: F. L. Kalveage, “The Young Ladies’ Sodality” and “St. Boniface Young Ladies’ Society” in The Annals of St. Boniface Parish (1926).

Questions to consider:

- What is the relationship between parish life and the preservation of ethnic culture?

- On the Daprato map, how do ethnicity, community, and religiosity overlap?

- Describe the activities and objectives of the sodalities, or devotional societies, described in Holy Family and St. Boniface’s parish histories. What are their religious purposes? What are their social roles? How do the men and women’s sodalities differ?

- According to Mundelein, what is the parish school’s role in American Catholic life?

- What role does economic advancement and social mobility play in the functioning of the parish school and sodality?

A Chosen People in a Strange Land: Chicago’s Jewish Communities

Jewish immigrants from German lands established an institutional presence in Chicago during the 1840s. It was the influx of immigrants from Eastern Europe between 1881 and 1924, however, that transformed the Jewish population of Chicago. By the early 1930s, Chicago had the third largest Jewish population of any city in the world, trailing only New York and Warsaw. Questions surrounding Jews’ acculturation to the rapidly growing city preoccupied Jewish communities. These three sources—a sermon by a rabbi, a memoir by a Jewish immigrant, and woodcut illustrations by an immigrant published in an important sociological analysis of Jewish Chicago—speak to a range of concerns about how Jewish traditions and customs might endure amid pressures to assimilate. In particular, the fact that the Jewish Sabbath (beginning Friday at sundown and ending Saturday at sundown) does not coincide with the more widely recognized Christian Sabbath on Sunday caused particular stresses to Jews both as individuals and as communities. The issues that arose around conflicting Sabbaths were not only religious in nature but also social and economic.

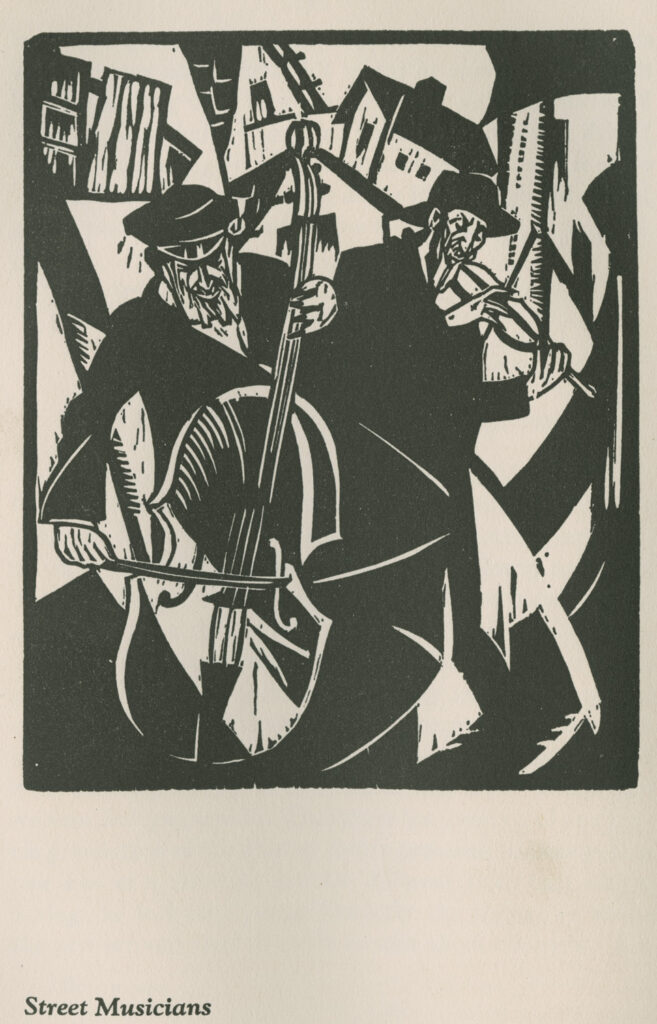

Selection: Todros Geller, Yiddish Life woodcuts: “Talmudic Student,” “Street Musicians,” “Maxwell Street,” and “Horseradish Grinder” (1928).

Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch (1852–1923) led Chicago’s Sinai Congregation (Reform) from 1880 through 1923. A national figure because of his particularly dynamic pulpit orations, Hirsch put Sinai at the cutting edge of Reform Judaism and argued that rituals and practices had to adapt to fit modern circumstances. Indeed, Sinai’s policies on observing the Sabbath were seen as radical even within Reform Jewish circles. Hilda Satt Polachek (1882–1967) emigrated from Poland to Chicago in 1892. She took classes at Hull-House as a child and maintained an association there as an adult, teaching classes and giving tours. She remained active in social reform causes throughout her life and published poetry, plays, essays, and this memoir I Came a Stranger: The Story of a Hull-House Girl. Todros Geller (1899–1949) emigrated from Ukraine to Canada in 1906. By 1918, he had settled in Chicago as an artist. His popular portfolio of woodcuts, titled Yiddish Life, appeared first in 1926 and were included in University of Chicago sociologist Louis Wirth’s influential 1928 book, The Ghetto. His work provides a glimpse into the world of Orthodox Jews, who were generally less willing to alter their ritual practices.

Selection: Emil G. Hirsch, “Address by Dr. E. G. Hirsch” in Report of the services in commemoration of twenty-fifth anniversary of the introduction of Sunday services in Chicago Sinai Congregation January 15, 1899, 9-14 (1899).

Questions to consider:

- How does Rabbi Hirsch reconcile the fact that “the Sabbath idea is cardinal to Judaism” with his desire to adapt Sabbath practices?

- Rabbi Hirsch often mentions Jews’ “mission” in this sermon. What did he want his audience to understand about Jews’ mission? How does this concept of mission illuminate Hirsch’s thoughts about religious pluralism in America? (It may help to know that Jews traditionally do not believe in proselytizing.)

- How do labor and religious practice become intertwined in Jewish immigrants’ lives, according to Polachek? Would Rabbi Hirsch and Polachek’s father agree on the limits of Jewish assimilation?

- How do Geller’s woodcuts depict Jewish individuals and Jewish communities? What information do these woodcuts convey about labor, commerce, and religion in modern urban cities?

To Save the City: Protestant Responses to Urbanization

At the turn of the twentieth century, the majority of Chicago’s Protestants were broadly evangelical in nature. With the exception of Lutherans who hailed from Germany and Scandinavia, most were white, native-born migrants from New England and the Midwest. Their religious beliefs were forged in the revivals of First and Second Great Awakenings. Despite their denominational differences, Methodist, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Baptist churches alike all agreed upon certain essential doctrines such as a belief in the Bible’s divine origins. Paramount, however, was a belief that it was the duty of every Protestant Christian to evangelize, or proselytize, nonbelievers to their faith. Through church activity and mission work, evangelical Protestants hoped that the Gospel message, or the story of Jesus as recorded in the Bible, would convert the world.

Chicago’s demographic, cultural, and religious transformation at the turn of the century posed a number of challenges to this evangelical mission. The city’s ethnic diversity made communication, much less evangelization, difficult for native-born Protestant ministers. Even more challenging were the social conditions in some parts of the city. Some ministers argued that the overcrowded, industrial neighborhoods where many immigrants lived were not conducive to the establishment of Protestant churches. Others found the concentration of saloons and brothels in vice districts such as the city’s notorious “Levee” an affront to Protestant moral standards.

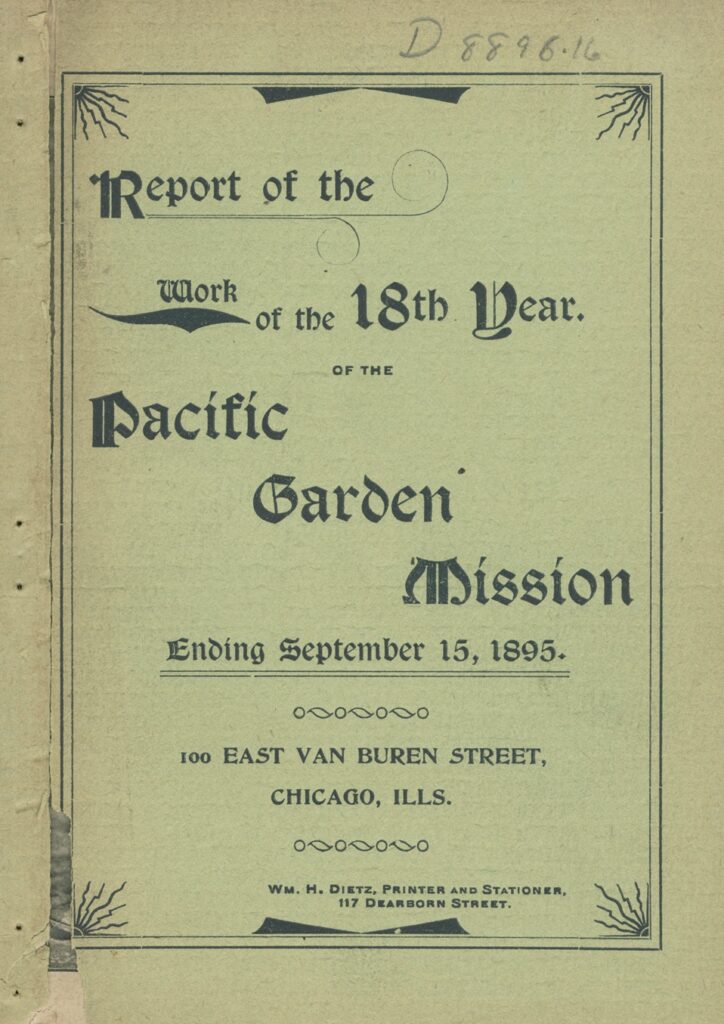

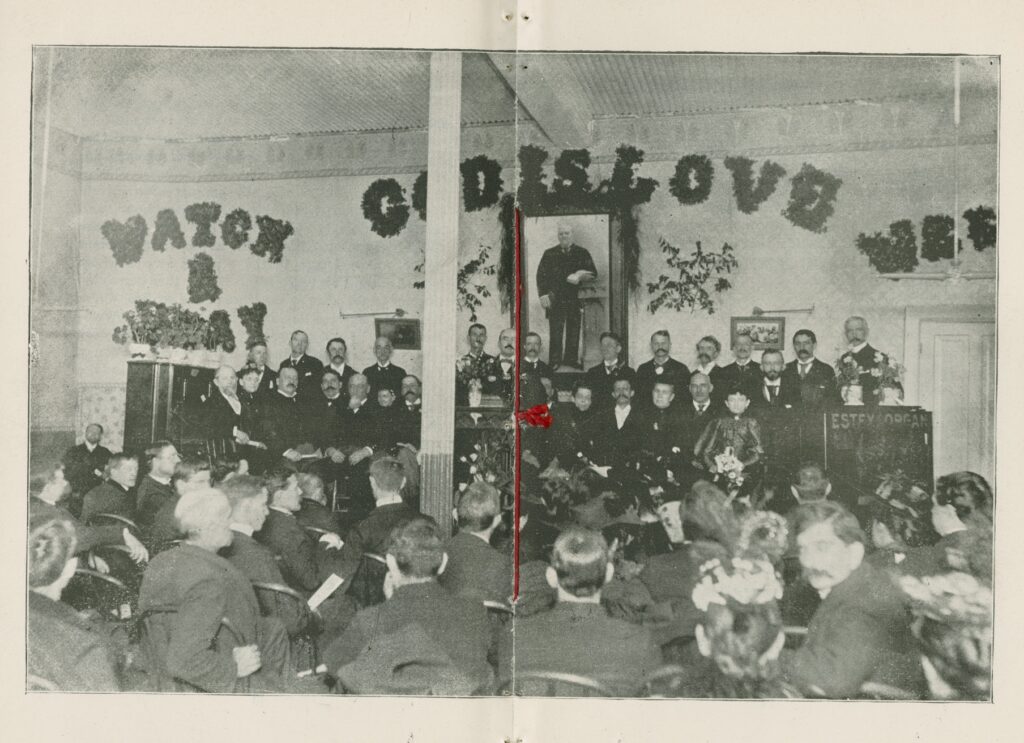

Selection: Pacific Garden Mission, Report of the Work of the Eighteenth Year of the Pacific Garden Mission Ending September 15th, 1895 (1895).

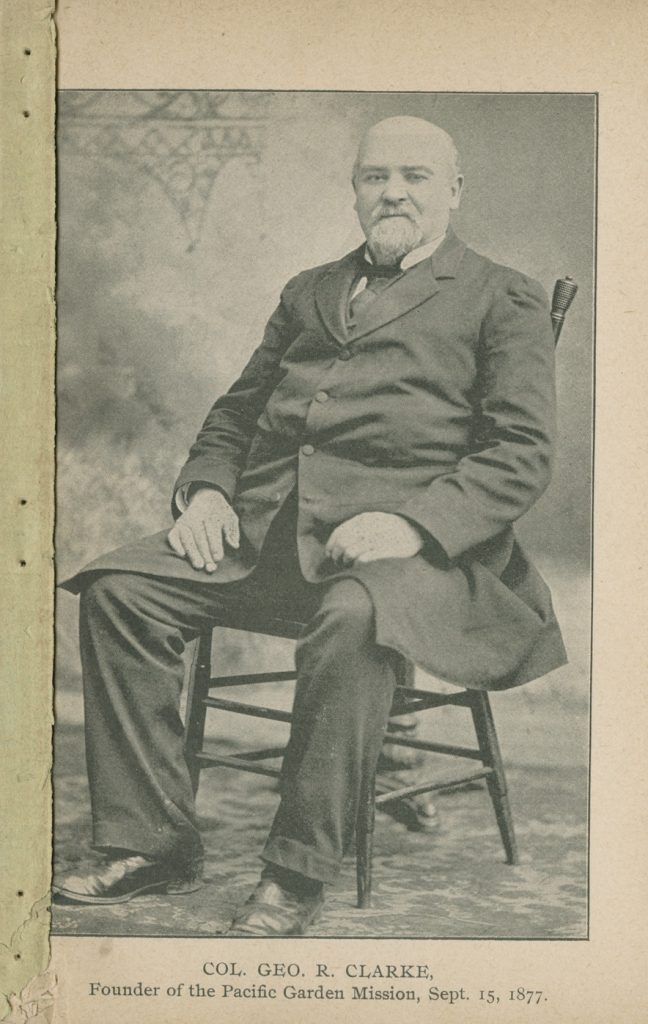

The documents here represent two differing responses to the difficulties of urban evangelization. Real estate speculator and Civil War veteran George Clarke (1827–1892) founded the Pacific Garden Mission with his wife Sarah in 1877 in an attempt to convert the visitors of Chicago’s Levee district. The Mission’s name was derived from the saloon where it was first located, the Pacific Beer Garden, and reflected Clarke’s desire to take over the Levee for Jesus. In contrast, Chicago Theological Seminary professor Graham Taylor (1851–1938) took a different approach. Taylor was at the forefront of the Social Gospel movement, which sought to address not only people’s spiritual but also their material conditions. A friend and admirer of Jane Addams and Hull House, Taylor founded the Chicago Commons settlement house in 1894 as an extension of his mission work.

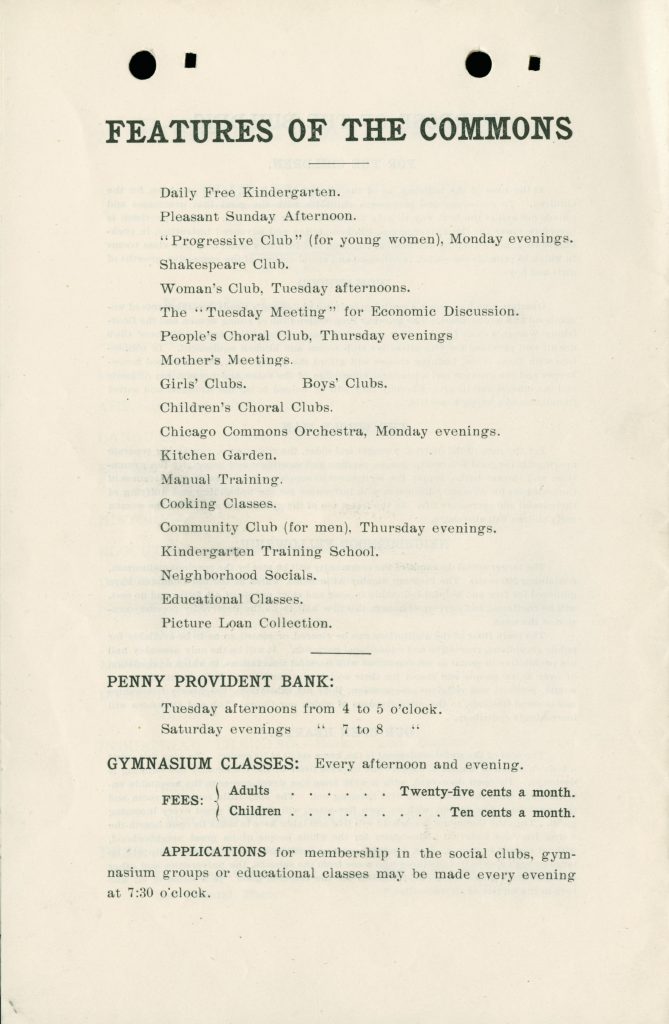

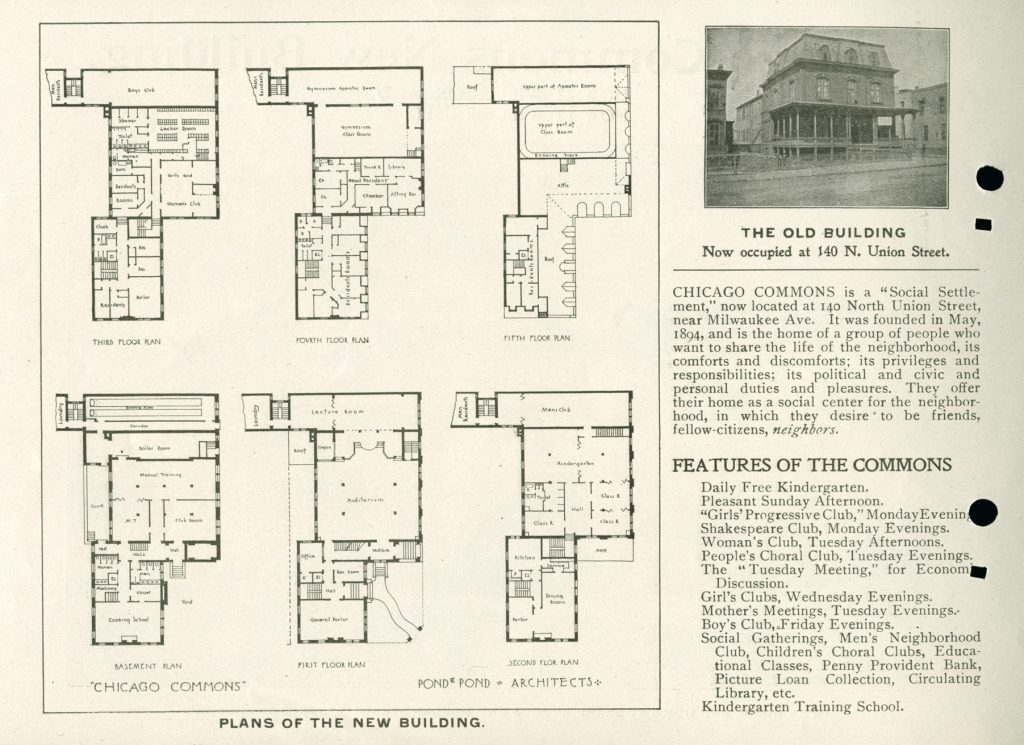

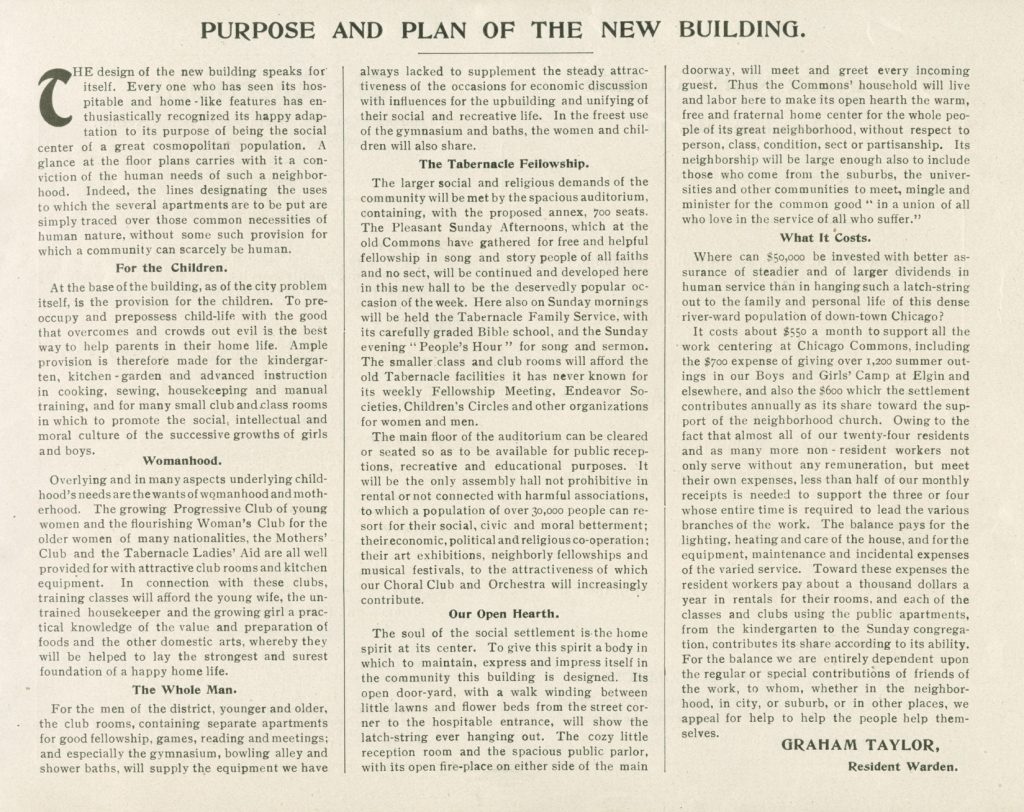

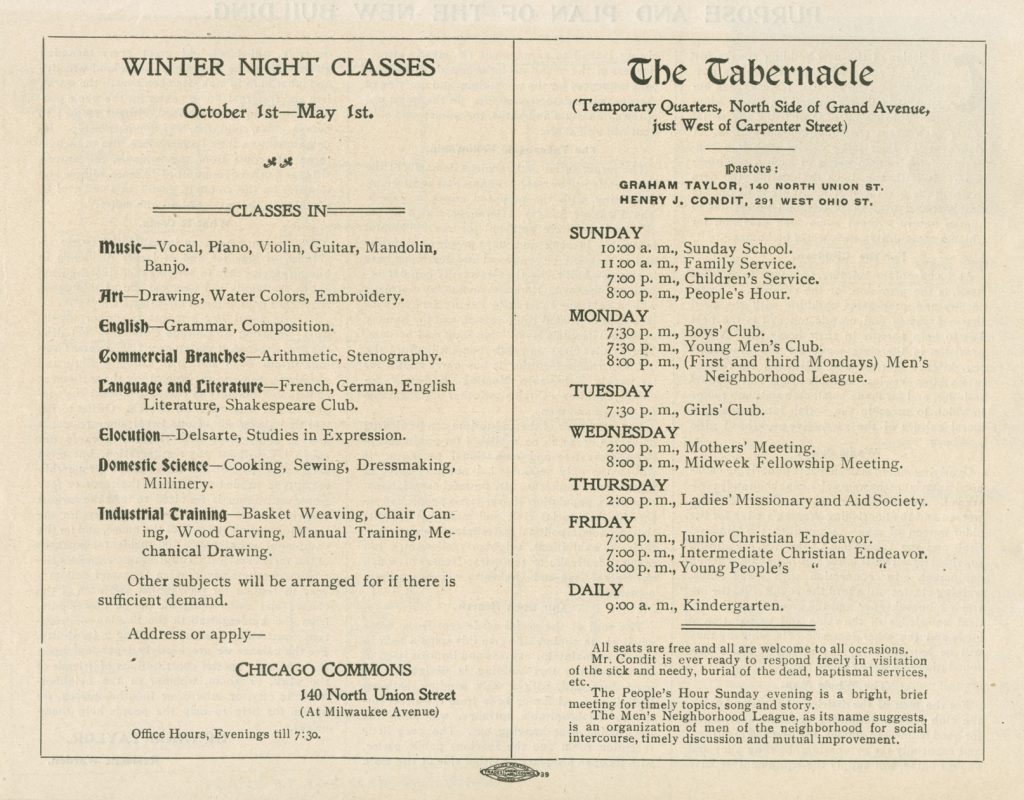

Selection: “What is Chicago Commons?” and “Chicago Commons New Building”

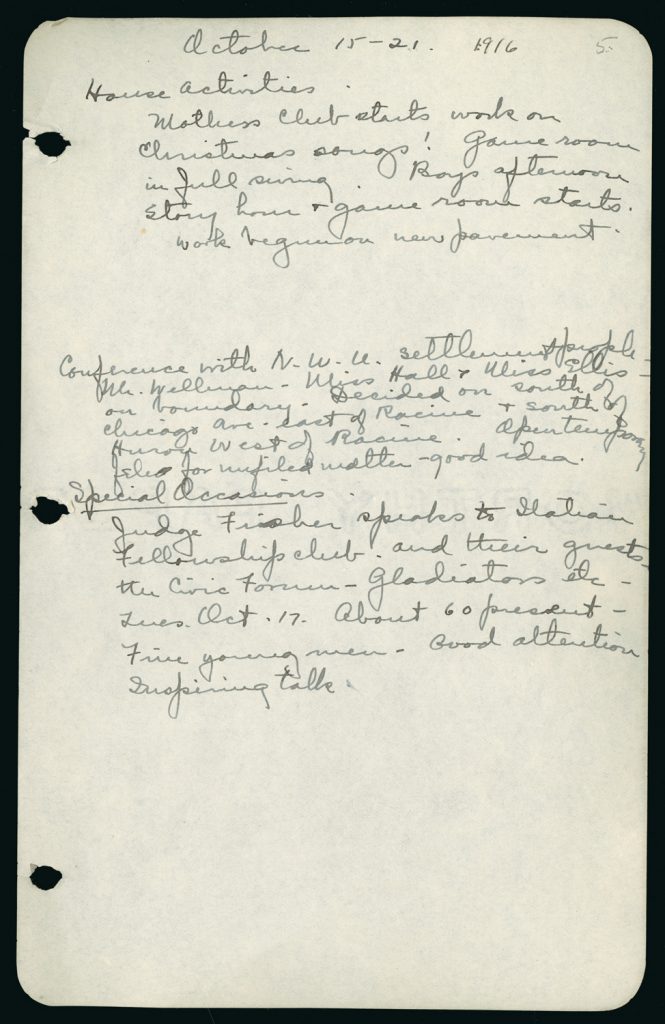

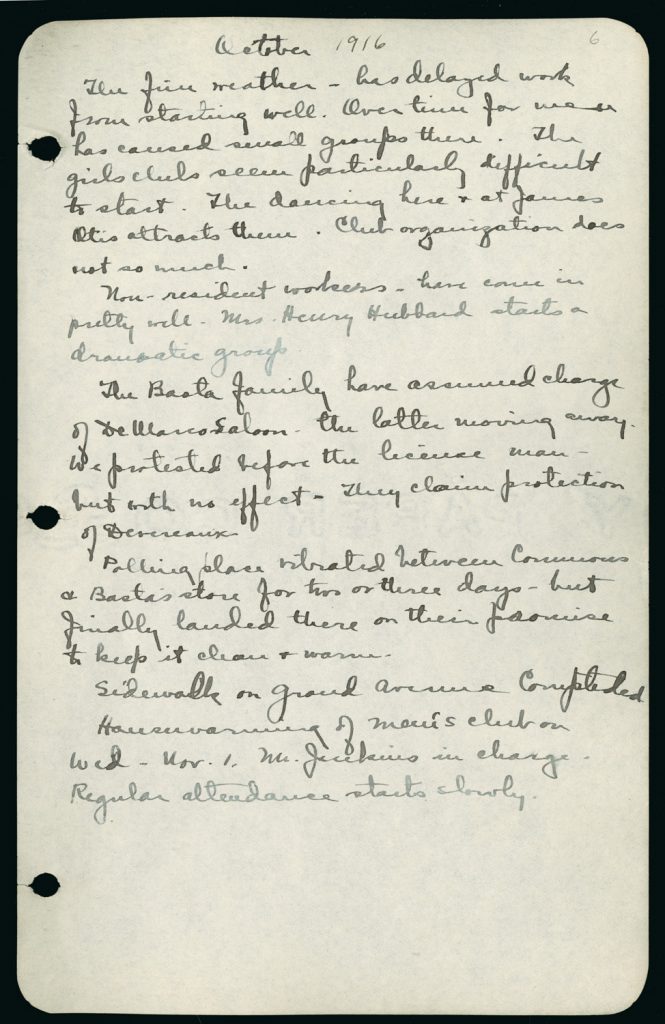

Selection: Graham Taylor, “Report for October 1916” (1916).

Questions to Consider:

- What are Clarke’s opinions about Chicago’s social life? Is Chicago a fundamentally religious place? If not, what are the sources of the city’s spiritual depravity? What potential solutions to Chicago’s supposedly “sinful” condition does Clarke see?

- Clarke claims that the Pacific Garden Mission has provided a blueprint for reaching Chicago’s unchurched “masses.” What are the Pacific Garden Mission’s primary activities that, as he says, bring the lost “under the sound of the Gospel”?

- Based on the Chicago Common’s October 1916 monthly report, what are its main activities? What do these activities convey about Taylor’s understanding of Chicago’s social and religious challenges? What do the documents from the Commons reveal about Taylor’s proposed solutions?

- Compare and contrast the photograph of the Pacific Garden Mission’s interior with the pamphlet announcing the Chicago Commons’ new structure. What do the differences in these two physical spaces say about the organizations’ different approaches to Chicago’s religious challenges?