This lesson is part of a set of materials about the Great Migration. See the Related Resources tab for the rest!

Themes

African American History Chicago History

Labor History

Women’s History

Periods

Progressive Era

Great Migration

Skills & Document Types

Visual Literacies

Close Reading

Charts & Graphs

Black Historical Consciousness Principles[1]: Power & Oppression, Black Agency, Resistance & Perseverance, Black Identities

Materials – Available for Download in the Downloads tab

- The poem “The Great Migration” (high-resolution version)

- “The Pullman Porter” pamphlet (high-resolution version)

- A. Philip Randolph letter (high-resolution version)

- Charts and interviews from The Black Metropolis (high-resolution versions)

- Source analysis and reflection handouts

- Optional: vocabulary list

Process

In this lesson, students will engage with a variety of sources, which include charts, graphs, pamphlets, and interview responses from a large study to analyze the relationship between the Great Migration and the experiences of Black workers. By the end of this lesson, students will analyze these sources to evaluate whether the north was a “Promised Land” for Black migrants.

This lesson is designed to accommodate a variety of learning styles and is structured to include whole group instruction and discussions, small group activities, and individual application of the learned concepts. This lesson plan can be adapted to meet the needs of your individual class context.

Activity 1 (Opening): “The Great Migration” Poem

Introduce the poem “The Great Migration,” by Kevin Coval, either by reading it aloud with students following along or having students read independently. As they read, students should be encouraged to annotate the text, circling, highlighting, underlining and writing notes next to words, phrases, or images that stood out to them or seemed important.

Turn and Talk: What were your first impressions of this poem? What words, phrases, or images stood out to you? What do you think is the author’s perspective about the migration and life in Chicago?

Whole Group: Invite students to share out what their groups discussed with one another, then transition into the goals for the lesson. Tell students to hold onto the parts that resonated most with them, as they will be revisiting the poem later in the lesson. Explain that today you will be looking at the relationship between the Great Migration and Black labor in Chicago.

Guided Instruction

Refer to the Background section provided below to offer a critical context for the students before they engage in the following sources. You are encouraged to utilize a slide deck or another visual aid to support in this section.

Activity 2 (Source Analysis): Charts & Anecdotes

In this portion of the lesson, students will have an opportunity to engage with primary sources related to the topic. The goal of this section is to encourage students to consider the relationship between their assigned source, and what the source reveals about the experiences of Black workers during the Great Migration.

Divide the class into three groups. Each group will be assigned a source. Give students time to explore the sources, discuss them together, and fill out their source analysis handout.

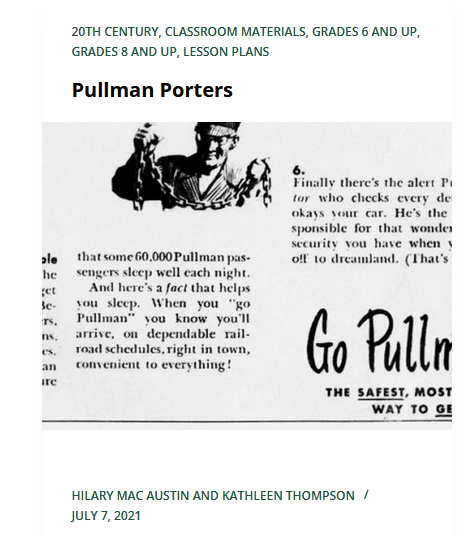

- Group 1: “The Pullman Porter” pamphlet

- Group 2: Interviews with domestic workers from The Black Metropolis

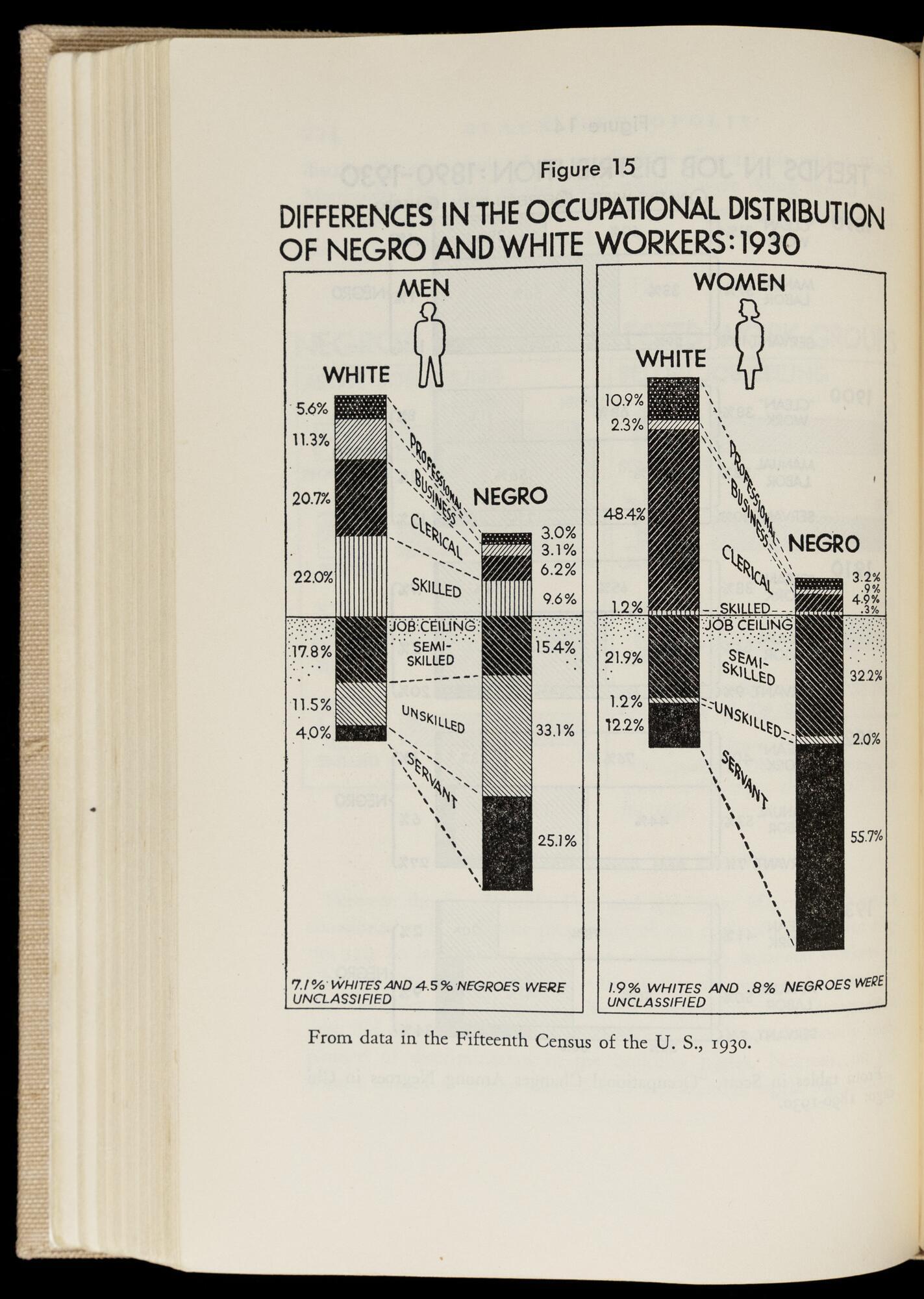

- Group 3: Labor charts from The Black Metropolis

Activity 3 (Discussion): Whole Group Share Out

Bring students back together for a whole group discussion. Have each group introduce their sources by having them share a summary of their source. Once every group has shared, use the questions below to engage in a whole group discussion and record student responses on an anchor chart at the front of the room.

Discussion questions:

- What ideas do these sources have in common? What differences did you see between the sources?

- Taken together, what do these sources tell us about the experiences of Black workers in Chicago?

- Revisit the poem: How does this activity give you a new understanding of the poem?

Activity 4 (Assessment): Student Response to Poem

As a culminating task, students will be asked to revisit the last line of Kevin Coval’s poem “The Great Migration,” which reads: “Everything will change and nothing will.” Have students consider the sources and information from the lesson as they respond to the following in a journal or handout:

- What were the experiences of Black workers during the Great Migration? Did the North live up to being the “Promised Land” for Black women and men? Why or why not?

- Do you believe that Black Chicagoans today have gained the access and opportunities that migrants searched for during the Great Migration? Why or why not?

Background

The Great Migration of African Americans to the urban north during the early to mid-20th century was a time of demographic and cultural transformation for the city of Chicago. Central to the migration’s impact was the role that economic advancement and autonomy played in the motivations of Black migrants.

For many Black southerners, the North represented a “promised land”, offering the prospect of greater freedom, economic opportunity, and upward mobility. The oppressive conditions of the Jim Crow South, including racial segregation, discrimination, and economic exploitation, pushed many to seek a better life elsewhere. Northern cities like Chicago, with their industrialized economies and potentially more progressive racial attitudes, held the promise of a brighter future.

Although Black migrants often found better opportunities in Chicago than those available in the Southern cities and towns they left behind, life in the North presented its own challenges. Racism and discrimination meant that Black workers were often still at the bottom of Chicago’s economy, forced into unskilled and low wage positions, from which they could be fired at a moment’s notice. These experiences were often defined by gender, with Black women relegated to domestic work and Black men pushed into menial labor and factory work. However, Black women and men resisted economic exploitation, and formed organizations like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first union led by African Americans, to fight for better wages and working conditions.

The intersection of the Great Depression, the Great Migration, and World War II shaped the landscape of African American life in Chicago. The economic hardships of the Great Depression served as a catalyst for migrants to move north, as many Black southerners sought better opportunities in Northern cities like Chicago. The demand for labor during World War II further accelerated this migration, as African Americans sought employment in the city’s burgeoning industries. However, these influxes also heightened racial tensions and exacerbated existing disparities, particularly in housing and employment.

To better understand the social, cultural, and economic dynamics of Black communities in Chicago, St. Clair Drake, an anthropologist, and Horace R. Cayton, a sociologist, authored The Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, in 1945. Drake and Cayton’s research gave insight into the effects of systemic racism on housing, education, and employment opportunities for Black migrants in Chicago. However, this work also illuminated the resiliency and agency of Black communities in the ways in which they confronted these challenges.

Additional Background can be found in the collection essays The Great Migration in Historical Perspective and Migration and the Midwest.

Extension Activities

Migration and Poetry

Have students write a poem in the style of Kein Coval, centering their own lived experiences with migration, whether in their personal lives, families, or broader communities.

Visual Media and Activism

Visual representations like the charts, graphs, and illustrations (like those used by St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton) were a key way that Black social scientists chose to present their findings in the early twentieth century. Have students read the short piece on the “infographic activism” of W.E.B. Dubois, which paved the way for later sociologists like Drake and Cayton. Discuss:

- How did Dubois and other Black social scientists use visual media as a tool for advancing racial justice?

- How do present day activists use aesthetics and information to help draw our attention to social and political issues?

Vocabulary

Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters | a union representing Pullman Porters, which began in 1925

Clean work | jobs in the service sector or “skilled” trades

Clerical | office duties

“The Defender” | (The Chicago Defender) a prominent Black newspaper founded in 1905 that advocated for civil rights and provided a platform for Black voices, particularly during the Great Migration

Domestic | work related to performing tasks in the home (such as childcare, cleaning, cooking, etc.)

“Job Ceiling” | the invisible barriers or limitations that prevented Black laborers from advancing to higher positions, due to discriminatory or racist workplace practices

Occupational Distribution | the arrangement of different people across different job types

Promised Land | metaphor to describe the northern cities in the US where Black southerners could migrate to for a sense of hope and better living and working conditions outside of the threat of racial oppression

Pullman Porter | employees who worked on Pullman Company railroad cars, where they assisted passengers, carried luggage, and performed other service-oriented tasks

Restrictive Covenants | legally binding agreements that impose limitations and restrictions on who can sell, buy, lease, or own a property

Semi-skilled | typically refers to workers who have acquired some basic training or experience in a particular field or occupation but may not possess the advanced skills or qualifications required for highly specialized tasks

Tenements | multi-story buildings that are divided into multiple small apartments; they are typically found in urban areas and are low-quality and overcrowded

Unskilled | refers to work that requires minimal training, education, or specialized knowledge, often involving repetitive tasks or manual labor that can be performed with little to no prior experience

White Collar | Typically refers to professional workers and administrative roles and is often associated with office work, business, finance, or other industries that require higher levels of education, specialized skills, and knowledge

About the Authors

Michael Hines (PhD): Michael Hines is an assistant professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. His work concentrates on the educational activism of Black teachers, students, and communities during the Progressive Era (1890s-1940s). He is the author of A Worthy Piece of Work (Beacon Press, 2022) which details how African Americans educators early twentieth century Chicago created new curricular discourses around race and historical representation. Dr. Hines’s research has appeared in the Journal of African American History, the History of Education Quarterly, the Review of Educational Research, and the Journal of the History Childhood and Youth. He has written for popular outlets including The Washington Post, Time magazine, and Chalkbeat. Before earning his PhD at Loyola University Chicago and moving into academia, Dr. Hines was an ELA and social studies teacher in Washington D.C. and Prince George’s County Maryland.

Alexandrea Henry: Alexandrea Henry is a doctoral student in the Race, Inequality, and Language in Education program at Stanford Graduate School of Education. With over a decade of experience in educational equity, she spent 5 years as a public-school educator in North Philadelphia. Her research focuses on discipline and power dynamics in elementary classrooms, aiming to help educators reflect on their practices to create more liberatory learning experiences, particularly for Black youth. Alexandrea is passionate about teaching and learning Black history and encourages teachers and students to engage with it critically. She hopes that the folks who utilize these lessons find them useful to their practice and enjoy incorporating them into their classroom communities!

1. These principles were derived from Dr. LaGarrett J. King’s work, Black History is Not American History: Toward a Framework of Black Historical Consciousness (2020), where he offers a set of guiding principles to encourage teachers of history “to understand, develop, and teach Black histories that recognize Black people’s humanity” (p. 337). The authors of this lesson plan utilized these principles to frame our work and encourage educators and students to engage with these principles as well. [return]

This lesson supports the following Illinois State Board of Education Social Science Standards:

Evaluating Sources and Using Evidence: SS.6-8.IS.2.M.C. Gather relevant information from credible sources and determine whether they support each other.

History: SS.6-8.H.4.MC. Organize and critique applicable evidence to develop a coherent argument about the past

Financial Literacy: SS.6-8.EC.FL.1.L.C. Analyze the relationship between skills, education, jobs, and income

Communicating Conclusions: SS.IS.6.6-8LC. Construct arguments using claims and evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging their strengths and limitations.

Download the following materials below:

- Copy of the lesson “Black Labor and the Great Migration”

- Student source analysis and reflection handout

- Sources used in this lesson

- Vocabulary list