This lesson is part of a set of materials about the Great Migration. See the Related Resources tab for the rest!

Themes

African American History

Chicago History

Civil Rights

Periods

Progressive Era

Great Migration

Skills & Document Types

Close Reading

Newspapers

Black Historical Consciousness Principles[1]: Black Joy, Black Identities

Materials – Available for Download in the Downloads Tab

- Articles from the Chicago Defender

- Student source recording sheet and Defender Junior submission sheet

In this lesson, you and your students will engage with primary sources including the Chicago Defender in to explore the experiences of Black children and youth during the Great Migration. By the end of this lesson, students will apply their learning by creating their own newspaper submission.

This lesson is designed to accommodate a variety of learning styles, and is structured to include whole group instruction and discussions, small group activities, and individual application of the learned concepts. This lesson plan can be adapted to meet the needs of your individual class context.

Process

Activity 1 (Opening): Imagining Childhood in the Past

Use the following questions as a Do Now/Opening Activity to help students begin brainstorming about the importance of spaces that are shaped by and for young people themselves.

- Where are the spaces in your life where you go to interact with, learn from, and express yourself with other young people? Why are these spaces important?

- Imagine you are a young person growing up 100 years ago. How might your answer change? Where / how do you think youth connected with each other in the past?

Guided Instruction: Historical Context

Refer to the Background section provided below to offer a critical context for the students before they engage in the following sources. You are encouraged to utilize a slide deck or another visual aid to support in this section.

Activity 2 (Exploration of Sources): Read the Room

For this activity, students will be encouraged to move around the room and engage with the sources by topic. The sources are predominantly newspaper articles and content from the Defender Junior section and Bud Billiken Club.

You will need to print and display the sources in their respective groups on the wall or on the tables around the room to create stations. Display the following stations (with sources) around the room as you see fit:

- Station A: Black Culture/History

- Station B: Black Internationalism

- Station C: Daily Life/Perspectives

- Station D: Social Organization/Outreach

- Station E: Youth Connections/Impact

Students will walk around the room to different stations with a recording sheet. On the recording sheet, they will be tasked with choosing 1-2 sources from each station to interact with. They will respond to the questions for each station using the recording sheet. Students will repeat this task by rotating around the room until they have covered each station.

Activity 3 (Discussion): Whole Group Share Out

Bring students back together for a whole group discussion. Students are encouraged to use their reflection sheets to support their thinking.

Discussion questions:

- Why do you think spaces dedicated to Black culture and history were important for Black youth during this time? Are they still important now?

- What do the different perspectives in these sources tell us about Black childhood during the Great Migration era?

- What was the impact of having nationwide organizations like the Defender Jr. and Bud Billiken Club, run for and by Black youth?

Activity 4 (Assessment): Defender Junior Submission

As a culminating task, students will be asked to create their own issue of the Defender Junior (see handouts section). Provide the following prompt:

Imagine you are a child in Chicago during the Great Migration and want to submit a piece for the Defender Junior. Please choose from the following options and create your submission on the handout:

- Column: Imagine that you are a guest columnist for the Defender Jr., write a short piece giving young people advice on a topic of your choosing

- Poem: Write a poem about an aspect of childhood during this period that interested you

- Short story: Write a short fictional story about daily life as a child in the Great Migration

- Letter to the editor: Write a letter to Bud Billiken asking for advice on a topic of your choosing

Background

The Great Migration, the movement of African Americans from the south to the urban north during the early and mid-20th century marked an important time of demographic and cultural transformation for the city of Chicago. The arrival of Black migrants spurred an explosion of art, creativity and activism.

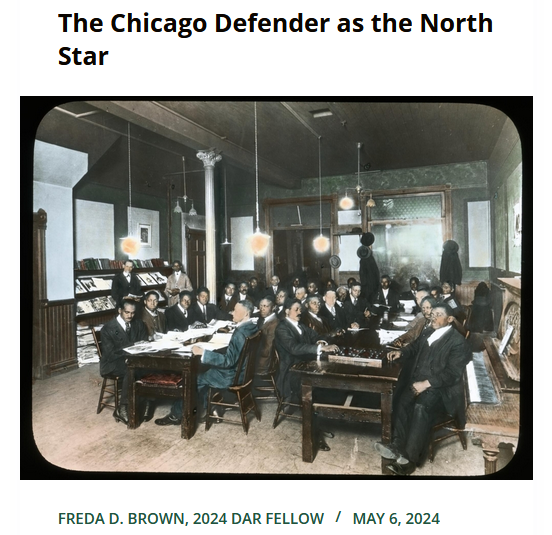

One example of this growth was the rise of the Chicago Defender, a nationally prominent Black-owned newspaper, begun in 1905. The mission of the Defender, as its name suggested, was to both shape and spread Black culture. The paperbecame a space where Black voices and concerns were celebrated and acknowledged. The Defender built critical consciousness by spreading knowledge about social and political activism. At its height, the paper reached hundreds of thousands of readers and became a fixture in Black homes across the country.

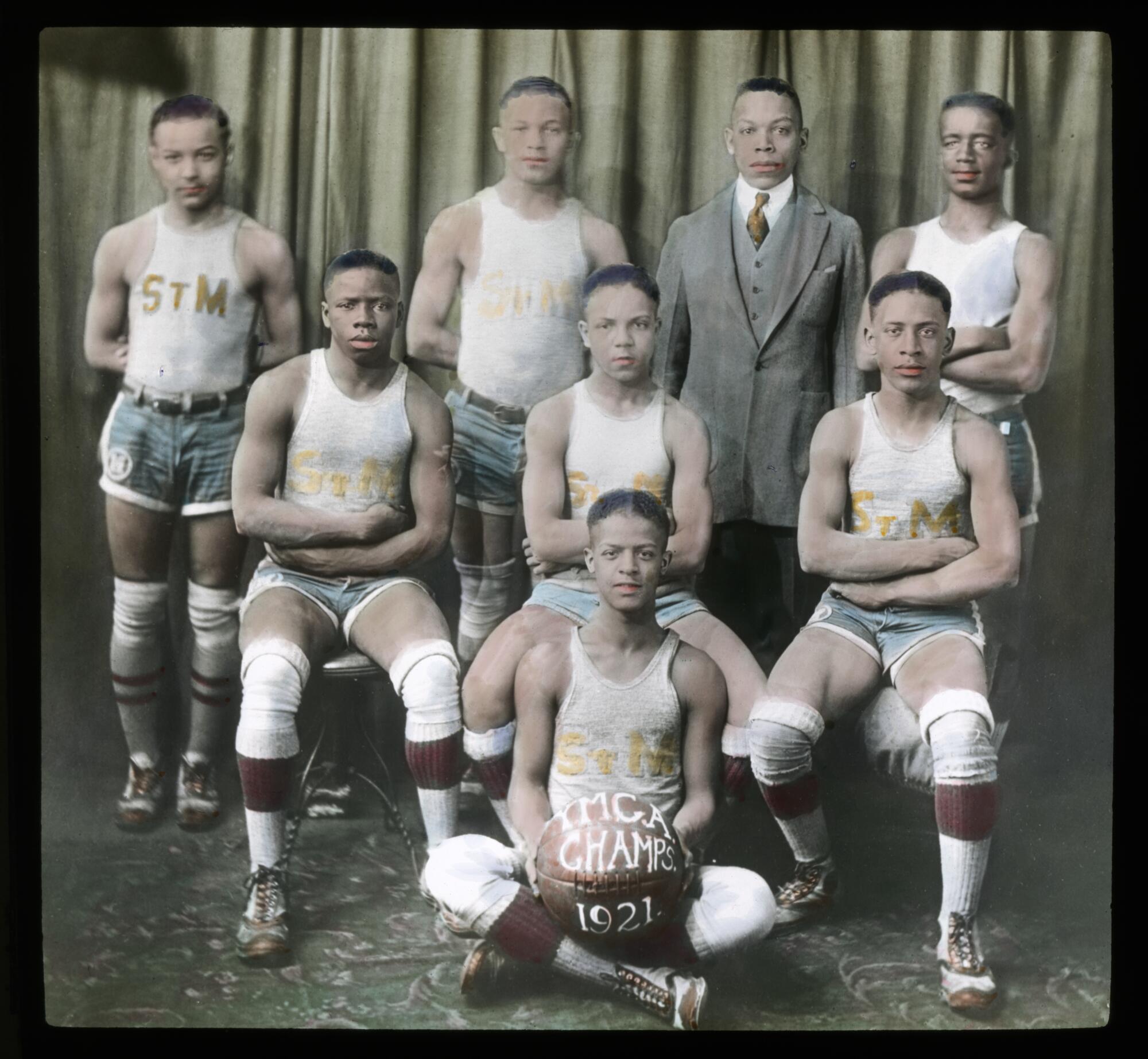

As the Defender’s cultural imprint grew, the need to engage youth in the conversations taking place in its pages became apparent. Originally the Defender had no comics, features, or other designated content for young people. To fill this void, the paper created the Defender Jr. in 1921, a section which provided the opportunity for Black youth to share their truths and talents. It quickly became “a special space for young African-Americans to learn about and engage with other children, as well as…[a space] for publishing letters, essays, stories, and poetry”.[2] The most notable component of the Defender Jr. was a column created and written by a 10-year old Black boy named Willard Motley, who took on the pen name Bud Billiken.

Motley, a shy young newspaper boy, was selected by editor Lucius Harper and publisher Robert Abbott to be the face of the Defender Jr. section. Through his charm and wit, Motley, writing as Bud Billiken, became a household name for thousands of Black children. Motley wrote directly to his fellow young readers, encouraging them to share their stories, express their creativity, and get involved in a larger community. He helped lead the Bud Billiken Club, which required highly organized efforts, such as advertising, registrations, and charters, and young people involved in leadership and outreach were compensated for their labor. Black youth around the nation, and even abroad, contributed to the club by sending in poetry and stories. They also used the Bud Billiken Club to make connections by writing to fellow members in distant cities and towns, sharing experiences and learning directly from one another. The Bud Billiken Club became incredibly popular, helping contribute to the economic success of the paper.

The Defender Jr. and the Bud Billiken Club offered spaces for Black youth to express themselves and build community. They helped young people reshape Black youth culture by defining what Black childhood meant to them. Though the column is no longer in circulation, the ripples of its impact can still be felt today through the Bud Billiken Day Parade, begun in 1929, which continues to the present.

Additional background can be referenced in The 1919 Race Riots and Race, Respectability, and Resilience: African Americans in the Midwest.

Extension Activity

Brownies’ Books

In 1920, a year before the Chicago Defender began its children’s section, another literary space devoted to Black youth printed its first issue. The Brownies’ Book, a monthly magazine produced by the NAACP’s Crisis and edited by W.E.B. Du Bois and Jessie Redmon Fauset, was dedicated to the “children of the sun” and included news articles, poems, stories, and artwork, written for (and often by) Black children and youth. As an extension, ask students to spend time with an issue of the Brownies’ Book, which is available here through the Library of Congress. Students can compare and contrast the approaches taken by these two publications to the work of uplifting and inspiring Black youth.

As a further extension, students might also look at the recently published book The New Brownies’ Book: A Love Letter to Black Families written by contemporary sociologist Karida Brown and fine artist Charly Palmer. Possible topics of conversation might include whether or not publications like the Defender Junior and Brownies’ Book are still relevant and necessary for Black youth, how these spaces might look in the age of social media, and how students themselves would design a new publication by and for young readers.

Vocabulary

Billiken | a good luck charm doll that symbolizes happiness, good fortune and positivity that became popular in the 20th century

Branch | a smaller division within a larger organization

Charter | a formal document that grants specific rights for an organization

Correspondence | refers to the exchange of written forms of communications

Jurisdiction | official power to make decisions

Mulatto | a term that describes a person with both Black and white ancestry

Porter | someone employed to carry luggage and other belongings for customers

Race-man/woman | an early twentieth century term for someone who strongly identifies with their African American heritage.

W.B | shorthand for “waste basket”

About the Authors

Michael Hines (PhD): Michael Hines is an assistant professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. His work concentrates on the educational activism of Black teachers, students, and communities during the Progressive Era (1890s-1940s). He is the author of A Worthy Piece of Work (Beacon Press, 2022) which details how African Americans educators early twentieth century Chicago created new curricular discourses around race and historical representation. Dr. Hines’s research has appeared in the Journal of African American History, the History of Education Quarterly, the Review of Educational Research, and the Journal of the History Childhood and Youth. He has written for popular outlets including The Washington Post, Time magazine, and Chalkbeat. Before earning his PhD at Loyola University Chicago and moving into academia, Dr. Hines was an ELA and social studies teacher in Washington, D.C. and Prince George’s County, Maryland.

Alexandrea Henry: Alexandrea Henry is a doctoral student in the Race, Inequality, and Language in Education program at Stanford Graduate School of Education. With over a decade of experience in educational equity, she spent 5 years as a public-school educator in North Philadelphia. Her research focuses on discipline and power dynamics in elementary classrooms, aiming to help educators reflect on their practices to create more liberatory learning experiences, particularly for Black youth. Alexandrea is passionate about teaching and learning Black history and encourages teachers and students to engage with it critically. She hopes that the folks who utilize these lessons find them useful to their practice and enjoy incorporating them into their classroom communities!

1. These principles were derived from Dr. LaGarrett J. King’s work, Black History is Not American History: Toward a Framework of Black Historical Consciousness (2020), where he offers a set of guiding principles to encourage teachers of history “to understand, develop, and teach Black histories that recognize Black people’s humanity” (p. 337). The authors of this lesson plan utilized these principles to frame our work and encourage educators and students to engage with these principles as well. [return]

2. Gray, P. “Join the Club: African American Children’s Literature, Social Change, and the Chicago Defender Junior” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly (42)2, 2017. p149-168. [return]

This lesson supports the following Illinois State Board of Education Social Science Standards:

Priority Standards: SS.CV.3.6-8.LC, MdC, MC: Compare the means by which individuals and groups change societies, promote the common good, and protect rights.

Evaluating Sources & Using Evidence: SS.IS.4.6-8.MC. Gather relevant information from credible sources and determine whether they support each other.

Developing Claims and using evidence: SS.IS.5.6-8.MdC.Identify evidence from multiple sources to support claims, noting its limitations

Communicating Conclusions: SS.IS.6.6-8LC. Construct arguments using claims and evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging their strengths and limitations.

Download the following materials below:

- Copy of the lesson “Black Childhood and the Great Migration”

- Articles from the Chicago Defender

- Student source recording sheet and Defender Junior submission sheet