This lesson is part of a set of materials about the Great Migration. See the Related Resources tab for the rest!

Themes

African American History

Chicago History

Chicago Renaissance

Religious History

Periods

Great Migration

Skills & Document Types

Close Reading

Government Reports

Newspapers

Photographs

Maps

Black Historical Consciousness Principles [1]: Black Agency, Resistance, & Perseverance, Black Joy, Black Identities, Black Historical Contention

Materials – Available for Download in the Downloads Tab

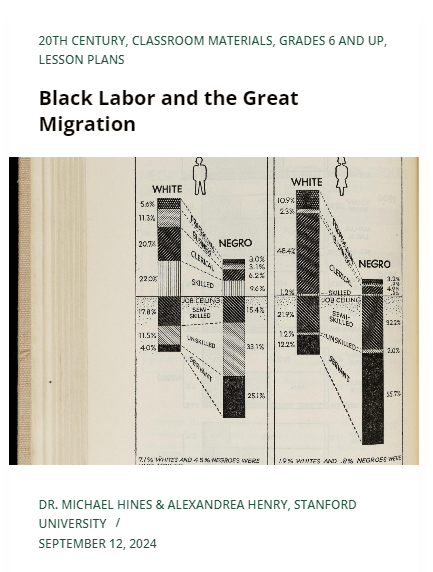

- Images from The Negro in the City (high-resolution versions)

- Excerpts and maps from The Negro in Chicago (high-resolution versions)

- Chicago Defender article

- Student handout

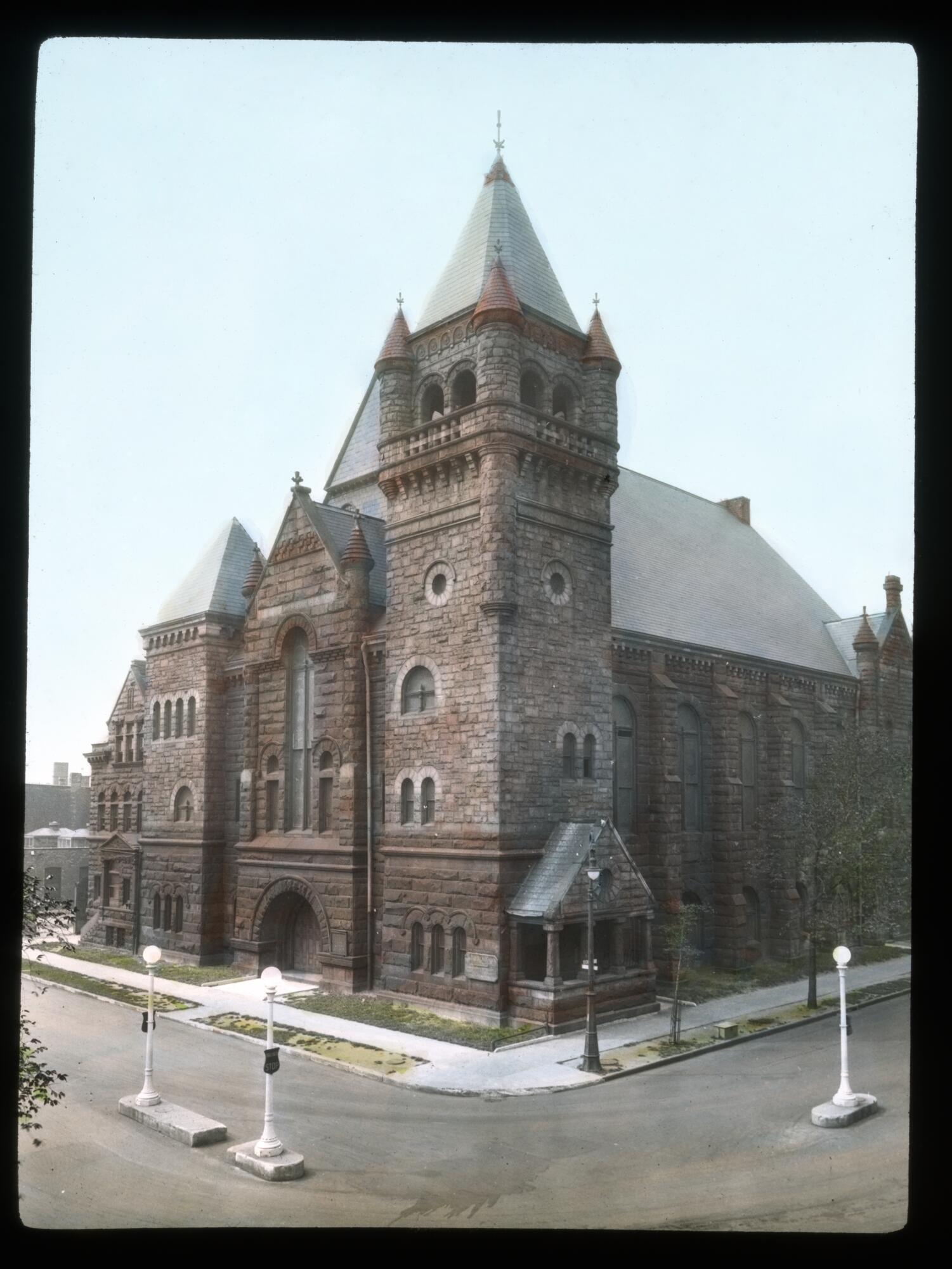

In this lesson, you and your students will engage with a variety of primary sources, including lantern slides, newspaper articles, maps, and charts, to analyze the relationship between the Black church and Chicago’s Black community during the Great Migration. By the end of the lesson, students will apply their learning to create anchor charts representing important themes and takeaways revealed through their research.

This lesson is designed to accommodate a variety of learning styles and is structured to include whole group instruction and discussions, small group activities, and individual application of the learned concepts. This lesson plan can be adapted to meet the needs of your individual class context.

Process

Activity 1 (Opening): Identifying Institutions in Your Community

Begin this lesson by having students respond to the following journal prompt:

- Take a moment to think about the multiple communities you are a part of (ex. your family, neighborhood, school, etc.). Communities often have institutions (organizations, clubs, teams, political parties, etc.) that bring people together for a common purpose or for a shared interest. Using this information as background, think about the following:

- What institutions are a central part of your community or communities? Why are these institutions valuable to the people who take part in them?

Engage students in a discussion around what makes an institution vital to a community using the following:

Turn and Talk: Have students share their reflections with their peers and have groups notice similarities and differences between responses.

Whole group discussion: Have partners share their findings, and as a class, discuss the commonalities that emerged from the share out. Document student responses on an anchor chart, whiteboard, etc. Then, use this discussion to transition to the Black church, an important institution for Black migrants during the Great Migration, which filled many of the same purposes generated from the class discussion.

Guided Instruction: Historical Contex

Refer to the Background section provided below to offer a critical context for the students before they engage in the following sources. You are encouraged to utilize a slide deck or another visual aid to support in this section.

Activity 2: Exploring the Sources

For this activity, students will break into small groups and develop expertise on one set of primary sources. Then they will form new mixed groups to share their new learning with other members of the class. Lastly, they will create a visual that integrates their learning across the sources.

Part I: Source Analysis

Assign students into three groups. Each group will be responsible for analyzing one source together with their group members.

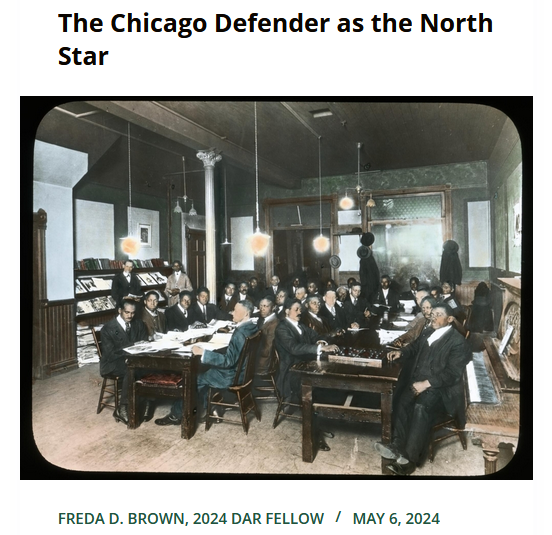

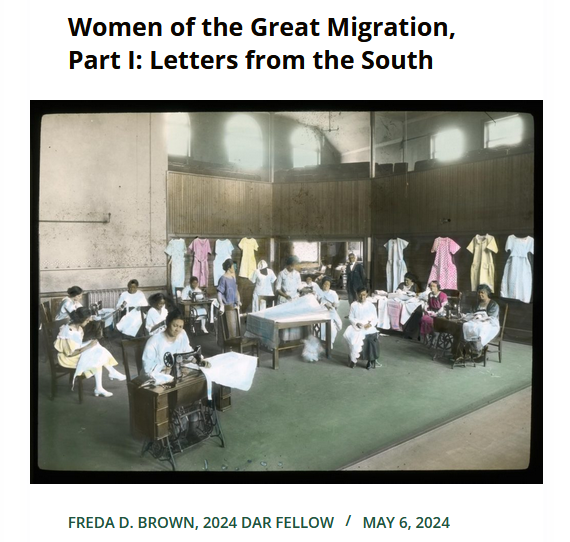

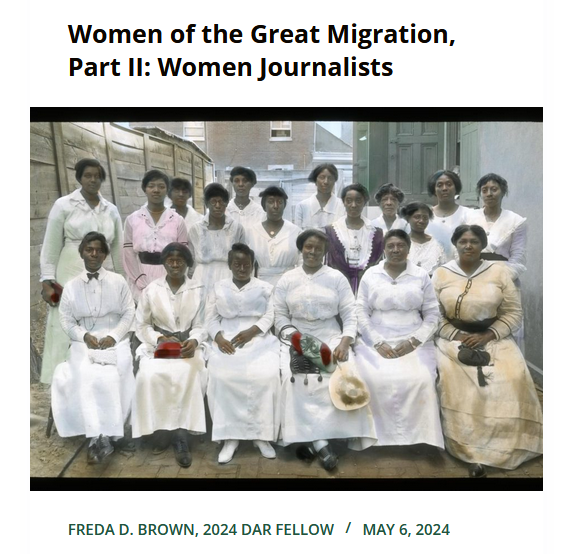

- Group 1: Lantern Slides

- Group 2: Maps and Charts

- Group 3: Newspaper article

Suggested Guiding Questions:

- What do you notice about this source? What do you wonder?

- What does this source reveal about the role of the Black church in Chicago?

- Based on this source, describe the relationship between the Black church and Black Chicagoans during the Great Migration.

Part II: Jigsaw

Next, students will form new groups with at least one representative from each of the groups from Part I so that they can bring the sources into conversation. Depending on how many students are in the class, the final groupings should consist of 3 members – one from Group 1 (lantern slides), one from Group 2 (maps and charts), and one member from Group 3 (newspaper articles).

In their newly formed groups, students will share which source they had in Part I and what they learned. After each group member has shared, students will look for connections across the different sources.

Suggested Guiding Questions:

- What role did the Black church play in each of the three sources?

- What is the relationship between the sources? Are there ideas that tie all three together?

- Based on all three sources, how would you describe the relationship between the Black church and the Black community during the Great Migration?

Part III: Visual

Lastly, students will create a visual representation of how their three sources relate to one another. This visual should include a mixture of text and images and be colorful, eye catching, and expressive.

Activity 3 (Discussion): Whole Group Share Out

Bring students back together for a whole group discussion. During this time, the small groups formed in Part II will have an opportunity to display their work to the whole class. Encourage students to consider what themes and big ideas emerge in the visuals created by each group, and to think about the major takeaways from the sources as a whole. Once everyone has had an opportunity to share their work, you will facilitate a discussion on the themes that emerged.

Discussion questions:

- What themes emerged from the presentations? Where was their overlap between presentations? Where were there independent ideas?

- What story do these sources tell about the role of Black church during the Great Migration?

- Based on your research, do you believe that Black churches were important institutions during the Great Migration? Why or Why not?

Background

The Great Migration, the movement of African Americans from the south to the urban north in the early and mid twentieth century, reshaped Chicago’s demographic and cultural landscape. Central to this transformation was the Black church— which provided a space for spiritual solace, social activism, and cultural experimentation. The Black church was a vital institution within the context of African American life, a place where African and Southern Black folk traditions met modern aesthetics and attitudes.

Black churches were vibrant hubs for social and civic engagement, leveraging their religious influence to invigorate community life. Beyond spiritual guidance, they offered social programs that supported newcomers navigating the challenges of the city. This multifaceted role positioned churches as moral and cultural guideposts, which both shaped and responded to the challenges and aspirations of their members.

Black churches were dynamic, constantly growing and reinventing themselves as the religious tastes of Southern migrants met the urban terrain of Chicago. New beliefs and practices often clashed with the older customs of established churches, leading to tension between “Old Settlers” (already established Black Chicagoans) and newcomers (southern migrants who had just arrived to the city). Class tensions, particularly regarding music and worship styles, underlined the important role of the church in shaping cultural norms and navigating social change. These struggles ultimately led some migrants to establish their own congregations, which diversified the religious landscape and expanded the styles of worship and cultural expressions within the Black church. For example, the development of gospel music—a genre which eventually moved far beyond the church to influence the wider American music scene—highlighted the church as a place of cultural innovation.

Overall, Black churches served as beacons of hope, catalysts for community building, and stages for cultural expression. Their provision of spiritual guidance, social support, and cultural leadership underscored their significant influence on the African American community and their lasting impact on Chicago’s social and cultural landscape.

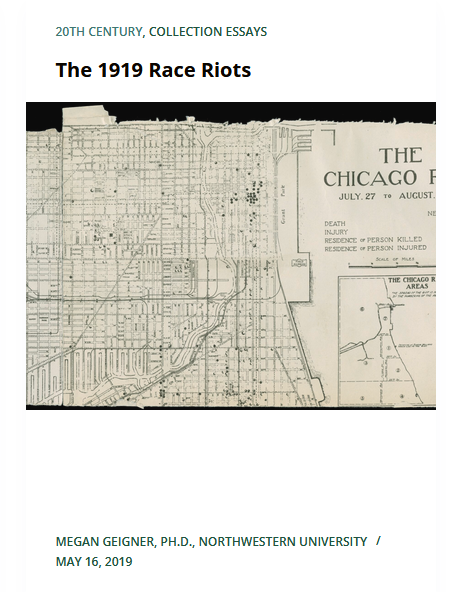

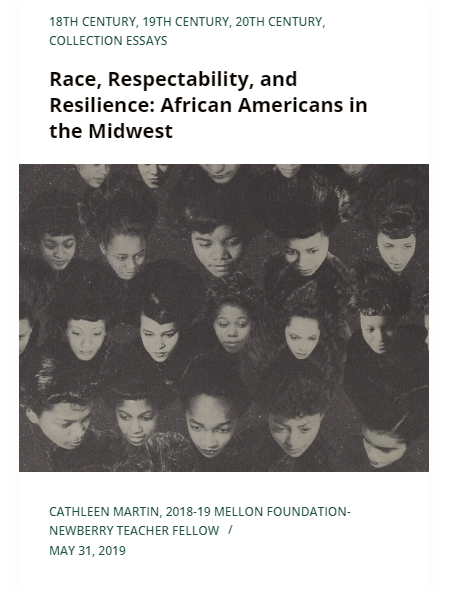

Additional background can be referenced in The 1919 Race Riots, Race, Respectability, and Resilience: African Americans in the Midwest.

Extension Activities

Migration and the Church Today

Communities of faith played a central role in supporting newcomers to Chicago during the Great Migration, providing both spiritual sustenance and material aid in the form of housing, employment, and education. Today, many faith communities in Chicago continue this legacy. Listen to “Chicago Pastor on Housing Migrants in His Church” and read the story “Mayor Brandon Johnson Announces New Church-City Partnership to House Migrants.” Discuss the similarities and differences between the role of churches in providing for migrant communities now and in the past, the challenges of relying on faith networks to provide basic services to migrant populations, and whether communities of faith are still critical institutions almost a century after the Great Migration.

The Story of Gospel Music

One of the lasting legacies of Chicago’s migration era Black churches is gospel music, a genre that started in Chicago and went on to change the trajectory of American music and culture writ large. To explore the development of gospel, have students listen to the New York Times’ 1619 Project podcast, Episode 3: The Birth of American Music and read the WTTW story The Birth of Gospel Music in Chicago. Invite students to discuss themes that emerge across these sources, including the ties between gospel and earlier forms of African and African American music, and the struggles of early gospel singers and songwriters to stay true to themselves while navigating the demands of racial respectability in the urban north.

Vocabulary

Institutions | organizations established to fulfill specific social, cultural, economic, or political purposes.

Lantern slides | transparent photographic images mounted on glass or other transparent material, used in early projection systems for educational or entertainment purposes

Storefront churches | small religious buildings or spaces typically converted from commercial storefronts, often used by independent or emerging religious congregations for worship services and community gatherings.

About the Authors

Michael Hines (PhD): Michael Hines is an assistant professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. His work concentrates on the educational activism of Black teachers, students, and communities during the Progressive Era (1890s-1940s). He is the author of A Worthy Piece of Work (Beacon Press, 2022) which details how African Americans educators early twentieth century Chicago created new curricular discourses around race and historical representation. Dr. Hines’s research has appeared in the Journal of African American History, the History of Education Quarterly, the Review of Educational Research, and the Journal of the History Childhood and Youth. He has written for popular outlets including The Washington Post, Time magazine, and Chalkbeat. Before earning his PhD at Loyola University Chicago and moving into academia, Dr. Hines was an ELA and social studies teacher in Washington, D.C. and Prince George’s County, Maryland.

Alexandrea Henry: Alexandrea Henry is a doctoral student in the Race, Inequality, and Language in Education program at Stanford Graduate School of Education. With over a decade of experience in educational equity, she spent 5 years as a public-school educator in North Philadelphia. Her research focuses on discipline and power dynamics in elementary classrooms, aiming to help educators reflect on their practices to create more liberatory learning experiences, particularly for Black youth. Alexandrea is passionate about teaching and learning Black history and encourages teachers and students to engage with it critically. She hopes that the folks who utilize these lessons find them useful to their practice and enjoy incorporating them into their classroom communities!

1. These principles were derived from Dr. LaGarrett J. King’s work, Black History is Not American History: Toward a Framework of Black Historical Consciousness (2020), where he offers a set of guiding principles to encourage teachers of history “to understand, develop, and teach Black histories that recognize Black people’s humanity” (p. 337). The authors of this lesson plan utilized these principles to frame our work and encourage educators and students to engage with these principles as well.[return]

This lesson supports the following Illinois State Board of Education Social Science Standards:

Priority Standards:

- SS.CV.3.6-8.LC, MdC, MC: Compare the means by which individuals and groups change societies, promote the common good, and protect rights.

- SS.CV.1.6-8.MC: Evaluate the powers and responsibilities of citizens, political parties, interest groups, and the media.

Evaluating Sources & Using Evidence: SS.IS.4.6-8.MC. Gather relevant information from credible sources and determine whether they support each other.

Developing Claims and Using Evidence: SS.IS.5.6-8.MdC.Identify evidence from multiple sources to support claims, noting its limitations

Communicating Conclusions: SS.IS.6.6-8LC. Construct arguments using claims and evidence from multiple sources, while acknowledging their strengths and limitations.

Download the following materials below:

- A copy of the lesson “The Black Church and the Great Migration”

- Primary source sets for each student group

- Student handout