Introduction

The Great Migration that occurred in the United States during the twentieth century marks one of the most important social movements in American History. The relocation of millions of Black southerners was ignited by a grassroots desire to improve the life chances of those who struggled to make headway under America’s notoriously racist power structure. As the largest internal migration to take place in the United States, the Great Migration forever altered the American landscape.

Like other racial and ethnic groups who moved to the United States, Black America’s internal migration assumed spiritual import, reflected in the various ways African Americans characterized their movement, such as “Flight out of Egypt,” “Going into Canaan,” and a quest for “The Promised Land.” Black migration occurred in several waves. The largest exodus spanned the years 1910-1970. During this time, between five and six million African Americans journeyed from the South to other regions of the country. The decision to abandon the lands they had known for generations did not come easy, but nevertheless resulted in vast political, economic, and cultural shifts that defined American life for decades to come. This essay details the experiences of African Americans during the Great Migration: their motivations, their life upon arrival in various cities, and the challenges they faced. The essay concludes with a brief discussion of the Great Migration’s immediate impacts and enduring legacy.

A People in Motion: The Roots of Migration

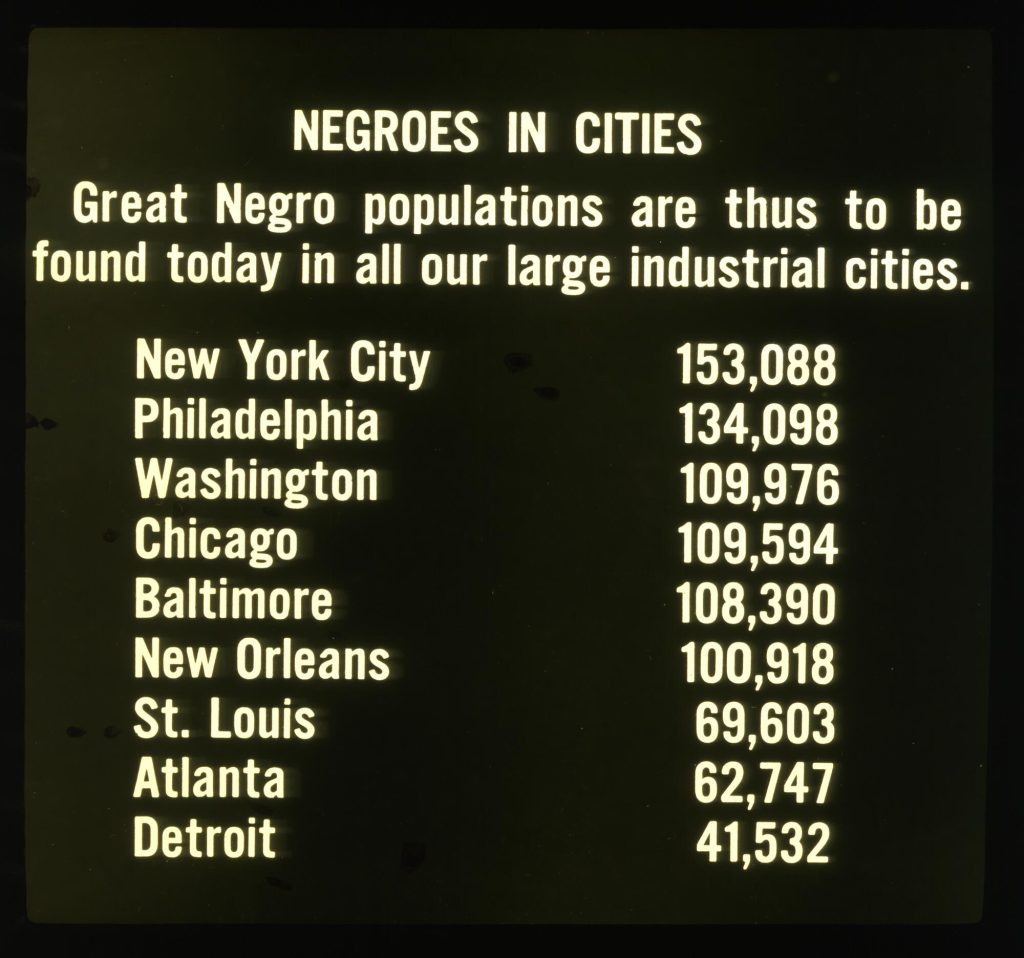

Before the Great Migration, it was safe to conclude that African Americans were primarily a southern people. In 1910, approximately ninety percent of all African Americans resided in the South, including in Alabama, Tennessee, Florida, Georgia, the two Carolinas, Mississippi, and other areas of the Deep South. However, by 1970, only about fifty percent of all African Americans called the South home. The majority lived in urban areas. “The First Great Migration” occurred in the decades surrounding World War I (1914-1918). During this time, large concentrations of African Americans moved to Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York, and other cities. During “The Second Great Migration,” which World War II (1941-1945) helped facilitate, African Americans also landed in far greater numbers in western cities and states, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, and Seattle.

Although the bulk of the Great Migration occurred between 1910-1970, African Americans have always been a people in motion. Arguably, the seeds for relocation were sown much earlier in US history, as a result of involuntary movement. Unlike many European, Asian, and other immigrant groups who looked to North America as a sanctuary from political and economic oppression, African Americans endured the brutality of the “Middle Passage.” The Middle Passage refers to the treacherous voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, which occurred on tightly-packed, disease-ridden ships and killed millions. During the sixteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries, European slave traders kidnapped Black people from the African continent and carried them to distant and unfamiliar shores in Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean, and North America. African Americans continuously battled against their perpetual captivity. They engaged in daily acts of resistance, including refusing to work and running away. Escaping the jaws of slavery, many joined newly founded free Black communities on either side of the Mason- Dixon line.

Emancipation did not stem movement. Upon securing their freedom in 1865, African Americans travelled about the country, often in search of kin, but also for want of opportunity. Some of the earliest post-Emancipation migrations carried African Americans to Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, Kansas, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. The late nineteenth century also met with trickles of movement out of the rural South, establishing African Americans in Birmingham, Atlanta, Houston, Memphis, and other southern cities. This preliminary relocation to the South’s urban areas acquainted African Americans with wage-earning and the demands of city living. Historian Carole Marks argues that those who flooded northern cities in subsequent years were mostly urban, non-agricultural workers, although other scholars disagree with some of her empirical claims. Nevertheless, these intraregional migrations invariably set in motion a process of urbanization that endured for another century.

Questions to Consider:

- What was the Great Migration? Describe its various waves.

- List examples of some of departure points of African American migrations, as well as their destinations. If possible, mark those places on a map.

- Looking at the list of places from Question 2, what do you think the term “intraregional migration” means? (If you need help, break down the component words in “intraregional.”) How did intraregional migration differ from the forced migration of the Middle Passage? Try to determine how these large-scale intraregional migrations might have influenced Black migrants’ decisions to move to certain places throughout the country.

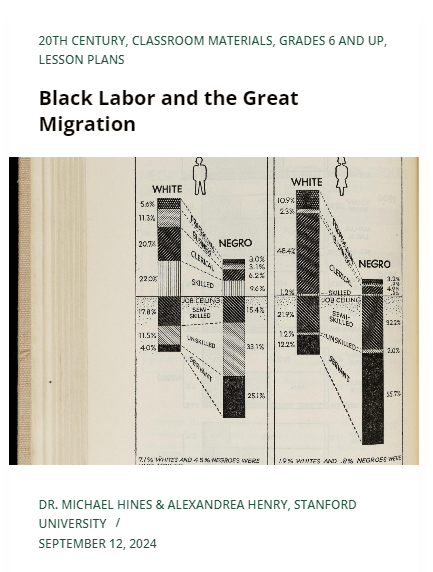

- Use the image above to draw some conclusions about intraregional migrations. Does anything in the image stand out? Why?

Motivations

In the past, scholars of the Great Migration characterized African American’s motivations in terms of “push” and “pull” factors. This framing emphasizes uncontrollable circumstances and the influence of outside agents, such as labor recruiters. Scholars continue to debate the myriad reasons for African Americans’ seemingly permanent departure from the South, however. Many now emphasize the importance of personal choice and agency.

Undoubtedly, external circumstances fueled Black Migration, including economic hardship. Prior to 1910, most Black southerners labored as underpaid or unpaid domestic servants, tenant farmers, and sharecroppers. As a result, many African American families fell victim to various forms of economic exploitation, including peonage. Peonage, sometimes called debt slavery or debt servitude, required individuals to pay off their debts by working when they proved unable to offer cash payments. Falling into peonage forced many African Americans to work for former and once aspiring slaveholders and created cycles of poverty that were almost impossible to break.

An ongoing series of natural disasters also plagued the region. Extensive flooding along the Mississippi River and the boll weevil epidemic nearly obliterated the South’s cotton industry. Consequently, African Americans struggled to gain a foothold in the southern economy. On February 10, 1917, one Charleston, S.C. resident remarked in a letter to the New York Age, a Black newspaper, “As I am from the south and it is an average difficulty for a southern to endure the cold without being climate. If is posiable [sic] for you to get any other job for me regardless to its nature just since the work is indoor [sic] I’ll appreciate the same.” The man shuddered at the thought of working in the cold, but New York City’s favorable economic conditions trumped the South’s favorable weather conditions. “As s it is understood [sic] the times in the south is very hard and one can scarcely live,” the man added.

In addition to economic factors, political conditions fueled the Great Migration. Despite their best efforts to obtain equal political rights during the antebellum Period, African Americans held no rights as citizens of the Republic prior to the Civil War. Beginning with Radical Reconstruction in 1865, African Americans’ protracted battle for political recognition yielded the Thirteenth Amendment, which prohibited “involuntary servitude”; the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship rights and equal protection under the law for “all persons born or naturalized in the United States”; and the Fifteenth Amendment, which constitutionalized Black men’s voting rights. However, the Compromise of 1877 and the end of Radical Reconstruction resulted in an abrogation of African Americans’ new political rights and catapulted African Americans back into subservience.

Embittered by the South’s war losses and Black civil rights gains, ex-Confederates stripped away Black men’s right to vote. The southern states also enacted, with lightning speed, a series of ordinances that guaranteed Black disenfranchisement. African Americans became subject to literacy tests, poll taxes, and the grandfather clause, which tied eligibility for voting to one’s grandfather’s voting rights status. In various southern states, lawmakers also thwarted Black male suffrage by limiting voting to white men during primary elections. This practice, also known as the white primary, remained in effect until the Supreme Court ruled against it in Smith v. Allright in 1944. Additionally, many states barred African Americans from jury service and from testifying in court. By and large, Black southerners were shut out of the political process, providing them with yet another reason to head north.

Social conditions also sped individual and collective decisions to relocate. Many of these conditions were part of Jim Crow, a system of living that relegated whites and Blacks to largely separate worlds with unequal resources. Jim Crow’s introduction in the South was part of a concerted effort among white citizens to reclaim their perceived superior status within the American social order. Holding fast to the theory of racial separation, white southerners concocted various laws and practices that forced racial segregation in transportation, lodging and accommodation, recreation, and schools. Additionally, vagrancy laws, which targeted unemployed Blacks, served as direct pipelines to prison. Many African American women, men, and children labored as part of the South’s convict leasing and chain gang systems. In 1896, the Supreme Court codified these racist practices in Plessy v. Ferguson, which legalized “separate but equal” in the states. African Americans suffered greatly under these conditions. As one woman from Mobile, Alabama remarked on April 25, 1917, “I am the mother of 8 children [sic] 25 years old and I want to get out of this dog hold.” In her correspondence, which was among a series of letters journalist Emmett Scott documented in Negro Migration During the War, she insisted, “I don’t know what I’m raising them in this place [sic] and I want to get to Chicago where I know they will be raised an [sic] my husband crazy to get there.”

Significantly, many African Americans opted for racial separation as a method of self-determination and protection. Others insisted that segregation contradicted the concept of democracy. The South’s segregated school system especially troubled African Americans who prized education as a citizenship right. In fact, the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier—Black newspapers that provided information and inspiration for the Great Migration—reveal how the desire for quality education served as a dominant factor in the Black exodus from the South. It is true that African Americans galvanized the universal education movement in the South, as Heather Andrea Williams and several other scholars note. A number gained a quality education in the schools they and white missionaries founded during the nineteenth century. However, adequate educational resources remained out of grasp for the majority. White southerners refused to dedicate ample funding towards Black schools. For example, as the legal scholar Mark Tushnet observes, during the late 1920s, the per pupil expenditures for education in Georgia was $36.29 for whites and $4.59 for Blacks. In South Carolina, school officials spent $36.10 for white students and $4.17 for Black students. These disparities resulted in the use of outdated curriculum, abbreviated school terms, and the instruction of multiple grade levels under a single teacher. Some localities lacked Black schools altogether. Disparities also existed at the level of higher education, providing yet another reason for African Americans to migrate, as Crystal R. Sanders argues in her book, A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners, Segregation Scholarships, and the Debt Owed to Public HBCUs.

Efforts to escape the ever-present threat of racial violence were just as important to Black southerners’ decisions to migrate as the desire for improved educational opportunities and the quest for economic and political power. Anti-Black violence riddled the post-Reconstruction era. While present in the northern states, it was especially pervasive in the South. The Compromise of 1877 handed the presidency to Rutherford B. Hays in exchange for ending Reconstruction and removed Union troops from the former Confederacy. These troops were often the only force protecting Black political rights and African Americans’ very safety. Thereafter, racist southerners deployed the most diabolical means to constrain Black mobility, including lynching, or the execution and often publicized murder of individuals without the due process of law. In their efforts to justify numerous lynchings, white southerners falsely accused African Americans of criminal behavior. These claims, which included sexual assault allegations, built upon centuries of racist stereotypes of Black men as criminal, violent, and sub-human. However, as the suffragist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett revealed through her courageous investigations, “lynching bees” victimized any Black man, woman, or child who dared to challenge the South’s prescribed racial order.

Between the early 1880s and the late 1960s, lynch mobs enacted a wave of terrorism that resulted in massive property loss and more than four thousand known murders. Comprised of everyday white people, including clergymen and women, lynch mobs frequently collaborated with law enforcement, white political officials, and “the untruthful white press,” as Wells-Barnett asserted in 1892 in Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. Such violent social conditions placed a premium on the acquisition of political and legal rights among African Americans. Meanwhile, the hypocrisy imbedded in lynch mobs’ justifications for murdering Black citizens grew more evident. As Wells-Barnett observed, Reconstruction had done little to alter white men’s claims to near-complete access to Black women’s bodies. Not surprisingly, the threat of rape by white men also influenced families’ decisions to migrate out of the South.

The specter of violence further exposed the South as a socially inhospitable place for African Americans. Yet, as much as white southerners rejected Black attempts to achieve social mobility, many opposed the surging exodus. Corresponding with Opportunity Magazine in 1924, an organ of the National Urban League, one white Atlanta businessman insisted, “I unhesitatingly assert that the prosperity of Georgia depends upon keeping the Negro here.” Additionally, some states passed laws to prevent Black migration and fined labor agents who endeavored to recruit Black workers. Several railroad companies even refused to sell tickets to prospective migrants. As Malaika Adero writes, “white southern society displayed a kind of possessiveness towards Blacks after slavery was abolished. Southern Whites didn’t want their negroes to stay and live as equals, succeeding in life on their own terms, but nor did they want them to leave.”

Whites were not the only ones to oppose Black migration out of the South. For example, Booker T. Washington argued that, as the southern economy evolved, African Americans must stay and avail themselves of opportunities for land ownership, entrepreneurship, and institution-building. A former slave, the founder of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, and a leading authority in race matters at the turn of the twentieth century, Washington extolled the value of economic self-sufficiency among southern Blacks. Many critiques of Washington have emphasized his theory of accommodationism, or his willingness to prioritize financial gain over political rights. Washington laid out his position in his famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech in 1895, which predated the Plessy “separate but equal” ruling by a year. However, Washington’s insistence upon Black self-determination and economic development foretold various challenges African Americans faced upon relocation to northern cities that were anything but economic oases.

The varying hardships African Americans faced, or what some might refer to as “push” factors, influenced individual and collective decisions to migrate. Push factors combined with the prospect of economic opportunity and improved social conditions, or the north’s “pull factors,” to excite movement out of the South. “I’ll never work in nobody’s kitchen but my own anymore,” expressed one migrant woman in a study conducted by The Chicago Commission on Race Relations. “No indeed! That’s the one thing that makes me stick to this [factory] job. You do have some time to call your own.” More than anything, it was a sense of agency, or the right to determine one’s own destiny, that operated as a bulwark for the Great Migration.

Questions to Consider:

- What were the various motivations that influenced African Americans’ decisions to migrate out of the South? What additional reasons do the primary sources reveal about their motivations?

- Specifically, describe how violence factored into the decision to migrate.

- Why did some white southerners oppose Black migration? What steps did they take to prevent migration?

- Why did Booker T. Washington oppose Black migration?

“The Negro in the City”

For nearly three centuries, the majority of African American called the South home. But for the millions who beelined out the region, the gains seemed to outweigh the losses. “I don’t have to master every little white boy comes along,” one Philadelphia migrant wrote. “I haven’t heard a white man call a colored [person] a n— since I been in the state of PA. I can ride the electric street and steam cars where I get a seat,” the Philadelphia migrant added.

The advent of war in the twentieth century offered unprecedented employment opportunities for African Americans. World War I (1914-1918) fueled the demand for workers in northern industries, including steel, oil, coal, rubber, meatpacking, the stockyards, and the railroad and automobile sectors. World War II (1941-1945) and the expansion of the military industrial complex created opportunities in the West, especially in Oakland, San Franciso, and Los Angeles. Labor agents actively recruited Black workers to fill “cheap labor” shortages. Labor shortages in these urban centers resulted primarily from the vast numbers of white men who joined the war effort, abandoning jobs that previously excluded African Americans. Additionally, a heightened sense of nativism and xenophobic legislation contributed to a decline in European and Asian immigration. Working for the defense industries, African Americans eagerly anticipated the prospect of higher and more consistent wages, however.

The opening of industrial jobs yielded uneven results for Black men and Black women, impacting migration patterns along gendered lines. While men experienced noticeable gains in the war industries during the early twentieth century, most women continued to toil in domestic service. It is likely for this reason, some historians argue, that men were twice as likely to relocate than women, although many moved with the expectation that they would send for women and girls at a later date. By World War II, married couples were more likely to migrate together. Much of this was due to the increasing availability of jobs for women during World War II. With the doors of industry opening, African American women abandoned domestic service positions in droves. Immigrant women from Latin America and the Caribbean subsequently filled these positions, contributing to the diversity of Black communities, as several transnational scholars who study Black diasporic migrations to the United States observe.

To facilitate their transition to city life, migrants counted upon family and the services of labor agents. Virtually functioning as community centers, churches also played a fundamental role in providing safe spaces for newly arrived migrants to become acquainted with the nuances of city living. Churches offered a wide range of social services for men, women, and children, including labor education and employment assistance. Additionally, churches furnished opportunities for more established African Americans to monitor migrant behavior, revealing, in many ways, the class divide that existed between the “old settlers” and the newcomers. As Wallace Best argues, however, Black religious experiences were mutually reinforcing processes. Migrants also helped transform the character of Black spiritual practices in urban areas.

In addition to churches, migrants drew upon the many networks and autonomous institutions that Black communities established. Founded in 1911, for instance, the National Urban League offered guidance on employment, housing, and health services. The various Urban Lague branches operated much like the settlement houses established by white social reformers, who directed their attention towards European immigrants and excluded African Americans from their programs. Black women also worked under the auspices of the Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), formed in 1909 by several Black leaders, including W.E.B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells-Barnett, along with several progressive whites. Much of Black women’s social reform efforts originated with the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which counted hundreds of branches across the United States. The NACW provided a wide range of social services for African Americans, including daycare.

The Great Migration also resulted in major political shifts among African Americans, inspiring a sense of racial solidarity and commitment to expanding social justice movements. As historian Donna Murch points out, Black political assertiveness originated with many migrants prior to their relocation to northern cities, which in many ways laid the foundation for the modern Civil Rights movement. However, African Americans’ militancy grew more visible as part of the “New Negro Movement” that enveloped American cities after World War I. With its flagship branch located in New York City and satellite groups sprawled throughout the world, the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), led by Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, played a major role in African Americans’ shifting political consciousness. Garvey promoted the idea that Blackness was synonymous with greatness, which offered a direct challenge to scientific racism and prevailing theories regarding Black inferiority. The UNIA leader also launched many businesses as part of his emphasis on Black self-determination and Black economic self-sufficiency.

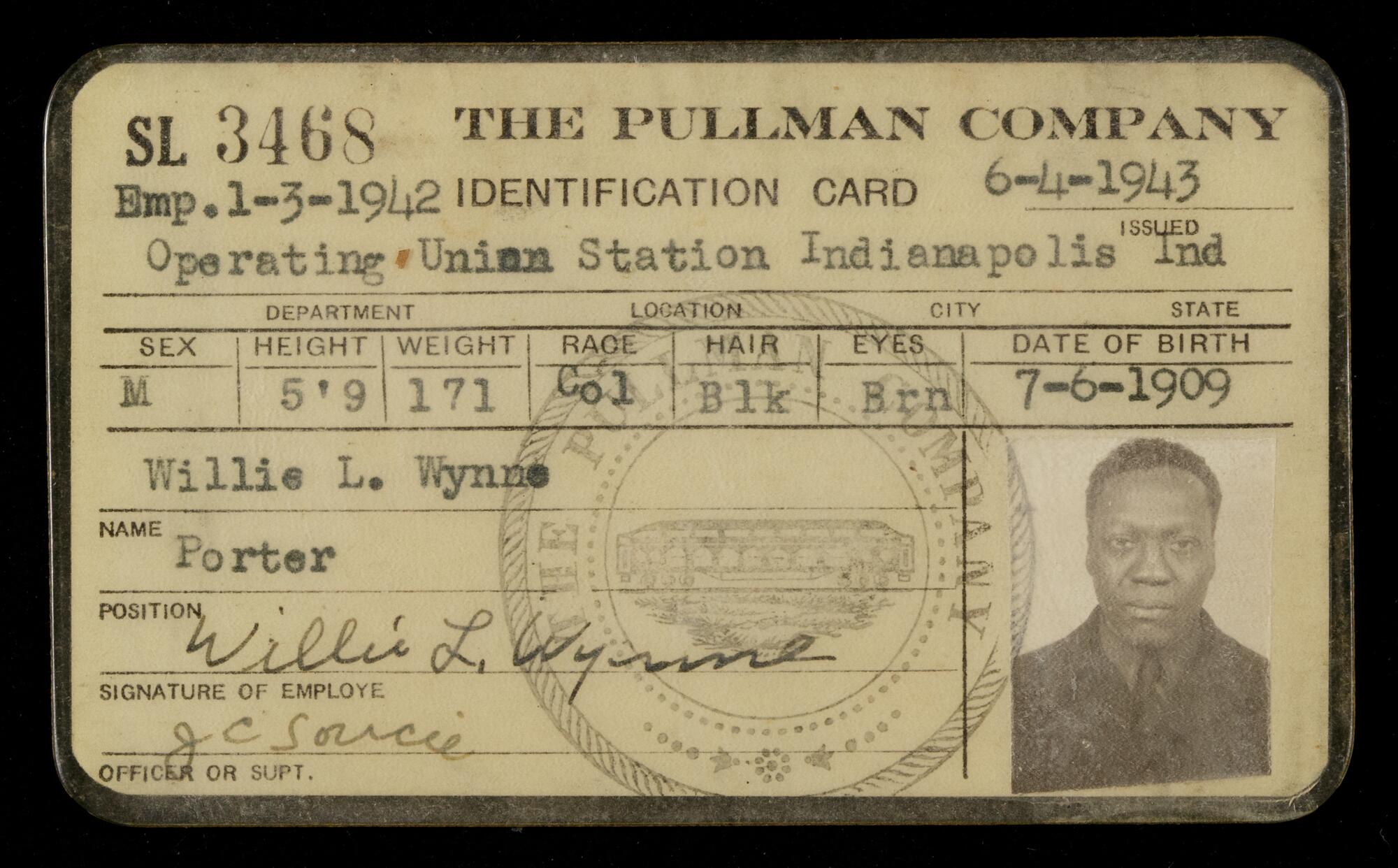

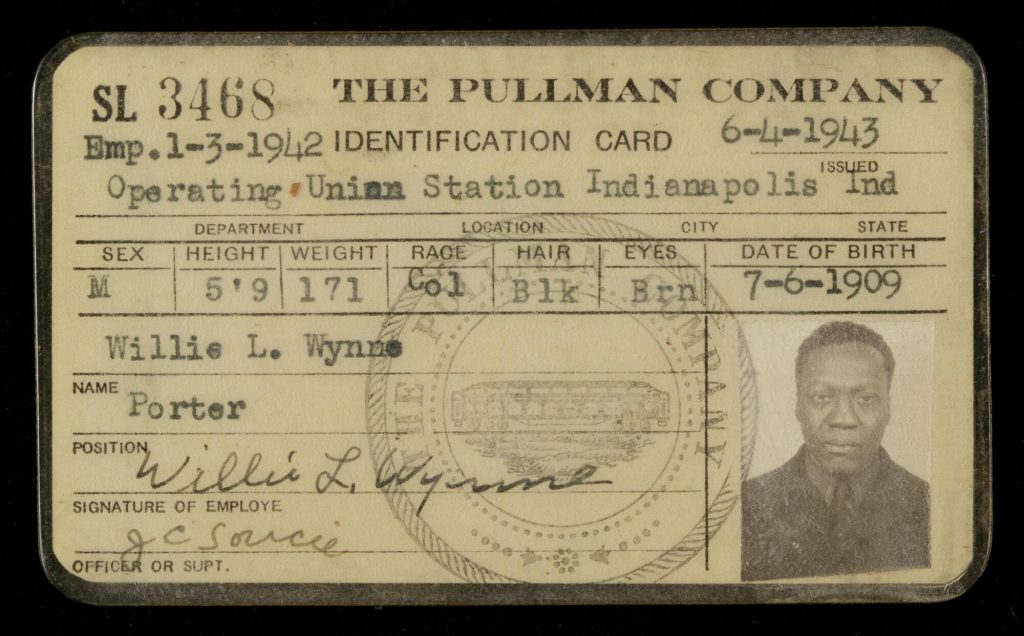

African Americans’ expanding political consciousness directly correlated to Black wartime experiences in the 1940s. Drawn to World War II’s patriotic fervor, African Americans leveraged the conflict to press for a “double victory” against fascism abroad and racial apartheid at home. In 1941, for example, A. Philip Randolph, head of the Chicago-based Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), challenged discriminatory hiring practices in the defense industries by threatening to “march on Washington.” Consequently, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which established the Fair Employment Practices Committee (albeit with dubious enforcement power). Previously having stated his opposition to “social equality,” President Harry S. Truman’s decision to sign Executive Order 9981, which desegregated the Armed Forces, was the direct result of campaigns initiated by Black industrial laborers.

Now concentrated in cities, African Americans helped transform the two-party political system. As city-dwellers, they represented a sizable constituency for both parties, which elevated their importance as voters. Prior to the 1930s, many African Americans remained tied to the Republican Party because of the party’s Reconstruction-era liberalism. The Great Depression influenced their political realignment towards the Democratic Party, however. Under Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s leadership, the Democratic Party prioritized economic relief and labor rights, but many of the New Deal’s signature programs excluded African Americans, including Social Security. Additionally, during the 1930s and 1940s, the Democratic Party remained tethered to its racist moorings, as white political officials frequently caved to the interests of segregationists who refused to adopt civil rights as part of their political platform. Nevertheless, the appointment of Mary McCleod Bethune, Robert Weaver, and other African Americans to Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet” influenced the party’s Black adherents. This new Democratic constituency was determined to exercise its expanding political power, which, in subsequent years, facilitated African Americans’ elections as local and statewide officeholders.

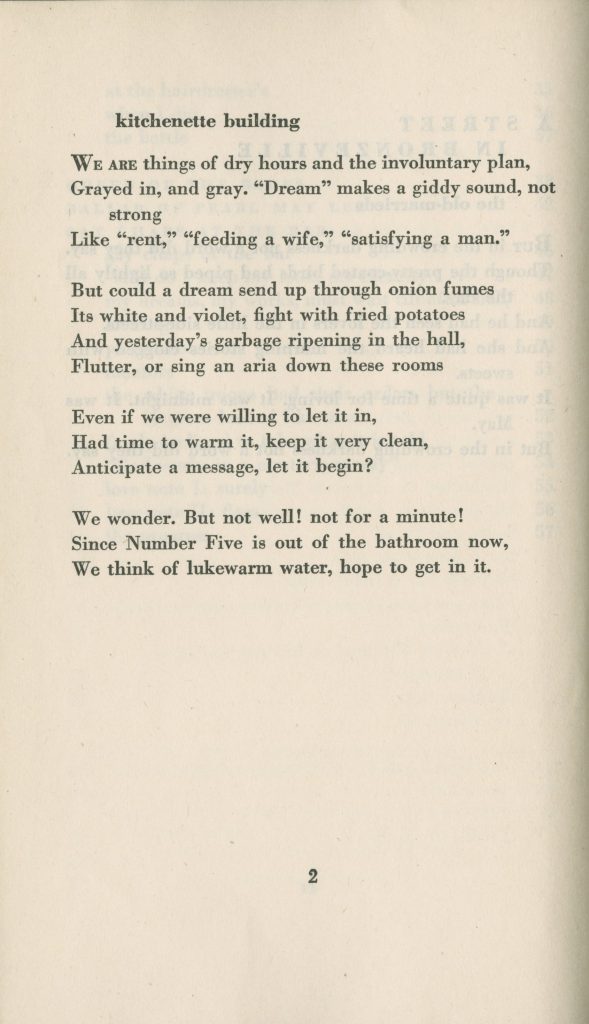

In addition to these important political transformations, African Americans also deployed their cultural capital to dramatically transform cities. For example, during the Harlem Renaissance, novelists, poets, jazz musicians, and visual artists altered New York City’s cultural landscape, and, invariably, the nation at large. Artists included Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Zora Neale Hurston, Countee Cullen, as well as the “father of the New Negro Movement” Alain Locke; “the midwife of the Renaissance” Jesse Redmond Fauset; and artist Jacob Lawrence, who painted “The Migration Series” as a way of capturing Black urban experiences. Notably, the Renaissance expanded beyond Harlem, as Davarian L. Baldwin observes, and included Chicago and various other cities. For example, the novelist Richard Wright, the playwright Lorraine Hansberry, and the poet Gwendolyn Brooks each left an indelible impact on Chicago’s literary scene. Numerous foreign-born Blacks also contributed to the cultural innovations of the early twentieth century by introducing diverse languages, religions, and art forms to America’s cities.

Questions to Consider:

- Describe Black migrant experiences upon relocation to northern and western cities, including employment and community life.

- How did the Great Migration shape Black political and cultural experiences?

“Up South”

The Great Migration’s cultural, economic, and political transformations were mutually transformative for African Americans and their new neighbors. However, the battle against economic exploitation and racial exclusion by no means ceased upon one’s arrival in the city. Early on, migrants confronted discriminatory practices that approximated their experiences in the South. Concentrated in lower rungs of employment, for example, African Americans faced limited opportunities for advancement. As “the last hired, and the first fired” from even the most menial jobs, they also faced hostility from white workers, unions, and employers.

Adequate and affordable housing also remained a sticking point for many Black families. In densely-packed urban centers such as New York, Detroit, and Oakland, African Americans discovered high rents, low-quality accommodations, and racial exclusion. Chicago’s Black housing market was especially notorious. Entire families crammed into “kitchenettes” that limited their mobility. Kitchenettes were one-room apartments that frequently combined the kitchen, dining room, and bedroom all in one space. Many kitchenettes lacked water and heat. Others relied upon wood-burning stoves and kerosene lamps to cook and to warm living quarters. In many cities, African Americans packed into single-family homes and apartments that lodged multiple families. Those unable to locate shelter in houses or apartments frequently resorted to living in churches, old warehouses, tents, and alleyways. Dangerous and unsanitary living conditions provided the basis for “inner city ghettos” and conflated images of Blacks with the problems of slum-dwelling, including disease, crime, and urban decay. A Jackson, Mississippi migrant who landed in Chicago in 1927, Richard Wright captures much of Black Chicago’s reality in his classic novel 1940 Native Son. For example, in his introductory chapter, Wright describes the various challenges faced by a family of four:

“A brown-skinned girl in a cotton gown got up and stretched her arms above her head and yawned. The two boys kept their faces averted while their mother and sister put on enough clothes to keep them from feeling ashamed; and the mother and sister did the same while the boy dressed. Abruptly, they all paused, holding their clothes in their hands, their attention caught by a light tapping in the thinly plastered walls of the room. They forgot their conspiracy against shame,” Wright continues, while subsequently describing the family’s reaction to a large rat that darts across the floor.

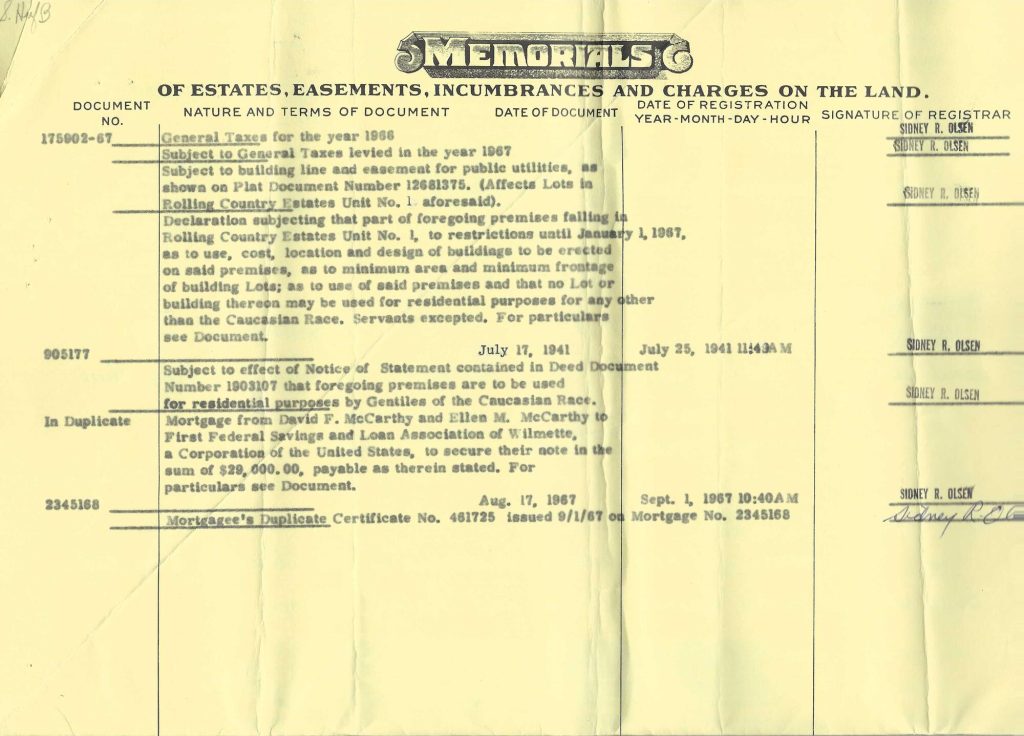

Discriminatory housing practices ensured enduring cycles of poverty. African Americans’ exclusion from entitlement programs, such as Social Security and the GI Bill, denied them home-buying assistance and exacerbated racial inequalities. In addition to the federal government’s “de facto” practices, private enterprises sanctioned discrimination. In many cities, white homeowners relied upon “restrictive covenants” to maintain the racial character of their neighborhoods. Despite the Supreme Court’s decision to outlaw restrictive covenants in Shelly v. Kraemer (1948), Black city-dwellers discovered themselves at the mercy of redlining. Consequently, banks refused to lend money to African Americans, while real estate agents directed them away from white neighborhoods. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor argues, such exploitative practices characterized Black experiences for decades to come. Meanwhile, the threat of a “black invasion” in predominantly white communities also expedited the pace of “white flight.” Segregationists sought refuge in the outlying suburbs, effectively siphoning off their tax dollars and other resources from cities, which led to the under-evaluation of urban space.

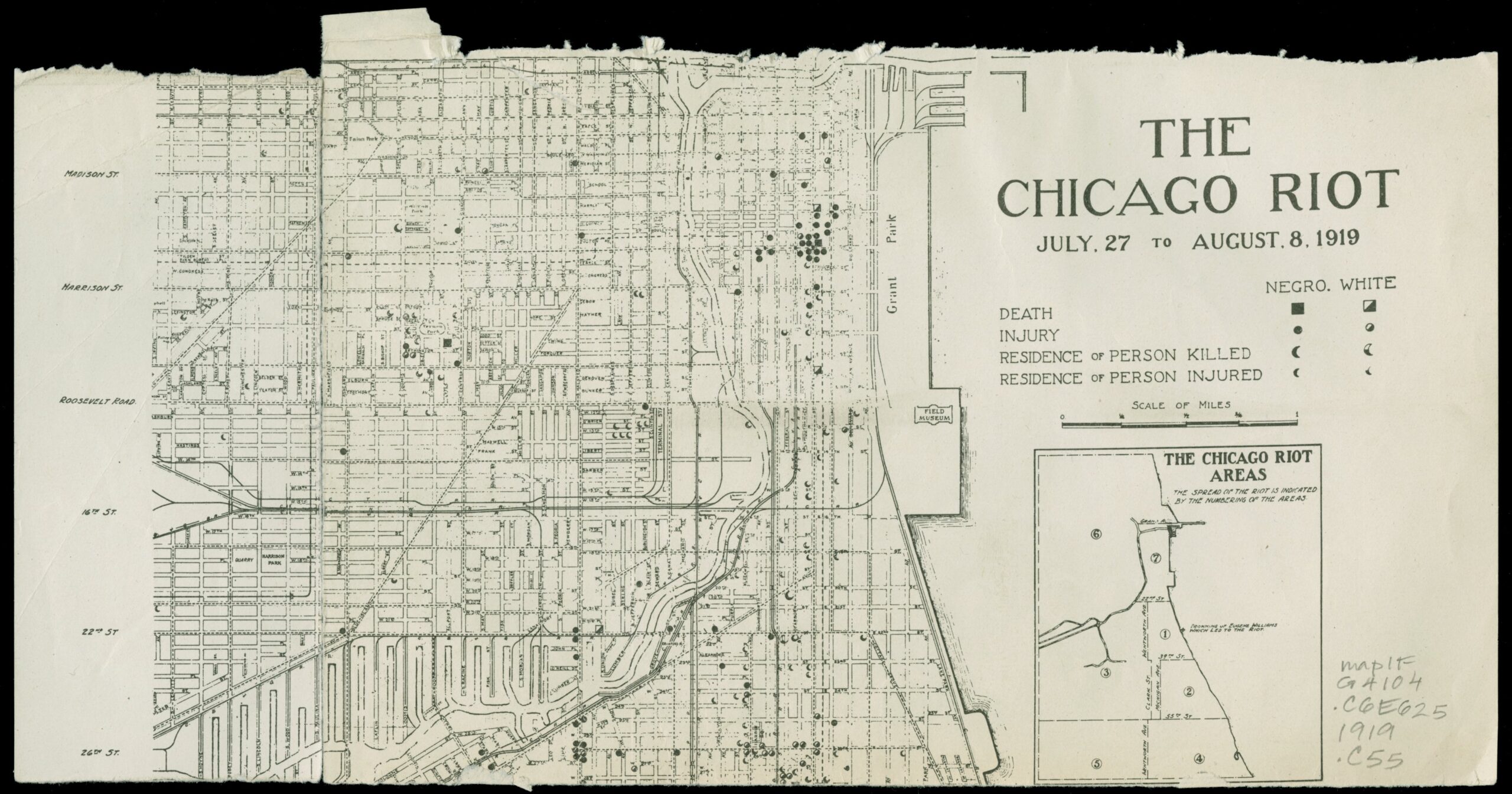

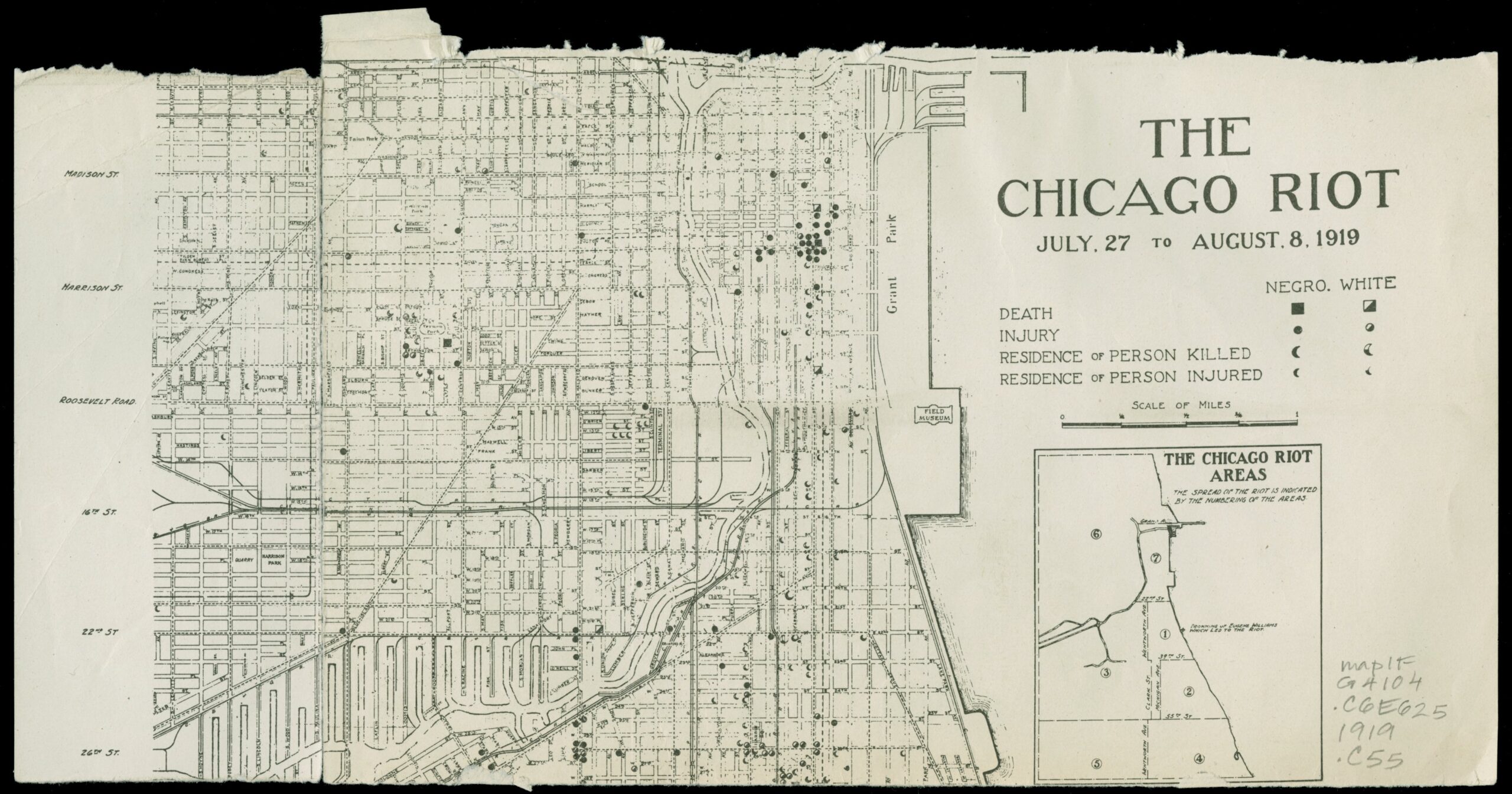

In northern cities, the escalation of violence represented the clearest response to these demographic transformations. In 1919, during what became known as “Red Summer,” a seemingly endless number of interracial conflagrations accompanied the migration waves in cities across the country, including Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. In 1943, Detroit erupted in violent confrontations between whites, who attempted to block movement into their neighborhoods, and Blacks who willingly fought back. The Detroit Riot also called attention to heightened levels of police brutality, since majority of the African Americans who died during the riot were killed at the hands of the police.

As African Americans continued to populate cities, the once seemingly progressive outlook that northern whites demonstrated towards Black education also began to dissipate. Calls for civil rights and racial equality were replaced by calls for “school choice” among white residents unable to afford relocation to the suburbs or the “segregation academies” that emerged in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, according to Noliwe Rooks. During the 1970s, Boston’s anti-bussing protests served as helpful reminders of the city’s structural patterns of racism, as well as the more overt forms that endured. So too did patterns of educational “resegregation” in Chicago, Los Angeles, and other cities during the 1980s and 90s.

Questions to Consider:

- What type of challenges did African Americans face in their new urban environments? How did these challenges compare to their previous experiences in the South?

- Overall, do you think African American gains during the Great Migration outweighed the challenges?

Legacies

The Great Migration resulted in the relocation of between five and six million Black Southerners between 1910-1970. The political, economic, and cultural changes that resulted from the Great Migration forever transformed race relations in the United States. African Americans departed the South in search of educational and economic opportunity. Their arrival in northern and western cities was met with both opportunity and hardship. They discovered that much of what was true about the South was also true about the North: “To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships,” as W.E.B. Du Bois once asserted.

Nevertheless, African Americans creatively confronted the challenges that emerged during the migration waves, and their efforts laid the groundwork for future civil rights activism. For example, African Americans’ increasing politicization during World War I and World War II provided the basis upon which they articulated their demands during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Their activism resulted in the passage of federal-level legislation designed to protect the constitutional rights of all individuals, regardless of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, and later, sexual orientation and gender identity. Black demands for economic opportunity during the first half of the twentieth century also echoed in significant ways into the 1950s and 1960s through activism that emphasized how African Americans might weaponize their dollars to demand jobs, demand entry into segregated establishments, and insist upon their full consideration as consumers. The various arts campaigns that migrants ignited also established the basis for the “Black is beautiful” campaigns of the 1960s and 1970s. Similar to the Black arts renaissance that occurred in the 1920s, these arts campaigns demonstrated the full extent of Black cultural capital in the United States, as well as their powerful influence on diverse groups of Americans. With a noticeable presence at every corner of the map, African Americans who spearheaded the Great Migration effectively transformed the national landscape, adding more color, more innovation, more political debate and awareness, and more opportunities for our country to live up to its founding principles.

Questions to Consider:

- Describe the immediate and long-term impact of the Great Migration.

- What, in your opinion, were the Great Migration’s most enduring legacies?

Please see the Further Reading tab for a list of works consulted in this essay.

About the Author

Tikia K. Hamilton currently teaches in the Department of History at Loyola University Chicago. She completed her doctorate in history at Princeton University and holds a Masters in African American Studies from Columbia University. She also attended Dartmouth College, where she majored in history. A former high school teacher, she is a recipient of the National Association of Education’s Spencer Fellowship and numerous other awards. Her forthcoming book, Making A Model System: The Battle for Educational Equality in the Nation’s Capital Before Brown chronicles the efforts of African Americans to secure equal resources under segregation and their essential pivot towards integration. The book is under contract with the University of Chicago Press. Hamilton was previously a Newberry Scholar-in-Residence and has served as panelist and workshop facilitator for various Newberry programs.

Images of Black Life in the 1920s

These images come from a set of glass slides that offer a rare look into the lives that Black migrants to Northern cities created for themselves. They were produced by the Methodist Episcopal Church in partnership with leading Black churches in Chicago. The churches probably created the slides to use in presentations raising funds to help migrants moving North. Learn more here and view them all here.

Chicago during the Great Migration

These sources reflect some of the many experiences of Black migrants who came to Chicago: substandard housing, a flourishing of art and literature, industrial labor, and racism in forms like housing discrimination and violence.

Further Reading

Adero, Malaika, Up South: Stories, Studies, and Letters of African American Migrations (The New Press, 1994).

Baldwin, Davarian, Chicago’s New Negroes: Modernity, the Great Migration, and Black Urban Life (The University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

Bates, Beth Tompkins, Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America, 1925-1945 (The University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

Best, Wallace D., Passionately Human, No Less Divine: Religion and Culture in Black Chicago, 1915-1952 (Princeton University Press, 2005).

Chatelain, Marcia, Growing Up in The Great Migration (Duke University Press, 2015).

Grossman, James, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and The Great Migration (University of Chicago Press, 1989).

Haley, Sarah, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (The University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Hine, Darlene Clar, “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West.” Signs 14, no. 4 (1989): 913.

Lasch-Quinn, Elisabeth, Black Neighbors: Race and Limits of Reform in the American Settlement House Movement, 1890-1945 (The University of North Carolina Press, 1993).

Marks, Carole, Farewell: We’re Good and Gone: The Black Migration (Indiana University Press, 1989).

Murch, Donna J., Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (The University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Painter, Nell Irvin, Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction (WW Norton and Company, 1977).

Rooks, Noliwe, Cutting School: The Segrenomics of American Education (The New Press, 2020).

Sanders, Crystal R. , A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners, Segregation Scholarships, and the Debt Owed to Public HBCUS (The University of North Carolina Press, 2024).

Taylor, Keeanga-Yahmatta, Race for Profit: Howe Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (The University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

Tolnay, Stewart E., “The African American ‘Great Migration’ and Beyond,” Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 29 (2003), pp. 209-232.

Tolnay, Stewart E. and E. M. Beck, “Black Flight: Lethal Violence and the Great Migration, 1900-1930,” Social Science History, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1990), pp.347-370.

Trotter, Joe William, The Great Migration in Historical Perspective: New Dimensions of Race, Class, and Gender (Indiana University Press, 1991).

Tushnet, Mark, The NAACP’s Legal Strategy Against Segregated Education (The University of North Carolian Press, 2005).

Watkins-Owens, Irma: Caribbean Immigrants and the Harlem Community, 1900-1930 (Indiana University Press, 1996).

Weiss, Nancy J., Farewell to the Party of Lincoln: Black Politics in the Age of FDR (Princeton University Press, 1983).

Williams, Heather Andrea, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (The University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

Wolcott, Victoria, Remaking Respectability: African American Women in Interwar Detroit (The University of North Carolina Press, 2001).